Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: the Tule Lake Pilgrimage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Private Memory on the Redress Movement of Japanese Americans

From Private Moments to Public Calls for Justice: The Effects of Private Memory on the Redress Movement of Japanese Americans A thesis submitted to the Department of History, Miami University, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Sarah Franklin Doran Miami University Oxford, Ohio May 201 ii ABSTRACT FROM PRIVATE MOMENTS TO PUBLIC CALLS FOR JUSTICE: THE EFFECTS OF PRIVVATE MEMORY ON THE REDRESS MOVEMENT OF JAPANESE AMERICANS Sarah Doran It has been 68 years since President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the internment of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans. This period of internment would shape the lives of all of those directly involved and have ramifications even four generations later. Due to the lack of communication between family members who were interned and their children, the movement for redress was not largely popular until the 1970s. Many families classified their time in the internment camps as subjects that were off limits, thus, leaving children without the true knowledge of their heritage. Because memories were not shared within the household, younger generations had no pressing reason to fight for redress. It was only after an opening in the avenue of communication between the generations that the search for true justice could commence. The purpose of this thesis is to explore how communication patterns within the home, the Japanese-American community, and ultimately the nation changed to allow for the successful completion of a reparation movement. What occurred to encourage those who were interned to end their silence and share their experiences with their children, grandchildren, and the greater community? Further, what external factors influenced this same phenomenon? The research for this project was largely accomplished through reading memoirs and historical monographs. -

1986 Journal

OCTOBER TERM, 1986 Reference Index Contents: page Statistics n General in Appeals in Arguments iv Attorneys iv Briefs iv Certiorari v Costs v Judgments and Opinions v Original Cases vi Parties vii Stays vn Conclusion vn (i) II STATISTICS AS OF JUNE 26, 1987 In Forma Paid Original Pauperis Total Cases Cases Number of cases on docket 12 2,547 2,564 5,123 Cases disposed of 1 2,104 2,241 4,349 Remaining on docket 11 440 323 774 Cases docketed during term: Paid cases 2,071 In forma pauperis cases 2, 165 Original cases 4 Total 4,240 Cases remaining from last term 883 Total cases on docket 5, 123 Cases disposed of 4,349 Number of remaining on docket 774 Petitions for certiorari granted: In paid cases 121 In in forma pauperis cases............... 14 Appeals granted: In paid cases 31 In in forma pauperis cases 1 Total cases granted plenary review 167 Cases argued during term 175 Number disposed of by full opinions 164 Number disposed of by per curiam opinions 10 Number set for reargument next term 1 Cases available for argument at beginning of term 101 Disposed of summarily after review was granted 4 Original cases set for argument 0 Cases reviewed and decided without oral argument 109 Total cases available for argument at start of next term 91 Number of written opinions of the Court 145 Opinions per curiam in argued cases 9 Number of lawyers admitted to practice as of October 4, 1987: On written motion 3,679 On oral motion...... 1,081 Total............................... -

Utah Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Utah Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of the Nickerson Family, Japanese American National Museum (97.51.3) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Utah Curriculum Writing Team RaDon Andersen Jennifer Baker David Brimhall Jade Crown Sandra Early Shanna Futral Linda Oda Dave Seiter Photo by Motonobu Koizumi Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum UTAH Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 Topaz (Grade 4, 5, 6) Resources and References 34 Terminology and the Japanese American Experience 35 United States Confinement Sites for Japanese Americans During World War II 36 Japanese Americans in the Interior West: A Regional Perspective on the Enduring Nikkei Historical Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Utah (and Beyond) 60 State Overview Essay and Timeline 66 Selected Bibliography Appendix 78 Project Teams 79 Acknowledgments 80 Project Supporters * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). -

Archived Thesis/Research Paper/Faculty Publication from The

Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ “Do it for your grandchildren” A Missed Opportunity: the Legacy of the Redress Movement’s Divide Dustin Eric Williams Senior Thesis for the Department of History Tracey Rizzo University of North Carolina Asheville 1 On December 7th, 1941, the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, an act which resulted in the death of 2,335 Navy Servicemen and 55 civilians. These immediate casualties became a rallying point for the United States entry into the Pacific Theater and World War II. However, the 2,335 Navy serviceman and 55 American civilians were not the only casualties of that day. Shortly after the attack in Pearl Harbor, two-thousand Japanese Americans were rounded up and incarcerated under suspicion of being possible Japanese sympathizers.1 They were followed within the next few weeks by around 120,000 others, only because their lineage traced back to the enemy. These citizens and their families would remain incarcerated until 1946, when the relocation camps were officially closed.2 From the camps they emerged fundamentally changed, becoming silent about their experiences. The culture of silence that followed was so prevalent that many of their children knew little to nothing about incarceration and internment.3 They felt that this silence was necessary in order to protect their children and their grandchildren from the shame of what had happened.4 Yet, as the memory of internment slowly crept back into the community, it birthed what we come to call today the Japanese Redress Movement; this protective nature toward their children later compelled around 750 Japanese Americans to testify about their experiences.5 The goals of the Redress movement included: A quest to absolve themselves of the accusations made against them during the war, an attempt to gain monetary reparations for 1 Mitchell T. -

