A History of Japanese American Internment Camps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utah Curriculum Units* * Download Other Enduring Community Units (Accessed September 3, 2009)

ENDURING COMMUNITIES Utah Curriculum Units* * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). Gift of the Nickerson Family, Japanese American National Museum (97.51.3) All requests to publish or reproduce images in this collection must be submitted to the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum. More information is available at http://www.janm.org/nrc/. 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 | Fax 213.625.1770 | janm.org | janmstore.com For project information, http://www.janm.org/projects/ec Enduring Communities Utah Curriculum Writing Team RaDon Andersen Jennifer Baker David Brimhall Jade Crown Sandra Early Shanna Futral Linda Oda Dave Seiter Photo by Motonobu Koizumi Project Managers Allyson Nakamoto Jane Nakasako Cheryl Toyama Enduring Communities is a partnership between the Japanese American National Museum, educators, community members, and five anchor institutions: Arizona State University’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program University of Colorado, Boulder University of New Mexico UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures Davis School District, Utah 369 East First Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 Tel 213.625.0414 Fax 213.625.1770 janm.org | janmstore.com Copyright © 2009 Japanese American National Museum UTAH Table of Contents 4 Project Overview of Enduring Communities: The Japanese American Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah Curricular Units* 5 Introduction to the Curricular Units 6 Topaz (Grade 4, 5, 6) Resources and References 34 Terminology and the Japanese American Experience 35 United States Confinement Sites for Japanese Americans During World War II 36 Japanese Americans in the Interior West: A Regional Perspective on the Enduring Nikkei Historical Experience in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Utah (and Beyond) 60 State Overview Essay and Timeline 66 Selected Bibliography Appendix 78 Project Teams 79 Acknowledgments 80 Project Supporters * Download other Enduring Community units (accessed September 3, 2009). -

A Participatory Study of the Self-Identity of Kibei Nisei Men: a Sub Group of Second Generation Japanese American Men William T

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 1993 A Participatory Study of the Self-Identity of Kibei Nisei Men: A Sub Group of Second Generation Japanese American Men William T. Masuda University of San Francisco Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Asian History Commons, Migration Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Masuda, William T., "A Participatory Study of the Self-Identity of Kibei Nisei Men: A Sub Group of Second Generation Japanese American Men" (1993). Doctoral Dissertations. 472. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/472 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The author of this thesis has agreed to make available to the University community and the public a copy of this thesis project. Unauthorized reproduction of any portion of this thesis is prohibited. The quality of this reproduction is contingent upon the quality of the original copy submitted. University of San Francisco Gleeson Library/Geschke Center 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117-1080 USA The University of San Francisco A PARTICIPATORY STUDY OF THE SELF-IDENTITY OF KIBEI NISEI MEN: A SUB GROUP OF SECOND GENERATION JAPANESE AMERICAN MEN A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty ofthe School ofEducation Counseling and Educational Psychology Program In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education by William T. -

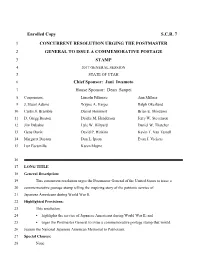

Enrolled Copy S.C.R. 7 1 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION

Enrolled Copy S.C.R. 7 1 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION URGING THE POSTMASTER 2 GENERAL TO ISSUE A COMMEMORATIVE POSTAGE 3 STAMP 4 2017 GENERAL SESSION 5 STATE OF UTAH 6 Chief Sponsor: Jani Iwamoto 7 House Sponsor: Dean Sanpei 8 Cosponsors: Lincoln Fillmore Ann Millner 9 J. Stuart Adams Wayne A. Harper Ralph Okerlund 10 Curtis S. Bramble Daniel Hemmert Brian E. Shiozawa 11 D. Gregg Buxton Deidre M. Henderson Jerry W. Stevenson 12 Jim Dabakis Lyle W. Hillyard Daniel W. Thatcher 13 Gene Davis David P. Hinkins Kevin T. Van Tassell 14 Margaret Dayton Don L. Ipson Evan J. Vickers 15 Luz Escamilla Karen Mayne 16 17 LONG TITLE 18 General Description: 19 This concurrent resolution urges the Postmaster General of the United States to issue a 20 commemorative postage stamp telling the inspiring story of the patriotic service of 21 Japanese Americans during World War II. 22 Highlighted Provisions: 23 This resolution: 24 < highlights the service of Japanese Americans during World War II; and 25 < urges the Postmaster General to issue a commemorative postage stamp that would 26 feature the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism. 27 Special Clauses: 28 None S.C.R. 7 Enrolled Copy 29 30 Be it resolved by the Legislature of the state of Utah, the Governor concurring therein: 31 WHEREAS, over 33,000 Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans), including 32 citizens of Utah, served with honor in the United States Army during World War II; 33 WHEREAS, as described in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, "race prejudice, war 34 hysteria, and a failure of -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05v6t6rn Author Kameyama, Eri Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Asian American Studies By Eri Kameyama 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Acts of Being and Belonging: Shin-Issei Transnational Identity Negotiations By Eri Kameyama Master of Arts in Asian American Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, Chair ABSTRACT: The recent census shows that one-third of those who identified as Japanese-American in California were foreign-born, signaling a new-wave of immigration from Japan that is changing the composition of contemporary Japanese-America. However, there is little or no academic research in English that addresses this new immigrant population, known as Shin-Issei. This paper investigates how Shin-Issei who live their lives in a complex space between the two nation-states of Japan and the U.S. negotiate their ethnic identity by looking at how these newcomers find a sense of belonging in Southern California in racial, social, and legal terms. Through an ethnographic approach of in-depth interviews and participant observation with six individuals, this case-study expands the available literature on transnationalism by exploring how Shin-Issei negotiations of identities rely on a transnational understandings of national ideologies of belonging which is a less direct form of transnationalism and is a more psychological, symbolic, and emotional reconciliation of self, encompassed between two worlds. -

