H17 the Descent of Birds < Neornithines, Archaeopteryx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript

Page 1 Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript Narrator: For more than a century, Americans have had a love affair with dinosaurs. Extinct for millions of years, they were barely known until giant, fossil bones were discovered in the mid-nineteenth century. Two American scientists, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, led the way to many of these discoveries, at the forefront of the young field of paleontology. Jacques Gauthier, Paleontologist: Every iconic dinosaur every kid grows up with, apatosaurus, triceratops, stegosaurus, allosaurus, these guys went out into the American West and they found that stuff. Narrator: Cope and Marsh shed light on the deep past in a way no one had ever been able to do before. They unearthed more than 130 dinosaur species and some of the first fossil evidence supporting Darwin’s new theory of evolution. Mark Jaffe, Writer: Unfortunately there was a more sordid element, too, which was their insatiable hatred for each other, which often just baffled and exasperated everyone around them. Peter Dodson, Paleontologist: They began life as friends. Then things unraveled… and unraveled in quite a spectacular way. Narrator: Cope and Marsh locked horns for decades, in one of the most bitter scientific rivalries in American history. Constantly vying for leadership in their young field, they competed ruthlessly to secure gigantic bones in the American West. They put American science on the world stage and nearly destroyed one another in the process. Page 2 In the summer of 1868, a small group of scientists boarded a Union Pacific train for a sightseeing excursion through the heart of the newly-opened American West. -

Insight Into the Evolution of Avian Flight from a New Clade of Early

J. Anat. (2006) 208, pp287–308 IBlackwnell Publishing sLtd ight into the evolution of avian flight from a new clade of Early Cretaceous ornithurines from China and the morphology of Yixianornis grabaui Julia A. Clarke,1 Zhonghe Zhou2 and Fucheng Zhang2 1Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Abstract In studies of the evolution of avian flight there has been a singular preoccupation with unravelling its origin. By con- trast, the complex changes in morphology that occurred between the earliest form of avian flapping flight and the emergence of the flight capabilities of extant birds remain comparatively little explored. Any such work has been limited by a comparative paucity of fossils illuminating bird evolution near the origin of the clade of extant (i.e. ‘modern’) birds (Aves). Here we recognize three species from the Early Cretaceous of China as comprising a new lineage of basal ornithurine birds. Ornithurae is a clade that includes, approximately, comparatively close relatives of crown clade Aves (extant birds) and that crown clade. The morphology of the best-preserved specimen from this newly recognized Asian diversity, the holotype specimen of Yixianornis grabaui Zhou and Zhang 2001, complete with finely preserved wing and tail feather impressions, is used to illustrate the new insights offered by recognition of this lineage. Hypotheses of avian morphological evolution and specifically proposed patterns of change in different avian locomotor modules after the origin of flight are impacted by recognition of the new lineage. -

Phylocode: a Phylogenetic Code of Biological Nomenclature

PhyloCode: A Phylogenetic Code of Biological Nomenclature Philip D. Cantino and Kevin de Queiroz (equal contributors; names listed alphabetically) Advisory Group: William S. Alverson, David A. Baum, Harold N. Bryant, David C. Cannatella, Peter R. Crane, Michael J. Donoghue, Torsten Eriksson*, Jacques Gauthier, Kenneth Halanych, David S. Hibbett, David M. Hillis, Kathleen A. Kron, Michael S. Y. Lee, Alessandro Minelli, Richard G. Olmstead, Fredrik Pleijel*, J. Mark Porter, Heidi E. Robeck, Greg W. Rouse, Timothy Rowe*, Christoffer Schander, Per Sundberg, Mikael Thollesson, and Andre R. Wyss. *Chaired a committee that authored a portion of the current draft. Most recent revision: April 8, 2000 1 Table of Contents Preface Preamble Division I. Principles Division II. Rules Chapter I. Taxa Article 1. The Nature of Taxa Article 2. Clades Article 3. Hierarchy and Rank Chapter II. Publication Article 4. Publication Requirements Article 5. Publication Date Chapter III. Names Section 1. Status Article 6 Section 2. Establishment Article 7. General Requirements Article 8. Registration Chapter IV. Clade Names Article 9. General Requirements for Establishment of Clade Names Article 10. Selection of Clade Names for Establishment Article 11. Specifiers and Qualifying Clauses Chapter V. Selection of Accepted Names Article 12. Precedence Article 13. Homonymy Article 14. Synonymy Article 15. Conservation Chapter VI. Provisions for Hybrids Article 16. Chapter VII. Orthography Article 17. Orthographic Requirements for Establishment Article 18. Subsequent Use and Correction of Established Names Chapter VIII. Authorship of Names Article 19. Chapter IX. Citation of Authors and Registration Numbers Article 20. Chapter X. Governance Article 21. Glossary Table 1. Equivalence of Nomenclatural Terms Appendix A. -

