Chapter 14, the Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript

Page 1 Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript Narrator: For more than a century, Americans have had a love affair with dinosaurs. Extinct for millions of years, they were barely known until giant, fossil bones were discovered in the mid-nineteenth century. Two American scientists, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, led the way to many of these discoveries, at the forefront of the young field of paleontology. Jacques Gauthier, Paleontologist: Every iconic dinosaur every kid grows up with, apatosaurus, triceratops, stegosaurus, allosaurus, these guys went out into the American West and they found that stuff. Narrator: Cope and Marsh shed light on the deep past in a way no one had ever been able to do before. They unearthed more than 130 dinosaur species and some of the first fossil evidence supporting Darwin’s new theory of evolution. Mark Jaffe, Writer: Unfortunately there was a more sordid element, too, which was their insatiable hatred for each other, which often just baffled and exasperated everyone around them. Peter Dodson, Paleontologist: They began life as friends. Then things unraveled… and unraveled in quite a spectacular way. Narrator: Cope and Marsh locked horns for decades, in one of the most bitter scientific rivalries in American history. Constantly vying for leadership in their young field, they competed ruthlessly to secure gigantic bones in the American West. They put American science on the world stage and nearly destroyed one another in the process. Page 2 In the summer of 1868, a small group of scientists boarded a Union Pacific train for a sightseeing excursion through the heart of the newly-opened American West. -

H17 the Descent of Birds < Neornithines, Archaeopteryx

LIFE OF THE MESOZOIC ERA 465 h17 The descent of birds < neornithines, Archaeopteryx, Solnhofen Lms > Alfred, Lord Tennyson / once solved an enigma: When is an / eider [a seaduck] most like a merganser [a lake and river duck]? / He lived long enough to forget the answer. —an anonymous clerihew.1 All eighteen species of penguin live in the Southern Hemisphere. ... The descendants of a common ancestor, sharing common ground. ... ‘This bond, on my [Darwin’s] theory, is simple inheritance.’2 Bird evolution during the Cenozoic has been varied and rapid in the beak but not in the body. For example, Hawaiian Island bird arrivals beginning 5 Ma (million years ago) have evolved to new species with beaks specialized to feed on various flowers and seeds but their bodies have changed so little that the various pioneer-bird stocks are easy to identify. With that perspective, bird varieties distinctive in the beak as owls, hawks, penguins, ducks, flamingos, and parrots, are likely to have diverged in very ancient times. Ducks, albeit primitive ones such as web footed Presbyornis, which could wade but not paddle, already existed in the bird diversity of the Eocene when giant “terror birds,” such as Diatrema, patrolled the ground. Feathers are made mostly of beta keratin, a strong light-weight material. Bird feathers are modified scales which extrude from cells that line skin follicles. The shape and color of the feather so formed can change during the birds growth (say, a downy feather in youth and a stiff feather in adulthood) and by seasonal molts (say, a white feather in the winter and a colored feather for times of courting).3 All birds of the Cenozoic (30 orders) are characterized by toothless jaws and have a pair of elongated foot bones that are partially fused from the bottom up. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

Chapter 10, the Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W

Chapter 10, The Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W. H. Freeman, 1998. CHAPTER 10 Dinosaurs Challenge Evolution Enter Sir Richard Owen More than 150 years ago, the great British naturalist Richard Owen (fig. 10.01) ignited the controversy that Deinonychus would eventually inflame. The word "dinosaur" was first uttered by Owen in a lecture delivered at Plymouth, England in July of 1841. He had coined the name in a report on giant fossil reptiles that were discovered in England earlier in the century. The root, Deinos, is usually translated as "terrible" but in his report, published in 1842, Owen chose the words "fearfully great"1. To Owen, dinosaurs were the fearfully great saurian reptiles, known only from fossil skeletons of huge extinct animals, unlike anything alive today. Fig. 10.01 Richard Owen as, A) a young man at about the time he named Dinosauria, B) in middle age, near the time he described Archaeopteryx, and C) in old age. Dinosaur bones were discovered long before Owen first spoke their name, but no one understood what they represented. The first scientific report on a dinosaur bone belonging was printed in 1677 by Rev. Robert Plot in his work, The Natural History of Oxfordshire. This broken end of a thigh bone, came to Plot's attention during his research. It was nearly 60 cm in circumference--greater than the same bone in an elephant (fig.10.02). We now suspect that it belonged to Megalosaurus bucklandii, a carnivorous dinosaur now known from Oxfordshire. But Plot concluded that it "must have been a real Bone, now petrified" and that it resembled "exactly the figure of the 1 Chapter 10, The Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W. -

