Downloads/.Last Accessed: 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

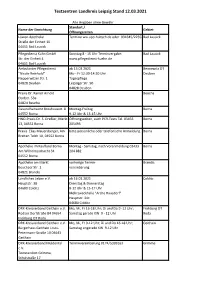

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 12.03.2021

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 12.03.2021 Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr Standort / Name der Einrichtung Gebiet Öffnungszeiten Löwen Apotheke Termine ww.apo-hultsch.de oder 034345/22352Bad Lausick Straße der Einheit 10 04651 Bad Lausick Pflegedienst Kühn GmbH Sonntag 8 - 15 Uhr Terminvergabe: Bad Lausick Str. der Einheit 4 www.pflegedienst-kuehn.de 04651 Bad Lausick Ambulanter Pflegedienst ab 15.03.2021 Bennewitz OT "Nicole Reinhold" Mo - Fr 12:30-14:30 Uhr Deuben Nepperwitzer Str. 1 Tagespflege 04828 Deuben Leipziger Str. 90 04828 Deuben Praxis Dr. Rainer Arnold Beucha Dorfstr. 53a 04824 Beucha Gesundheitsamt Brauhausstr. 8 Montag-Freitag Borna 04552 Borna 9-12 Uhr & 13-15 Uhr HNO-Praxis Dr. S. Dreßler, Markt Öffnungszeiten, auch PCR-Tests Tel. 03433 Borna 13, 04552 Borna 205495 Praxis Elias Mauersberger, Am bitte persönliche oder telefonische Anmeldung. Borna Breiten Teich 10, 04552 Borna Apotheke im Kaufland Borna Montag - Samstag, nach Voranmeldung 03433 Borna Am Wilhelmsschacht 34 204 882 04552 Borna Apotheke am Markt vorherige Termin- Brandis Beuchaer Str. 1 vereinbarung 04821 Brandis Ländliches Leben e.V. ab 16.03.2021 Colditz Hauptstr. 38 Dienstag & Donnerstag 04680 Colditz 8-12 Uhr & 15-17 Uhr Mehrzweckhalle "Arche Hausdorf" Hauptstr. 34c 04680 Colditz DRK-Kreisverband Geithain e.V. Mo, Mi, Fr 16-18 Uhr; Di und Do 9 -12 Uhr; Frohburg OT Rodaer Dorfstraße 84 04654 Samstag gerade KW 9 - 12 Uhr Roda Frohburg OT Roda DRK-Kreisverband Geithain e.V. Mo, Mi, Fr 9-12 Uhr; Di und Do 16-18 Uhr; Geithain Bürgerhaus Geithain Louis- Samstag ungerade KW 9-12 Uhr Petermann-Straße 10 04643 Geithain DRK-Kreisverband Muldental Terminvereinbarung 0174/5399163 Grimma e.V. -

A Matter of Comparison: the Holocaust, Genocides and Crimes Against Humanity an Analysis and Overview of Comparative Literature and Programs

O C A U H O L S T L E A C N O N I T A A I N R L E T L N I A R E E M C E M B R A N A Matter Of Comparison: The Holocaust, Genocides and Crimes Against Humanity An Analysis And Overview Of Comparative Literature and Programs Koen Kluessien & Carse Ramos December 2018 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance A Matter of Comparison About the IHRA The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) is an intergovernmental body whose purpose is to place political and social leaders’ support behind the need for Holocaust education, remembrance and research both nationally and internationally. The IHRA (formerly the Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research, or ITF) was initiated in 1998 by former Swedish Prime Minister Göran Persson. Persson decided to establish an international organisation that would expand Holocaust education worldwide, and asked former president Bill Clinton and former British prime minister Tony Blair to join him in this effort. Persson also developed the idea of an international forum of governments interested in discussing Holocaust education, which took place in Stockholm between 27–29 January 2000. The Forum was attended by the representatives of 46 governments including; 23 Heads of State or Prime Ministers and 14 Deputy Prime Ministers or Ministers. The Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust was the outcome of the Forum’s deliberations and is the foundation of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. The IHRA currently has 31 Member Countries, 10 Observer Countries and seven Permanent International Partners. -

