RESISTANCE During the Holocaust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jews and African Americans: Slavery, Diaspora, Ghetto

University of California at San Diego Jews and African Americans: Slavery, Diaspora, Ghetto HITO 136 Fall 2018 Professor Deborah Hertz HSS 6024 Please refrain from emailing me unless it is an emergency. Better to catch me after class. In an absolute emergency contact me at [email protected]. Class meets Tuesdays and Thursdays from 12:30 to 1:50 in Pepper Canyon Hall 121 Office hours: Tuesdays 10-11:30 in HSS 6024 and by appointment. Class web site can be found on Triton Ed. Power Point slides will be posted up shortly before the class meets on Tuesday and Thursday mornings. You will be writing short blogs on the Discussion Forum. Check your UCSD email regularly as I often send reminder emails to the entire class. Manners in the Classroom. Please come to class on time and do not leave class before the class is over. If you must leave early, kindly let the instructor know before class begins and sit near the back. Although our class meets over the lunch hour, please do not eat during class, although it is fine to drink liquids. Attendance will not be taken but the sight of empty seats is extremely distressing to the instructor. No clickers!!! 1 Readings can be found in various places, in paper and digital form. All of the assigned texts have been ordered at the Price Center Bookstore and are also on reserve at the Library. The Reader for the class can be purchased in the bookstore and several copies of the Reader are also on reserve. -

From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizensâ•Ž Motives Near

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Tenth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2019 From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the European History Commons, and the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons Green, Jordan, "From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust" (2019). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2019/holocaust/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green History 395 James Madison University Spring 2018 Dr. Michael J. Galgano The Holocaust has raised difficult questions since its end in April 1945 including how could such an atrocity happen and how could ordinary people carry out a policy of extermination against a whole race? To answer these puzzling questions, most historians look inside the Nazi Party to discern the Holocaust’s inner-workings: official decrees and memos against the Jews and other untermenschen1, the role of the SS, and the organization and brutality within concentration and extermination camps. However, a vital question about the Holocaust is missing when examining these criteria: who was watching? Through research, the local inhabitants’ knowledge of a nearby concentration camp, extermination camp or mass shooting site and its purpose was evident and widespread. -

Michalina Tatarkówna-Majkowska Biografia

Uniwersytet Łódzki Wydział Filozoficzno – Historyczny Piotr Ossowski Michalina Tatarkówna-Majkowska Biografia Praca doktorska napisana w Katedrze Historii Polski i Świata po 1945 r. pod kierunkiem prof. nadzw. dr hab. Krzysztofa Lesiakowskiego Łódź 2016 2 SPIS TRE ŚCI Wykaz skrótów……………………………………………………………………......... 5 Wst ęp…………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Rozdział I Robotnicza dola (1908-1945)……………………………………… 22 Rozdział II Pocz ątek kariery politycznej (1945-1953)………………………… 55 1. W Komitecie Dzielnicowym PPR Łód ź Widzew…………. 55 2. W czasach stalinowskich…………………………………... 77 Rozdział III W kr ęgu elity władzy (1953-1955)………………………………... 84 1. Obj ęcie stanowiska I sekretarza KW PZPR w Łodzi……… 84 2. Kierownik polityczny województwa łódzkiego…………… 89 Rozdział IV Burzliwe lata (1955-1957)………………………………………… 109 1. Okoliczno ści awansu na I sekretarza KŁ PZPR…………… 109 2. W obliczu walk frakcyjnych w PZPR……………………... 113 3. Przełom pa ździernikowy po łódzku………………………... 133 4. Sprawdzian wyborczy w styczniu 1957 r………………….. 140 Rozdział V Zwierzchnik łódzkiej organizacji partyjnej (1955-1964)………….. 156 1. Działalno ść na forum Egzekutywy KŁ PZPR……………... 156 2. System nomenklatury i polityka kadrowa………………….. 159 3. Wpływ na funkcjonowanie lokalnego aparatu partyjnego…. 168 4. Udział w ogólnopolskim życiu politycznym………………. 175 5. Posłanka na Sejm…………………………………………... 184 6. Funkcja reprezentacyjna: podró że zagraniczne i przyjmowanie go ści………………………………………. 188 7. Wyró żnienia i odznaczenia………………………………… 192 Rozdział VI Ró żne barwy rz ądzenia Łodzi ą (1955-1964)……………………… 195 1. Wobec problemów mieszka ńców………………………….. 195 2. Laicyzacja i ideologizacja o światy………………………… 200 3. Udział w przebudowie miasta……………………………… 216 4. Kształtowanie życia kulturalnego………………………….. 228 5. Świ ęta i rocznice…………………………………………… 243 3 Rozdział VII Na emeryturze (1964-1986)……………………………………….. 248 1. Odwołanie ze stanowiska I sekretarza KŁ PZPR…………. -