The Geology, Paleontology and Paleoecology of the Cerro Fortaleza Formation

The Geology, Paleontology and Paleoecology of the Cerro Fortaleza Formation, Patagonia (Argentina) A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Victoria Margaret Egerton in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 © Copyright 2011 Victoria M. Egerton. All Rights Reserved. ii Dedications To my mother and father iii Acknowledgments The knowledge, guidance and commitment of a great number of people have led to my success while at Drexel University. I would first like to thank Drexel University and the College of Arts and Sciences for providing world-class facilities while I pursued my PhD. I would also like to thank the Department of Biology for its support and dedication. I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Kenneth Lacovara, for his guidance and patience. Additionally, I would like to thank him for including me in his pursuit of knowledge of Argentine dinosaurs and their environments. I am also indebted to my committee members, Dr. Gail Hearn, Dr. Jake Russell, Dr. Mike O‘Connor, Dr. Matthew Lamanna, Dr. Christopher Williams and Professor Hermann Pfefferkorn for their valuable comments and time. The support of Argentine scientists has been essential for allowing me to pursue my research. I am thankful that I had the opportunity to work with such kind and knowledgeable people. I would like to thank Dr. Fernando Novas (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales) for helping me obtain specimens that allowed this research to happen. I would also like to thank Dr. Viviana Barreda (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales) for her allowing me use of her lab space while I was visiting Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. -

New Perspectives on Pterosaur Palaeobiology

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 24, 2021 New perspectives on pterosaur palaeobiology DAVID W. E. HONE1*, MARK P. WITTON2 & DAVID M. MARTILL2 1Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E14NS, UK 2School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Portsmouth, Burnaby Road, Portsmouth PO1 3QL, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Pterosaurs were the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight and occupied the skies of the Mesozoic for 160 million years. They occurred on every continent, evolved their incredible pro- portions and anatomy into well over 100 species, and included the largest flying animals of all time among their ranks. Pterosaurs are undergoing a long-running scientific renaissance that has seen elevated interest from a new generation of palaeontologists, contributions from scientists working all over the world and major advances in our understanding of their palaeobiology. They have espe- cially benefited from the application of new investigative techniques applied to historical speci- mens and the discovery of new material, including detailed insights into their fragile skeletons and their soft tissue anatomy. Many aspects of pterosaur science remain controversial, mainly due to the investigative challenges presented by their fragmentary, fragile fossils and notoriously patchy fossil record. With perseverance, these controversies are being resolved and our understand- ing of flying reptiles is increasing. This volume brings together a diverse set of papers on numerous aspects of the biology of these fascinating reptiles, including discussions of pterosaur ecology, flight, ontogeny, bony and soft tissue anatomy, distribution and evolution, as well as revisions of their taxonomy and relationships. -

