Library Trends V.55, No.3 Winter 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust Glossary

Holocaust Glossary A ● Allies: 26 nations led by Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union that opposed Germany, Italy, and Japan (known as the Axis powers) in World War II. ● Antisemitism: Hostility toward or hatred of Jews as a religious or ethnic group, often accompanied by social, economic, or political discrimination. (USHMM) ● Appellplatz: German word for the roll call square where prisoners were forced to assemble. (USHMM) ● Arbeit Macht Frei: “Work makes you free” is emblazoned on the gates at Auschwitz and was intended to deceive prisoners about the camp’s function (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Aryan: Term used in Nazi Germany to refer to non-Jewish and non-Gypsy Caucasians. Northern Europeans with especially “Nordic” features such as blonde hair and blue eyes were considered by so-called race scientists to be the most superior of Aryans, members of a “master race.” (USHMM) ● Auschwitz: The largest Nazi concentration camp/death camp complex, located 37 miles west of Krakow, Poland. The Auschwitz main camp (Auschwitz I) was established in 1940. In 1942, a killing center was established at Auschwitz-Birkenau (Auschwitz II). In 1941, Auschwitz-Monowitz (Auschwitz III) was established as a forced-labor camp. More than 100 subcamps and labor detachments were administratively connected to Auschwitz III. (USHMM) Pictured right: Auschwitz I. B ● Babi Yar: A ravine near Kiev where almost 34,000 Jews were killed by German soldiers in two days in September 1941 (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Barrack: The building in which camp prisoners lived. The material, size, and conditions of the structures varied from camp to camp. -

![Cultural Life in the Theresienstadt Ghetto- Dr. Margalit Shlain [Posted on Jan 5Th, 2015] People Carry Their Culture with Them W](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3476/cultural-life-in-the-theresienstadt-ghetto-dr-margalit-shlain-posted-on-jan-5th-2015-people-carry-their-culture-with-them-w-673476.webp)

Cultural Life in the Theresienstadt Ghetto- Dr. Margalit Shlain [Posted on Jan 5Th, 2015] People Carry Their Culture with Them W

Cultural Life in the Theresienstadt Ghetto- Dr. Margalit Shlain [posted on Jan 5th, 2015] People carry their culture with them wherever they go. Therefore, when the last Jewish communities in Central Europe were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto (Terezin in Czech), they created a cultural blossoming in the midst of destruction, at their last stop before annihilation. The paradoxical consequence of this cultural flourishing, both in the collective memory of the Holocaust era and, to a certain extent even today, is that of an image of the Theresienstadt ghetto as having had reasonable living conditions, corresponding to the image that the German propaganda machine sought to present. The Theresienstadt ghetto was established in the north-western part of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia on November 24, 1941. It was allegedly to be a "Jewish town" for the Protectorate’s Jews, but was in fact a Concentration and Transit Camp, which functioned until its liberation on May 8, 1945. At its peak (September 1942) the ghetto held 58,491 prisoners. Over a period of three and a half years, approximately 158,000 Jews, from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Germany, Austria, Holland, Denmark, Slovakia, and Hungary, as well as evacuees from other concentration camps, were transferred to it. Of these, 88,129 were sent on to their death in the 'East', of whom only 4,134 survived. In Theresienstadt itself 35,409 died from "natural" causes like illness and hunger, and approximately 30,000 inmates were liberated in the ghetto. This ghetto had a special character, as the Germans had intended to turn it into a ghetto for elderly and privileged German Jews, according to Reinhard Heydrich’s announcement at the "Wannsee Conference" which took place on January 20th, 1942 in Berlin. -

STUDENT HANDOUT the Ghettos

THE GHETTOS Invasion of Poland In September 1939, the Germans invaded Poland. Poland lost its independence, and its citizens were subjected to severe oppression. Schools were closed, all political activity was banned, and many members of the Polish elite, intellectuals, political leaders, and clerics, were sent to concentration camps or murdered immediately. Jews were subjected to violence, humiliation, dispossession, and arbitrary kidnappings for forced labor by German soldiers Jews rounded up for forced labor, Przemysl, Poland, who abused Jews in the streets, paying special October 1939. Yad Vashem Photo Archive (5323) L4 attention to religious Jews. Many thousands of Poles and Jews were murdered in the first them great control over the Jews. Soon after months of the occupation, not yet as a policy of the ghettos began to be established, the Nazis THEsystematic GHETTOS mass murder, but an expression of tried to remove the Jews from their midst the brutal nature of the occupying forces. through population transfer. At first they sought to drive Jews into Soviet territory, but On September 21, 1939, just after the German when that strategy proved unworkable, the conquest of Poland, Reinhard Heydrich, Nazis developed a plan to send the Jews to the Nazi head of the SIPO (security police) and island of Madagascar. This plan also proved SD (security service) issued an order to the INTRODUCTIONcommanders in occupied Poland. The first, immediate stage called for several practical During the Holocaust, “ghettos” were places of SECRET measures, including deporting Jews from imprisonmentwestern that and became central deadly Poland for the and Jews concentrating as a Berlin: September 21, 1939 direct resultthem of Nazi in the policies. -

