This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Balcarras Sixth Form 2021

Balcarras Sixth Form 2021 Teddy Holbrook Aiden Cheal (Year 11 Balcarras) (Year 11 Winchcombe) AS: AABB AS: BCCC Plans: to study Geography Plans: to study Architecture with Environmental Throughout my time at Balcarras I have always felt comfortable, Engineering informed and understood. For me, such support is essential Joining Balcarras 6th Form from Winchcombe School was quite daunting to progressing in my academic work, and the sixth form team with new subjects, new teachers and new classmates, but the school and my teachers have always created a fantastic learning was really welcoming right from the start. The school offers a wide range environment which has helped me to work to the best of my of extra-curricular activities which allowed new students, like me, to abilities. I was also attracted by the opportunity of studying 4 interact with those who had been at the school from Year 11. The music subjects in Year 12, and continuing with geography, economics department played a key role in this as many students, myself included, and English Literature in Year 13. The change from Year 12 to Year were encouraged to perform and work with students already at the school 13 gave me more time to discover my interests and a broader in many events such as the House Music and the production of “We Will range of knowledge to use in further education. Additionally, Rock You”. The early events in the year helped to break the ice as many the completion of an extended project qualification has helped of us found ourselves comfortably settled in within the first few weeks. -

Strategic Review of Secondary Education Planning for Cheltenham

Strategic review of Secondary Education Planning for Cheltenham January 2017 1 Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Supporting data .................................................................................................................................. 3 Current number on roll ....................................................................................................................... 3 Pupil forecasts 2015/16 ...................................................................................................................... 4 Planned local housing developments ................................................................................................. 4 Strategic Housing ................................................................................................................................ 5 Recommendation, Land and Footnotes....………………………………………………………………………………………6 Executive Summary There has been pressure on local primary school places in Cheltenham since 2011. This is the result of a change in the birth rate locally and natural changing demographics, coupled with some local housing growth. This growth has been significant and resulted in the need to provide additional temporary and permanent school places at existing primary schools. -

Secondary School and Academy Admissions

Secondary School and Academy Admissions INFORMATION BOOKLET 2021/2022 For children born between 1st September 2009 and 31st August 2010 Page 1 Schools Information Admission number and previous applications This is the total number of pupils that the school can admit into Year 7. We have also included the total number of pupils in the school so you can gauge its size. You’ll see how oversubscribed a school is by how many parents had named a school as one of their five preferences on their application form and how many of these had placed it as their first preference. Catchment area Some comprehensive schools have a catchment area consisting of parishes, district or county boundaries. Some schools will give priority for admission to those children living within their catchment area. If you live in Gloucestershire and are over 3 miles from your child’s catchment school they may be entitled to school transport provided by the Local Authority. Oversubscription criteria If a school receives more preferences than places available, the admission authority will place all children in the order in which they could be considered for a place. This will strictly follow the priority order of their oversubscription criteria. Please follow the below link to find the statistics for how many pupils were allocated under the admissions criteria for each school - https://www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/education-and-learning/school-admissions-scheme-criteria- and-protocol/allocation-day-statistics-for-gloucestershire-schools/. We can’t guarantee your child will be offered one of their preferred schools, but they will have a stronger chance if they meet higher priorities in the criteria. -