Insight Into the Evolution of Avian Flight from a New Clade of Early

J. Anat. (2006) 208, pp287–308 IBlackwnell Publishing sLtd ight into the evolution of avian flight from a new clade of Early Cretaceous ornithurines from China and the morphology of Yixianornis grabaui Julia A. Clarke,1 Zhonghe Zhou2 and Fucheng Zhang2 1Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Abstract In studies of the evolution of avian flight there has been a singular preoccupation with unravelling its origin. By con- trast, the complex changes in morphology that occurred between the earliest form of avian flapping flight and the emergence of the flight capabilities of extant birds remain comparatively little explored. Any such work has been limited by a comparative paucity of fossils illuminating bird evolution near the origin of the clade of extant (i.e. ‘modern’) birds (Aves). Here we recognize three species from the Early Cretaceous of China as comprising a new lineage of basal ornithurine birds. Ornithurae is a clade that includes, approximately, comparatively close relatives of crown clade Aves (extant birds) and that crown clade. The morphology of the best-preserved specimen from this newly recognized Asian diversity, the holotype specimen of Yixianornis grabaui Zhou and Zhang 2001, complete with finely preserved wing and tail feather impressions, is used to illustrate the new insights offered by recognition of this lineage. Hypotheses of avian morphological evolution and specifically proposed patterns of change in different avian locomotor modules after the origin of flight are impacted by recognition of the new lineage. -

Phylocode: a Phylogenetic Code of Biological Nomenclature

PhyloCode: A Phylogenetic Code of Biological Nomenclature Philip D. Cantino and Kevin de Queiroz (equal contributors; names listed alphabetically) Advisory Group: William S. Alverson, David A. Baum, Harold N. Bryant, David C. Cannatella, Peter R. Crane, Michael J. Donoghue, Torsten Eriksson*, Jacques Gauthier, Kenneth Halanych, David S. Hibbett, David M. Hillis, Kathleen A. Kron, Michael S. Y. Lee, Alessandro Minelli, Richard G. Olmstead, Fredrik Pleijel*, J. Mark Porter, Heidi E. Robeck, Greg W. Rouse, Timothy Rowe*, Christoffer Schander, Per Sundberg, Mikael Thollesson, and Andre R. Wyss. *Chaired a committee that authored a portion of the current draft. Most recent revision: April 8, 2000 1 Table of Contents Preface Preamble Division I. Principles Division II. Rules Chapter I. Taxa Article 1. The Nature of Taxa Article 2. Clades Article 3. Hierarchy and Rank Chapter II. Publication Article 4. Publication Requirements Article 5. Publication Date Chapter III. Names Section 1. Status Article 6 Section 2. Establishment Article 7. General Requirements Article 8. Registration Chapter IV. Clade Names Article 9. General Requirements for Establishment of Clade Names Article 10. Selection of Clade Names for Establishment Article 11. Specifiers and Qualifying Clauses Chapter V. Selection of Accepted Names Article 12. Precedence Article 13. Homonymy Article 14. Synonymy Article 15. Conservation Chapter VI. Provisions for Hybrids Article 16. Chapter VII. Orthography Article 17. Orthographic Requirements for Establishment Article 18. Subsequent Use and Correction of Established Names Chapter VIII. Authorship of Names Article 19. Chapter IX. Citation of Authors and Registration Numbers Article 20. Chapter X. Governance Article 21. Glossary Table 1. Equivalence of Nomenclatural Terms Appendix A. -

Phylogeny and Avian Evolution Phylogeny and Evolution of the Aves

Phylogeny and Avian Evolution Phylogeny and Evolution of the Aves I. Background Scientists have speculated about evolution of birds ever since Darwin. Difficult to find relatives using only modern animals After publi cati on of “O rigi i in of S peci es” (~1860) some used birds as a counter-argument since th ere were no k nown t ransiti onal f orms at the time! • turtles have modified necks and toothless beaks • bats fly and are warm blooded With fossil discovery other potential relationships! • Birds as distinct order of reptiles Many non-reptilian characteristics (e.g. endothermy, feathers) but really reptilian in structure! If birds only known from fossil record then simply be a distinct order of reptiles. II. Reptile Evolutionary History A. “Stem reptiles” - Cotylosauria Must begin in the late Paleozoic ClCotylosauri a – “il”“stem reptiles” Radiation of reptiles from Cotylosauria can be organized on the basis of temporal fenestrae (openings in back of skull for muscle attachment). Subsequent reptilian lineages developed more powerful jaws. B. Anapsid Cotylosauria and Chelonia have anapsid pattern C. Syypnapsid – single fenestra Includes order Therapsida which gave rise to mammalia D. Diapsida – both supppratemporal and infratemporal fenestrae PttPattern foun did in exti titnct arch osaurs, survi iiving archosaurs and also in primitive lepidosaur – ShSpheno don. All remaining living reptiles and the lineage leading to Aves are classified as Diapsida Handout Mammalia Extinct Groups Cynodontia Therapsida Pelycosaurs Lepidosauromorpha Ichthyosauria Protorothyrididae Synapsida Anapsida Archosauromorpha Euryapsida Mesosaurs Amphibia Sauria Diapsida Eureptilia Sauropsida Amniota Tetrapoda III. Relationshippp to Reptiles Most groups present during Mesozoic considere d ancestors to bird s. -

