Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amen De Costa-Gavras France, Allemagne, Roumanie – 2002 – 2H12

Amen de Costa-Gavras France, Allemagne, Roumanie – 2002 – 2h12 Fiche rédigée par Sandrine Weil, professeur de lettres et cinéma Alors qu'il s'agit d'un film majeur, Amen n'a semble-t-il pas suscité jusqu'alors beaucoup de présentations à des fins pédagogiques, contrairement à d'autres films. La présentation qui suit constitue une invitation à l'approfondissement de sa lecture. Avec : Ulrich Tukur, Mathieu Kassovitz, Ulrich Mühe, Marcel Iures, Ion Caramitru Scénario : Costa-Gavras, Jean-Claude Grumberg Image : Patrick Blossier Son : Pierre Gamet, Francis Wargnier Montage : Yannick Kergoat Musique : Armand Amar Un film entre le grand spectacle hollywoodien et la thèse universitaire ? Amen, est ainsi présenté sur la quatrième de couverture du DVD1: « Un officier SS et un jésuite refusent de dire ‘AMEN’ à l’horreur ». Allocine, en propose le résumé suivant : « Pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Kurt Gerstein, un officier SS allemand, épaulé par un jeune jésuite, Ricardo Fontana, tente d'informer le Pape Pie XII et les Alliés du génocide des Juifs organisé par les nazis dans les camps de concentration »2. Le film, produit par Claude Berri, a coûté cher. Il a été tourné en partie en Hongrie et en langue anglaise par des acteurs non locuteurs natifs de l’anglais. Le film se revendique aussi bien, de la part de Grumberg, co-scénariste, que de Costa Gavras comme faisant partie du « cinéma spectaculaire »3. « Il ne faut pas oublier que le cinéma, c’est du spectacle. Il ne faut pas donner au mot spectacle une connotation négative », insiste Costa Gavras qui défend ici La liste de Schindler de Spielberg : « j’ai souvenir de foules devant les cinémas. -

CBS Cuts $ on CD Front -Lines

iUI 908 (t,14 **,;t*A,<*fi,? *3- DIGIT 4401 8812 MAR90UHZ 000117973 MONTY GREENLY APT A TOP 3740 ELM 90P07 LONG BEACH CA CONCERTS & VENUES Follows page 56 VOLUME 100 NO. 13 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT March 26, 1988/$3.95 (U.S.), $5 (CAN.) 3-Inch CD Gets Big Play Dealers Get A Big Spring Break As Majors Start Ball Rolling CD Front This story was prepared by Dave said Lew Garrett, vice president of CBS Cuts $ On -lines DiMartino and Geoff Mayfield. purchasing for North Canton, Ohio- will cut prices on selected black, front -line level and will translate based Camelot Music, speaking at a BY KEN TERRY country, and new artist releases and roughly to a $1 drop in wholesale LOS ANGELES The 3 -inch compact seminar. "Now, we're more excited LOS ANGELES In a surprise MCA plans to reduce the cost of its cost. At the same time, CBS will disk got major play at the National about it." move that may have a profound ef- country CD releases (see story, start offering new and developing Assn. of Record- Discussion among many label exec- fect on industry page 71), the CBS package repre- artist product at the $12.98 list ing Merchandis- utives shifted from general concerns pricing of com- sents the most comprehensive as- equivalent, which represents a ers convention with product viability to more specific pact disks, CBS wholesale cut of about $2. NAHM here March 11 -14. matters of packaging. One executive HARM Records plans to Teller keynote, p. -

What Ever Happened to In-Yer-Face Theatre?

What Ever Happened to in-yer-face theatre? Aleks SIERZ (Theatre Critic and Visiting Research Fellow, Rose Bruford College) “I have one ambition – to write a book that will hold good for ten years afterwards.” Cyril Connolly, Enemies of Promise • Tuesday, 23 February 1999; Brixton, south London; morning. A Victorian terraced house in a road with no trees. Inside, a cloud of acrid dust rises from the ground floor. Two workmen are demolishing the wall that separates the dining room from the living room. They sweat; they curse; they sing; they laugh. The floor is covered in plaster, wooden slats, torn paper and lots of dust. Dust hangs in the air. Upstairs, Aleks is hiding from the disruption. He is sitting at his desk. His partner Lia is on a train, travelling across the city to deliver a lecture at the University of East London. Suddenly, the phone rings. It’s her. And she tells him that Sarah Kane is dead. She’s just seen the playwright’s photograph in the newspaper and read the story, straining to see over someone’s shoulder. Aleks immediately runs out, buys a newspaper, then phones playwright Mark Ravenhill, a friend of Kane’s. He gets in touch with Mel Kenyon, her agent. Yes, it’s true: Kane, who suffered from depression for much of her life, has committed suicide. She is just twenty-eight years old. Her celebrity status, her central role in the history of contemporary British theatre, is attested by the obituaries published by all the major newspapers. Aleks returns to his desk. -

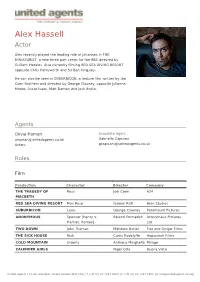

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

'Owned' Vatican Guilt for the Church's Role in the Holocaust?