White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with Myspace and Facebook.” in Race After the Internet (Eds

CITATION: boyd, danah. (2011). “White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook.” In Race After the Internet (eds. Lisa Nakamura and Peter A. Chow-White). Routledge, pp. 203-222. White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook danah boyd Microsoft Research and HarVard Berkman Center for Internet and Society http://www.danah.org/ In a historic small town outside Boston, I interViewed a group of teens at a small charter school that included middle-class students seeking an alternative to the public school and poorer students who were struggling in traditional schools. There, I met Kat, a white 14-year-old from a comfortable background. We were talking about the social media practices of her classmates when I asked her why most of her friends were moVing from MySpace to Facebook. Kat grew noticeably uncomfortable. She began simply, noting that “MySpace is just old now and it’s boring.” But then she paused, looked down at the table, and continued. “It’s not really racist, but I guess you could say that. I’m not really into racism, but I think that MySpace now is more like ghetto or whatever.” – Kat On that spring day in 2007, Kat helped me finally understand a pattern that I had been noticing throughout that school year. Teen preference for MySpace or 1 Feedback welcome! [email protected] CITATION: boyd, danah. (2011). “White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook.” In Race After the Internet (eds. -

Resistance Rising: Fighting the Shadow War Against the Germans

Activity: Resistance Rising: Fighting the Shadow War against the Germans Guiding question: What, if any, impact did the French Resistance have on the Allied invasion of France? DEVELOPED BY MATTHEW POTH Grade Level(s): 6-8, 9-12 Subject(s): Social Studies, English/Language Arts, Journalism Cemetery Connection: Rhone American Cemetery Fallen Hero Connection: Sergeant Charles R. Perry Activity: Resistance Rising: Fighting the Shadow War against the Germans 1 Overview Using primary and secondary sources and interactive maps from the American Battle Monuments Commission, stu- dents will learn about the impact of the French Resistance “Often, civilians and on the battle for France and the overall outcome of the war. members of the military in Students will critically analyze documents to learn about the non-traditional roles are overlooked when teaching ways in which the Resistance operated. Students will create World War II. To more fully a newspaper to inform the public and recruit potential mem- understand the impact and bers to the movement. scale of the war, students must hear the stories of these men and women.” Historical Context — Matthew Poth The French Resistance was a collection of French citizens who united against the German occupation. In addition to the Poth is a teacher at Park View High School German military, which controlled northern France, many in Sterling, Virginia. French people objected to the Vichy government, the govern- ment of southern France led by World War I General Marshal Philippe Pétain. The Resistance played a vital role in the Allied advancement through France. With the aid of the men and women of the Resistance, the Allies gathered accurate intelligence on the Atlantic Wall, the deployment of German troops, and the capabilities of their enemy. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

Abba Kovner - Yitzchak Zuckerman - Two Approaches to the Jewish Exodus from Europe Shalom Cholawski

Abba Kovner - Yitzchak Zuckerman - Two Approaches to the Jewish Exodus from Europe Shalom Cholawski In December 1944, partisans from Vilna and Kovno met in Lublin. Those who arrived from the Soviet Union immediately began organizing the Bericha in motion. On January 20, 1945, a few days after the liberation of Warsaw, Yitzchak Zuckerman and Zivia Lubetkin, two of the commanders of the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt, arrived in Lublin and met with Kovner and his colleagues from the partisans. Kovner later recalled his meeting with Zuckerman: “His face, like mine, was drawn, haggard in the flame of a small candle, and the candle, standing on the low stool between us, flickered as though at the foot of a dead man. Only our shadows on the naked walls were long and mute.” Zuckerman and Kovner concurred that no Jewish community could be established in the graveyard that was now Poland. The only course was to press for Aliyah through every possible means. However, they disagreed as to the modus operandi. Yitzchak Zuckerman argued that the group of pioneer leaders must not abandon the remnant of Polish Jewry. It was the duty of the leadership to organize and bring them to Eretz Israel. The veteran leadership was no longer in existence, and it devolved on the younger people who had survived, the ghetto fighters and partisans, to create the organizational framework needed to remove the Jews from Poland. Zuckerman said the departure of the activists would be tantamount to desertion and therefore intolerable. Kovner said they must leave the detested soil of Europe at once, and in the course of leaving take their revenge on Nazis who were still walking about __________________________________________________________________________ מרכז המידע אודות השואה, יד ושם ביה"ס המרכזי להוראת השואה 1 freely. -