Downloads/.Last Accessed: 9

Tracing and Documenting Nazi Victims Past and Present Arolsen Research Series Edited by the Arolsen Archives – International Center on Nazi Persecution Volume 1 Tracing and Documenting Nazi Victims Past and Present Edited by Henning Borggräfe, Christian Höschler and Isabel Panek On behalf of the Arolsen Archives. The Arolsen Archives are funded by the German Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media (BKM). ISBN 978-3-11-066160-6 eBook (PDF) ISBN 978-3-11-066537-6 eBook (EPUB) ISBN 978-3-11-066165-1 ISSN 2699-7312 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licens-es/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020932561 Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020 by the Arolsen Archives, Henning Borggräfe, Christian Höschler, and Isabel Panek, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: Jan-Eric Stephan Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Preface Tracing and documenting the victims of National Socialist persecution is atopic that has receivedlittle attention from historicalresearch so far.Inorder to take stock of existing knowledge and provide impetus for historicalresearch on this issue, the Arolsen Archives (formerlyknown as the International Tracing Service) organized an international conferenceonTracing and Documenting Victimsof Nazi Persecution: Historyofthe International Tracing Service (ITS) in Context. Held on October 8and 92018 in BadArolsen,Germany, this event also marked the seventieth anniversary of search bureaus from various European statesmeet- ing with the recentlyestablished International Tracing Service (ITS) in Arolsen, Germany, in the autumn of 1948. -

Study Guide REFUGE

A Guide for Educators to the Film REFUGE: Stories of the Selfhelp Home Prepared by Dr. Elliot Lefkovitz This publication was generously funded by the Selfhelp Foundation. © 2013 Bensinger Global Media. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements p. i Introduction to the study guide pp. ii-v Horst Abraham’s story Introduction-Kristallnacht pp. 1-8 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 8-9 Learning Activities pp. 9-10 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Kristallnacht pp. 11-18 Enrichment Activities Focusing on the Response of the Outside World pp. 18-24 and the Shanghai Ghetto Horst Abraham’s Timeline pp. 24-32 Maps-German and Austrian Refugees in Shanghai p. 32 Marietta Ryba’s Story Introduction-The Kindertransport pp. 33-39 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 39 Learning Activities pp. 39-40 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Sir Nicholas Winton, Other Holocaust pp. 41-46 Rescuers and Rescue Efforts During the Holocaust Marietta Ryba’s Timeline pp. 46-49 Maps-Kindertransport travel routes p. 49 2 Hannah Messinger’s Story Introduction-Theresienstadt pp. 50-58 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 58-59 Learning Activities pp. 59-62 Enrichment Activities Focusing on The Holocaust in Czechoslovakia pp. 62-64 Hannah Messinger’s Timeline pp. 65-68 Maps-The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia p. 68 Edith Stern’s Story Introduction-Auschwitz pp. 69-77 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 77 Learning Activities pp. 78-80 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Theresienstadt pp. 80-83 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Auschwitz pp. 83-86 Edith Stern’s Timeline pp. -

Atrocity Film Abstract Keywords Full Text

HOME ABOUT LOGIN CURRENT ISSUE PAST ISSUES ANNOUNCEMENTS BOARD OPEN APPARATUS BOOKS Home > No 12 (2021) > Schmidt Atrocity Film Fabian Schmidt, Alexander Oliver Zöller Abstract What if the SS as the main Nazi organisation responsible for the Holocaust produced a secret !lm about the persecution and murder of the European Jews during World War 2? The essay discusses the possible production of a documentary !lm about the genocide, made by the perpetrators. In doing so, it challenges a set of assumptions that is commonly put into action against such an endeavour. By examining the various activities of private and o"cial photographers and cameramen in the context of the deportation and extermination of the European Jews and by drawing on contemporary sources which hint to such a – now lost – !lm project, the essay examines the available evidence and investigates comparable footage, arguing that the gaze of the perpetrators has long been part of our collective visual memory of the Holocaust. Keywords Holocaust, visual propaganda, documentary !lm, !lm archives, concentration camps, ghettos, Reichs!lmarchiv, Budd Schulberg Full Text: HTMLHTMLHTML DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17892/app.2021.00012.223http://dx.doi.org/10.17892/app.2021.00012.223http://dx.doi.org/10.17892/app.2021.00012.223 HTML http://dx.doi.org/10.17892/app.2021.00012.223 Apparatus. ISSN 2365-7758 Atrocity Film author: Fabian Schmidt and Alexander Oliver Zöller date: 2021 issue: 12 toc: yes abstract: What if the SS as the main Nazi organisation responsible for the Holocaust produced a secret film about the persecution and murder of the European Jews during World War 2? The essay discusses the possible production of a documentary film about the genocide, made by the perpetrators. -

