Little America" and Dismantling "Little Tokyo"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utah Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Utah Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of the Nickerson Family, Japanese American National Museum (97.51.3) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Utah Curriculum Writing Team RaDon Andersen Jennifer Baker David Brimhall Jade Crown Sandra Early Shanna Futral Linda Oda Dave Seiter Photo by Motonobu Koizumi Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum UTAH Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 Topaz (Grade 4, 5, 6) Resources and References 34 Terminology and the Japanese American Experience 35 United States Confinement Sites for Japanese Americans During World War II 36 Japanese Americans in the Interior West: A Regional Perspective on the Enduring Nikkei Historical Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Utah (and Beyond) 60 State Overview Essay and Timeline 66 Selected Bibliography Appendix 78 Project Teams 79 Acknowledgments 80 Project Supporters * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). -

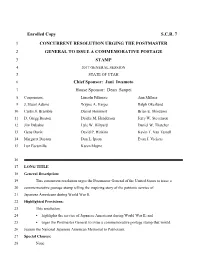

Enrolled Copy S.C.R. 7 1 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION

Enrolled Copy S.C.R. 7 1 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION URGING THE POSTMASTER 2 GENERAL TO ISSUE A COMMEMORATIVE POSTAGE 3 STAMP 4 2017 GENERAL SESSION 5 STATE OF UTAH 6 Chief Sponsor: Jani Iwamoto 7 House Sponsor: Dean Sanpei 8 Cosponsors: Lincoln Fillmore Ann Millner 9 J. Stuart Adams Wayne A. Harper Ralph Okerlund 10 Curtis S. Bramble Daniel Hemmert Brian E. Shiozawa 11 D. Gregg Buxton Deidre M. Henderson Jerry W. Stevenson 12 Jim Dabakis Lyle W. Hillyard Daniel W. Thatcher 13 Gene Davis David P. Hinkins Kevin T. Van Tassell 14 Margaret Dayton Don L. Ipson Evan J. Vickers 15 Luz Escamilla Karen Mayne 16 17 LONG TITLE 18 General Description: 19 This concurrent resolution urges the Postmaster General of the United States to issue a 20 commemorative postage stamp telling the inspiring story of the patriotic service of 21 Japanese Americans during World War II. 22 Highlighted Provisions: 23 This resolution: 24 < highlights the service of Japanese Americans during World War II; and 25 < urges the Postmaster General to issue a commemorative postage stamp that would 26 feature the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism. 27 Special Clauses: 28 None S.C.R. 7 Enrolled Copy 29 30 Be it resolved by the Legislature of the state of Utah, the Governor concurring therein: 31 WHEREAS, over 33,000 Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans), including 32 citizens of Utah, served with honor in the United States Army during World War II; 33 WHEREAS, as described in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, "race prejudice, war 34 hysteria, and a failure of -

Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: the Tule Lake Pilgrimage

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 6-9-2016 "Yes, No, Maybe": Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: The uleT Lake Pilgrimage Ella-Kari Loftfield Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Loftfield, Ella-Kari. ""Yes, No, Maybe": Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: The uleT Lake Pilgrimage." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ella-Kari Loftfield Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Professor Melissa Bokovoy, Chairperson Professor Jason Scott Smith Professor Barbara Reyes i “YES, NO, MAYBE−” LOYALTY AND BETRAYAL RECONSIDERED: THE TULE LAKE PILGRIMAGE By Ella-Kari Loftfield B.A., Social Anthropology, Haverford College, 1985 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2016 ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my father, Robert Loftfield whose enthusiasm for learning and scholarship knew no bounds. iii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people. Thanks to Peter Reed who has been by my side and kept me well fed during the entire experience. Thanks to the Japanese American National Museum for inviting me to participate in curriculum writing that lit a fire in my belly. -

