State Policies Concerning Holocaust Education by Dustin D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Matter of Comparison: the Holocaust, Genocides and Crimes Against Humanity an Analysis and Overview of Comparative Literature and Programs

O C A U H O L S T L E A C N O N I T A A I N R L E T L N I A R E E M C E M B R A N A Matter Of Comparison: The Holocaust, Genocides and Crimes Against Humanity An Analysis And Overview Of Comparative Literature and Programs Koen Kluessien & Carse Ramos December 2018 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance A Matter of Comparison About the IHRA The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) is an intergovernmental body whose purpose is to place political and social leaders’ support behind the need for Holocaust education, remembrance and research both nationally and internationally. The IHRA (formerly the Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research, or ITF) was initiated in 1998 by former Swedish Prime Minister Göran Persson. Persson decided to establish an international organisation that would expand Holocaust education worldwide, and asked former president Bill Clinton and former British prime minister Tony Blair to join him in this effort. Persson also developed the idea of an international forum of governments interested in discussing Holocaust education, which took place in Stockholm between 27–29 January 2000. The Forum was attended by the representatives of 46 governments including; 23 Heads of State or Prime Ministers and 14 Deputy Prime Ministers or Ministers. The Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust was the outcome of the Forum’s deliberations and is the foundation of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. The IHRA currently has 31 Member Countries, 10 Observer Countries and seven Permanent International Partners. -

What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster, Alice Pettigrew, Andy Pearce, Rebecca Hale Centre for Holocaust Education Centre Adrian Burgess, Paul Salmons, Ruth-Anne Lenga Centre for Holocaust Education What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Cover image: Photo by Olivia Hemingway, 2014 What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster Alice Pettigrew Andy Pearce Rebecca Hale Adrian Burgess Paul Salmons Ruth-Anne Lenga ISBN: 978-0-9933711-0-3 [email protected] British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record is available from the British Library All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permissions of the publisher. iii Contents About the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education iv Acknowledgements and authorship iv Glossary v Foreword by Sir Peter Bazalgette vi Foreword by Professor Yehuda Bauer viii Executive summary 1 Part I Introductions 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Methodology 23 Part II Conceptions and encounters 35 3. Collective conceptions of the Holocaust 37 4. Encountering representations of the Holocaust in classrooms and beyond 71 Part III Historical knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust 99 Preface 101 5. Who were the victims? 105 6. -

The Nazis and the German Population: a Faustian Deal? Eric A

The Nazis and the German Population: A Faustian Deal? Eric A. Johnson, Nazi Terror. The Gestapo, Jews, and Ordinary Germans, New York: Basic Books, 2000, 636 pp. Reviewed by David Bankier Most books, both scholarly and popular, written on relations between the Gestapo and the German population and published up to the early 1990s, focused on the leaderships of the organizations that powered the terror and determined its contours. These books portray the Nazi secret police as omnipotent and the population as an amorphous society that was liable to oppression and was unable to respond. This historical portrayal explained the lack of resistance to the regime. As the Nazi state was a police state, so to speak, the individual had no opportunity to take issue with its policies, let alone oppose them.1 Studies published in the past decade have begun to demystify the Gestapo by reexamining this picture. These studies have found that the German population had volunteered to assist the apparatus of oppression in its actions, including the persecution of Jews. According to the new approach, the Gestapo did not resemble the Soviet KGB, or the Romanian Securitate, or the East German Stasi. The Gestapo was a mechanism that reacted to events more than it initiated them. Chronically short of manpower, it did not post a secret agent to every street corner. On the contrary: since it did not have enough spies to meet its needs, it had to rely on a cooperative population for information and as a basis for its police actions. The German public did cooperate, and, for this reason, German society became self-policing.2 1 Edward Crankshaw, Gestapo: Instrument of Tyranny (London: Putnam, 1956); Jacques Delarue, Histoire de la Gestapo (Paris: Fayard, 1962); Arnold Roger Manvell, SS and Gestapo: Rule by Terror (London: Macdonald, 1970); Heinz Höhne, The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS (New York: Ballantine, 1977). -

