The Winding Road to King's Reach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

An Actor's Life and Backstage Strife During WWII

Media Release For immediate release June 18, 2021 An actor’s life and backstage strife during WWII INSPIRED by memories of his years working as a dresser for actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit, Ronald Harwood’s evocative, perceptive and hilarious portrait of backstage life comes to Melville Theatre this July. Directed by Jacob Turner, The Dresser is set in England against the backdrop of World War II as a group of Shakespearean actors tour a seaside town and perform in a shabby provincial theatre. The actor-manager, known as “Sir”, struggles to cast his popular Shakespearean productions while the able-bodied men are away fighting. With his troupe beset with problems, he has become exhausted – and it’s up to his devoted dresser Norman, struggling with his own mortality, and stage manager Madge to hold things together. The Dresser scored playwright Ronald Harwood, also responsible for the screenplays Australia, Being Julia and Quartet, best play nominations at the 1982 Tony and Laurence Olivier Awards. He adapted it into a 1983 film, featuring Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay, and received five Academy Award nominations. Another adaptation, featuring Ian McKellen and Anthony Hopkins, made its debut in 2015. “The Dresser follows a performance and the backstage conversations of Sir, the last of the dying breed of English actor-managers, as he struggles through King Lear with the aid of his dresser,” Jacob said. “The action takes place in the main dressing room, wings, stage and backstage corridors of a provincial English theatre during an air raid. “At its heart, the show is a love letter to theatre and the people who sacrifice so much to make it possible.” Jacob believes The Dresser has a multitude of challenges for it to be successful. -

Dame Ellen Terry GBE

Dame Ellen Terry GBE Key Features • Born Alice Ellen Terry 27 February 1847, in Market Street, Coventry • Married George Frederic Watts, artist 20 February 1864 in Kensington. Separated 1864. Divorced 13 March 1877 • Eloped with Edward William Godwin, architect in 1868 with whom she had two children – Edith (b1869) and Edward Gordon (b1872). Godwin left Ellen in early 1875. • Married Charles Kelly, actor 21 November 1877 in Kensington. Separated 1881. Marriage ended by Kelly’s death on 17 April 1885. • Married James Carew, actor 22 March 1907 in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA. Unofficially separated 1909. • Died 21 July 1928 Smallhythe Place. Funeral service at Smallhythe church. Cremation at Golders Green Crematorium, London. Ashes placed in St Paul’s Covent Garden (the actors’ church). Urn on display on south wall (east end). A brief marital history Ellen Terry married three times and, between husbands one and two, eloped with the man who Ellen Terry’s first marriage was to the artist G F Watts. She was a week shy of 17 years old, young and exuberant, and he was a very neurotic and elderly 46. They were totally mismatched. Within a year he had sent her back to her family but would not divorce her. When she was 21, Ellen Terry eloped with the widower Edward Godwin and, as a consequence, was estranged from her family. Ellen said he was the only man she really loved. They had two illegitimate children, Edith and Edward. The relationship foundered after 6 or 7 years when they were overcome by financial problems resulting from over- expenditure on the house that Godwin had designed and built for them in Harpenden. -

January 2012 at BFI Southbank

PRESS RELEASE November 2011 11/77 January 2012 at BFI Southbank Dickens on Screen, Woody Allen & the first London Comedy Film Festival Major Seasons: x Dickens on Screen Charles Dickens (1812-1870) is undoubtedly the greatest-ever English novelist, and as a key contribution to the worldwide celebrations of his 200th birthday – co-ordinated by Film London and The Charles Dickens Museum in partnership with the BFI – BFI Southbank will launch this comprehensive three-month survey of his works adapted for film and television x Wise Cracks: The Comedies of Woody Allen Woody Allen has also made his fair share of serious films, but since this month sees BFI Southbank celebrate the highlights of his peerless career as a writer-director of comedy films; with the inclusion of both Zelig (1983) and the Oscar-winning Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) on Extended Run 30 December - 19 January x Extended Run: L’Atalante (Dir, Jean Vigo, 1934) 20 January – 29 February Funny, heart-rending, erotic, suspenseful, exhilaratingly inventive... Jean Vigo’s only full- length feature satisfies on so many levels, it’s no surprise it’s widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made Featured Events Highlights from our events calendar include: x LoCo presents: The London Comedy Film Festival 26 – 29 January LoCo joins forces with BFI Southbank to present the first London Comedy Film Festival, with features previews, classics, masterclasses and special guests in celebration of the genre x Plus previews of some of the best titles from the BFI London Film Festival: -

