From Exclusion to Inclusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

The Effects of Private Memory on the Redress Movement of Japanese Americans

From Private Moments to Public Calls for Justice: The Effects of Private Memory on the Redress Movement of Japanese Americans A thesis submitted to the Department of History, Miami University, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Sarah Franklin Doran Miami University Oxford, Ohio May 201 ii ABSTRACT FROM PRIVATE MOMENTS TO PUBLIC CALLS FOR JUSTICE: THE EFFECTS OF PRIVVATE MEMORY ON THE REDRESS MOVEMENT OF JAPANESE AMERICANS Sarah Doran It has been 68 years since President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the internment of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans. This period of internment would shape the lives of all of those directly involved and have ramifications even four generations later. Due to the lack of communication between family members who were interned and their children, the movement for redress was not largely popular until the 1970s. Many families classified their time in the internment camps as subjects that were off limits, thus, leaving children without the true knowledge of their heritage. Because memories were not shared within the household, younger generations had no pressing reason to fight for redress. It was only after an opening in the avenue of communication between the generations that the search for true justice could commence. The purpose of this thesis is to explore how communication patterns within the home, the Japanese-American community, and ultimately the nation changed to allow for the successful completion of a reparation movement. What occurred to encourage those who were interned to end their silence and share their experiences with their children, grandchildren, and the greater community? Further, what external factors influenced this same phenomenon? The research for this project was largely accomplished through reading memoirs and historical monographs. -

Choose Your Words Describing the Japanese Experience During WWII

Choose your Words Describing the Japanese Experience During WWII Dee Anne Squire, Wasatch Range Writing Project Summary: Students will use discussion, critical thinking, viewing, research, and writing to study the topic of the Japanese Relocation during WWII. This lesson will focus on the words used to describe this event and the way those words influence opinions about the event. Objectives: • Students will be able to identify the impact of World War II on the Japanese in America. • Students will write arguments to support their claims based on valid reasoning and evidence. • Students will be able to interpret words and phrases within video clips and historical contexts. They will discuss the connotative and denotative meanings of words and how those word choices shaped the opinion of Americans about the Japanese immigrants in America. • Students will use point of view to shape the content and style of their writing. Context: Grades 7-12, with the depth of the discussion changing based on age and ability Materials: • Word strips on cardstock placed around the classroom • Internet access • Capability to show YouTube videos Time Span: Two to three 50-minute class periods depending on your choice of activities. Some time at home for students to do research is a possibility. Procedures: Day 1 1. Post the following words on cardstock strips throughout the room: Relocation, Evacuation, Forced Removal, Internees, Prisoners, Non-Aliens, Citizens, Concentration Camps, Assembly Centers, Pioneer Communities, Relocation Center, and Internment Camp. 2. Organize students into groups of three or four and have each group gather a few words from the walls. -

Full House Tv Show Episodes Free Online

Full house tv show episodes free online Full House This is a story about a sports broadcaster later turned morning talk show host Danny Tanner and his three little Episode 1: Our Very First Show.Watch Full House Season 1 · Season 7 · Season 1 · Season 2. Full House - Season 1 The series chronicles a widowed father's struggles of raising Episode Pilot Episode 1 - Pilot - Our Very First Show Episode 2 - Our. Full House - Season 1 The series chronicles a widowed father's struggles of raising his three young daughters with the help of his brother-in-law and his. Watch Full House Online: Watch full length episodes, video clips, highlights and more. FILTER BY SEASON. All (); Season 8 (24); Season 7 (24); Season. Full House - Season 8 The final season starts with Comet, the dog, running away. The Rippers no longer want Jesse in their band. D.J. ends a relationship with. EPISODES. Full House. S1 | E1 Our Very First Show. S1 | E1 Full House. Full House. S1 | E2 Our Very First Night. S1 | E2 Full House. Full House. S1 | E3 The. Watch Series Full House Online. This is a story about a sports Latest Episode: Season 8 Episode 24 Michelle Rides Again (2) (). Season 8. Watch full episodes of Full House and get the latest breaking news, exclusive videos and pictures, episode recaps and much more at. Full House - Season 5 Season 5 opens with Jesse and Becky learning that Becky is carrying twins; Michelle and Teddy scheming to couple Danny with their. Full House (). 8 Seasons available with subscription. -