Telefonverzeichnis Der Kreisverwaltung Des Landkreises Waldeck-Frankenberg in Korbach (März 2021)

Telefonverzeichnis der Kreisverwaltung des Landkreises Waldeck-Frankenberg in Korbach (März 2021) Kreishaus Bürogebäude Bürogebäude Bürogebäude Bürogebäude Südring 2 Am Kniep 50 Briloner Landstraße 60 Auf Lülingskreuz 60 Auf dem Hagendorf 1 Zentrale 05631 954-0 Zentrale 05631 954-0 Zentrale 05631 954-0 Zentrale 05631 954-800 Zentrale 05631 954-0 Merhof, Oliver (FD 1.1) 232 Freund, Helene 298 Knoche, Wilhelm 809 Herguth, Harald 252 Landrat und Vorzimmer Staude, Ronja 327 Iwaniak, Martina 244 Kuklovsky, Katharina 562 Heß, Maximilian 257 Emde, Hannelore 202 Ußpelkat, Ralf 180 Korschewsky, Monika 242 Müller, Tanja 120 Höhle, Rüdiger 251 Kubat, Dr. Reinhard 202 Kramer, Dirk 279 Müller, Ursula 889 Knippschild, Gina Tabea 559 1.2 Fachdienst Personal Michel, Andrea 334 Rieb, Susanne 561 Kreitsch, Martin 245 Erster Kreisbeigeordneter und Blumenstein, Julia 538 Vorzimmer Röse, Regina 537 Rinklin, Walter 811 Meyer, Marina 515 Fisseler, Bernd 302 Frese, Karl-Friedrich 335 Ruckert, Sarah 312 Römer, Dr. Jürgen 449 Przybilla, Nancy 558 Hellwig, Petra 307 Kuhn, Heike 336 Rummel, Madeline 299 Schneider, Theresia 853 Rampelt, Jan-Hendrik 250 Henkler, Cornelia 301 Sauerwald, Annette 283 Schultz, Ute 534 Tripp, Sigrid 249 Kreisbeigeordneter Hesse-Kaufhold, Annegret 303 Schürmann, Sophia 315 Weber, Irmhild 818 Weidenhagen, Thorsten 248 Schäfer, Friedrich 392 Jauernig, Tatjana 229 Schwarz, Timo 308 Wenzel, Antje 808 Witte, Holger 246 Kiepe, Karl-Heinz 304 Spratte, Monika 126 Kreisbeigeordnete Lichanow, Viktoria 398 Stark, Almut 383 2.3 Fachdienst Öffentlichkeitsarbeit, 2.6 Fachdienst Informationstechnik Kultur, Paten- und Partnerschaften und digitale Verwaltung Behle, Hannelore 323 Mann, Andreas (FD 1.2) 388 Stracke, Reiner 314 Frömel, Petra 337 Arnold, Christian 435 Merhof, Heidrun 309 Wagner, Uwe 241 Büroleitung Heimbuchner, Ann-Katrin 338 Baraniak, Wolfgang 330 Möller, Annika 305 Webelhuth, Anne 244 Mann, Andreas (BL) 388 Reitmaier, Tanja (FD 2.3) 517 Berkenkopf, Markus 405 Querl, Marie-Luise 365 Wilke, Harald 311 Wecker, Dr. -

Holocaust Archaeology: Archaeological Approaches to Landscapes of Nazi Genocide and Persecution

HOLOCAUST ARCHAEOLOGY: ARCHAEOLOGICAL APPROACHES TO LANDSCAPES OF NAZI GENOCIDE AND PERSECUTION BY CAROLINE STURDY COLLS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The landscapes and material remains of the Holocaust survive in various forms as physical reminders of the suffering and persecution of this period in European history. However, whilst clearly defined historical narratives exist, many of the archaeological remnants of these sites remain ill-defined, unrecorded and even, in some cases, unlocated. Such a situation has arisen as a result of a number of political, social, ethical and religious factors which, coupled with the scale of the crimes, has often inhibited systematic search. This thesis will outline how a non- invasive archaeological methodology has been implemented at two case study sites, with such issues at its core, thus allowing them to be addressed in terms of their scientific and historical value, whilst acknowledging their commemorative and religious significance. -