John Collins Production Designer

John Collins Production Designer Credits include: BRASSIC Director: Rob Quinn, George Kane Comedy Drama Series Producer: Mags Conway Featuring: Joseph Gilgun, Michelle Keegan, Damien Molony Production Co: Calamity Films / Sky1 FEEL GOOD Director: Ally Pankiw Drama Series Producer: Kelly McGolpin Featuring: Mae Martin, Charlotte Richie, Sophie Thompson Production Co: Objective Fiction / Netflix THE BAY Directors: Robert Quinn, Lee Haven-Jones Crime Thriller Series Producers: Phil Leach, Margaret Conway, Alex Lamb Featuring: Morven Christie, Matthew McNulty, Louis Greatrex Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / ITV GIRLFRIENDS Directors: Kay Mellor, Dominic Leclerc Drama Series Producer: Josh Dynevor Featuring: Miranda Richardson, Phyllis Logan, Zoe Wanamaker Production Co: Rollem Productions / ITV LOVE, LIES AND RECORDS Directors: Dominic Leclerc, Cilla Ware Drama Producer: Yvonne Francas Featuring: Ashley Jensen, Katarina Cas, Kenny Doughty Production Co: Rollem Productions / BBC One LAST TANGO IN HALIFAX Director: Juliet May Drama Series Producer: Karen Lewis Featuring: Sarah Lancashire, Nicola Walker, Derek Jacobi Production Co: Red Production Company / Sky Living PARANOID Directors: Kenny Glenaan, John Duffy Detective Drama Series Producer: Tom Sherry Featuring: Indira Varma, Robert Glennister, Dino Fetscher Production Co: Red Production Company / ITV SILENT WITNESS Directors: Stuart Svassand Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: Ceri Meryrick Featuring: Emilia Fox, Richard Lintern, David Caves Production Co: BBC One Creative Media Management -

A PSILLAS Biog Audiocraft

Sound Designer: Mr Avgoustos Psillas Avgoustos established AudioCarft Scandinavia in 2020 after 12 years at Autograph Sound in London, where he worked as a sound designer. Autograph Sound is a leading British sound design and equipment hire company, responsible for numerous theatre productions in the UK and abroad, including: Hamilton, Les Misérables, Wicked!, Mamma Mia!, Book of Mormon, Marry Poppins, Matilda, Harry Potter and the cursed child and many others. Avgoustos’ designer credits for musical theatre and theatre: The Sound of Music Stockholm Stadsteater Circus Days and Night Malmö Opera & Circus Cirkör Matilda The Musical Royal Danish Theatre Funny Girl Malmö Opera Sweeney Todd Royal Danish Opera BIG The Musical Dominion Theatre, London Blues in the Night The Kiln Theatre Matilda The Musical Malmö Opera The Ferryman St James Theatre, on Broadway, NY Kiss Me Kate Opera North, London Coliseum Pippin Malmö Opera Elf The Musical The Lowry, Manchester BIG The Musical Theatre Royal Plymouth & Bord Gais, Dublin Oliver! The Curve, Leicester AGES The Old Vic, London Pygmalion Garrick Theatre, London Strangers on a Train Gielgud Theatre, London Spamalot The Harold Pinter Theatre, London Spamalot (Remount) London Playhouse EPIDEMIC The Musical The Old Vic, London Henry V Open Air Theatre Regent’s Park Hobson’s Choice Open Air Theatre Regent’s Park Winter’s Tale Open Air Theatre Regent’s Park AudioCraft Scandinavia AB | Svanvägen 59, 611 62, Nyköping, Sweden e: [email protected] | t: +44 79 50292095 | Organisation no: 559281-2035 | VAT -