Mapping Coils of Paranoia in a Neocolonial Security State

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2016 Becoming Serpent: Mapping Coils of Paranoia in a Neocolonial Security State Rachel J. Liebert Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1286 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BECOMING SERPENT: MAPPING COILS OF PARANOIA IN A NEOCOLONIAL SECURITY STATE By RACHEL JANE LIEBERT A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RACHEL JANE LIEBERT All Rights Reserved ii BECOMING SERPENT: MAPPING COILS OF PARANOIA IN A NEOCOLONIAL SECURITY STATE By RACHEL JANE LIEBERT This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Psychology to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Michelle Fine Date Chair of Examining Committee Maureen O’Connor Date Executive Officer Michelle Fine Sunil Bhatia Cindi Katz Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Becoming Serpent: Mapping Coils of Paranoia in a Neocolonial Security State By Rachel Jane Liebert Advisor: Michelle Fine What follows is a feminist, decolonial experiment to map the un/settling circulation of paranoia – how it is done, what it does, what it could do – within contemporary conditions of US white supremacy. -

Eleanor Roosevelt's Servant Leadership

Tabors: A Voice for the "Least of These:" Eleanor Roosevelt's Servant Le Servant Leadership: Theory & Practice Volume 5, Issue 1, 13-24 Spring 2018 A Voice for the “Least of These:” Eleanor Roosevelt’s Servant Leadership Christy Tabors, Hardin-Simmons University Abstract Greenleaf (2002/1977), the source of the term “servant leadership,” acknowledges a lack of nurturing or caring leaders in all types of modern organizations. Leaders and potential future leaders in today’s society need servant leader role-models they can study in order to develop their own servant leadership. In this paper, the author explores Eleanor Roosevelt’s life using Spears’ (2010) ten characteristics of servant leadership as an analytical lens and determines that Roosevelt functioned as a servant leader throughout her lifetime. The author argues that Eleanor Roosevelt’s servant leadership functions as a timeless model for leaders in modern society. Currently, a lack of literature exploring the direct link between Eleanor Roosevelt and servant leadership exists. The author hopes to fill in this gap and encourage others to contribute to this area of study further. Overall, this paper aims at providing practical information for leaders, particularly educational leaders, to utilize in their development of servant leadership, in addition to arguing why Eleanor Roosevelt serves as a model to study further in the field of servant leadership. Keywords: Servant Leadership, Leadership, Educational Leadership, Eleanor Roosevelt © 2018 D. Abbott Turner College of Business. SLTP. 5(1), 13-24 Published by CSU ePress, 2017 1 Servant Leadership: Theory & Practice, Vol. 5 [2017], Iss. 1, Art. 2 14 TABORS Eleanor Roosevelt, often remembered as Franklin D. -

Resources Available from Twin Cities JACL

CLASSROOM RESOURCES ON WORLD WAR II HISTORY AND THE JAPANESE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Available from the Twin Cities chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) (Updated September 2013) *Denotes new to our collection Contact: Sally Sudo, Twin Cities JACL, at [email protected] or (952) 835-7374 (days and evenings) SPEAKERS BUREAU Topics: Internment camps and Japanese American WWII soldiers Volunteer speakers are available to share with students their first-hand experiences in the internment camps and/or as Japanese American soldiers serving in the U.S. Army in the European or Pacific Theaters during World War II. (Note: limited to schools within the Twin Cities metropolitan area.) LIST OF RESOURCES Materials are available on loan for no charge Videocassette Tapes Beyond Barbed Wire - 88 min 1997, Mac and Ava Picture Productions, Monterey, CA Documentary. Personal accounts of the struggles that Japanese Americans faced when they volunteered or were drafted to fight in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II while their families were interned in American concentration camps. The Bracelet - 25 min 2001, UCLA Asian American Studies Center and the Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA Book on video. Presentation of the children’s book by Yoshiko Uchida about two friends separated by war. Second grader Emi is forced to move into an American concentration camp, and in the process she loses a treasured farewell gift from her best friend. Book illustrations are interwoven with rare home movie footage and historic photographs. Following the reading, a veteran teacher conducts a discussion and activities with a second grade class. -