The Holocaust

The Holocaust Contents The Holocaust: Theme Overview 1 Artifacts Helena Zaleska 2 Auschwitz-Birkenau, 1944 3 Star of David 4 Metal cup 5 Child’s shoe 6 The Holocaust: Theme Overview When Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power in 1933, they began to systematically remove Jews from the cultural and commercial life of Germany. Jewish property and businesses were confiscated and Jewish children were denied the right to a public education. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 further isolated Jews by revoking their citizenship. The goal was to make Germany judenrein (free of Jews). On Kristallnacht —the Night of Broken Glass — November 9, 1938, Jewish synagogues and businesses in Germany and Austria were attacked and hundreds of Jews arrested. This marked a new level of ferocity in the Nazis’ anti-Semitic policies. As European countries came under German occupation during World War II, Nazis applied anti-Jewish measures and established ghettos to confine Jewish populations. By the end of 1941, the Final Solution, the Nazi policy of extermi- nating all Jews, was in place and the mass deportations of Jews to the concentration camps had begun. HIDING Some Jews tried to escape by going into hiding. Few succeeded because only a small number of gentiles were willing to risk hiding Jews. Since hiding even one person was dangerous, children were often separated from their parents and siblings. Many parents had to make the painful decision to give their children over to complete strangers. Some children were sent to live with Christian families or placed in convents and orphanages. To survive, children often had to assume Christian identities, changing their names and histories in order to pass as non-Jews. -

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Re: Otto Frank File Embargoed Until

Prepared for: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Re: Otto Frank File Embargoed until: February 14, 2007 at 10 AM EST BACKGROUND TO THE SITUATION OF JEWS IN THE NETHERLANDS UNDER NAZI OCCUPATION AND OF THE FAMILY OF OTTO FRANK By: David Engel Greenberg Professor of Holocaust Studies New York University Understanding the situation of Jews in the Netherlands under Nazi occupation, like understanding any aspect of the Holocaust, requires suspension of hindsight. No one could know in 1933, 1938, or even early 1941 that the Nazi regime would soon embark upon a systematic program aimed at killing each and every Jewish man, woman, and child within its reach. The statement is true of top German officials no less than it is of the Jewish and non-Jewish civilian populations of the twenty countries within the Nazi orbit and of the governments and peoples of the Allied and neutral countries. Although it is tempting to look back upon the history of Nazi anti-Jewish utterances and measures and to detect in them an ostensible inner logic leading inexorably to mass murder, the consensus among historians today is that when the Nazi regime came to power in January 1933 it had no clear idea how the so-called Jewish problem might best be solved. It knew only that, from its perspective, Jews presented a problem that would need to be solved sooner or later, but finding a long-term solution was initially not one of the regime's most immediate priorities. Between 1933-41 various Nazi agencies proposed different schemes for dealing with Jews. -

Holocaust Education Teacher Resources Why Teach The

Holocaust Education Teacher Resources Compiled by Sasha Wittes, Holocaust Education Facilitator For Ilana Krygier Lapides, Director, Holocaust & Human Rights Education Calgary Jewish Federation Why Teach The Holocaust? The Holocaust illustrates how silence and indifference to the suffering of others, can unintentionally, serve to perpetuate the problem. It is an unparalleled event in history that brings to the forefront the horrors of racism, prejudice, and anti-Semitism, as well as the capacity for human evil. The Canadian education system should aim to be: democratic, non-repressive, humanistic and non-discriminating. It should promote tolerance and offer bridges for understanding of the other for reducing alienation and for accommodating differences. Democratic education is the backbone of a democratic society, one that fosters the underpinning values of respect, morality, and citizenship. Through understanding of the events, education surrounding the Holocaust has the ability to broaden students understanding of stereotyping and scapegoating, ensuring they become aware of some of the political, social, and economic antecedents of racism and provide a potent illustration of both the bystander effect, and the dangers posed by an unthinking conformity to social norms and group peer pressure. The study of the Holocaust coupled with Canada’s struggle with its own problems and challenges related to anti-Semitism, racism, and xenophobia will shed light on the issues facing our society. What was The Holocaust? History’s most extreme example of anti- Semitism, the Holocaust, was the systematic state sponsored, bureaucratic, persecution and annihilation of European Jewry by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1933-1945. The term “Holocaust” is originally of Greek origin, meaning ‘sacrifice by fire’ (www.ushmm.org). -