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 07.05.2021

Testzentren Landkreis Leipzig Stand 07.05.2021 Zu den genannten Einrichtungen bieten auch Ärzte die Tests an Name der Einrichtung Standort / Gebiet Versorgungsform Öffnungszeiten TmH Transport mit Telefonische Terminvereinbarung mobil Sonstiges Herz,Hauptstr. 66 unter 034345 55751 Kerstin 04668 Otterwisch Engelmann DRK Kreisverband Terminvergabe: mobil Sonstiges Muldental e.V. www.drkmuldental.de/schnelltest Standorte Walther-Rathenau-Str. oder 0174 5499100 oder 0174 Nerchau, 1, 04808 Wurzen 5399163 Dürrweitzschen, Mutzschen, Großbardau, Großbothen lola-Aquarium Netto-Markt 9-17 Uhr mobil Sonstiges Ostenstr. 9 Montag: Carsdorfer Str. 8 Pegau Netto-Märkte in 08527 Plauen Dienstag: Schusterstr. 6 Groitzsch Pegau, Mittwoch / Freitag: Groitzsch und Pawlowstr. 2a Borna Borna Donnerstag: Deutzener Str. 7 Borna Löwen Apotheke Termine ww.apo-hultsch.de oder Bad Lausick Apotheke Straße der Einheit 10 034345/22352 04651 Bad Lausick Pflegedienst Kühn Mo - Fr von 13 - 14:30 Uhr, So von Bad Lausick amb. PD GmbH, Str. der Einheit 8 - 15 Uhr Terminvergabe: 4, 04651 Bad Lausick www.pflegedienst-kuehn.de DRK-Kreisverband Kur- und Freizeitbad Riff Bad Lausick Geithain e.V. Am Riff 3, 04651 Bad Lausick Kreisgeschäftsstelle Dresdener Str. 33 b Mo / Mi / Do 9 – 11 Uhr 04643 Geithain Di / Fr 16 – 18 Uhr Häusliche Kranken- Mittwoch 9 - 15 Uhr Bad Lausick Sonstiges und Altenpflege Dorothea Petzold GmbH, Fabianstr. 6 04651 Bad Lausick DRK-Kreisverband Kur- und Freizeitbad Riff Bad Lausick Hilforga- Geithain e.V. Am Riff 3, 04651 Bad Lausick nisation Kreisgeschäftsstelle Mo / Mi / Do 9 – 11 Uhr Dresdener Str. 33 b Di / Fr 16 – 18 Uhr 04643 Geithain DRK WPS im DRK Pflegedienst Bennewitz Bennewitz Sonstiges Muldental GmbH, Leipziger Str. -

What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster, Alice Pettigrew, Andy Pearce, Rebecca Hale Centre for Holocaust Education Centre Adrian Burgess, Paul Salmons, Ruth-Anne Lenga Centre for Holocaust Education What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Cover image: Photo by Olivia Hemingway, 2014 What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster Alice Pettigrew Andy Pearce Rebecca Hale Adrian Burgess Paul Salmons Ruth-Anne Lenga ISBN: 978-0-9933711-0-3 [email protected] British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record is available from the British Library All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permissions of the publisher. iii Contents About the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education iv Acknowledgements and authorship iv Glossary v Foreword by Sir Peter Bazalgette vi Foreword by Professor Yehuda Bauer viii Executive summary 1 Part I Introductions 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Methodology 23 Part II Conceptions and encounters 35 3. Collective conceptions of the Holocaust 37 4. Encountering representations of the Holocaust in classrooms and beyond 71 Part III Historical knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust 99 Preface 101 5. Who were the victims? 105 6. -

Holocaust/Shoah the Organization of the Jewish Refugees in Italy Holocaust Commemoration in Present-Day Poland

