Conflict, Postconflict, and the Functions of the University: Lessons from Colombia and Other Armed Conflicts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Goldstein and Martha Moore Avery Papers 1870-1958 (Bulk 1917-1940) MS.1986.167

David Goldstein and Martha Moore Avery Papers 1870-1958 (bulk 1917-1940) MS.1986.167 http://hdl.handle.net/2345/4438 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Biographical note: David Goldstein .............................................................................................................. 6 Biographical note: Martha Moore Avery ...................................................................................................... 7 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................... 11 I: David Goldstein -

Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano

COLOMBIAN NATIONALISM: FOUR MUSICAL PERSPECTIVES FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO by Ana Maria Trujillo A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music The University of Memphis December 2011 ABSTRACT Trujillo, Ana Maria. DMA. The University of Memphis. December/2011. Colombian Nationalism: Four Musical Perspectives for Violin and Piano. Dr. Kenneth Kreitner, Ph.D. This paper explores the Colombian nationalistic musical movement, which was born as a search for identity that various composers undertook in order to discover the roots of Colombian musical folklore. These roots, while distinct, have all played a significant part in the formation of the culture that gave birth to a unified national identity. It is this identity that acts as a recurring motif throughout the works of the four composers mentioned in this study, each representing a different stage of the nationalistic movement according to their respective generations, backgrounds, and ideological postures. The idea of universalism and the integration of a national identity into the sphere of the Western musical tradition is a dilemma that has caused internal struggle and strife among generations of musicians and artists in general. This paper strives to open a new path in the research of nationalistic music for violin and piano through the analyses of four works written for this type of chamber ensemble: the third movement of the Sonata Op. 7 No.1 for Violin and Piano by Guillermo Uribe Holguín; Lopeziana, piece for Violin and Piano by Adolfo Mejía; Sonata for Violin and Piano No.3 by Luís Antonio Escobar; and Dúo rapsódico con aires de currulao for Violin and Piano by Andrés Posada. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Kirk Franklin Just For Me 5:11 2019 Gospel 182 Disk Local 2 Kanye West I Love It (Clean) 2:11 2019 Rap 4 128 Disk Closer To My Local 3 Drake 5:14 2014 Rap 3 128 Dreams (Clean) Disk Nellie Tager Local 4 If I Back It Up 3:49 2018 Soul 3 172 Travis Disk Local 5 Ariana Grande The Way 3:56 The Way 1 2013 RnB 2 190 Disk Drop City Yacht Crickets (Remix Local 6 5:16 T.I. Remix (Intro 2013 Rap 128 Club Intro - Clean) Disk In The Lonely I'm Not the Only Local 7 Sam Smith 3:59 Hour (Deluxe 5 2014 Pop 190 One Disk Version) Block Brochure: In This Thang Local 8 E40 3:09 Welcome to the 16 2012 Rap 128 Breh Disk Soil 1, 2 & 3 They Don't Local 9 Rico Love 4:55 1 2014 Rap 182 Know Disk Return Of The Local 10 Mann 3:34 Buzzin' 2011 Rap 3 128 Macc (Remix) Disk Local 11 Trey Songz Unusal 4:00 Chapter V 2012 RnB 128 Disk Sensual Local 12 Snoop Dogg Seduction 5:07 BlissMix 7 2012 Rap 0 201 Disk (BlissMix) Same Damn Local 13 Future Time (Clean 4:49 Pluto 11 2012 Rap 128 Disk Remix) Sun Come Up Local 14 Glasses Malone 3:20 Beach Cruiser 2011 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk I'm On One We the Best Local 15 DJ Khaled 4:59 2 2011 Rap 5 128 (Clean) Forever Disk Local 16 Tessellated Searchin' 2:29 2017 Jazz 2 173 Disk Rahsaan 6 AM (Clean Local 17 3:29 Bleuphoria 2813 2011 RnB 128 Patterson Remix) Disk I Luh Ya Papi Local 18 Jennifer Lopez 2:57 1 2014 Rap 193 (Remix) Disk Local 19 Mary Mary Go Get It 2:24 Go Get It 1 2012 Gospel 4 128 Disk LOVE? [The Local 20 Jennifer Lopez On the -