The Diary of a Hounslow Girl National Tour 2016 Marketing Resource Pack

THE DIARY OF A HOUNSLOW GIRL NATIONAL TOUR 2016 MARKETING RESOURCE PACK 1 Contents 1. About the Show 2. The Creative Team 3. Ambreen Razia, Actress and Writer 4. Press Quotes and Reviews 5. Target Audience & Selling Points 6. Show Copy 7. Social Media 8. Box Office Briefing 9. Press Release 10. Interview with Meliz Gozenler (Arc Theatre participant) 11. The Hounslow Girl Glossary 12. About Black Theatre Live 13. Tour Schedule Ambreen Razia Production Team Project Manager: Maeve O’Neill [email protected] Writer and Performer: Ambreen Razia [email protected] Tour Manager: Milan Govedarica [email protected] Publicity photographer - Talula Sheppard 2 The Diary of a Hounslow Girl The Diary of a Hounslow Girl is told through the eyes of a 16-year-old British Muslim Girl growing up in West London. From traditional Pakistani weddings to fights on the night bus this is a funny, bold, provocative play highlighting the challenges of being brought up as a young woman in a traditional Muslim family alongside the temptations and influences growing up in and around London. The Diary of a Hounslow Girl geared up to take on the world. A comic story of dreams, aspirations and coming of age. Background You've heard of an Essex Girl and even a Chelsea Girl but what is a Hounslow Girl? A Hounslow Girl has become a byword for young Muslim women who wear hooped earrings along with their headscarves, tussling with their traditional families while hustling their way in urban West London. Feisty young women grappling with traditional values, city life and fashion. -

Irving Room David Garrick (1717-1779) Nathaniel Dance-Holland (1735-1811) (After) Oil on Canvas BORGM 00609

Russell-Cotes Paintings – Irving Room Irving Room David Garrick (1717-1779) Nathaniel Dance-Holland (1735-1811) (after) Oil on canvas BORGM 00609 Landscape with a Cow by Water Joseph Jefferson (1829-1905) Oil on canvas BORGM 01151 Sir Henry Irving William Nicholson Print Irving is shown with a coat over his right arm and holding a hat in one hand. The print has been endorsed 'To My Old Friend Merton Russell Cotes from Henry Irving'. Sir Henry Irving, Study for ‘The Golden Jubilee Picture’, 1887 William Ewart Lockhard (1846-1900) Oil in canvas BORGM 01330 Russell-Cotes Paintings – Irving Room Sir Henry Irving in Various Roles, 1891 Frederick Barnard (1846-1896) Ink on paper RC1142.1 Sara Bernhardt (1824-1923), 1897 William Nicholson (1872-1949) Woodblock print on paper The image shows her wearing a long black coat/dress with a walking stick (or possibly an umbrella) in her right hand. Underneath the image in blue ink is written 'To Sir Merton Russell Cotes with the kind wishes of Sara Bernhardt'. :T8.8.2005.26 Miss Ellen Terry, Study for ‘The Golden Jubilee Picture’, 1887 William Ewart Lockhart (1846-1900) Oil on canvas BORGM 01329 Theatre Poster, 1895 A theatre poster from the Borough Theatre Stratford, dated September 6th, 1895. Sir Henry Irving played Mathias in The Bells and Corporal Brewster in A Story of Waterloo. :T23.11.2000.26 Russell-Cotes Paintings – Irving Room Henry Irving, All the World’s a Stage A print showing a profile portrait of Henry Irving entitled ‘Henry Irving with a central emblem of a globe on the frame with the wording ‘All The World’s A Stage’ :T8.8.2005.27 Casket This silver casket contains an illuminated scroll which was presented to Sir Henry Irving by his friends and admirers from Wolverhampton, in 1905. -