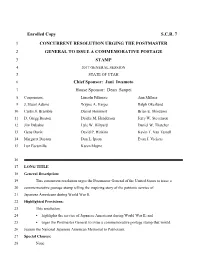

Enrolled Copy S.C.R. 7 1 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION

Enrolled Copy S.C.R. 7 1 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION URGING THE POSTMASTER 2 GENERAL TO ISSUE A COMMEMORATIVE POSTAGE 3 STAMP 4 2017 GENERAL SESSION 5 STATE OF UTAH 6 Chief Sponsor: Jani Iwamoto 7 House Sponsor: Dean Sanpei 8 Cosponsors: Lincoln Fillmore Ann Millner 9 J. Stuart Adams Wayne A. Harper Ralph Okerlund 10 Curtis S. Bramble Daniel Hemmert Brian E. Shiozawa 11 D. Gregg Buxton Deidre M. Henderson Jerry W. Stevenson 12 Jim Dabakis Lyle W. Hillyard Daniel W. Thatcher 13 Gene Davis David P. Hinkins Kevin T. Van Tassell 14 Margaret Dayton Don L. Ipson Evan J. Vickers 15 Luz Escamilla Karen Mayne 16 17 LONG TITLE 18 General Description: 19 This concurrent resolution urges the Postmaster General of the United States to issue a 20 commemorative postage stamp telling the inspiring story of the patriotic service of 21 Japanese Americans during World War II. 22 Highlighted Provisions: 23 This resolution: 24 < highlights the service of Japanese Americans during World War II; and 25 < urges the Postmaster General to issue a commemorative postage stamp that would 26 feature the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism. 27 Special Clauses: 28 None S.C.R. 7 Enrolled Copy 29 30 Be it resolved by the Legislature of the state of Utah, the Governor concurring therein: 31 WHEREAS, over 33,000 Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans), including 32 citizens of Utah, served with honor in the United States Army during World War II; 33 WHEREAS, as described in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, "race prejudice, war 34 hysteria, and a failure of -

III. Appellate Court Overturns Okubo-Yamada

III. appellate PACIFIC CrrlZEN court overturns Publication of the National Japanese American Citizens League Okubo-Yamada Vol. 86 No. 1 New Year Special: Jan. 6-13, 1978 20¢ Postpaid U.S. 15 Cents STOCKTON, Calif.-It was a go law firm of Baskin, festive Christmas for the Server and Berke. It is "ex Okubo and Yamada families tremely unlikely" the appel here upon hearing from late court would grant Hil their Chicago attorneys just ton Hotel a rehearing at the before the holidays that the appellate level nor receive Jr. Miss Pageant bars alien aspirants lllinois appellate court had permission to appeal to the SEATTLE-Pacific Northwest JACL leaders concede the "It would seem only right and proper that the pageant reversed the Cook County lllinois supreme court, fight to reinstate a 17-year-{)ld Vietnamese girl of Dayton, rules should be amended to include in their qualifications trial court decision and or Berke added. He said! Wash. who was denied the Touchet Valley Junior Miss dered the 1975 civil suit "The end result, after all of pageant candidates the words 'and aliens legally ad aeainst the Hilton Hotel title because she was not an American citizen has most these petitions, is that we are mitted as pennanent residents of the United States'," Ya Corp. to be reheard going to be given amthero~ likely been lost. mamoto wrote in a letter to the Spokane Spokesman Re The Okubo-Yamada case portunity to try this case or The state Junior Miss Pageant will be held at Wenat view. had alleged a breach of ex settle it before trial" chee Jan. -

