Migration and Transnationalism of Japanese Americans in the Pacific, 1930-1955

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening the Island

Mayumi Itoh. Globalization of Japan : Japanese Sakoku mentality and U. S. efforts to open Japan. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998. 224 pp. $45.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-312-17708-9. Reviewed by Sandra Katzman Published on H-US-Japan (February, 1999) Japan is ten years into its third kaikoku, or reader in the Japanese mentality through these open door policy, in modern history. phrases without requiring Japanese or Chinese This book is well-organized into two parts: scripts. Some of the most important words are "The Japanese Sakoku Mentality" and "Japan's Kokusaika: internationalization Gaijin: out‐ Sakoku Policy: Case Studies." Although its subject sider, foreigner Kaikoku: open-door policy includes breaking news, such as the rice tariffs, Saikoku: secluded nation Gaiatsu: external pres‐ the book has a feeling of completion. The author, sure Mayumi Itoh, has successfully set the subject in Part I has fve chapters: Historical Back‐ history, looking backward and looking forward. ground, the Sakoku Mentality and Japanese Per‐ Itoh is Associate Professor of Political Science at ceptions of Kokusaika, Japanese Perceptions of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. the United States, Japanese Perceptions of Asia, Itoh argues that although globalization is a and Japanese Perceptions of ASEAN and Japan's national policy of Japan, mental habits preclude Economic Diplomacy. its success. She sets the globalization as the third Part II has fve chapters: Japan's Immigration in a series of outward expansions, each one pre‐ and Foreign Labor Policies, Okinawa and the cipitated by the United States. The style of writing Sakoku Mentality, Kome Kaikoku: Japan's Rice is scholarly and easy to understand. -

The Effects of Private Memory on the Redress Movement of Japanese Americans

From Private Moments to Public Calls for Justice: The Effects of Private Memory on the Redress Movement of Japanese Americans A thesis submitted to the Department of History, Miami University, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Sarah Franklin Doran Miami University Oxford, Ohio May 201 ii ABSTRACT FROM PRIVATE MOMENTS TO PUBLIC CALLS FOR JUSTICE: THE EFFECTS OF PRIVVATE MEMORY ON THE REDRESS MOVEMENT OF JAPANESE AMERICANS Sarah Doran It has been 68 years since President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the internment of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans. This period of internment would shape the lives of all of those directly involved and have ramifications even four generations later. Due to the lack of communication between family members who were interned and their children, the movement for redress was not largely popular until the 1970s. Many families classified their time in the internment camps as subjects that were off limits, thus, leaving children without the true knowledge of their heritage. Because memories were not shared within the household, younger generations had no pressing reason to fight for redress. It was only after an opening in the avenue of communication between the generations that the search for true justice could commence. The purpose of this thesis is to explore how communication patterns within the home, the Japanese-American community, and ultimately the nation changed to allow for the successful completion of a reparation movement. What occurred to encourage those who were interned to end their silence and share their experiences with their children, grandchildren, and the greater community? Further, what external factors influenced this same phenomenon? The research for this project was largely accomplished through reading memoirs and historical monographs. -

1986 Journal

OCTOBER TERM, 1986 Reference Index Contents: page Statistics n General in Appeals in Arguments iv Attorneys iv Briefs iv Certiorari v Costs v Judgments and Opinions v Original Cases vi Parties vii Stays vn Conclusion vn (i) II STATISTICS AS OF JUNE 26, 1987 In Forma Paid Original Pauperis Total Cases Cases Number of cases on docket 12 2,547 2,564 5,123 Cases disposed of 1 2,104 2,241 4,349 Remaining on docket 11 440 323 774 Cases docketed during term: Paid cases 2,071 In forma pauperis cases 2, 165 Original cases 4 Total 4,240 Cases remaining from last term 883 Total cases on docket 5, 123 Cases disposed of 4,349 Number of remaining on docket 774 Petitions for certiorari granted: In paid cases 121 In in forma pauperis cases............... 14 Appeals granted: In paid cases 31 In in forma pauperis cases 1 Total cases granted plenary review 167 Cases argued during term 175 Number disposed of by full opinions 164 Number disposed of by per curiam opinions 10 Number set for reargument next term 1 Cases available for argument at beginning of term 101 Disposed of summarily after review was granted 4 Original cases set for argument 0 Cases reviewed and decided without oral argument 109 Total cases available for argument at start of next term 91 Number of written opinions of the Court 145 Opinions per curiam in argued cases 9 Number of lawyers admitted to practice as of October 4, 1987: On written motion 3,679 On oral motion...... 1,081 Total............................... -

Utah Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Utah Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of the Nickerson Family, Japanese American National Museum (97.51.3) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Utah Curriculum Writing Team RaDon Andersen Jennifer Baker David Brimhall Jade Crown Sandra Early Shanna Futral Linda Oda Dave Seiter Photo by Motonobu Koizumi Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum UTAH Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 Topaz (Grade 4, 5, 6) Resources and References 34 Terminology and the Japanese American Experience 35 United States Confinement Sites for Japanese Americans During World War II 36 Japanese Americans in the Interior West: A Regional Perspective on the Enduring Nikkei Historical Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Utah (and Beyond) 60 State Overview Essay and Timeline 66 Selected Bibliography Appendix 78 Project Teams 79 Acknowledgments 80 Project Supporters * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). -