Secondary Allocation Day 2021 V3.Xlsx

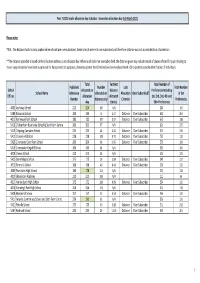

Year 7 2021 intake allocation day statistics - Secondary allocation day 1st March 2021 Please note: *N/A - The distance factor is only applied when schools are oversubscribed, these schools were not oversubscribed and therefore distance was not a consideration of admission. **The distance provided is based on the allocation address as at allocation day. Where a school is not oversubscribed, the distance given may include details of places offered for pupils hoping to move. Large distances have been suppressed for data protection purposes, distances greater that 20 miles have been replaced with >20 to protect possible identification of individuals. Total Furthest Total Number of Published Number Last Total Number School allocated on distance Preferences Including School Name Admission allocated on Allocation Over Subscribed? of 1st DfE no. allocation allocated 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and Number distance only Criterion Preferences day (miles) 5th+ Preferences 4032 Archway School 215 214 100 N/A 280 109 5408 Balcarras School 194 194 8 1.47 Distance Over Subscribed 602 204 4012 Barnwood Park School 180 180 107 0.97 Distance Over Subscribed 678 238 5418 Cheltenham Bournside School & Sixth Form Centre 300 300 97 N/A 620 225 5414 Chipping Campden School 225 225 46 5.62 Distance Over Subscribed 353 219 5412 Chosen Hill School 228 228 138 9.50 Distance Over Subscribed 737 115 5420 Cirencester Deer Park School 209 209 96 10.67 Distance Over Subscribed 576 182 5419 Cirencester Kingshill School 196 196 64 N/A 303 166 4024 Cleeve School 310 310 94 N/A -

Cheltenham Children's Needs Assessment 2018

Cheltenham Children’s Needs Assessment 2018 Data & Analysis Team Gloucestershire County Council [email protected] 2 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Overall picture............................................................................................................................. 4 3. Demographics and deprivation ................................................................................................... 4 Population ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Poverty and deprivation ................................................................................................................. 5 House prices and affordability ...................................................................................................... 10 Ethnicity ........................................................................................................................................ 13 4. Educational achievement .......................................................................................................... 22 End of EYFS .................................................................................................................................... 24 KS2 ................................................................................................................................................ -

241 Cirencester Road Charlton Kings W Cheltenham W Gloucestershire W Gl53 8Eb 241 Cirencester Road

241 CIRENCESTER ROAD charlton kings w cheltenham w gloucestershire w gl53 8eb 241 CIRENCESTER ROAD charlton kings w cheltenham w gloucestershire w gl53 8eb A WONDERFUL RENOVATED AND EXTENDED PERIOD SEMI-DETACHED PROPERTY WITH A FABULOUS CONTEMPORARY EXTENSION WITH BIFOLD DOORS, IN THE BALCARRAS SCHOOL CATCHMENT AREA Entrance porch w entrance hall w sitting room w snug w study w utility room w cloakroom w open plan living/dining/kitchen w master bedroom with en suite shower room w three further double bedrooms w family bathroom Good sized rear garden with wide patio w 229 square foot outbuilding currently used as a summer house/ occasional guest accommodation and tool shed w gravelled parking to the front In addition, on the ground floor, are two further reception situation rooms, including a working fireplace, a study, a fitted utility / Charlton Kings is an incredibly sought-after residential district boot room, and a cloakroom. The recent downstairs side and located to the south of Cheltenham town centre, with excellent rear extension includes underfloor heating throughout. access to the town itself and local facilities. There are four double bedrooms, including a master bedroom 241 Cirencester Road is located on the edge of Charlton Kings with new en suite shower room, and a recently installed family but well within effective catchment for Balcarras School and a bathroom serving the remaining three bedrooms. short walk to Timbercombe Wood, Hotel Gym and Sainsbury’s Local. There is an unusually large and private garden to the rear, mostly laid to lawn but with a wide patio immediately Cheltenham is famed as one of the most complete Regency to the rear of the house. -