Toward the Thinking Curriculum: Current Cognitive Research

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 328 871 CS 009 714 AUTHOR Resnick, Lauren B., Ed.; Klopfer, Leopold E., Ed. TITLE Toward the Thinking Curriculum: Current Cognitive Research. 1989 ASCD Yearbook. INSTITUTION Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, Va. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87120-156-9; ISSN-1042-9018 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 231p. AVAILABLE FROMAssociation for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1250 N. Pitt St., Alexandria, VA 22314-1403 ($15.95). PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Collected Works - Serials (022) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Computer Assisted Instruction; *Critical Thinking; *Curriculum Development; Curriculum Research; Higher Education; Independent Reading; *Mathematics Instruction; Problem Solving; *Reading Comprehension; *Science Instruction; Writing Research IDENTIFIERS *Cognitive Research; Knowledge Acquisition ABSTRACT A project of the Center for the Study of Learning at the University of Pittsburgh, this yearbook combines the two major trends/concerns impacting the future of educational development for the next decade: knowledge and thinking. The yearbook comprises tLa following chapters: (1) "Toward the Thinking Curriculum: An Overview" (Lauren B. Resnick and Leopold E. Klopfer); (2) "Instruction for Self-Regulated Reading" (Annemarie Sullivan Palincsar and Ann L. Brown);(3) "Improving Practice through Jnderstanding Reading" (Isabel L. Beck);(4) "Teaching Mathematics Concepts" (Rochelle G. Kaplan and others); (5) "Teaching Mathematical Thinking and Problem Solving" (Alan H. Schoenfeld); (6) "Research on Writing: Building a Cognitive and Social Understanding of Composing" (Glynda Ann Hull); (7) "Teaching Science for Understanding" (James A. Minstrell); (8) "Research on Teaching Scientific ThInking: Implications for Computer-Based Instruction" (Jill H. Larkin and Ruth W. Chabay); and (9) "A Perspective on Cognitive Research and Its Implications for Instruction" (John D. -

Latam 2019 Press Release.Pages

2019 2018 Institution Country rank rank Pontifical Catholic University of Chile Chile 1 3 University of São Paulo Brazil 2 2 University of Campinas Brazil 3 1 Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) Brazil 4 7 Monterrey Institute of Technology Mexico 5 5 Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) Brazil 6 4 University of Chile Chile 7 6 Federal University of Minas Gerais Brazil 8 9 University of the Andes, Colombia Colombia 9 8 São Paulo State University (UNESP) Brazil 10 11 Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul Brazil 11 10 Federal University of Santa Catarina Brazil 12 14 Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Brazil 13 12 National Autonomous University of Mexico Mexico 14 13 University of Brasília Brazil 15 16 Federal University of São Carlos Brazil 16 15 Federal University of Viçosa Brazil 17 21 Metropolitan Autonomous University Mexico 18 26 Federal University of Ceará (UFC) Brazil 19 51–60 Pontifical Catholic University of Peru Peru =20 18 Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS) Brazil =20 33 National University of Colombia Colombia 22 31 Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso Chile 23 27 University of Santiago, Chile (USACH) Chile 24 23 Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia Peru 25 =41 Federal University of Paraná (UFPR) Brazil 26 36 Austral University Argentina 27 51–60 Pontifical Javeriana University Colombia 28 29 Federal University of Pernambuco Brazil 29 35 Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) Brazil 30 25 Federal University of Bahia Brazil 31 30 The University of the West Indies -

Ccl Frankfurt Englis

CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 2 The International Book Fair of Bogotá (FILBo for its acronym in Spanish) turns 31 in its next edition, which will take place from April 17th to May 2th, 2018. We want to celebrate not only the impressive growth of its academic program in recent years, which has had the participation of authors of extraordinary international relevance such as Literature Nobel prize recipients Svetlana Alexievich, Mario Vargas Llosa, and J.G.M. Le Clezio, but also the development of its international relevance such as Literature and, especially, our new Hall of Rights, a meeting place for agents, editors, and scouts interested in the Spanish-speaking publishing market. This catalog is a window to contemporary Colombian publishing. Throughout its pages you will find a series of recently published books of fiction, nonfiction, and children’s literature, all of which have their rights available for sale. The books shown in this catalog have been hand picked by Colombian publishers, with the aim of showcasing the best of their production. We are sure that here you will find something interesting as well in here you will find something that suits your interests. At the International Frankfurt Book Fair we not only celebrate the creation of the FILBo Hall of Rights as a new standard for the exchanging of rights during the first semester of the year in Latin America; we also want to showcase Bogotá as a literary and tourist destination: a city of books. CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 3 CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 4 CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 5 CATALOGUE OF BOOKS FROM COLOMBIA | 2017 | 6 University of La Sabana We are a publishing house whose sole purpose has been to publish the intellectual production of our teachers through different types formats such as books, magazines, brochures and manuals, as the result of their research made in the University, as well as any other other kind of texts or documents that could be of interest for our own community. -