Nursing in Japanese American Incarceration Camps, 1942-1945

Nursing in Japanese American Incarceration Camps, 1942-1945 Rebecca Ann Coffin Staunton, Virginia BSN, Georgetown University, 1989 MSN, St. Joseph’s College of Maine, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Nursing University of Virginia May, 2016 © Copyright by Rebecca A. Coffin All Rights Reserved May 2016 i Abstract Japanese Americans living in west coast states had been a marginalized group long before the attack against Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on December 7, 1941 by the Empire of Japan, which accelerated the maelstrom of hysteria and hatred against them. As a result, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing Secretary of War Stimson and designated military commanders to prescribe military areas from which any or all persons could be excluded. United States military leaders identified all Japanese Americans in the western portions of Washington, Oregon, and California as potential subversive persons that might rise up and sabotage the United States from within its borders. Over 110,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from their homes and transported to one of ten incarceration camps until their loyalty to the United States could be determined. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9102 established the War Relocation Authority on March 18, 1942. This civilian agency provided for the shelter, nutrition, education, and medical care of the excluded Japanese Americans as they waited to be redistributed within the interior and eastern United States. Previous literature describing the medical care furnished to the Japanese Americans in the camps concentrated on early system problems related to supplies and sanitation efforts. -

A a C P , I N C

A A C P , I N C . Asian Am erican Curriculum Project Dear Friends; AACP remains concerned about the atmosphere of fear that is being created by national and international events. Our mission of reminding others of the past is as important today as it was 37 years ago when we initiated our project. Your words of encouragement sustain our efforts. Over the past year, we have experienced an exciting growth. We are proud of publishing our new book, In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment, by the Northern California MIS Kansha Project and Shizue Seigel. AACP continues to be active in publishing. We have published thirteen books with three additional books now in development. Our website continues to grow by leaps and bounds thanks to the hard work of Leonard Chan and his diligent staff. We introduce at least five books every month and offer them at a special limited time introductory price to our newsletter subscribers. Find us at AsianAmericanBooks.com. AACP, Inc. continues to attend over 30 events annually, assisting non-profit organizations in their fund raising and providing Asian American book services to many educational organizations. Your contributions help us to provide these services. AACP, Inc. continues to be operated by a dedicated staff of volunteers. We invite you to request our catalogs for distribution to your associates, organizations and educational conferences. All you need do is call us at (650) 375-8286, email [email protected] or write to P.O. Box 1587, San Mateo, CA 94401. There is no cost as long as you allow enough time for normal shipping (four to six weeks). -

Historic Resource Study

Historic Resource Study Minidoka Internment National Monument _____________________________________________________ Prepared for the National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington Minidoka Internment National Monument Historic Resource Study Amy Lowe Meger History Department Colorado State University National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………… i Note on Terminology………………………………………….…………………..…. ii List of Figures ………………………………………………………………………. iii Part One - Before World War II Chapter One - Introduction - Minidoka Internment National Monument …………... 1 Chapter Two - Life on the Margins - History of Early Idaho………………………… 5 Chapter Three - Gardening in a Desert - Settlement and Development……………… 21 Chapter Four - Legalized Discrimination - Nikkei Before World War II……………. 37 Part Two - World War II Chapter Five- Outcry for Relocation - World War II in America ………….…..…… 65 Chapter Six - A Dust Covered Pseudo City - Camp Construction……………………. 87 Chapter Seven - Camp Minidoka - Evacuation, Relocation, and Incarceration ………105 Part Three - After World War II Chapter Eight - Farm in a Day- Settlement and Development Resume……………… 153 Chapter Nine - Conclusion- Commemoration and Memory………………………….. 163 Appendixes ………………………………………………………………………… 173 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………. 181 Cover: Nikkei working on canal drop at Minidoka, date and photographer unknown, circa 1943. (Minidoka Manuscript Collection, Hagerman Fossil -