Expanding the Crime of Genocide to Include Ethnic Cleansing: a Return to Established Principles in Light of Contemporary Interpretations

Expanding the Crime of Genocide to Include Ethnic Cleansing: A Return to Established Principles in Light of Contemporary Interpretations Micol Sirkin† “‘The only alternative to ethnic minorities is ethnically pure states created by slaughter or expulsion.’”1 I. INTRODUCTION It may be surprising to discover that ethnic cleansing is legally dis- tinct from genocide considering that the media use these terms inter- changeably.2 Currently, no formal legal definition of ethnic cleansing exists.3 In characterizing the acts of the Yugoslav war, however, the United Nations Security Council’s Commission of Experts on violations of humanitarian law stated that “‘ethnic cleansing’ means rendering an area ethnically homogenous by using force or intimidation to remove † J.D. Candidate, Seattle University School of Law, 2010; B.A., Philosophy, Boston University, 2006. I would like to thank Professor Ronald C. Slye for his insight and guidance. I would also like to thank K.D. Babitsky, Lindsay Noel, and Alexis Toma for their hard work and friendship. Last, but not least, I would like to thank my mother, Dalia Sirkin, for always raising the bar and believing in me every step of the way. 1. Jean-Marie Henckaerts, Mass Expulsion in Modern International Law and Practice, in 41 INT’L STUD. IN HUM. RTS. 1, 108 (1995) (quoting Fearful Name from a Nazi Past, L.A. TIMES, June 22, 1994, at B6) (emphasis added). 2. See, e.g., Andy Segal, ‘Bombs for Peace’ After Slaughter in Bosnia, CNN, Dec. 4, 2004, http://www.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/europe/11/20/sbm.bosnia.holbrooke/ (“Three years later, [Ri- chard Holbrooke] would become one of the most influential U.S. -

Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: the Tule Lake Pilgrimage

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 6-9-2016 "Yes, No, Maybe": Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: The uleT Lake Pilgrimage Ella-Kari Loftfield Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Loftfield, Ella-Kari. ""Yes, No, Maybe": Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: The uleT Lake Pilgrimage." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ella-Kari Loftfield Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Professor Melissa Bokovoy, Chairperson Professor Jason Scott Smith Professor Barbara Reyes i “YES, NO, MAYBE−” LOYALTY AND BETRAYAL RECONSIDERED: THE TULE LAKE PILGRIMAGE By Ella-Kari Loftfield B.A., Social Anthropology, Haverford College, 1985 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2016 ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my father, Robert Loftfield whose enthusiasm for learning and scholarship knew no bounds. iii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people. Thanks to Peter Reed who has been by my side and kept me well fed during the entire experience. Thanks to the Japanese American National Museum for inviting me to participate in curriculum writing that lit a fire in my belly. -

World War Ii Internment Camp Survivors

WORLD WAR II INTERNMENT CAMP SURVIVORS: THE STORIES AND LIFE EXPERIENCES OF JAPANESE AMERICAN WOMEN Precious Vida Yamaguchi A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Ph.D., Advisor Sherlon Pack-Brown, Ph.D. Graduate Faculty Representative Lynda D. Dixon, Ph.D. Lousia Ha, Ph.D. Ellen Gorsevski, Ph.D. © 2010 Precious Vida Yamaguchi All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 required all people of Japanese ancestry in America (one-eighth of Japanese blood or more), living on the west coast to be relocated into internment camps. Over 120,000 people were forced to leave their homes, businesses, and all their belongings except for one suitcase and were placed in barbed-wire internment camps patrolled by armed police. This study looks at narratives, stories, and experiences of Japanese American women who experienced the World War II internment camps through an anti-colonial theoretical framework and ethnographic methods. The use of ethnographic methods and interviews with the generation of Japanese American women who experienced part of their lives in the United State World War II internment camps explores how it affected their lives during and after World War II. The researcher of this study hopes to learn how Japanese American women reflect upon and describe their lives before, during, and after the internment camps, document the narratives of the Japanese American women who were imprisoned in the internment camps, and research how their experiences have been told to their children and grandchildren. -

Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africaâ•Žs

Journal of Dispute Resolution Volume 2019 Issue 1 Article 16 2019 Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Benjamin Zinkel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation Benjamin Zinkel, Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation, 2019 J. Disp. Resol. (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr/vol2019/iss1/16 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Dispute Resolution by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zinkel: Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africa’s Truth Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Benjamin Zinkel* I. INTRODUCTION South Africa and the United States are separated geographically, ethnically, and culturally. On the surface, these two nations appear very different. Both na- tions are separated by nearly 9,000 miles1, South Africa is a new democracy, while the United States was established over two hundred years2 ago, the two nations have very different climates, and the United States is much larger both in population and geography.3 However, South Africa and the United States share similar origins and histories. Both nations have culturally and ethnically diverse populations. Both South Africa and the United States were founded by colonists, and both nations instituted slavery.4 In the twentieth century, both nations discriminated against non- white citizens. -

Crystal City Family Internment Camp Brochure

CRYSTAL CITY FAMILY INTERNMENT CAMP Enemy Alien Internment in Texas CRYSTAL CITY FAMILY during World War II INTERNMENT CAMP Enemy Alien Internment in Texas Acknowledgements during World War II The Texas Historical Commission (THC) would like to thank the City of Crystal City, the Crystal City Independent School District, former Japanese, German, and Italian American and Latin American internees and their families and friends, as well as a host of historians who have helped with the preparation of this project. For more information on how to support the THC’s military history program, visit thcfriends.org/donate. This project is assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the THC and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION 08/20 “Inevitably, war creates situations which Americans would not countenance in times of peace, such as the internment of men and women who were considered potentially dangerous to America’s national security.” —INS, Department of Justice, 1946 Report Shocked by the December 7, 1941, Empire came from United States Code, Title 50, Section 21, of Japan attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii that Restraint, Regulation, and Removal, which allowed propelled the United States into World War II, one for the arrest and detention of Enemy Aliens during government response to the war was the incarceration war. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Proclamation of thousands No. 2525 on December 7, 1941 and Proclamations No. -

The Mass Internment of Uyghurs: “We Want to Be Respected As Humans

The Mass Internment of Uyghurs: “We want to be respected as humans. Is it too much to ask?” TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY.....................................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND.............................................................................................................................5 The Re-education Campaign Emerges from “De-extremification”……………………………….6 The Scale and Nature of the Current Internment Camp System…………………………………10 Reactions to the Internment Camps…………………………………………………...................17 VOICES OF THE CAMPS ...........................................................................................................19 “Every night I heard crying” .........................................................................................................19 “I am here to break the silence”.....................................................................................................20 “He bashed his head against a wall to try to kill himself”.............................................................23 LEGAL INSTRUMENTS .............................................................................................................38 RECOMMENDATIONS...............................................................................................................41 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................43 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...........................................................................................................43 -

Look Toward the Mountain, Episode 6 Transcript

LOOK TOWARD THE MOUNTAIN, EPISODE 6 TRANSCRIPT ROB BUSCHER: Welcome to Look Toward the Mountain: Stories from Heart Mountain Incarceration Camp, a podcast series about life inside the Heart Mountain Japanese American Relocation Center in northwestern Wyoming during World War II. I’m your host, Rob Buscher. This podcast is presented by the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and is funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. ROB BUSCHER: The sixth episode titled “Organizing Resistance” will explore how the Japanese American tradition of organizing evolved in camp to become a powerful resistance movement that dominated much of the Heart Mountain experience in its later years. INTRO THEME ROB BUSCHER: For much of history, Japanese traditional society was governed by the will of its powerful military warlords. Although in principle the shogun and his vassal daimyo ruled by force, much of daily life within the clearly delineated class system of Japanese society relied on consensus-building and mutual accountability. Similar to European Feudalism, the Japanese Han system created a strict hierarchy that privileged the high-born samurai class over the more populous peasantry who made up nearly 95% of the total population. Despite their low rank, food-producing peasants were considered of higher status than the merchant class, who were perceived to only benefit themselves. ROB BUSCHER: During the Edo period, peasants were organized into Gonin-gumi - groups of five households who were held mutually accountable for their share of village taxes, which were paid from a portion of the food they produced. If their gonin-gumi did not meet their production quota, all the peasants in their group would be punished. -

Unsuspecting

UNSUSPECTING DAVID SCHRAUB* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 362 I. SUSPECT STASIS .................................................................................. 366 A. The Indicia of Suspectness ........................................................... 367 B. The Indicia’s Impermanence ....................................................... 372 1. The Carolene Factors ............................................................ 372 2. The Rodriguez Factors ........................................................... 376 3. Immutability and Irrelevancy ................................................ 378 a. Immutability .................................................................... 378 b. Irrelevancy ...................................................................... 381 II. TRANSIENT IN THEORY, CONCRETE IN FACT: WHY HAVEN’T CLASSES BEEN UNSUSPECTED? ........................................................... 383 A. Lack of Opportunity ..................................................................... 384 B. Lack of Incentive .......................................................................... 389 C. Lack of Clarity ............................................................................. 393 III. AGAINST PERPETUAL SUSPECT CLASSES ............................................ 396 A. Democratic Tensions ................................................................... 396 B. Suspect Classification as Zero-Sum ...........................................