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 4 (2009): Madigan CP 1-18 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING Has the Papacy ‘Owned’ Vatican Guilt for the Church’s Role in the Holocaust? Kevin Madigan Harvard Divinity School Plenary presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Council of Centers on Christian-Jewish Relations November 1, 2009, Florida State University, Boca Raton, Florida Given my reflections in this presentation, it is perhaps appropriate to begin with a confession. What I have written on the subject of the papacy and the Shoah in the past was marked by a confidence and even self-righteousness that I now find embarrassing and even appalling. (Incidentally, this observation about self-righteousness would apply all the more, I am afraid, to those defenders of the wartime pope.) In any case, I will try and smother those unfortunate qualities in my presentation. Let me hasten to underline that, by and large, I do not wish to retract conclusions I have reached, which, in preparation for this presentation, have not essentially changed. But I have come to perceive much more clearly the need for humility in rendering judgment, even harsh judgment, on the Catholic actors, especially the leading Catholic actors of the period. As José Sanchez, with whose conclusions in his book on understanding the controversy surrounding the wartime pope I otherwise largely disagree, has rightly pointed out, “it is easy to second guess after the events.”1 This somewhat uninflected observation means, I take it, that, in the case of the Holy See and the Holocaust, the calculus of whether to speak or to act was reached in the cauldron of a savage world war, wrought in the matrix of competing interests and complicated by uncertainty as to whether acting or speaking would result in relief for or reprisal. -

Célia Maria Silva Oliveira 995 – 20

Universidade do Minho Instituto de Letras e Ciências Humanas 0) 1 Célia Maria Silva Oliveira 995 – 20 From the Margins into the Mainstream: y Williams and Black British Theatre (1 Roy Williams and Black British Theatre (1995 – 2010) tream: Ro he Mains he Margins into t rom t F Célia Maria Silva Oliveira 2 1 UMinho|20 outubro de 2012 Universidade do Minho Instituto de Letras e Ciências Humanas Célia Maria Silva Oliveira From the Margins into the Mainstream: Roy Williams and Black British Theatre (1995 – 2010) Dissertação de Mestrado Mestrado em Estudos Ingleses Trabalho realizado sob a orientação da Professora Doutora Francesca Clare Rayner outubro de 2012 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Professor Francesca Rayner for introducing me to the world of New Writing in Britain and leading me in a quest of discovery. Thank you for the support and for believing in me and in the work that I could do. Thank you for the always open office door and the kind words. Filipe Couto, thank you for seeing qualities in me that I was not aware they existed. Thank you for the image that I have in your eyes. Sérgio Oliveira, more than my brother, my best friend, thank you for the support and the technical help. Sometimes, writing a thesis might have moments of desperation and Daniela and Neuza were always at the distance of a phone call. Thank you for the readings and for listening to my monologues. I would also want to thank all the people that direct and indirectly helped me and were part of this journey. -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible. -

N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd”

Platform , Vol. 3, No. 1 N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd” Neema Parvini (Royal Holloway, University of London) In 1958, in the Observer , Kenneth Tynan wrote of “a dazzling new playwright,” with his inimitable enthusiasm he declared: “I am ready to burn my boats and promise [that] N.F. Simpson [is] the most gifted comic writer the English stage has discovered since the war” (Tynan 210). Now, in 2008, despite a recent West End revival, 1 few critics would cite Simpson at all and debates regarding the “most gifted comic writer” of the English stage would invariably be centred on Tom Stoppard, Joe Orton, Samuel Beckett or, for those with a more morose sense of humour, Harold Pinter. Part of the reason for Simpson’s critical decline can be put down to protracted periods of silence; after his run of critically and commercially successful plays with The English Stage Company, 2 Simpson only produced two further full length plays: The Cresta Run (1965) and Was He Anyone? (1972). Of these, the former was poorly received and the latter only reached the fringe theatre. 3 As Stephen Pile recently put it, “in 1983, Simpson himself vanished” with no apparent fixed address. The other reason that may be cited is that, more than any other British writer of his time, Simpson was associated with “The Theatre of the Absurd.” As the vogue for the style died out in London, Simpson’s brand of Absurdism simply went out of fashion. John Russell Taylor offers perhaps the most scathing version of that argument: “whether one likes or dislikes N.F. -

Genocide, Memory and History

AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH AFTERMATH AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH Aftermath: Genocide, Memory and History © Copyright 2015 Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the chapter’s author/s. Copyright of this edited collection is held by Karen Auerbach. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/agmh-9781922235633.html Design: Les Thomas ISBN: 978-1-922235-63-3 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-922235-64-0 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-876924-84-3 (epub) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Aftermath : genocide, memory and history / editor Karen Auerbach ISBN 9781922235633 (paperback) Series: History Subjects: Genocide. Genocide--Political aspects. Collective memory--Political aspects. Memorialization--Political aspects. Other Creators/Contributors: Auerbach, Karen, editor. Dewey Number: 304.663 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................... -