Biuletynbiuletyn Instytutuinstytutu Pamięcipamięci Narodowejnarodowej

NR 3–4 (62–63) marzec–kwiecień 2006 BIULETYNBIULETYN INSTYTUTUINSTYTUTU PAMIĘCIPAMIĘCI NARODOWEJNARODOWEJ Spod czerwonej ISSN 1641-9561 gwiazdy 9 771641 956001 numer indeksu 374431 nakład 3500 egz. cena 7,50 zł (w(w tymtym 0%0% VAT)VAT) ADRESY I TELEFONY ODDZIAŁÓW IPN W POLSCE BIAŁYSTOK ul. Warsztatowa 1a, 15-637 Białystok tel. (0-85) 664 57 03 GDYNIA ul. Witomińska 19, 81-311 Gdynia tel. (0-58) 660 67 00 fax (0-58) 660 67 01 KATOWICE ul. Kilińskiego 9, 40-061 Katowice tel. (0-32) 609 98 40 KRAKÓW ul. Reformacka 3, 31-012 Kraków tel. (0-12) 421 11 00 LUBLIN ul. Wieniawska 15, 20-071 Lublin tel. (0-81) 534 59 11 ŁÓDŹ ul. Orzeszkowej 31/35, 91-479 Łódź tel. (0-42) 616 27 45 POZNAŃ ul. Rolna 45a, 61-487 Poznań tel. (0-61) 835 69 00 RZESZÓW ul. Słowackiego 18, 35-060 Rzeszów tel. (0-17) 860 60 18 SZCZECIN ul. K. Janickiego 30, 71-270 Szczecin tel. (0-91) 484 98 00 WARSZAWA pl. Krasińskich 2/4/6, 00-207 Warszawa tel. (0-22) 530 86 25 WROCŁAW ul. Sołtysowicka 23, 51-168 Wrocław tel. (0-71) 326 76 00 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU PAMIĘCI NARODOWEJ Redaguje Biuro Edukacji Publicznej IPN Zespół redakcyjny: Władysław Bułhak (redaktor naczelny), Janusz Kotański, Krzysztof Madej, Bartłomiej Noszczak, Barbara Polak, Jan M. Ruman, Jan Żaryn Projekt graficzny: Krzysztof Findziński Redakcja techniczna: Andrzej Broniak Skład i łamanie: Wojciech Czaplicki Korekta: Anna Kaniewska Adres: ul. Towarowa 28, 00-839 Warszawa Tel. (0-22) 581 89 24, fax (0-22) 581 89 26 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.ipn.gov.pl Druk: Instytut Technologii Eksploatacji ul. -

Yudkin on Porat, 'The Fall of a Sparrow: the Life and Times of Abba Kovner'

H-Judaic Yudkin on Porat, 'The Fall of a Sparrow: The Life and Times of Abba Kovner' Review published on Monday, May 3, 2010 Dina Porat. The Fall of a Sparrow: The Life and Times of Abba Kovner. Translated and edited by Elizabeth Yuval. Stanford Studies in Jewish History and Culture Series. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010. xxiv + 411 pp. $65.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8047-6248-9. Reviewed by Leon Yudkin (University College London)Published on H-Judaic (May, 2010) Commissioned by Jason Kalman A Leader Poet for the Nation We have here the first full account of the noted partisan and Hebrew poet Abba Kovner (1918-87) in an English version, translated from Hebrew by Elizabeth Yuval. Born in Sevastopol and raised in Vilna, Kovner became a leader of the partisan movement in the resistance to the Nazi invasion and conquest. The author, Dina Porat, who had only met her subject once briefly, shows some signs of hero worship. Her background account borders on hagiography, though sometimes she casts doubt on positions that Kovner adopted. Already in the preface, she praises him for the magnificence of his locks, for his beautiful Hebrew, for his sense of humor, and for the admiration that he managed to draw from all who came into contact with him. Porat opens with a description of Kovner's primary vision, namely, to provide a home for his homeless people following the devastation wrought by the Holocaust. That vision, for her, was matched by his natural gifts, leadership qualities, and intelligence. For the sake of convenience, she divides his life into four parts. -