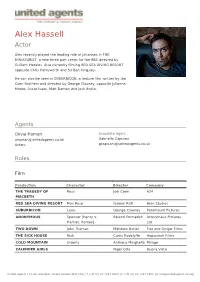

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

Transcript Sidney Lumet

TRANSCRIPT A PINEWOOD DIALOGUE WITH SIDNEY LUMET Sidney Lumet’s critically acclaimed 2007 film Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, a dark family comedy and crime drama, was the latest triumph in a remarkable career as a film director that began 50 years earlier with 12 Angry Men and includes such classics as Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network. This tribute evening included remarks by the three stars of Before the Devil Knows Your Dead, Ethan Hawke, Marissa Tomei, and Philip Seymour Hoffman, and a lively conversation with Lumet about his many collaborations with great actors and his approach to filmmaking. A Pinewood Dialogue with Sidney Lumet shooting, “I feel that there’s another film crew on moderated by Chief Curator David Schwartz the other side of town with the same script and a (October 25, 2007): different cast, and we’re trying to beat them.” (Laughter) “You know, trying to wrap the movie DAVID SCHWARTZ: (Applause) Thank you, and ahead of them. It’s like a race.” I remember welcome, everybody. Sidney Lumet, as I think all saying that “you know if this movie works, then of you know, has received a number of salutes I’m going to have to rethink my whole idea of and awards over the years that could be process, because I can not imagine that this will considered lifetime achievement awards—which work!” (Laughter) I’ve never seen such a might sometimes imply that they’re at the end of deliberate—I’m going to steal your words, Phil, their career. But that’s certainly far from the case, but—a focus of energy, and use of energy. -

Christopher Diffey – TENOR Repertoire List

Christopher Diffey – TENOR Repertoire List Leonard Bernstein Candide Role: Candide Volkstheater Rostock: Director Johanna Schall, Conductor Manfred Lehner 2016 A Quiet Place Role: François Theater Lübeck: Director Effi Méndez, Conductor Manfred Lehner 2019 Ludwig van Beethoven Fidelio Role: Jaquino Nationaltheater Mannheim 2017: Director Roger Vontoble, Conductor Alexander Soddy Georges Bizet Carmen Role: Don José (English) Garden Opera: Director Saffron van Zwanenberg 2013/2014 OperaUpClose: Director Rodula Gaitanou, April-May 2012 Role: El Remendado Scottish Opera: Conductor David Parry, 2015 (cover) Melbourne City Opera: Director Blair Edgar, Conductor Erich Fackert May 2004 Role: Dancaïro Nationaltheater Mannheim: Director Jonah Kim, Conductor Mark Rohde, 2019/20 Le Docteur Miracle Role: Sylvio/Pasquin/Dr Miracle Pop-Up Opera: March/April 2014 Benjamin Britten Peter Grimes Role: Peter Grimes (cover) Nationaltheater Mannheim: Conductor Alexander Soddy, Director Markus Dietz 2019/20 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Role: Lysander (cover) Garsington Opera: Conductor Steauart Bedford, Director Daniel Slater June-July 2010 Francesco Cavalli La Calisto Role: Pane Royal Academy Opera: Dir. John Ramster, Cond. Anthony Legge, May 2008 Gaetano Donizetti Don Pasquale Role: Ernesto (English) English Touring Opera: Director William Oldroyd, Conductor Dominic Wheeler 2010 Lucia di Lammermoor Role: Normanno Nationaltheater Mannheim 2016 Jonathan Dove Swanhunter Role: Soppy Hat/Death’s Son Opera North: Director Hannah Mulder, Conductor Justin Doyle April -

CYMBELINE" in the Fllii^Slhi TI CENTURY

"CYMBELINE" IN THE fllii^SLHi TI CENTURY Bennett Jackson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the de ree of uaster of Arts in the University of Birmingham. October 1971. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis consists of an Introduction, followed by Part I (chapters 1-2) in which nineteenth- century criticism of the play is discussed, particular attention being paid to Helen Faucit's essay on Imogen, and its relationship to her playing of the role. In Part II the stags-history of Oymbcline in London is traced from 1785 to Irving's Lyceum production of 1896. Directions from promptbooks used by G-.P. Cooke, W.C. Macready, Helen Eaucit, and Samuel ±helps are transcribed and discussed, and in the last chapter the influence of Bernard Shaw on Ellen Terry's Imogen is considered in the light of their correspondence and the actress's rehearsal copies of the play. There are three appendices: a list of performances; transcriptions of two newspaper reviews (from 1843 and 1864) and one private diary (Gordon Crosse's notes on the Lyceum Gymbeline); and discussion of one of the promptbooks prepared for Charles Kean's projected production.