Blanche Mcintyre Director / Writer

Blanche McIntyre Director / Writer * Winner - Best Director: TMA 2013 UK Theatre Awards * Winner of the 2011 Critcs' Circle Most Promising Newcomer Award for ACCOLADE and FOXFINDER (both at the Finborough Theatre) * FOXFINDER: Listed in Independent's top 5 picks for 2011 * ACCOLADE: Best Director and Best Production at Off West End Theatre Awards 2011; Listed in the Spectator's Top Ten Plays for 2011; Time Out's Best Fringe Show 2011 National Theatre Studio Director's Course (2010) Winner - Leverhulme Bursary (2009) Agents Giles Smart Assistant Ellie Byrne [email protected] +44 (020 3214 0812 Credits In Development Production Company Notes THE LITTLE FOXES Gate Theatre, Dublin By Lillian Hellman 2020 Theatre Production Company Notes HYMN Almeida / Sky Arts By Lolita Chakrabarti 2021 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes BOTTICELLI IN THE FIRE Hampstead By Jordan Tannahill 2019 BARTHOLOMEW FAIR Shakespeare's Globe - By Ben Jonson 2019 Sam Wanamaker Playhouse TARTUFFE National Theatre By Molière 2019 Adapted by John Donnelly & Director Blanche McIntyre WOMEN IN POWER Nuffield Based on Aristophanes' 2018 ASSEMBLY WOMEN THE WINTER'S TALE Shakespeare's Globe By William Shakespeare 2018 THE WRITER Almeida By Ella Hickson 2018 TITUS ANDRONICUS RSC By William Shakespeare 2017 THE NORMAN CONQUESTS Chichester Festival By Alan Ayckbourn 2017 Theatre THE TWO NOBLE KINSMEN RSC: The Swan By William Shakespeare 2016 NOISES -

Challenging Lesbian and Gay Inequalities in Education. Gender and Education Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-335-19130-4 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 253P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 398 296 UD 031 103 AUTHOR Epstein, Debbie, Ed. TITLE Challenging Lesbian and Gay Inequalities in Education. Gender and Education Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-335-19130-4 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 253p. AVAILABLE FROMOpen University Press, Celtic Court, 22 Ballmoor, Buckingham, MK18 1KW, England, United Kingdom ($27.50); Open University Press, 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academie Achievement; Elementary Secondary Education; *Equal Education; Foreign Countries; *Homophobia; *Homosexuality; Minority Groups; Peer Acceptance; Peer Relationship; *Self Esteem; Sex Education; *Social Discrimination; Social Support Groups; *Student Attitudes IDENTIFIERS *Bisexuality; Homosexual Teachers; United Kingdom ABSTRACT Educators in Britain have tended to ignore lesbian and gay issues, creating a gap that this book addresses by discussing the complex debates about sexuality and schooling. Contributors to this collection tell stories of distress and victimization and of achievement and support in the following: (1) "Introduction: Lesbian and Gay Equality in Education--Problems and Possibilities" (Debbie Epstein); (2)"So the Theory Was Fine" (Alistair, Dave, Rachel, and Teresa);(3) "Growing Up Lesbian: The Role of the School" (Marigold Rogers);(4) "A Burden of Aloneness" (Kola) ;(5) "Are You a Lesbian, Miss?" (Susan A. L. Sanders and Helena Burke);(6) "Victim of a Victimless Crime: Ritual and Resistance" -

The Shoah on Screen – Representing Crimes Against Humanity Big Screen, Film-Makers Generally Have to Address the Key Question of Realism

Mémoi In attempting to portray the Holocaust and crimes against humanity on the The Shoah on screen – representing crimes against humanity big screen, film-makers generally have to address the key question of realism. This is both an ethical and an artistic issue. The full range of approaches has emember been adopted, covering documentaries and fiction, historical reconstructions such as Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, depicting reality in all its details, and more symbolic films such as Roberto Benigni’s Life is beautiful. Some films have been very controversial, and it is important to understand why. Is cinema the best way of informing the younger generations about what moire took place, or should this perhaps be left, for example, to CD-Roms, videos Memoi or archive collections? What is the difference between these and the cinema as an art form? Is it possible to inform and appeal to the emotions without being explicit? Is emotion itself, though often very intense, not ambivalent? These are the questions addressed by this book which sets out to show that the cinema, a major art form today, cannot merely depict the horrors of concentration camps but must also nurture greater sensitivity among increas- Mémoire ingly younger audiences, inured by the many images of violence conveyed in the media. ireRemem moireRem The Shoah on screen – www.coe.int Representing crimes The Council of Europe has 47 member states, covering virtually the entire continent of Europe. It seeks to develop common democratic and legal princi- against humanity ples based on the European Convention on Human Rights and other reference texts on the protection of individuals.