A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas Caleb Kenji Watanabe University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2011 Islands and Swamps: A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas Caleb Kenji Watanabe University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Other History Commons, and the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Watanabe, Caleb Kenji, "Islands and Swamps: A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 206. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/206 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ISLANDS AND SWAMPS: A COMPARISON OF THE JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT EXPERIENCE IN HAWAII AND ARKANSAS ISLANDS AND SWAMPS: A COMPARISON OF THE JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT EXPERIENCE IN HAWAII AND ARKANSAS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Caleb Kenji Watanabe Arkansas Tech University Bachelor of Arts in History, 2009 December 2011 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT Comparing the Japanese American relocation centers of Arkansas and the camp systems of Hawaii shows that internment was not universally detrimental to those held within its confines. Internment in Hawaii was far more severe than it was in Arkansas. This claim is supported by both primary sources, derived mainly from oral interviews, and secondary sources made up of scholarly research that has been conducted on the topic since the events of Japanese American internment occurred. -

Immigration Discourses in the U.S. and in Japan Chie Torigoe

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Communication ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2011 Immigration Discourses in the U.S. and in Japan Chie Torigoe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cj_etds Recommended Citation Torigoe, Chie. "Immigration Discourses in the U.S. and in Japan." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cj_etds/25 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i IMMIGRATION DISCOURSES IN THE U.S. AND IN JAPA by CHIE TORIGOE B.A., Linguistics, Seinan Gakuin University, 2003 M.A., Communication Studies, Seinan Gakuin University, 2005 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Communication The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2011 ii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of Dr. Tadasu Todd Imahori, a passionate scholar, educator, and mentor who encouraged me to pursue this path. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to those who made this challenging journey possible, memorable and even enjoyable. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Mary Jane Collier. Mary Jane, without your constant guidance and positive support, I could not make it this far. Throughout this journey, you have been an amazing mentor to me. Your intelligence, keen insight and passion have always inspired me, and your warm, nurturing nature and patience helped me get through stressful times. -

Archived Thesis/Research Paper/Faculty Publication from The

Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ “Do it for your grandchildren” A Missed Opportunity: the Legacy of the Redress Movement’s Divide Dustin Eric Williams Senior Thesis for the Department of History Tracey Rizzo University of North Carolina Asheville 1 On December 7th, 1941, the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, an act which resulted in the death of 2,335 Navy Servicemen and 55 civilians. These immediate casualties became a rallying point for the United States entry into the Pacific Theater and World War II. However, the 2,335 Navy serviceman and 55 American civilians were not the only casualties of that day. Shortly after the attack in Pearl Harbor, two-thousand Japanese Americans were rounded up and incarcerated under suspicion of being possible Japanese sympathizers.1 They were followed within the next few weeks by around 120,000 others, only because their lineage traced back to the enemy. These citizens and their families would remain incarcerated until 1946, when the relocation camps were officially closed.2 From the camps they emerged fundamentally changed, becoming silent about their experiences. The culture of silence that followed was so prevalent that many of their children knew little to nothing about incarceration and internment.3 They felt that this silence was necessary in order to protect their children and their grandchildren from the shame of what had happened.4 Yet, as the memory of internment slowly crept back into the community, it birthed what we come to call today the Japanese Redress Movement; this protective nature toward their children later compelled around 750 Japanese Americans to testify about their experiences.5 The goals of the Redress movement included: A quest to absolve themselves of the accusations made against them during the war, an attempt to gain monetary reparations for 1 Mitchell T. -

Fall October 2016

Asian Pacific American Community Newspaper Serving Sacramento and Yolo Counties - Volume 29, No. 3 Fall/October 2016 Register & Vote API vote sought by INSIDE CURRENTS ACC Senior Services - 3 Will you be 18 years old and a US major parties Iu-Mien Commty Svc - 5 citizen by November 4th? YES?? YOU While much attention is focused on GET TO VOTE!! But you need to register Hispanic and black voters, Asian Pacific Islander Chinese Am Council of Sac-7 to vote by Monday October 24th. are the single fastest growing demographic group and that has drawn the attention of You can register to vote online at major political parties. In states like Nevada sos.ca.gov (Secretary of State website), and Virginia, where polls show that the ask your local county elections office to presidential race is down to single digits, the Sacramento APIs send you a voter registration form or go API vote can swing the outcome of national and local elections. API voters are 8.5 - 9% of targeted by robbers in person to your local elections office. the voters in Nevada, 5 - 6.5% in Virginia, 7% Voter registration forms online are in New Jersey, 3.1% in Minnesota, and 15% in The Sacramento police announced available in 12 languages. California. In a tight race, the API vote can make that about 20 people have been arrested for a difference. Nine million APIs will be eligible to armed robberies targeting API residents. The vote in November, up 16% from four years ago. police say that the suspects do not appear to Nationally, API voters are about 4%. -