View Or Download a Copy of Amy and Margaret's Presentation Slides

Thread Counts Love Your Uniform Take 2 1 Working in Partnership School of Arts and School of Education and Cheltenham Education Partnership (CEP): Humanities Schools involved • All Saints Academy • Balcarras School • Cheltenham Bournside • Cleeve School • Cheltenham Ladies College • Cheltenham College Vice Chancellor and Principal of Cheltenham Ladies • Dean Close College • Pittville School • St Edwards • Winchcombe School 2 Thread Counts Student brief: brings to life the principles experienced through the Education for Sustainability focus of their curriculum. 3 Thread Counts: ‘Love Your Uniforms’ Project brief: challenge pupils to design and make wearable fashion items from used/second hand school uniform shirts. 4 Intended Outcomes • The target audience: 14-18 year olds from CEP schools, who are passionate about fashion and/or sustainability. • Professional context: the project will run across 3 days within the Fashion Design studios. • Knowledge building: fashion consumption, the impact fashion has on the environment and an understanding of a life cycle of a school uniform. • Skills development: up cycling and/or repurposing school uniforms, team work, leadership, creativity, technical sewing and drawing skills. • Cross course and cross generational collaborative experience to support professional development. 5 Project Delivery The three days in June will consist of hosting 2-4 students from a range of the CEP schools. Day one will consist of providing an overview of the challenges of sustainability in fashion, setting the design brief, delivering workshops on drawing and sewing, and finally, enabling the students to design a solution to the design brief. Day two will allow the students to design and make their garment/product, based on the design brief. -

Cheltenham Places Update

School Place Planning in Cheltenham th 28 September 2018 Cheltenham Secondary Schools Demographics - Medium term trends in pupil numbers 55,000 50,000 45,000 40,000 Primary Pupil Numbers 35,000 Secondary Pupil Numbers Pupil NumbersPupil 30,000 25,000 20,000 The Cheltenham Dilemma • By 2019/20 all Cheltenham Secondary schools will be full, with around 150 children without a school place, equivalent to 5 forms of entry. • By 2021/22 this will have increased to around 200 children without places each year, equivalent to 7 forms of entry. Current Year 7 Intake Forecast 1250 1200 1150 1100 Year 7 Capacity - Published 1050 Admission Number (PAN) Basic need + Additional places 1000 including housing 950 Numberof pupils/ places 900 850 16/17 17/18 18/19 19/20 20/21 21/22 22/23 23/24 24/25 Year 7 Intake Forecast with new 6FE School 1250 1200 1150 1100 Year 7 Capacity - Published 1050 Admission Number (PAN) Basic need + Additional places 1000 including housing 950 Numberof pupils/ places 900 850 16/17 17/18 18/19 19/20 20/21 21/22 22/23 23/24 24/25 What’s Impacting on School Places? • Upward trend in the birth rate • Pupil yield from non-strategic housing • Pupil yield from strategic housing (Joint Core Strategy) - A5 – North West Cheltenham (Uckington) - A6 – South Cheltenham Leckhampton (Farm Lane element) - Safeguarded Land West Cheltenham – Hester’s Way/Springbank - Not including pupil yield arising from future Leckhampton developments (e.g. Miller, David Wilson Homes etc) 2018 Cheltenham Planning Area Forecasts Cheltenham Education Planning -

Balcarras Sixth Form

2019 Balcarras Sixth Form Alice Twine Sophie Wheeler (Year 11 Winchcombe School) (Year 11 Balcarras) AS: AABC AS: AACC Plans: to take a gap year before getting an Plans: to study business management at Bristol apprenticeship as a researcher in a media company. University. The positive atmosphere, the great relationship between Continuing my studies here at Balcarras was the obvious option teachers and students and the academic results, made for me, due to my experiences with the focussed yet encouraging Balcarras my first choice for sixth form, a decision I don’t environment, I learned of in lower school. Balcarras offers regret. When I first joined Balcarras in Year 12, I did not an opportunity for independent study alongside high quality know what I wanted to do after, but through help from teaching which allows students to reach their full potential. my teachers and a wide variety of post-sixth form options The sixth form provides a broad variety of extracurricular provided by external speakers, I have now become drawn to opportunities for all students; a highlight for me was being a the idea of journalism and am aware of possible routes to part of the Young Enterprise team. I enjoyed every moment of become one, information I did not know before. Before sixth the process, and it gave me a great insight into the day to day form, I was set on the belief that I would go to university life of running a business. Having created a product that we yet Balcarras has showed me that there are plenty of were passionate about, it motivated us to work really hard. -

Glenfall News ...A Newsletter to Inform the School Community About the Day to Day Life of Our School