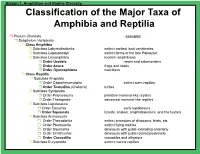

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are -

Osteology of the Dorsal Vertebrae of the Giant Titanosaurian Sauropod Dinosaur Dreadnoughtus Schrani from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works School of Earth & Environment Faculty Scholarship School of Earth & Environment 1-1-2017 Osteology of the dorsal vertebrae of the giant titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur Dreadnoughtus schrani from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina Kristyn Voegele Rowan University Matt Lamanna Kenneth Lacovara Rowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/see_facpub Part of the Anatomy Commons, Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Voegele, K.K., Lamanna, M.C., and Lacovara K.J. (2017). Osteology of the dorsal vertebrae of the giant titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur Dreadnoughtus schrani from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62 (4): 667–681. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Earth & Environment at Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Earth & Environment Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. Editors' choice Osteology of the dorsal vertebrae of the giant titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur Dreadnoughtus schrani from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina KRISTYN K. VOEGELE, MATTHEW C. LAMANNA, and KENNETH J. LACOVARA Voegele, K.K., Lamanna, M.C., and Lacovara K.J. 2017. Osteology of the dorsal vertebrae of the giant titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur Dreadnoughtus schrani from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62 (4): 667–681. Many titanosaurian dinosaurs are known only from fragmentary remains, making comparisons between taxa difficult because they often lack overlapping skeletal elements. This problem is particularly pronounced for the exceptionally large-bodied members of this sauropod clade. Dreadnoughtus schrani is a well-preserved giant titanosaurian from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian–Maastrichtian) Cerro Fortaleza Formation of southern Patagonia, Argentina. -

Anatomy of the Early Cretaceous Enantiornithine Bird Rapaxavis Pani

Anatomy of the Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird Rapaxavis pani JINGMAI K. O’CONNOR, LUIS M. CHIAPPE, CHUNLING GAO, and BO ZHAO O’Connor, J.K., Chiappe, L.M., Gao, C., and Zhao, B. 2011. Anatomy of the Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird Rapaxavis pani. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 56 (3): 463–475. The exquisitely preserved longipterygid enantiornithine Rapaxavis pani is redescribed here after more extensive prepara− tion. A complete review of its morphology is presented based on information gathered before and after preparation. Among other features, Rapaxavis pani is characterized by having an elongate rostrum (close to 60% of the skull length), rostrally restricted dentition, and schizorhinal external nares. Yet, the most puzzling feature of this bird is the presence of a pair of pectoral bones (here termed paracoracoidal ossifications) that, with the exception of the enantiornithine Concornis lacustris, are unknown within Aves. Particularly notable is the presence of a distal tarsal cap, formed by the fu− sion of distal tarsal elements, a feature that is controversial in non−ornithuromorph birds. The holotype and only known specimen of Rapaxavis pani thus reveals important information for better understanding the anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of longipterygids, in particular, as well as basal birds as a whole. Key words: Aves, Enantiornithes, Longipterygidae, Rapaxavis, Jiufotang Formation, Early Cretaceous, China. Jingmai K. O’Connor [[email protected]], Laboratory of Evolutionary Systematics of Vertebrates, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, 142 Xizhimenwaidajie, Beijing, China, 100044; The Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90007 USA; Luis M. Chiappe [[email protected]], The Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Ex− position Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90007 USA; Chunling Gao [[email protected]] and Bo Zhao [[email protected]], Dalian Natural History Museum, No.