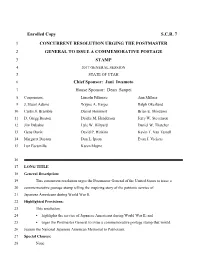

Enrolled Copy S.C.R. 7 1 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION

Enrolled Copy S.C.R. 7 1 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION URGING THE POSTMASTER 2 GENERAL TO ISSUE A COMMEMORATIVE POSTAGE 3 STAMP 4 2017 GENERAL SESSION 5 STATE OF UTAH 6 Chief Sponsor: Jani Iwamoto 7 House Sponsor: Dean Sanpei 8 Cosponsors: Lincoln Fillmore Ann Millner 9 J. Stuart Adams Wayne A. Harper Ralph Okerlund 10 Curtis S. Bramble Daniel Hemmert Brian E. Shiozawa 11 D. Gregg Buxton Deidre M. Henderson Jerry W. Stevenson 12 Jim Dabakis Lyle W. Hillyard Daniel W. Thatcher 13 Gene Davis David P. Hinkins Kevin T. Van Tassell 14 Margaret Dayton Don L. Ipson Evan J. Vickers 15 Luz Escamilla Karen Mayne 16 17 LONG TITLE 18 General Description: 19 This concurrent resolution urges the Postmaster General of the United States to issue a 20 commemorative postage stamp telling the inspiring story of the patriotic service of 21 Japanese Americans during World War II. 22 Highlighted Provisions: 23 This resolution: 24 < highlights the service of Japanese Americans during World War II; and 25 < urges the Postmaster General to issue a commemorative postage stamp that would 26 feature the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism. 27 Special Clauses: 28 None S.C.R. 7 Enrolled Copy 29 30 Be it resolved by the Legislature of the state of Utah, the Governor concurring therein: 31 WHEREAS, over 33,000 Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans), including 32 citizens of Utah, served with honor in the United States Army during World War II; 33 WHEREAS, as described in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, "race prejudice, war 34 hysteria, and a failure of -

III. Appellate Court Overturns Okubo-Yamada

III. appellate PACIFIC CrrlZEN court overturns Publication of the National Japanese American Citizens League Okubo-Yamada Vol. 86 No. 1 New Year Special: Jan. 6-13, 1978 20¢ Postpaid U.S. 15 Cents STOCKTON, Calif.-It was a go law firm of Baskin, festive Christmas for the Server and Berke. It is "ex Okubo and Yamada families tremely unlikely" the appel here upon hearing from late court would grant Hil their Chicago attorneys just ton Hotel a rehearing at the before the holidays that the appellate level nor receive Jr. Miss Pageant bars alien aspirants lllinois appellate court had permission to appeal to the SEATTLE-Pacific Northwest JACL leaders concede the "It would seem only right and proper that the pageant reversed the Cook County lllinois supreme court, fight to reinstate a 17-year-{)ld Vietnamese girl of Dayton, rules should be amended to include in their qualifications trial court decision and or Berke added. He said! Wash. who was denied the Touchet Valley Junior Miss dered the 1975 civil suit "The end result, after all of pageant candidates the words 'and aliens legally ad aeainst the Hilton Hotel title because she was not an American citizen has most these petitions, is that we are mitted as pennanent residents of the United States'," Ya Corp. to be reheard going to be given amthero~ likely been lost. mamoto wrote in a letter to the Spokane Spokesman Re The Okubo-Yamada case portunity to try this case or The state Junior Miss Pageant will be held at Wenat view. had alleged a breach of ex settle it before trial" chee Jan. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Righting an Injustice Or American Taliban? the Removal Of

Southern New Hampshire University Righting an Injustice or American Taliban? The Removal of Confederate Statues A Capstone Project Submitted to the College of Online and Continuing Education in Partial Fulfillment of the Master of Arts in History By Andreas Wolfgang Reif Manchester, New Hampshire July 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Andreas Wolfgang Reif All Rights Reserved ii Student: Andreas Wolfgang Reif I certify that this student has met the requirements for formatting the capstone project and that this project is suitable for preservation in the University Archive. July 12, 2018 __________________________________________ _______________ Southern New Hampshire University Date College of Online and Continuing Education iii Abstract In recent years, several racial instances have occurred in the United States that have reinvigorated and demanded action concerning Confederate flags, statues and symbology. The Charleston massacre in 2015 prompted South Carolina to finally remove the Confederate battle flag from state grounds. The Charlottesville riots in 2017 accelerated the removal of Confederate statues from the public square. However, the controversy has broadened the discussion of how the Civil War monuments are to be viewed, especially in the public square. Many of the monuments were not built immediately following the Civil War, but later, during the era of Jim Crow and the disenfranchisement of African Americans during segregation in the South. Are they tributes to heroes or are they relics of a racist past that sought not to remember as much as to intimidate and bolster white supremacy? This work seeks to break up the eras of Confederate monument building and demonstrate that different monuments were built at different times (and are still being built).