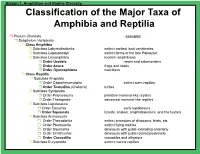

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are -

Phylonyms; a Companion to the Phylocode

Pan-Lepidosauria J. A. Gauthier and K. de Queiroz, new clade name Registration Number: 118 2009; Evans and Borsuk-Bialylicka, 2009; Evans and Jones, 2010; but see Müller, 2004; De!nition: !e total clade of the crown clade Jones et al., 2013). More recently, kuehneosaurs Lepidosauria. !is is a crown-based total-clade have been inferred to be stem archosaurs close de"nition. Abbreviated de"nition: total ∇ of to Trilophosaurus buettneri by Pritchard and Lepidosauria. Nesbitt (2017), although Simões et al. (2018) placed them as either stem saurians or stem Etymology: Derived from pan (Greek), here archosaurs depending on the analysis, but in referring to “pan-monophylum,” another term either case only distantly related to T. buettneri. for “total clade,” and Lepidosauria, the name !e Early Triassic Sophineta cracoviensis and the of the corresponding crown clade; hence, “the Middle Jurassic Marmoretta oxoniensis have been total clade of Lepidosauria.” more consistently regarded as stem lepidosaurs, although that inference depends upon cor- Reference Phylogeny: Gauthier et al. (1988) rect association among disarticulated remains Figure 13, where the clade in question is named (Evans, 1991; Waldman and Evans, 1994; Lepidosauromorpha and is hypothesized to Evans, 2009; Evans and Borsuk-Bialylicka, include Younginiformes, which is no longer con- 2009; Evans and Jones, 2010; Jones et al., 2013; sidered part of the clade (see Composition). Renesto and Bernardi, 2014). Depending on the analysis, Simões et al. (2018) inferred S. Composition: Pan-Lepidosauria is composed cracoviensis to be either a stem lepidosaurian of Lepidosauria (Pan-Sphenodon plus Pan- or a stem squamatan, but they consistently Squamata, see entry in this volume) and all inferred M. -

New Developmental Evidence Clarifies the Evolution of Wrist Bones in the Dinosaur–Bird Transition

New Developmental Evidence Clarifies the Evolution of Wrist Bones in the Dinosaur–Bird Transition Joa˜o Francisco Botelho, Luis Ossa-Fuentes, Sergio Soto-Acun˜ a, Daniel Smith-Paredes, Daniel Nun˜ ez-Leo´ n, Miguel Salinas-Saavedra, Macarena Ruiz-Flores, Alexander O. Vargas* Laboratorio de Ontogenia y Filogenia, Departamento de Biologı´a, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile Abstract From early dinosaurs with as many as nine wrist bones, modern birds evolved to develop only four ossifications. Their identity is uncertain, with different labels used in palaeontology and developmental biology. We examined embryos of several species and studied chicken embryos in detail through a new technique allowing whole-mount immunofluores- cence of the embryonic cartilaginous skeleton. Beyond previous controversy, we establish that the proximal–anterior ossification develops from a composite radiale+intermedium cartilage, consistent with fusion of radiale and intermedium observed in some theropod dinosaurs. Despite previous claims that the development of the distal–anterior ossification does not support the dinosaur–bird link, we found its embryonic precursor shows two distinct regions of both collagen type II and collagen type IX expression, resembling the composite semilunate bone of bird-like dinosaurs (distal carpal 1+distal carpal 2). The distal–posterior ossification develops from a cartilage referred to as ‘‘element x,’’ but its position corresponds to distal carpal 3. The proximal–posterior ossification is perhaps most controversial: It is labelled as the ulnare in palaeontology, but we confirm the embryonic ulnare is lost during development. Re-examination of the fossil evidence reveals the ulnare was actually absent in bird-like dinosaurs. -

Second Meeting of the International Society for Phylogenetic Nomenclature Yale University New Haven, June 28 – July 2, 2006