Holocaust Education Standards Grade 4 Standard 1: SS.4.HE.1

1 Proposed Holocaust Education Standards Grade 4 Standard 1: SS.4.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.4.HE.1.1 Compare and contrast Judaism to other major religions observed around the world, and in the United States and Florida. Grade 5 Standard 1: SS.5.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.5.HE.1.1 Define antisemitism as prejudice against or hatred of the Jewish people. Students will recognize the Holocaust as history’s most extreme example of antisemitism. Teachers will provide students with an age-appropriate definition of with the Holocaust. Grades 6-8 Standard 1: SS.68.HE.1. Foundations of Holocaust Education SS.68.HE.1.1 Define the Holocaust as the planned and systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of European Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945. Students will recognize the Holocaust as history’s most extreme example of antisemitism. Students will define antisemitism as prejudice against or hatred of Jewish people. Grades 9-12 Standard 1: SS.HE.912.1. Analyze the origins of antisemitism and its use by the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi) regime. SS.912.HE.1.1 Define the terms Shoah and Holocaust. Students will distinguish how the terms are appropriately applied in different contexts. SS.912.HE.1.2 Explain the origins of antisemitism. Students will recognize that the political, social and economic applications of antisemitism led to the organized pogroms against Jewish people. Students will recognize that The Protocols of the Elders of Zion are a hoax and utilized as propaganda against Jewish people both in Europe and internationally. -

Misconceptions

Misconceptions (from Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center) Norwegian non-Jews wore paper clips to express solidarity with Norwegian Jewry When the Germans occupied Norway in June 1940, between 1700 and 1800 Jews lived there – most of them in Oslo and all but 200 of them Norwegian citizens. Acceding to German demands, the collaborationist government immediately implemented anti-Jewish legislation. In November 1942, in response to further demands, the government rounded up more than 700 Jews, who were subsequently deported to Auschwitz where most were killed. Although the Norwegian resistance managed to smuggle the remaining Jews to neutral Sweden, the wearing of paper clips had nothing to do with demonstrating support for these efforts or solidarity with Norwegian Jewry. Rather, it represented one of many non-violent expressions of Norwegian nationalism and loyalty to King Haakon VII. These included listening secretly to foreign news broadcasts, printing and distributing underground newspapers and wearing pins fashioned from coins with the king’s head brightly polished, from various “flowers of loyalty,” from the symbol “H7” (for Haakon VII), and – for a time, after the latter were outlawed – from paper clips (also occasionally worn as bracelets). Why paper clips? Presumably – although some dispute this – because they were invented by a Norwegian named Johan Vaaler in 1899. Although, ironically, he had to patent the device in Germany because Norway had no patent law at the time. Vaaler did nothing more with his invention and, in subsequent years, paper clips would be manufactured and mass-marketed by firms in the United States and Great Britain (most notably, the Gem Company of Great Britain – originators of the familiar “double- U” slide-on clips, which the Norwegians may very well have worn.) The Germans used crushed Jewish bones to pave the Autobahn The Germans crushed Jewish bones in two specific contexts only. -

Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor (Also Called the Nuremberg Laws) — September 15, 1935 5

Lesson 10: Handout 1, Document 1 Laws Passed by Hitler and the Nazis Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor (also called the Nuremberg laws) — September 15, 1935 5 Firm in the knoWledge that the puritY of German blood is the basis for the surViVal of the German people and inspired bY the unshakeable determination to safeguard the future of the German nation, the Reichstag has unanimouslY resolVed upon the folloWing laW. Section 1 Marriages between Jews and citizens of German or some related blood are forbidden. Such marriages . are invalid, even if they take place abroad in order to avoid the law. Section 2 Sexual relations outside marriage between Jews and citizens of German or related blood are forbidden. Section 3 Jews will not be permitted to employ female citizens of German or related blood who are under 45 years as housekeepers. Section 4 1. Jews are forbidden to raise the national flag or display the national colors. 2. However, they are allowed to display the Jewish colors. The exercise of this right is protected by the State. Section 5 Anyone who disregards Section 1 . Section 2 . Sections 3 or 4 will be pun - ished with imprisonment up to one year or with a fine, or with one of these penalties. Purpose: To deepen understanding of the power of conformity and discrimination in Nazi Germany and in society today. • 150 Lesson 10: Handout 1, Document 2 Laws Passed by Hitler and the Nazis The Reich Citizenship Law (also called the Nuremberg laws) — September 15, 1935 Article 1 6 Section 2 1. -