(WALL NEWSPAPER PROJECT – Michelle) Examples of Investigative Journalism + Film

ANNEX II (WALL NEWSPAPER PROJECT – michelle) Examples of investigative journalism + film Best American Journalism of the 20th Century http://www.infoplease.com/ipea/A0777379.html The following works were chosen as the 20th century's best American journalism by a panel of experts assembled by the New York University school of journalism. 1. John Hersey: “Hiroshima,” The New Yorker, 1946 2. Rachel Carson: Silent Spring, book, 1962 3. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein: Investigation of the Watergate break-in, The Washington Post, 1972 4. Edward R. Murrow: Battle of Britain, CBS radio, 1940 5. Ida Tarbell: “The History of the Standard Oil Company,” McClure's, 1902–1904 6. Lincoln Steffens: “The Shame of the Cities,” McClure's, 1902–1904 7. John Reed: Ten Days That Shook the World, book, 1919 8. H. L. Mencken: Scopes “Monkey” trial, The Sun of Baltimore, 1925 9. Ernie Pyle: Reports from Europe and the Pacific during WWII, Scripps-Howard newspapers, 1940–45 10. Edward R. Murrow and Fred Friendly: Investigation of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, CBS, 1954 11. Edward R. Murrow, David Lowe, and Fred Friendly: documentary “Harvest of Shame,” CBS television, 1960 12. Seymour Hersh: Investigation of massacre by US soldiers at My Lai (Vietnam), Dispatch News Service, 1969 13. The New York Times: Publication of the Pentagon Papers, 1971 14. James Agee and Walker Evans: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, book, 1941 15. W. E. B. Du Bois: The Souls of Black Folk, collected articles, 1903 16. I. F. Stone: I. F. Stone's Weekly, 1953–67 17. Henry Hampton: “Eyes on the Prize,” documentary, 1987 18. -

Preserving and Interpreting World War Ii Japanese American Confinement Sites

Japanese American National Park Service Confinement Sites U.S. Department of the Interior Grant Program Winter 2014 / 2015 In this Nov. 2, 2011 photo, Speaker of the House John Boehner presents the Congressional Gold Medal to Japanese American veterans of World War II. At the ceremony were, from left, Mitsuo Hamasu (100th Infantry Battalion), Boehner, Susumu Ito (442), House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, Grant Ichikawa (MIS), and the late Sen. Daniel K. Inouye (442). A new Japanese American Confinement Sites grant (see page 11) will fund a Smithsonian Institution digital exhibition about the Congressional Gold Medal. Photo courtesy: KAREN BLEIER/AFP/Getty Images 2014: A YEAR IN REVIEW – PRESERVING AND INTERPRETING WORLD WAR II JAPANESE AMERICAN CONFINEMENT SITES The National Park Service (NPS) is pleased to report on the Over the past six years, the program has awarded 128 progress of the Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant grant awards totaling more than $15.3 million to private Program. On December 21, 2006, President George W. Bush nonprofit organizations, educational institutions, state, signed Public Law 109-441 (16 USC 461) – Preservation of local, and tribal governments, and other public entities. The Japanese American Confinement Sites – which authorized projects involve 19 states and the District of Columbia, and the NPS to create a grant program to encourage and include oral histories, preservation of camp artifacts and support the preservation and interpretation of historic buildings, documentaries and educational curriculum, and confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained. exhibits and memorials that preserve the confinement sites The law authorized up to $38 million for the life of the and honor the people incarcerated there by sharing their grant program. -