Characterization of Students Admitted to Medical-Surgical Specializations

ISSN (Print) : 2319-8613 ISSN (Online) : 0975-4024 Virna Caraballo Osorio et al. / International Journal of Engineering and Technology (IJET) Characterization of students admitted to medical-surgical specializations at The University of Cartagena, 2016-2 Virna Caraballo Osorio #1, Rita Sierra Merlano #2, Marlene Duran Lengua #3 # School of Medicine, Universidad de Cartagena 130015 Cartagena de Indias, D. T. y C., Colombia 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected] 3 [email protected] Abstract—In Colombia there are currently few quotas to perform a surgical specialization, in comparison with the number of medical graduates. A descriptive study whose objective was to conduct a socio- demographic and academic-investigative characterization of students admitted to medical-surgical specializations at the University of Cartagena in 2016. Enrolled a total of 1420 doctors who competed for 55 quotas available in twelve medical-surgical specializations. Evaluated scores on the test of knowledge, resume and interview of the admitted 55 (3.8% of the total) and was also carried out a survey which included socio-demographic aspects. The maximum score of the knowledge test was 61 (of 80 possible) which represents 76.25% of the total. With regard to the rating of the resume were admitted with scores of 1.3 points, the average resumes was 4.79. The interview scores were higher with an average of 9.39 (of 10 possible). The most preferred medical specialty was internal medicine (21.8%) 12.74% compared to 9.06% in men and women respectively, followed by pediatrics (14.5%), women were inclined for Internal Medicine and Pediatrics and did not enroll in any specialty of Neurosurgery, Orthopedics and traumatology and General Surgery. -

CLAR Latin American Reference Credit the Tuning Project Is Subsidised by the European Commision

CLAR Latin American Reference Credit The Tuning project is subsidised by the European Commision. This publication refl ects only the opinion of its authors. The European Commission may not be held responsible for any use made of the information contained herein. Although all the material developed as part of the Tuning – Latin America project is the property of its formal participants, other institutions of higher education are free to test and make use of this material subsequent to its publication on condition that the source is acknowledged. © Tuning Project http://www.tuningal.org/ No part of this publication, including the cover design, may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any electronic, chemical, mechanical or optic medium, of recording or photocopying, without the permission of the publisher. Design: © LIT Images © Publicaciones de la Universidad de Deusto Apartado 1 - 48080 Bilbao e-mail: [email protected] Legal Deposit: BI-5569-201369-2013 Tuning Latin America Project CLAR Latin American Reference Credit 2013 University of Deusto Bilbao Tuning Latin America Project This document was prepared and agreed upon within the framework of Tuning Latin America by representatives from the following uni- versities and bodies in charge of higher education participating in the project: Argentina: University of Buenos Aires, National University of Cór- doba, National University of La Plata, National University of Rosario, National University of Cuyo, National Technological University, Na- tional University of the Littoral, National University of the South, National University of San Juan, National University of San Luis, Na- tional University of the North-East, National University of Río Cuarto, National University of Jujuy, National University of Lanús, National Uni- versity of the Centre of the Province of Buenos Aires, National Univer- sity of the North-West of the Province of Buenos Aires, National Uni- versity of Third of February, CEMIC Institute, National Inter-University Council, University Policy Bureau. -

Colombian Composer Adolfo Mejia, Four Works for Small Ensembles

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2017 Colombian Composer Adolfo Mejia, Four Works for Small Ensembles Alvaro Jose Angulo Julio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Angulo Julio, Alvaro Jose, "Colombian Composer Adolfo Mejia, Four Works for Small Ensembles" (2017). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4214. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4214 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. COLOMBIAN COMPOSER ADOLFO MEJIA, FOUR WORKS FOR SMALL ENSEMBLES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Alvaro Jose Angulo Julio B.M., National University of Colombia, 2009 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2013 May 2017 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to express my great gratitude to Dennis Parker, for being not only my professor but also for enabling the ways to develop my career and dreams in Louisiana. Thanks to Dr. Delony and Maestro Riazuelo for their clear guidance in Jazz and Orchestral Studies, respectively, and for their constant invitation to have a wider vision to play music. Thanks to Manuel Mejía, Enrique Muñoz, and Miroslav Swoboda for sharing their stories, documents and thoughts about the composer, their information served as constant motivation during the entire investigation. -