Downloads/.Last Accessed: 9

Tracing and Documenting Nazi Victims Past and Present Arolsen Research Series Edited by the Arolsen Archives – International Center on Nazi Persecution Volume 1 Tracing and Documenting Nazi Victims Past and Present Edited by Henning Borggräfe, Christian Höschler and Isabel Panek On behalf of the Arolsen Archives. The Arolsen Archives are funded by the German Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media (BKM). ISBN 978-3-11-066160-6 eBook (PDF) ISBN 978-3-11-066537-6 eBook (EPUB) ISBN 978-3-11-066165-1 ISSN 2699-7312 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licens-es/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020932561 Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020 by the Arolsen Archives, Henning Borggräfe, Christian Höschler, and Isabel Panek, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: Jan-Eric Stephan Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Preface Tracing and documenting the victims of National Socialist persecution is atopic that has receivedlittle attention from historicalresearch so far.Inorder to take stock of existing knowledge and provide impetus for historicalresearch on this issue, the Arolsen Archives (formerlyknown as the International Tracing Service) organized an international conferenceonTracing and Documenting Victimsof Nazi Persecution: Historyofthe International Tracing Service (ITS) in Context. Held on October 8and 92018 in BadArolsen,Germany, this event also marked the seventieth anniversary of search bureaus from various European statesmeet- ing with the recentlyestablished International Tracing Service (ITS) in Arolsen, Germany, in the autumn of 1948. -

Lithuania and the Jews the Holocaust Chapter

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Lithuania and the Jews The Holocaust Chapter Symposium Presentations W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Lithuania and the Jews The Holocaust Chapter Symposium Presentations CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2004 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, July 2005 Copyright © 2005 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword.......................................................................................................................................... i Paul A. Shapiro and Carl J. Rheins Lithuanian Collaboration in the “Final Solution”: Motivations and Case Studies........................1 Michael MacQueen Key Aspects of German Anti-Jewish Policy...................................................................................17 Jürgen Matthäus Jewish Cultural Life in the Vilna Ghetto .......................................................................................33 David G. Roskies Appendix: Biographies of Contributors.........................................................................................45 Foreword Centuries of intellectual, religious, and cultural achievements distinguished Lithuania as a uniquely important center of traditional Jewish arts and learning. The Jewish community -

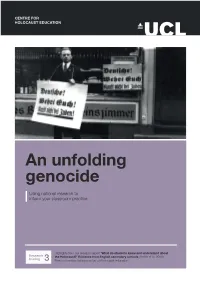

An Unfolding Genocide Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION An unfolding genocide Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016). briefing 3 Free to download at www.ucl.ac.uk/holocaust-education The Holocaust was not a single, monolithic event but a sequential process that developed and became radicalised over time. Why does this matter? If students are to understand that a genocide does not happen merely For students, building a detailed knowledge of the Holocaust’s chronology can enable them to see because someone wills it, it is important that they see how the development the underlying patterns and processes involved. It can allow them to identify key turning points and from persecution to genocide unfolded and evolved over time; that key understand why significant decisions were made in the context of each particular moment. This powerful decisions were taken by a range of individuals and agencies; and that the knowledge can help them to understand how extremist actions in a society can take root and develop. context of a European war was critical in shaping these decisions. This third briefing in our series reports on what English secondary school students know and understand about the chronology of the Holocaust, when it happened and how it developed. Closely linked, the next briefing examines students’ knowledge and understanding of where the Holocaust took place. So that students understand a genocide does not happen merely because of one person’s will, it is important that they see how the Holocaust unfolded over time; that decisions What do students know about were made by a range of different individuals; when the Holocaust happened? and that the people involved were influenced by the context of the unfolding war.