Living Voices Within the Silence Bibliography 1

Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 1 Within the Silence bibliography FICTION Elementary So Far from the Sea Eve Bunting Aloha means come back: the story of a World War II girl Thomas and Dorothy Hoobler Pearl Harbor is burning: a story of World War II Kathleen Kudlinski A Place Where Sunflowers Grow (bilingual: English/Japanese) Amy Lee-Tai Baseball Saved Us Heroes Ken Mochizuki Flowers from Mariko Rick Noguchi & Deneen Jenks Sachiko Means Happiness Kimiko Sakai Home of the Brave Allen Say Blue Jay in the Desert Marlene Shigekawa The Bracelet Yoshiko Uchida Umbrella Taro Yashima Intermediate The Burma Rifles Frank Bonham My Friend the Enemy J.B. Cheaney Tallgrass Sandra Dallas Early Sunday Morning: The Pearl Harbor Diary of Amber Billows 1 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 2 The Journal of Ben Uchida, Citizen 13559, Mirror Lake Internment Camp Barry Denenberg Farewell to Manzanar Jeanne and James Houston Lone Heart Mountain Estelle Ishigo Itsuka Joy Kogawa Weedflower Cynthia Kadohata Boy From Nebraska Ralph G. Martin A boy at war: a novel of Pearl Harbor A boy no more Heroes don't run Harry Mazer Citizen 13660 Mine Okubo My Secret War: The World War II Diary of Madeline Beck Mary Pope Osborne Thin wood walls David Patneaude A Time Too Swift Margaret Poynter House of the Red Fish Under the Blood-Red Sun Eyes of the Emperor Graham Salisbury, The Moon Bridge Marcia Savin Nisei Daughter Monica Sone The Best Bad Thing A Jar of Dreams The Happiest Ending Journey to Topaz Journey Home Yoshiko Uchida 2 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 3 Secondary Snow Falling on Cedars David Guterson Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet Jamie Ford Before the War: Poems as they Happened Drawing the Line: Poems Legends from Camp Lawson Fusao Inada The moved-outers Florence Crannell Means From a Three-Cornered World, New & Selected Poems James Masao Mitsui Chauvinist and Other Stories Toshio Mori No No Boy John Okada When the Emperor was Divine Julie Otsuka The Loom and Other Stories R.A. -

Dorothea Lange's Censored Photographs of the Japanese

Volume 15 | Issue 3 | Number 1 | Article ID 5008 | Feb 01, 2017 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Dorothea Lange’s Censored Photographs of the Japanese American Internment Linda Gordon Abstract: Bloch; she was then married to prominent artist Maynard Dixon, and she socialized with While Dorothea Lange has long been widely artists, bohemians, and her wealthy clients. known and acclaimed for her photographs When Diego Rivera made his first visit to the depicting the impact of the Great Depression US in 1930, he fell in with that crowd and on farmers and laborers, her documentation of Lange loaned her studio to Frida Kahlo. the Japanese American internment was long impounded by the US army. This article tells In 1935, restless and bored with her studio the story and shows some of the signature photography, she took a job with the Farm images contained in her documentation of the Security Administration (FSA) of the internment as well as explaining their long Department of Agriculture. Her assignment suppression. was to document the impact of the depression on farmers and farmworkers; these photographs were widely published as a means of building support for President Franklin Roosevelt’s agricultural policies. These photographs, however, then appeared without Shortly after Franklin Roosevelt ordered the the name of their creator. Since then, however, internment of Japanese Americans in 1942, the she has become most famous for this work: her War Location Authority hired photographer photographs of migrant farmworkers and Dorothea Lange to document the process. I sharecroppers have been so widely published strongly suspect that whoever made the that those who do not know her name almost decision knew little about her previous work, always recognize her pictures. -

Product Catalog

FILMS | VIDEOS | ANIMATION | EXHIBITS | PUBLICATIONS | MULTI-MEDIA | ARCHIVES VISUAL COMMUNICATIONS PRODUCT CATALOG 2017-2018 CONTENTS 03 | Welcome 04 | About Visual Communications 06 | Product Highlights 10 | Speak Out for Justice Volumes 14 | Armed With a Camera Volumes 22 | Digital Histories Volumes 30 | VC Classics 32 | Hidden Treasures Series 34 | Documentary 36 | Narrative 37 | Graphic Film/Animation 38 | Video 43 | Filmmakers Development Program 47 | Other Works 48 | Multi-Media 49 | Photographic Exhibitions 51 | Publications 52 | Resources 54 | Rental and Sales Info 57 | Policies Oversize Image Credits: Cover: PAGE 10: Roy Nakano; PAGE 43: From HITO HATA: RAISE THE BANNER (1980) by Robert A. Nakamura and Duane Kubo (Visual Communications Photographic Archive) ALL OTHER IMAGES APPEARING IN THIS CATALOG: Courtesy The Visual Communications Photographic Archive PRODUCTION CREDITS: Project Producer: Shinae Yoon; Editor: Helen Kim; Copywriter: Jerome Academia, Helen Kim, Jeff Liu, Supachai Surongsain; Design and Layout: Abraham Ferrer; Digital Photo-imaging intern: Allison Nakamura 02 WELCOME The visual heritage of Visual Communications can be seen in the more than 100 films, videos, and multimedia productions created since the organization’s founding in 1970. Beginning with vanguard works filmed in Super 8mm, Visual Communications productions have been distinguished by their unerring fidelity to the stories and perspectives of Asian America. As evidenced within this catalog, this policy has continued as Visual Communications’ productions have transitioned from film and video to digital formats. As well, the stories being told through our various offerings reflect the ever-changing landscape of the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities, and introduces us to filmmakers and voices who have come of age in the 22 years since the first edition of this catalog.