Southern White Student Activists in the Civil Rights Movement

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2020 Not Accepting the Status Quo: Southern White Student Activists in the Civil Rights Movement Ashton Ryan Cooper University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Cooper, Ashton Ryan, "Not Accepting the Status Quo: Southern White Student Activists in the Civil Rights Movement. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2020. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ashton Ryan Cooper entitled "Not Accepting the Status Quo: Southern White Student Activists in the Civil Rights Movement." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Higher Education Administration. Dorian L. McCoy, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Karen D. Boyd, Jud C. Laughter, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Not Accepting the Status Quo: Southern White Student Activists in the Civil Rights Movement A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Ashton Ryan Cooper May 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Ashton Ryan Cooper All rights reserved. -

The Antiwar Dilemma of the Farmer-Labor Party

Mr. Garlid is assistant professor of history at Wisconsin State University — River Falls. This article is from his doctoral dissertation on "Politics in Minnesota and American Foreign Relations: 1921-1941." The ANTIWAR DILEMMA of the FARMER-LABOR PARTY GEORGE W. GARLID WRITING IN 1946, Eric Sevareid recap often were, in the words of Reinhold Nie tured the atmosphere of his years as a stu buhr, complacent "about evils, remote from dent at the University of Minnesota. He our lives."- Finally, they were years when described the world view that he had shared the revisionist thesis won its widest accept with other liberals during the middle thir ance. ties. Most revealing is his profound sense of Sevareid and his fellow students were having been caught up in a historical per ashamed that their fathers and uncles had spective which later he could neither accept accepted the official propaganda during nor explain.^ World War I. Many took the Oxford oath; For many Minnesotans the 1930s were still others agitated to end compulsory mili years when convictions concerning world af tary drill at the university. Sevareid recalled fairs were held dogmatically. They were a campus meeting at which the antiwar oath years when occasionally these convictions was debated wildly by two or three hundred were undermined and gradually altered. students. A vote of those assembled indi They were years when the all-pervasive cated nearly unanimous approval. In 1934, commitment to peace made impermanent after a week of antiwar agitation at Carle allies of individuals clinging to disparate ton College, four hundred students voted views. -

GTOAA Membership Application Form

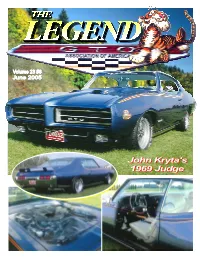

IN THIS ISSUE Volume 23 Number 6 June 2005 1 Officer & Staff Info 2 First Gear Tom Szymczyk 3 Notes From The Prez GTO Mailbag 4 20 Years Ago Today Bob Alexander Golden Quill Awards Cover Car Features 5 An Icon Passes As I write this in late April, Old It is no secret that Jim Stern, Feature John Sawruk Cars Weekly has just announced the Editor for this publication, keeps a work- winners of the “Golden Quill Awards” ing cover car feature backlog. This is 6 American Dream Maker for 2004. Former Legend editor Beth the best way he can avoid last minute Bill McCoy Butcher won for the umpteenth time for scrambling when faced with a publica- her work on this publication, a well- tion deadline each month. There are also 7 Original Time Machine Stan Kaminski deserved accolade for her many years of circumstances beyond his control which service to the GTOAA in that position. sometimes conspire to push back fea- 8 At The Auction Some of our local chapters also re- tures he submits (National Convention Chuck Catalano ceived the “Golden Quill” for 2004. coverage and the Roster Issue for exam- 9 Chapter Affairs Dept. Speaking of umpteen wins, Land of ple). Publication delays may result and John Johnson Lakes GTOs won again for Tiger Times, Jim knows these can be frustrating when with Dick Kos as editor. Another peren- you are waiting for your feature to ap- 10 Chapter Directory nial favorite, Tiger News, from the pear. Hopefully, seeing your GTO on Cruisin’ Tigers GTO Club garnered an the cover of The Legend will make the 12 Cover Car Feature John Kryta award for Paul Weinstein as editor.