Glenfall News ...a newsletter to inform the school community about the day to day life of our school. Friday 2nd October 2015 A word from the head....... With such a fantastic week of weather it has felt just like summer again, actually its been much better than most of the summer holidays. It has been great to see the children still using the field and making the most of 100 Club. You should have received letters and the Autumn sunshine, long may it continue!! application forms for Glenfall’s 100 club in book bags this week. Last year we raised over £500 from our 100 Last weekend a group of children and staff took part in club, and had many happy prize winners over the year. The Cheltenham Half Marathon Schools Challenge. Mrs Full details will be in next week’s letter. Please Nye, Miss Clapham and Miss Kelly ran with the children complete your forms and return to the school office as in a pacey race. Congratulations to Ivor Northup who soon as possible. Good Luck! Balcarras School Cookery Course for Y5 & Y6 Do you enjoy cooking or would you like to get better at cooking? Balcarras School will be running the after school cookery courses again this year for pupils in years 5 and 6 attending specific local came in 8th position with a time of just over five junior schools. minutes. Well done to all of the competitors. Thank you to Mrs Whyte for organising the event and for training Each week you will learn new skills and have the children to run their miles in the run up to the race. -

Download/Downloads/Id/3076/Leckhampton Landscape a Nd Visual Appraisal.Pdf

Leckhampton with Warden Hill Parish Council - Response to the Inspector’s Questions Leckhampton with Warden Hill Parish Council Cheltenham Local Plan Examination: Submission in response to the Inspector’s Questions Matter 3: Question 6 – Is there adequate justification for the siting of a school within the Leckhampton allocation (MD5)? Over the past decade shortages of secondary school places have forced some students to travel long distances to other schools. This particularly affects families living in Charlton Park between Leckhampton and Charlton Kings. Balcarras and Bournside schools both operate catchments. Originally these covered the whole area between the schools. But Balcarras has become very popular. Many parents move into Charlton Kings to secure places at Balcarras for their children, some moving temporarily and exploiting the sibling rule. Balcarras has recently discontinued its sibling rule, but nevertheless, according to GCC, the catchment radius of Balcarras is as little as 0.8-0.5 miles. Bournside and Balcarras have both expanded but major housing development in Up Hatherley has taken up extra Bournside capacity. So there is now a large gap between the catchments. According to GCC, young families are moving into Leckhampton and Warden Hill, changing the demography. Also, some parents in north Cheltenham prefer to send their children to schools in south Cheltenham and this adds to demand for both primary and secondary places. To meet this, Leckhampton Primary School is being expanded from 420 pupils to 630 and Warden Hill Primary will probably expand likewise. The need for a new secondary school in south Cheltenham was not raised in the JCS; it materialised only in December 2017. -

Assessment of Cheltenham Schools

CHELTENHAM SECONDARY SCHOOL EXPANSION ASSESSMENT TO MEET ADDITIONAL NEED There are five secondary schools in the Cheltenham school planning area. Pate’s Grammar School (11-18 school) and All Saints’ Academy (11-18 school) are situated in the north of Cheltenham, Cheltenham Bournside (11-18 school) and Balcarras (11-18 school) located in the south and Pittville (11-16 school) situated to the west. In the autumn of 2016 a strategic review of school place planning in Cheltenham was undertaken to build an overall picture of the current and future pattern of need for places. Taking into account basic need projections, increases to existing school capacity and the known new housing developments, including the provision of a new secondary school to serve the North West Cheltenham development, there will be a shortfall of at least 6 forms of entry by 2021/22; this is equivalent to a shortage of 180 year 7 secondary school places each year. Since 2011 it has been possible to meet the rising demand for primary places by working collaboratively with schools in the primary sector to increase their published admission number (PAN). More recently, by working with Secondary schools, it has been possible to provide additional capacity as these pupils move into the secondary sector. On 1st February 2017, Council officers met with all Cheltenham Secondary Headteachers to share this information and consider options going forward. Whilst some schools were happy to consider permanent expansion, an assessment of each site demonstrated that the continued expansion of existing secondary provision is not a viable option to meet the additional need in full.