Second Meeting of the International Society for Phylogenetic Nomenclature Yale University New Haven, June 28 – July 2, 2006 PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Nico Cellinese, Co-Chair, Yale University Walter Joyce, Co-Chair, Program Officer, Yale University Michael Donoghue, Co-Host, Yale University Jacques Gauthier, Co-Host, Yale University David Baum, University of Wisconsin, Madison Philip Cantino, Ohio University Michel Laurin, CNRS, Paris Kevin de Queiroz, Smithsonian Institution CONTACT INFORMATION AT THE MEETING Nico Cellinese Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University 170 Whitney Avenue, PO Box 208118, New Haven, Connecticut, 06511, U.S.A Email: [email protected]; Tel. 203-432-3537 Walter Joyce Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University 170 Whitney Avenue, PO Box 208118, New Haven, Connecticut, 06511, U.S.A Email: [email protected]; Tel. 203-432-3748 OFFICIAL CONFERENCE VENUE On site registration, regular sessions, symposia, and the ISPN business meeting will be held in Linsly-Chittenden Hall at 63 High Street, New Haven. This beautifully restored venue is situated on Yale University’s Old Campus and thus easy walking distance from all downtown accommodations recommended by the ISPN Program Committee (see map for directions). ICEBREAKER The icebreaker will be held on June 28, 2006 starting at 7:00pm at BAR on 254 Crown Street, New Haven (see map for directions). TOUR OF THE PEABODY COLLECTIONS Conference attendants will have the opportunity to follow behind the scenes tours to a number of Peabody Collections during the late afternoon on July 1, 2006. Highlights include O.C. Marsh’s historic dinosaur collections and modern storage rooms in the new Environmental Science Facility. -

The Auk a Quarterly Journal of Ornithology Vol

The Auk A Quarterly Journal of Ornithology Vol. 119 No. 1 January 2002 The Auk 119(1):1±17, 2002 PERSPECTIVES IN ORNITHOLOGY WHY ORNITHOLOGISTS SHOULD CARE ABOUT THE THEROPOD ORIGIN OF BIRDS RICHARD O. P RUM1 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA OVER THE LAST 25 years, few topics in sys- for the evolution of birds and feathers (e.g. Bock tematics and paleontology have been as divi- 1965). sively debated as the origin of birds (Padian In 1974, John Ostrom (1974) challenged the and Chiappe 1998; Feduccia 1999a, b; Dalton status quo by revitalizing the old hypothesis 2000). For most of the middle of the twentieth that birds were related to dinosaurs (Huxley century, G. Heilmann's (1926) monumental 1868, 1870; Williston 1879) or, more speci®cally, analysis of the topic reigned unchallenged. to a group of the meat-eating theropod dino- Heilmann established de®nitively that birds saurs, represented by Deinonychus which he are members of the Archosauria (the large rep- had recently described. Jacques Gauthier (1986) tilian clade that also includes crocodiles, ptero- subsequently con®rmed that birds were a lin- saurs, and dinosaurs). But Heilmann was un- eage of theropod dinosaurs most closely relat- able to accept the voluminous evidence he ed to dromaeosaurs (the lineage now common- gathered that placed birds within the carnivo- ly known as ``raptors''), and that result has rous theropod dinosaurs because theropods been generally con®rmed by subsequent work- apparently lacked a furcula, and Heilmann be- ers (Gauthier et al. -

International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature Version 4C

International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature Version 4c Philip D. Cantino and Kevin de Queiroz (equal contributors; names listed alphabetically) In consultation with: Committee on Phylogenetic Nomenclature (2009–2010): Brian Andres, Tom Artois, Harold N. Bryant, Philip D. Cantino, Julia A. Clarke, Jacques A. Gauthier, Walter Joyce, Michael Keesey, Michel Laurin, David Marjanović, Kevin Padian, and David Tank. Additional members of the initial advisory group and Committee on Phylogenetic Nomenclature for earlier versions: William S. Alverson, David A. Baum, Christopher A. Brochu, David C. Cannatella, Peter R. Crane, Benoît Dayrat, Kevin de Queiroz, Michael J. Donoghue, Torsten Eriksson, Kenneth Halanych, David S. Hibbett, Kathleen A. Kron, Michael S. Y. Lee, Alessandro Minelli, Brent D. Mishler, Gerry Moore, Richard G. Olmstead, Fredrik Pleijel, J. Mark Porter, Greg W. Rouse, Timothy Rowe, Christoffer Schander, Per Sundberg, Mikael Thollesson, Mieczyslaw Wolsan, and André R. Wyss. Most recent revision: January 12, 2010 1 Table of Contents Preface 3 Preamble 26 Division I. Principles 27 Division II. Rules 28 Chapter I. Taxa 28 Article 1. The Nature of Taxa 28 Article 2. Clades 28 Article 3. Hierarchy and Rank 30 Chapter II. Publication 31 Article 4. Publication Requirements 31 Article 5. Publication Date 31 Chapter III. Names 32 Section 1. Status 32 Article 6 32 Section 2. Establishment 33 Article 7. General Requirements 33 Article 8. Registration 34 Chapter IV. Clade Names 36 Article 9. General Requirements for Establishment of Clade Names 36 Article 10. Selection of Clade Names for Establishment 42 Article 11. Specifiers and Qualifying Clauses 48 Chapter V. Selection of Accepted Names 57 Article 12. -