NOW AVAILABLE remembrance a n d s o l i d a r i t y Holocaust/Shoah The Organization of the Jewish Refugees in Italy Holocaust Commemoration in Present-day Poland in 20 th century european history Ways of Survival as Revealed in the Files EUROPEAN REMEMBRANCE of the Ghetto Courts and Police in Lithuania – LECTURES, DISCUSSIONS, remembrance COMMENTARIES, 2012–16 and solidarity in 20 th This publication features the century most significant texts from the european annual European Remembrance history Symposium (2012–16) – one of the main events organized by the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity in Gdańsk, Berlin, Prague, Vienna and Budapest. The 2017 issue symposium entitled ‘Violence in number the 20th-century European history: educating, commemorating, 5 – december documenting’ will take place in Brussels. Lectures presented there will be included in the next Studies issue. 2016 Read Remembrance and Solidarity Studies online: enrs.eu/studies number 5 www.enrs.eu ISSUE NUMBER 5 DECEMBER 2016 REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY EDITED BY Dan Michman and Matthias Weber EDITORIAL BOARD ISSUE EDITORS: Prof. Dan Michman Prof. Matthias Weber EDITORS: Dr Florin Abraham, Romania Dr Árpád Hornják, Hungary Dr Pavol Jakubčin, Slovakia Prof. Padraic Kenney, USA Dr Réka Földváryné Kiss, Hungary Dr Ondrej Krajňák, Slovakia Prof. Róbert Letz, Slovakia Prof. Jan Rydel, Poland Prof. Martin Schulze Wessel, Germany EDITORIAL COORDINATOR: Ewelina Pękała REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY PUBLISHER: European Network Remembrance and Solidarity ul. Wiejska 17/3, 00–480 Warszawa, Poland www.enrs.eu, [email protected] COPY-EDITING AND PROOFREADING: Caroline Brooke Johnson PROOFREADING: Ramon Shindler TYPESETTING: Marcin Kiedio GRAPHIC DESIGN: Katarzyna Erbel COVER DESIGN: © European Network Remembrance and Solidarity 2016 All rights reserved ISSN: 2084–3518 Circulation: 500 copies Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag. -

The Nazis and the German Population: a Faustian Deal? Eric A

The Nazis and the German Population: A Faustian Deal? Eric A. Johnson, Nazi Terror. The Gestapo, Jews, and Ordinary Germans, New York: Basic Books, 2000, 636 pp. Reviewed by David Bankier Most books, both scholarly and popular, written on relations between the Gestapo and the German population and published up to the early 1990s, focused on the leaderships of the organizations that powered the terror and determined its contours. These books portray the Nazi secret police as omnipotent and the population as an amorphous society that was liable to oppression and was unable to respond. This historical portrayal explained the lack of resistance to the regime. As the Nazi state was a police state, so to speak, the individual had no opportunity to take issue with its policies, let alone oppose them.1 Studies published in the past decade have begun to demystify the Gestapo by reexamining this picture. These studies have found that the German population had volunteered to assist the apparatus of oppression in its actions, including the persecution of Jews. According to the new approach, the Gestapo did not resemble the Soviet KGB, or the Romanian Securitate, or the East German Stasi. The Gestapo was a mechanism that reacted to events more than it initiated them. Chronically short of manpower, it did not post a secret agent to every street corner. On the contrary: since it did not have enough spies to meet its needs, it had to rely on a cooperative population for information and as a basis for its police actions. The German public did cooperate, and, for this reason, German society became self-policing.2 1 Edward Crankshaw, Gestapo: Instrument of Tyranny (London: Putnam, 1956); Jacques Delarue, Histoire de la Gestapo (Paris: Fayard, 1962); Arnold Roger Manvell, SS and Gestapo: Rule by Terror (London: Macdonald, 1970); Heinz Höhne, The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS (New York: Ballantine, 1977). -

The German Civil Code

TUE A ERICANI LAW REGISTER FOUNDED 1852. UNIERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA DEPART=ENT OF LAW VOL. {4 0 - S'I DECEMBER, 1902. No. 12. THE GERMAN CIVIL CODE. (Das Biirgerliche Gesetzbuch.) SOURCES-PREPARATION-ADOPTION. The magnitude of an attempt to codify the German civil. laws can be adequately appreciated only by remembering that for more than fifteefn centuries central Europe was the world's arena for startling political changes radically involv- ing territorial boundaries and of necessity affecting private as well as public law. With no thought of presenting new data, but that the reader may properly marshall events for an accurate compre- hension of the irregular development of the law into the modem and concrete results, it is necessary to call attention to some of the political- and social factors which have been potent and conspicuous since the eighth century. Notwithstanding the boast of Charles the Great that he was both master of Europe and the chosen pr6pagandist of Christianity and despite his efforts in urging general accept- ance of the Roman law, which the Latinized Celts of the western and southern parts of his titular domain had orig- THE GERM AN CIVIL CODE. inally been forced to receive and later had willingly retained, upon none of those three points did the facts sustain his van- ity. He was constrained to recognize that beyond the Rhine there were great tribes, anciently nomadic, but for some cen- turies become agricultural when not engaged in their normal and chief occupation, war, who were by no means under his control. His missii or special commissioners to those people were not well received and his laws were not much respected. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