Look Toward the Mountain, Episode 6 Transcript

LOOK TOWARD THE MOUNTAIN, EPISODE 6 TRANSCRIPT ROB BUSCHER: Welcome to Look Toward the Mountain: Stories from Heart Mountain Incarceration Camp, a podcast series about life inside the Heart Mountain Japanese American Relocation Center in northwestern Wyoming during World War II. I’m your host, Rob Buscher. This podcast is presented by the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and is funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. ROB BUSCHER: The sixth episode titled “Organizing Resistance” will explore how the Japanese American tradition of organizing evolved in camp to become a powerful resistance movement that dominated much of the Heart Mountain experience in its later years. INTRO THEME ROB BUSCHER: For much of history, Japanese traditional society was governed by the will of its powerful military warlords. Although in principle the shogun and his vassal daimyo ruled by force, much of daily life within the clearly delineated class system of Japanese society relied on consensus-building and mutual accountability. Similar to European Feudalism, the Japanese Han system created a strict hierarchy that privileged the high-born samurai class over the more populous peasantry who made up nearly 95% of the total population. Despite their low rank, food-producing peasants were considered of higher status than the merchant class, who were perceived to only benefit themselves. ROB BUSCHER: During the Edo period, peasants were organized into Gonin-gumi - groups of five households who were held mutually accountable for their share of village taxes, which were paid from a portion of the food they produced. If their gonin-gumi did not meet their production quota, all the peasants in their group would be punished. -

Migration and Transnationalism of Japanese Americans in the Pacific, 1930-1955

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ BEYOND TWO HOMELANDS: MIGRATION AND TRANSNATIONALISM OF JAPANESE AMERICANS IN THE PACIFIC, 1930-1955 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Michael Jin March 2013 The Dissertation of Michael Jin is approved: ________________________________ Professor Alice Yang, Chair ________________________________ Professor Dana Frank ________________________________ Professor Alan Christy ______________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Michael Jin 2013 Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: 19 The Japanese American Transnational Generation in the Japanese Empire before the Pacific War Chapter 2: 71 Beyond Two Homelands: Kibei and the Meaning of Dualism before World War II Chapter 3: 111 From “The Japanese Problem” to “The Kibei Problem”: Rethinking the Japanese American Internment during World War II Chapter 4: 165 Hotel Tule Lake: The Segregation Center and Kibei Transnationalism Chapter 5: 211 The War and Its Aftermath: Japanese Americans in the Pacific Theater and the Question of Loyalty Epilogue 260 Bibliography 270 iii Abstract Beyond Two Homelands: Migration and Transnationalism of Japanese Americans in the Pacific, 1930-1955 Michael Jin This dissertation examines 50,000 American migrants of Japanese ancestry (Nisei) who traversed across national and colonial borders in the Pacific before, during, and after World War II. Among these Japanese American transnational migrants, 10,000-20,000 returned to the United States before the outbreak of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and became known as Kibei (“return to America”). Tracing the transnational movements of these second-generation U.S.-born Japanese Americans complicates the existing U.S.-centered paradigm of immigration and ethnic history. -

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians Act

COMMISSION ON WARTIME RELOCATION AND INTERNMENT OF CIVILIANS ACT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE NINETY-SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON S. 1647 MARCH 18, 1980 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 63-293 O WASHINGTON : 1980 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS ABRAHAM RIBICOFF, Connecticut, Chairman HENRY M. JACKSON, Washington CHARLES H. PERCY, Illinois THOMAS F. EAGLETON, Missouri JACOB K. JAVITS, New York LAWTON CHILES, Florida WILLIAM V. ROTH, Jr., Delaware SAM NUNN, Georgia TED STEVENS, Alaska JOHN GLENN, Ohio CHARLES McC. MATHIAS, Jr., Maryland JIM SASSER, Tennessee JOHN C. DANFORTH, Missouri DAVID PRYOR, Arkansas WILLIAM S. COHEN, Maine CARL LEVIN, Michigan DAVID DURENBERGER, Minnesota R ic h a r d A. W e g m a n , Chief Counsel and Staff Director M a r ily n A. H a r r is, Executive Administrator and Professional Staff Member Co n st a n c e B. E v a n s , Minority Staff Director E l iza b eth A. P r ea st, Chief Clerk \ CONTENTS Opening statements: Pa^e Senator Jackson............................................................................................................. 1 Senator Inouye................................................................................................................ 1 Senator Levin.................................................................................................................. 2 Senator Matsunaga..................................................................................................... -