The White Rose Program

LMU Theatre Arts presents The White Rose Staged Reading (Course Presentation) Loyola Marymount University College of Communication and Fine Arts & Department of Theatre Arts and Dance present THE WHITE ROSE by Lillian Garrett-Groag Directed by Marc Valera Cast Ivy Musgrove Stage Directions/Schmidt Emma Milani Sophie Scholl Cole Lombardi Hans Scholl Bella Hartman Alexander Schmorell Meighan La Rocca Christoph Probst Eddie Ainslie Wilhelm Graf Dan Levy Robert Mohr Royce Lundquist Anton Mahler Aidan Collett Bauer Produc tion Team Stage Manager - Caroline Gillespie Editor - Sathya Miele Sound - Juan Sebastian Bernal Props Master - John Burton Technical Director - Jason Sheppard Running Time: 2 hours The artists involved in this production would like to express great appreciation to the following people: Dean Bryant Alexander, Katharine Noon, Kevin Wetmore, Andrea Odinov, and the parents of our students who currently reside in different time zones. Acknowledging the novel challenges of the Covid era, we would like to recognize the extraordinary efforts of our production team: Jason Sheppard, Sathya Miele, Juan Sebastian Bernal, John Burton, and Caroline Gillespie. PLAYWRIGHT'S FORWARD: In 1942, a group of students of the University of Munich decided to actively protest the atrocities of the Nazi regime and to advocate that Germany lose the war as the only way to get rid of Hitler and his cohorts. They asked for resistance and sabotage of the war effort, among other things. They published their thoughts in five separate anonymous leaflets which they titled, 'The White Rose,' and which were distributed throughout Germany and Austria during the Summer of 1942 and Winter of 1943. -

Nazi Concentration Camp Guard Service Equals "Good Moral Character"?: United States V

American University International Law Review Volume 12 | Issue 1 Article 3 1997 Nazi Concentration Camp Guard Service Equals "Good Moral Character"?: United States v. Lindert K. Lesli Ligomer Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Ligorner, K. Lesli. "Nazi Concentration Camp Guard Service Equals "Good Moral Character"?: United States v. Lindert." American University International Law Review 12, no. 1 (1997): 145-193. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMP GUARD SERVICE EQUALS "GOODMORAL CHARACTER"?: UNITED STATES V. LINDERT By K Lesli Ligorner Fetching the newspaper from your porch, you look up and wave at your elderly neighbor across the street. This quiet man emigrated to the United States from Europe in the 1950s. Upon scanning the newspaper, you discover his picture on the front page and a story revealing that he guarded a notorious Nazi concen- tration camp. How would you react if you knew that this neighbor became a natu- ralized citizen in 1962 and that naturalization requires "good moral character"? The systematic persecution and destruction of innocent peoples from 1933 until 1945 remains a dark chapter in the annals of twentieth century history. Though the War Crimes Trials at Nilnberg' occurred over fifty years ago, the search for those who participated in Nazi-sponsored persecution has not ended. -

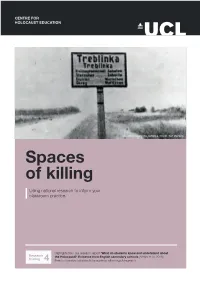

Spaces of Killing Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION The entrance sign to Treblinka. Credit: Yad Vashem Spaces of killing Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016) briefing 4 Free to download at www.holocausteducation.org.uk/research If students are to understand the significance of the Holocaust and the full enormity of its scope and scale, they need to appreciate that it was a continent-wide genocide. Why does this matter? The perpetrators ultimately sought to kill every Jew, everywhere they could reach them with victims Knowledge of the ‘spaces of killing’ is crucial to an understanding of the uprooted from communities across Europe. It is therefore crucial to know about the geography of the Holocaust. If students do not appreciate the scale of the killings outside of Holocaust relating to the development of the concentration camp system; the location, role and purpose Germany and particularly the East, then it is impossible to grasp the devastation of the ghettos; where and when Nazi killing squads committed mass shootings; and the evolution of the of Jewish communities in Europe or the destruction of diverse and vibrant death camps. cultures that had developed over centuries. This briefing, the fourth in our series, explores students’ knowledge and understanding of these key Entire communities lost issues, drawing on survey research and focus group interviews with more than 8,000 11 to 18 year olds. Thousands of small towns and villages in Poland, Ukraine, Crimea, the Baltic states and Russia, which had a majority Jewish population before the war, are now home to not a single Jewish person.