An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps

Chaos, Coercion, and Organized Resistance; An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas Vernon Maher Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. J. Craig Jenkins, Co-Advisor Dr. Vincent Roscigno, Co-Advisor Dr. Andrew W. Martin Copyright by Thomas V. Maher 2013 Abstract Research on organizations and bureaucracy has focused extensively on issues of efficiency and economic production, but has had surprisingly little to say about power and chaos (see Perrow 1985; Clegg, Courpasson, and Phillips 2006), particularly in regard to decoupling, bureaucracy, or organized resistance. This dissertation adds to our understanding of power and resistance in coercive organizations by conducting an analysis of the Nazi concentration camp system and nineteen concentration camps within it. The concentration camps were highly repressive organizations, but, the fact that they behaved in familiar bureaucratic ways (Bauman 1989; Hilberg 2001) raises several questions; what were the bureaucratic rules and regulations of the camps, and why did they descend into chaos? How did power and coercion vary across camps? Finally, how did varying organizational, cultural and demographic factors link together to enable or deter resistance in the camps? In order address these questions, I draw on data collected from several sources including the Nuremberg trials, published and unpublished prisoner diaries, memoirs, and testimonies, as well as secondary material on the structure of the camp system, individual camp histories, and the resistance organizations within them. My primary sources of data are 249 Holocaust testimonies collected from three archives and content coded based on eight broad categories [arrival, labor, structure, guards, rules, abuse, culture, and resistance]. -

Musique Et Camps De Concentration

Colloque « MusiqueColloque et « campsMusique de concentration »et camps de Conseilconcentration de l’Europe - 7 et 8 novembre » 2013 dans le cadre du programme « Transmission de la mémoire de l’Holocauste et prévention des crimes contre l’humanité » Conseil de l’Europe - 7 et 8 novembre 2013 Éditions du Forum Voix Etouffées en partenariat avec le Conseil de l’Europe 1 Musique et camps de concentration Éditeur : Amaury du Closel Co-éditeur : Conseil de l’Europe Contributeurs : Amaury du Closel Francesco Lotoro Dr. Milijana Pavlovic Dr. Katarzyna Naliwajek-Mazurek Ronald Leopoldi Dr. Suzanne Snizek Dr. Inna Klause Daniel Elphick Dr. David Fligg Dr. h.c. Philippe Olivier Lloica Czackis Dr. Edward Hafer Jory Debenham Dr. Katia Chornik Les vues exprimées dans cet ouvrage sont de la responsabilité des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement la ligne officielle du Conseil de l’Europe. 2 Sommaire Amaury du Closel : Introduction 4 Francesco Lotoro : Searching for Lost Music 6 Dr Milijana Pavlovic : Alma Rosé and the Lagerkapelle Auschwitz 22 Dr Katarzyna Naliwajek–Mazurek : Music within the Nazi Genocide System in Occupied Poland: Facts and Testimonies 38 Ronald Leopoldi : Hermann Leopoldi et l’Hymne de Buchenwald 49 Dr Suzanne Snizek : Interned musicians 53 Dr Inna Klause : Musicocultural Behaviour of Gulag prisoners from the 1920s to 1950s 74 Daniel Elphick : Mieczyslaw Weinberg: Lines that have escaped destruction 97 Dr David Fligg : Positioning Gideon Klein 114 Dr. h.c. Philippe Olivier : La vie musicale dans le Ghetto de Vilne : un essai -

Hannah's Suitcase Quiz

question answer page Who is the author of Hannah's Suitcase? Karen Levine cover Who wrote 'The Diary of a Young Girl'? Anne Franke foreward Who was the teacher at the Tokyo Holocaust Center who searched for Hannah's story? Fumiko Ishioka foreward Where was Hannah's suitcase Auschwitz death camp in southern confiscated? Poland foreward Be vigilant to inhumanity, prejudice, bigotry, and the terrible What does Hana's story remind us to consequences of silence, do? indifference, and apathy. foreward Who wrote the forward to Hana's Suitcase? Archibishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu foreward In which country did Hana and her family live in the 30's and 40's? Czechoslovakia Intro Between what years did World War II take place? Between 1939 anbd 1945 Intro Who was the dictator in Germany in the 1940's? Adolf Hitler Intro Who did Adolf Hitler want to eliminate from the face of the earth? The Jewish people Intro What were the prison camps also called? concentration camps Intro How many Jewish people were killed during World War II? 6 million Intro How many of the 6 million Jewish people killed during World War II were children? One and a half million Intro In what year did World War II end? 1945 Intro What is the worst example of mass murder called? holocaust Intro Which country allied with Nazi Germany during the second World War? Japan Intro In what year was the Children's Forum on the Holocaust held in Tokyo? 1999 Intro What was the name of the Holocaust survivor Japanese children met in 1999 at the Children's Forum on the Holocaust in Tokyo? Yaffa -

Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications

Manuscript version: Author’s Accepted Manuscript The version presented in WRAP is the author’s accepted manuscript and may differ from the published version or Version of Record. Persistent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/103717 How to cite: Please refer to published version for the most recent bibliographic citation information. If a published version is known of, the repository item page linked to above, will contain details on accessing it. Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: Please refer to the repository item page, publisher’s statement section, for further information. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected]. warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Medicine in Theresienstadt Abstract: Illness was a defining experience for prisoners of Nazi concentration camps and ghettos, and yet their medical history is missing; a startling lacuna, given the extensive research into medicine and the Holocaust. -

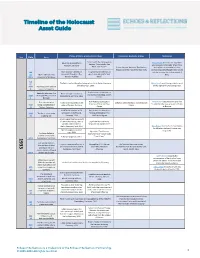

Timeline of the Holocaust Asset Guide

Timeline of the Holocaust Asset Guide Photos, Artifacts, & Instructional Videos Documents, Handouts, & Maps Testimonies Year Date Entry Stickers with Nazi propaganda Hindenburg and Hitler in Harry Hankin describes the day Hitler slogans: "One People, One Potsdam, Germany was appointed Chancellor of Germany Reich, One Fuhrer" Echoes Student Handout: The Weimar and reflects on the belief of older Republic and the Rise of the Nazi Party German Jews who thought Hitler would JAN Key Historical Concepts in A sign calling on Germans to only be in power for a short period of 30- Adolf Hitler becomes Holocaust Education: The greet each other with "Heil time. FEB 1 chancellor of Germany Weimar Republic Hitler" FEB The Reichstag building after being set on fire in Berlin, Germany, Henry Small recalls being called to work 27- on February 27, 1933 on the night of the Reichstag arson. MAR Reichstag arson leads to 5 state of emergency Graph: results of elections to Reichstag elections: the Hitler voting in elections at the German Reichstag, March MAR Nazis gain 44 percent of Koenigsberg, Germany, 1933 5, 1933 5 the vote Key Historical Concepts in Herbert Kahn describes why and how First concentration A view of the barracks in the Echoes Student Handout: Concentration Holocaust Education: Nazi his older brother was arrested and sent MAR camp is established in camp of Dachau, Germany Camps 22 Dachau, Germany Camps to Dachau. Adolf Hitler watches an SA Key Historical Concepts in MAR The Nazis sponsor the procession in Dortmund, Holocaust Education: The 24 Enabling Act Germany, 1933 Totalitarian Regime A man supporting the boycott of Jewish businesses, next to Sign from Nazi Germany: a Jewish-owned store in "Jews are not wanted here" Berlin, Germany, April 1933 Otto Hertz remembers the humiliation he felt when his family's store was Nazi propaganda, boycott boycotted. -

Terezin Resources

Terezin Resources Websites Theresienstadt. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?ModuleId=10005424 The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum describes the three main functions of the ghetto and explains how the Nazis were able to deceive the rest of the world regarding their treatment of the Jews. Terezin (Theresienstadt) Concentration Camp. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/terezin.html The Jewish Virtual Library tells the story of Terezin from its creation in 1780 to serve as a fortress protecting Prague from invaders to the “city built for the Jews.” Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. http://www1.yadvashem.org/education/terezin/eng/lexicon.htm Yad Vashem offers a glossary of terms associated with the Terezin ghetto, a timeline associated to Hitler’s takeover of Terezin, a picture gallery collected from the Terezin ghetto, a lesson plan for teachers, and additional materials of interest to educators. Virtual Tour of Theresienstadt. http://history1900s.about.com/library/holocaust/aa012599.htm This virtual tour of Theresienstadt shows the ghetto room by room and explains the purpose for each room. Books Berkley, George E. Hitler's Gift: The Story of Theresienstadt. Boston: Branden Books, 1993. Bondy, Ruth. "Elder of the Jews": Jakob Edelstein of Theresienstadt. New York: Grove Press, 1989. Bor, Josef. The Terezin Requiem. New York: Knopf, 1963. Brenner, Hannelore. The Girls of Room 28: Friendship, Hope, and Survival in Theresienstadt. Schocken. 2009. Friedman, Saul S., ed. The Terezin Diary of Gonda Redlich. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992. Friesova, Jana Renee. Fortress of My Youth: Memoir of a Terezín Survivor.