Page 8 DUE ‘ALLEGIANCE’ the New Musical Play Creates a Buzz Within the Japanese American Community

SPecial iSSue: 2012 jacl Scholarship Winners The NATIONAL NeWSPAPeR Of The JACL Page 8 Due ‘alleGiaNce’ The new musical play creates a buzz within the japanese american community. # 3198 / VOL. 155, NO. 7 ISSN: 0030-8579 WWW.PACIFICCITIZEN.ORG OctoBER 5-18, 2012 2 Oct. 5 -18, 2012 SPECIAL SCHOLARSHIP ISSUE HOW to REACH US E-mail: [email protected] 2012 NATIONAL JACL SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS Online: www.pacificcitizen.org Tel: (213) 620-1767 This year’s National JACL Scholarship Program has come to a close. In this special issue, the JACL is Fax: (213) 620-1768 Mail: 250 E. First Street, Suite 301 pleased to award a total of $61,000 to the 25 most-deserving applicants in their respective categories. Los Angeles, CA 90012 Staff With so many well-qualified students, the future of the JACL is in good hands. Executive Editor Assistant Editor his year, the student applicants were asked to by our chapters, selection committee members and national address the following statement: “One young person staff to ensure the program’s success. We congratulate our Reporter Nalea J. Ko remarked, ‘Our generation believes in civil rights, but 2012 student scholars and wish them well. don’tT feel we need to join a civil rights organization like the In 2013, I’m excited to announce the foundation of a new Business Manager JACL.’” relationship with Meiji Gakuin University in Japan. This is an Susan Yokoyama As you read their responses on the following pages, I opportunity for one qualified student to be awarded a four- Circulation believe you will be enlightened, impressed and inspired. -

Utah Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Utah Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of the Nickerson Family, Japanese American National Museum (97.51.3) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Utah Curriculum Writing Team RaDon Andersen Jennifer Baker David Brimhall Jade Crown Sandra Early Shanna Futral Linda Oda Dave Seiter Photo by Motonobu Koizumi Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum UTAH Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 The World War II Japanese American Experience: -

The Utah Nippo, Salt Lake City's Japanese Americans, and Proving Group Loyalty, 1941-1946

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2012 "Super Salesmen" for the Toughest Sales Job: The Utah Nippo, Salt Lake City's Japanese Americans, and Proving Group Loyalty, 1941-1946 Sarah Fassmann Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Fassmann, Sarah, ""Super Salesmen" for the Toughest Sales Job: The Utah Nippo, Salt Lake City's Japanese Americans, and Proving Group Loyalty, 1941-1946" (2012). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1286. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1286 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SUPER SALESMEN” FOR THE TOUGHEST SALES JOB: THE UTAH NIPPO, SALT LAKE CITY’S JAPANESE AMERICANS, AND PROVING GROUP LOYALTY, 1941–1946 by Sarah B. Fassmann A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: David Rich Lewis Lawrence Culver Major Professor Committee Member Melody Graulich Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2012 ii Copyright © Sarah L. B. Fassmann 2012 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “Super Salesmen” for the Toughest Sales Job: The Utah Nippo, Salt Lake City’s Japanese Americans, and Proving Group Loyalty, 1941–1946 by Sarah L. B. Fassmann, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2012 Major Professor: Dr. -