1 Excerpted by Permission from Chapter 9 of the Mistaken

Excerpted by permission from Chapter 9 of The Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W. H. Freeman and Co., 1998, 332pp. Chapter 9 Living Dinosaurs? Now, let us be quick to clarify our query. We're not talking about dinosaurs still living hidden in the black waters of Loch Nesse or the darkest jungles of Africa. All but a few crackpots admit that sauropods and plesiosaurs are really extinct. But what about dinosaurs living in your own back yard? It seemed ridiculous. Or so we thought as we packed up our books and moved to Berkeley. When we arrived we were met by the prospect of living dinosaurs, and it seemed surprising to be confronted with the argument by members of our own department, instead of the street-life of Telegraph Avenue. Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops obviously did disappear at the end of the Cretaceous, our new colleagues conceded. Nonetheless, one lineage that descended from the ancestral dinosaur survived the impact and eruptions at the K-T boundary. Today, that lineage is represented by over 9,000 species of birds. Furthermore, if birds are living descendants of dinosaurs, isn't it incorrect to say that dinosaurs are extinct? What does it mean to say birds are dinosaurs? Proponents argued that newly discovered fossils demonstrated that dinosaurs were the ancestors of birds. In addition, new methods for reconstructing evolutionary history and establishing evolutionary 1 relationships were being developed. Applying these methods to the fossil record resurrected dinosaurs from extinction and in effect changed the course of the history of life. -

Gauthier, J.A., Kearney, M., Maisano, J.A., Rieppel, O., Behlke, A., 2012

Assembling the Squamate Tree of Life: Perspectives from the Phenotype and the Fossil Record Jacques A. Gauthier,1 Maureen Kearney,2 Jessica Anderson Maisano,3 Olivier Rieppel4 and Adam D.B. Behlke5 1 Corresponding author: Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, P.O. Box 208109, New Haven CT 06520-8109 USA and Divisions of Vertebrate Paleontology and Vertebrate Zoology, Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208118, New Haven CT 06520-8118 USA —email: [email protected] 2 Division of Environmental Biology, National Science Foundation, Arlington VA 22230 USA 3 Jackson School of Geosciences, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin TX 78712 USA 4 Department of Geology, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605-2496 USA 5 Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, P.O. Box 208109, New Haven CT 06520-8109 USA Abstract We assembled a dataset of 192 carefully selected species—51 extinct and 141 extant—and 976 apo- morphies distributed among 610 phenotypic characters to investigate the phylogeny of Squamata (“lizards,” including snakes and amphisbaenians). These data enabled us to infer a tree much like those derived from previous morphological analyses, but with better support for some key clades. There are also several novel elements, some of which pose striking departures from traditional ideas about lizard evolution (e.g., that mosasaurs and polyglyphanodontians are on the scleroglos- san stem, rather than parts of the crown, and related to varanoids and teiids, respectively). Long- bodied, limb-reduced, “snake-like” fossorial lizards—most notably dibamids, amphisbaenians and snakes—have been and continue to be the chief source of character conflict in squamate morpho- logical phylogenetics. -

Chapter 14, the Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W

Chapter 14, The Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W. H. Freeman, 1998. Chapter 14 The Road to Jurassic Park As graduate students, it seemed that Archaeopteryx was the sole source of information about early bird evolution. Our textbooks said little about other Mesozoic birds because there wasn’t much known about them. Avian history was a dark and murky for a span of 85 million years following Archaeopteryx, and not until the beginning of the Tertiary did the trail of fossils leading toward today’s birds resume. Suddenly, an explosion of new discoveries has illuminated the darkness. In the last fifteen years, new Mesozoic birds have been collected in many parts of the world. South America, Spain, and Asia, are producing a wealth of new Cretaceous fossils, including complete skeletons of mature birds, entire nests of eggs, embryonic skeletons, and as we saw in the last chapter there are new fossils preserving feathers. With every professional paleontological meeting, it seems, someone announces a new Mesozoic bird. Others bring pictures or specimens representing new species, but show them only to a privileged few. Thanks to the press, the new discoveries are feeding rumors and excitement on a global scale, as the growing league of bird-watchers race to add one of the rarest species to their “life list”--a Mesozoic bird. Through the blinding flash of new discoveries, the Mesozoic roots of bird evolution are dimly coming in to focus, and what was terra incognita in our student days is now crossed by a several major highways (fig.