Naturschutz Aktuell 169-187 Naturschutz Aktuell Zusammengestellt Von W

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Vogelkundliche Hefte Edertal Jahr/Year: 1987 Band/Volume: 13 Autor(en)/Author(s): Lübcke Wolfgang Artikel/Article: Naturschutz aktuell 169-187 Naturschutz aktuell zusammengestellt von W. Lübcke Kurz_notiert Allendorf: Erfolgreich zur Wehr setzte sich die HGON gegen die von der Gemeinde Allendorf geplante Asphaltierung eines Feldwe ges durch die Ederauen von Rennertehausen. (FZ v. 7* u. 8.1.86) 1984 waren die Feuchtwiesen durch einen Vertrag zwischen BFN und dem Wasser- und Bodenverband Rennertehausen gesichert wor den. (Vergl. Vogelk. Hefte 11 (1985) Bad Wildungen: Die Nachfolge von Falko Emde (Bad Wildungen) als Leiter des Arbeitskreises Waldeck-Frankenberg der HGON trat Harmut Mai (Wega) an. Sein Stellvertreter wurde Bernd Hannover (Lelbach). Schriftführer bleibt Karl Sperner (Wega). (WA vom 11.1.86) Bad Wildungen: Gegen die Zerstörung von Biotopen als "private Fortsetzung der Flurbereinigung" protestierte die DBV-Gruppe Bad Wildungen. Gravierendstes Beispiel ist die Dränierung der Feucht wiesen im Dörnbachtal bei Odershausen. (WLZ v. 14.1.86) Frankenau-Altenlotheim: Ohne Baugenehmigung entstand ein Reit platz in einem Feuchtwiesengelände des Lorfetales. U. a. wurde die Maßnahme durch Kreismittel bezuschußt. Im Rahmen eines Land schaftsplanes sollen Ersatzbiotope geschaffen werden. (WLZ v. 19.3.86) Volkmarsen: Verärgert zeigte sich die Stadt Volkmarsen über die NSG-Verordnung für den Stadtbruch (WLZ v. 20.3- u. 24.7.86). Ein Antrag auf Novellierung der VO wurde von der Obersten Natur- schutzbehörde abgelehnt. Rhoden: Einen Lehrgang zum Thema "Lebensraum Wald" veranstalte te der DBV-Kreisverband vom 20. bis 22. Juni 1986 in der Wald arbeiterschule des FA Diemelstadt. -

Machbarkeitsstudie Nordkreiskommunen 23062020

23.6.2020 KOMMUNEN CÖLBE MACHBARKEITSSTUDIE : „V ERTIEFTE LAHNTAL MÜNCHHAUSEN INTE RKOMMUNALE ZUSAMMENARBEIT “ WETTER Komprax Result: Carmen Möller | Machbarkeitsstudie: „Vertiefte interkommunale Zusammenarbeit“ Inhalt 1 Präambel ....................................................................................................................................... 14 2 Zusammenfassende Ergebnisse .................................................................................................... 15 3 Anlass und Auftrag ........................................................................................................................ 16 3.1 Beschlüsse der Gemeindevertretungen / Stadtverordnetenversammlung .......................... 16 3.2 Beauftragung ......................................................................................................................... 17 3.3 Projektorganisation ............................................................................................................... 17 3.4 Mitarbeiterbeteiligung .......................................................................................................... 20 3.5 Zeitplan .................................................................................................................................. 20 3.6 Fördermittel für die Studienerstellung .................................................................................. 22 4 Ausgangslage ................................................................................................................................