A History of Japanese American Internment Camps

A Happier New Year from Poston Happier New Year from Poston 1 Terminology and Definitions For the sake of consistency and conformity with the "Resolution Regarding Terminology" adopted by the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund (CLPEF), this research paper uses the term “incarceration” rather than “internment” to describe the confinement in the U.S. of Japanese Americans during World War II. As noted on the “Terminology and Glossary” page of the Densho website, the term "internment" is problematic when applied to American citizens. Technically, internment refers to the detention of enemy aliens during time of war, and two-thirds of the Japanese Americans incarcerated were U.S. citizens. Although it is a recognized and generally used term even today, we prefer "incarceration" as more accurate except in the specific case of aliens. (n.p.) As acknowledged above, it should be noted that due to the varying attitudes and lack of consensus on the need for and administration of the mass incarceration/internment, many observers (including Japanese Americans) use the term “internment” (“internee”, “interned”, etc.) and not “incarceration” (“incarcerated”). It should be further noted that some observers prefer the term “concentration” to describe the camps. In fact, in a 1944 press conference and a 1962 interview on the subject, Presidents Roosevelt and Truman, respectively, employed the term “concentration camp”. (Densho) Some terms used in this paper are defined as follows (Source: “Terminology and Glossary” page of the Densho website) Issei: the first generation of immigrant Japanese Americans, most of whom came to the United States between 1885 and 1924. The Issei were ineligible for U.S. -

Rocky Shimpo 1947

Rocky Shimpo Editorials, May 16, 1947–December 15, 1947, by James M. Omura Edited by Arthur A. Hansen In 2003, I authored an article entitled “Return to the Wars: Jimmie Omura’s 1947 Crusade against the Japanese American Citizens League.” Assuredly, it had been Omura’s animus against the JACL that fueled the “wars” to which, in mid-May 1947, he was “returning” as the newly reappointed English-section editor of Denver, Colorado’s Rocky Shimpo vernacular newspaper. After all, only three years previously, due in great measure to the behind-the-scenes machinations of the JACL national and regional leadership, Omura was flushed out of his initial four-month tenure, in early 1944, as the Rocky Shimpo’s English-section editor and subsequently―along with the seven leaders of the Fair Play Committee (FPC) at Wyoming’s Heart Mountain Relocation Center―indicted, arrested, jailed, and forced to stand trial in a Cheyenne, Wyoming, federal court for unlawful conspiracy to counsel, aid, and abet violations of the military draft. Even though Omura, unlike the FPC leadership, was acquitted of this charge, his legal vindication did not prevent the Denver-area JACL power brokers from mobilizing an extralegal vendetta against him within the Nikkei community. Indeed, they so effectively harassed and demonized Omura as to make it virtually impossible for him to gain sustainable employment or to revel in the rewards of a viable social and cultural life, and these deprivations in turn hastened his 1947 divorce from his Nisei wife, Fumiko “Caryl” Omura (née Okuma). The conventional historical narrative stamped on Omura’s life by his contemporary critics and latter-day chroniclers is that his militant 1934-1944 opposition to the JACL leadership of the Japanese American community and the U.S.-government’s wartime treatment of Japanese Americans was brought to a halt before the end of World War II. -

Fred Korematsu's Story

LESSON 1 Fred Korematsu’s Story 9 Time Materials 1 class period (block scheduling, 90 minutes per • Handout 1-1: Notes and Quotes period) or 2 class periods (45 minutes per period) • Brief biography of Fred Korematsu, written by Eric Yamamoto and May Lee, downloaded from the Asian Overview American Bar Association of the Greater Bay Area’s This lesson introduces the unit’s essential question Web site: http://www.aaba-bay.com/aaba/showpage. and the story of Fred Korematsu, a Nisei (second- asp?code=yamamotoarticle (accessed September 3, 2009). generation American-born citizen) from California who defied Civilian Exclusion Order No. 34 issued by An excerpt of this biography will be read aloud by the the government after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. teacher. Students will be encouraged to think about the con- • Teacher Worksheet A: Roles for the Mock Trial stitutionality of Executive Order 9066, specifically • Teacher Worksheet B: Sample Class Breakdowns as it relates to the United States Constitution’s Fifth • Teacher Worksheet C: Sample Class Assignments Amendment guarantee of due process and the Four- teenth Amendment’s promise of equal protection. Background At the conclusion of this lesson the mock trial is If necessary, review with students the historical con- introduced, and students will submit their choices for tent listed in the unit map. their roles in the trial. The teacher must be prepared to assign and present the students’ roles by Lesson 2. Before teaching this lesson, the teacher should calculate Essential Question how many students are needed to fill each role within the mock trial.