Thomas Byrne Edsall Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4d5nd2zb No online items Inventory of the Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Finding aid prepared by Aparna Mukherjee Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2015 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Thomas Byrne 88024 1 Edsall papers Title: Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Date (inclusive): 1965-2014 Collection Number: 88024 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 259 manuscript boxes, 8 oversize boxes.(113.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Writings, correspondence, notes, memoranda, poll data, statistics, printed matter, and photographs relating to American politics during the presidential administration of Ronald Reagan, especially with regard to campaign contributions and effects on income distribution; and to the gubernatorial administration of Michael Dukakis in Massachusetts, especially with regard to state economic policy, and the campaign of Michael Dukakis as the Democratic candidate for president of the United States in 1988; and to social conditions in the United States. Creator: Edsall, Thomas Byrne Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover -

Hawaii's Washington Place

HAWAII'S WASHINGTON PLACE ... VvASHINGTON PLi~\CE HONOLULU> HAWAII We hope you and the members of your org~nization 96813 will be able to join us on this evening espec1ally set aside in tribute to the memory of a magnificent monarch. August 12, 1982 Spouses are invited. Please forward the names of those who will attend to Mona Odachi at Washington Place, Honolulu, Hawaii 96813, by September 13. We look forward to welcoming you personally to Ms. Lorraine Freitas enjoy the home and the spirit of a Queen who holds a Queen Emma Hawaiian Civic Club special place in all of our hearts. 47-711 Kamehameha Highway Kaneohe, Hawaii 96744 A1aha pumehana s Dear Ms. Freitas: 9-~~()~ September marks the 144th birthday anniversary of Hawaii's beloved Queen Lili1uokalani. This year is a special one. The dedication of the Spirit of Lili'uokalani sculpture on the State Capitol concourse and the return of many of the Queen's personal belongings to Washington Place which now has been restored and refurbished are testaments to the enduring affection the people of Hawaii have for the Queen. More importantly, the spirit of the Queen continues to imbue a gracious aura to the walls and ard Kealoha gardens of Washington Place. ~~.~ Won't you come and share in a ho'okupu to the ~eV- _Rose Queen on September 23, from 7 to 9 p.m. Our evening ~~~ reception will feature a special exhibit of the Queen's memorabilia from the Bishop Mu~eum, items Ms. patri~. ~::d~: rarely on view to the public. We will also have music ~ Jl.-~ and light refreshments. -

DI CP19 F1 Ocrcombined.Pdf

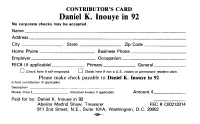

CONTRIBUTOR’S CARD Daniel K. Inouye in 92 No corporate checks may be accepted. Name ______________________________________________________________________ Address ____________________________________________________________________ C ity _________________ S ta te ___________________ Zip C ode __________________ Home Phone ________________________ Business Phone ________________________ Employer ____________________________ Occupation ___________________________ FEC# (if applicable) _____________ Primary ______________ General ______________ d l Check here if self-employed. CH Check here if not a U.S. citizen or permanent resident alien. Please make check payable to Daniel K. Inouye in 92 In-kind contribution (if applicable) Description ___________________________________________________ Market Price $ _____________________ (Attached invoice if applicable) Amount _$ ___________________ Paid for by: Daniel K. Inouye in 92 ______________ Abelina Madrid Shaw, Treasurer FEC # C00213314 911 2nd Street, N.E., Suite 101 A, Washington, D.C. 20002 This information is required of all contributions by the Federal Election Campaign Act. Corporation checks or funds, funds from government contractors and foreign nationals, and contributions made in the name of another cannot be accepted. Contributions or gifts to Daniel K. Inouye in 92 are not tax deductible. A copy of our report is on file with the Federal Election Commission and is available for purchase from the Federal Election Commission, Washington, D.C. 20463. JUN 18 '92 12=26 SEN. INOUYE CAMPAIGN 808 5911005 P.l 909 KAPIOLANI BOULEVARD HONOLULU, HAWAII 96814 (808) 591-VOTE (8683) 591-1005 (Fax) FACSIMILE TRANSMISSION TO; JENNIFER GOTO FAX#: NESTOR GARCIA FROM: KIMI UTO DATE; JUNE 1 8 , 1992 SUBJECT: CAMPAIGN WORKSHOP Number of pages Including this cover sheet: s Please contact K im i . at (808) 591-8683 if you have any problems with this transmission.