1 Excerpted by Permission from Chapter 9 of the Mistaken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript

Page 1 Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript Narrator: For more than a century, Americans have had a love affair with dinosaurs. Extinct for millions of years, they were barely known until giant, fossil bones were discovered in the mid-nineteenth century. Two American scientists, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, led the way to many of these discoveries, at the forefront of the young field of paleontology. Jacques Gauthier, Paleontologist: Every iconic dinosaur every kid grows up with, apatosaurus, triceratops, stegosaurus, allosaurus, these guys went out into the American West and they found that stuff. Narrator: Cope and Marsh shed light on the deep past in a way no one had ever been able to do before. They unearthed more than 130 dinosaur species and some of the first fossil evidence supporting Darwin’s new theory of evolution. Mark Jaffe, Writer: Unfortunately there was a more sordid element, too, which was their insatiable hatred for each other, which often just baffled and exasperated everyone around them. Peter Dodson, Paleontologist: They began life as friends. Then things unraveled… and unraveled in quite a spectacular way. Narrator: Cope and Marsh locked horns for decades, in one of the most bitter scientific rivalries in American history. Constantly vying for leadership in their young field, they competed ruthlessly to secure gigantic bones in the American West. They put American science on the world stage and nearly destroyed one another in the process. Page 2 In the summer of 1868, a small group of scientists boarded a Union Pacific train for a sightseeing excursion through the heart of the newly-opened American West. -

H17 the Descent of Birds < Neornithines, Archaeopteryx

LIFE OF THE MESOZOIC ERA 465 h17 The descent of birds < neornithines, Archaeopteryx, Solnhofen Lms > Alfred, Lord Tennyson / once solved an enigma: When is an / eider [a seaduck] most like a merganser [a lake and river duck]? / He lived long enough to forget the answer. —an anonymous clerihew.1 All eighteen species of penguin live in the Southern Hemisphere. ... The descendants of a common ancestor, sharing common ground. ... ‘This bond, on my [Darwin’s] theory, is simple inheritance.’2 Bird evolution during the Cenozoic has been varied and rapid in the beak but not in the body. For example, Hawaiian Island bird arrivals beginning 5 Ma (million years ago) have evolved to new species with beaks specialized to feed on various flowers and seeds but their bodies have changed so little that the various pioneer-bird stocks are easy to identify. With that perspective, bird varieties distinctive in the beak as owls, hawks, penguins, ducks, flamingos, and parrots, are likely to have diverged in very ancient times. Ducks, albeit primitive ones such as web footed Presbyornis, which could wade but not paddle, already existed in the bird diversity of the Eocene when giant “terror birds,” such as Diatrema, patrolled the ground. Feathers are made mostly of beta keratin, a strong light-weight material. Bird feathers are modified scales which extrude from cells that line skin follicles. The shape and color of the feather so formed can change during the birds growth (say, a downy feather in youth and a stiff feather in adulthood) and by seasonal molts (say, a white feather in the winter and a colored feather for times of courting).3 All birds of the Cenozoic (30 orders) are characterized by toothless jaws and have a pair of elongated foot bones that are partially fused from the bottom up. -

Gerhard Heilmann Og Teorierne Om Fuglenes Oprindelse

Gerhard Heilmann gav DOF et logo længe før ordet var opfundet de Viber, som vi netop med dette nr har forgrebet os på og stiliseret. Ude i verden huskes han imidlertid af en helt anden grund. Gerhard Heilmann og teorierne om fuglenes oprindelse SVEND PALM Archaeopteryx og teorierne I årene 1912 - 1916 bragte DOFT fem artikler, som fik betydning for spørgsmålet om fuglenes oprindelse. Artiklerne var skrevet af Gerhard Heilmann og havde den fælles titel »Vor nuvæ• rende Viden om Fuglenes Afstamning«. Artiklerne tog deres udgangspunkt i et fossil, der i 1861 og 1877 var fundet ved Solnhofen nær Eichstatt, og som fik det videnskabelige navn Archaeopteryx. Dyret var på størrelse med en due, tobenet og havde svingfjer og fjerhale, men det havde også tænder, hvirvelhale og trefingrede forlemmer med klør. Da Archaeopteryx-fundene blev gjort, var der kun gået få årtier, siden man havde fået det første kendskab til de uddøde dinosaurer, af hvilke nog le var tobenede og meget fugleagtige. Her kom da Archaeopteryx, der mest lignede en dinosaur i mini-format, men som med sine fjervinger havde en tydelig tilknytning til fuglene, ind i billedet (Fig. 1). Kort forinden havde Darwin (1859) med sit værk »On the Origin of Species« givet et viden Fig. 1. Archaeopteryx. Fra Heilmann (1926). skabeligt grundlag for udviklingslæren, og Ar chaeopteryx kom meget belejligt som trumfkort for Darwins tilhængere, som et formodet binde led mellem krybdyr og fugle. gernes og flyveevnens opståen. I den nulevende I begyndelsen hæftede man sig især ved lighe fauna findes adskillige eksempler på dyr med en derne mellem dinosaurer, Archaeopteryx og fug vis flyveevne, f.eks. -

Dating Dinosaurs

The PRINCETON FIELD GUIDE to DINOSAURS 2ND EDITION PRINCETON FIELD GUIDES Rooted in field experience and scientific study, Princeton’s guides to animals and plants are the authority for professional scientists and amateur naturalists alike. Princeton Field Guides present this information in a compact format carefully designed for easy use in the field. The guides illustrate every species in color and provide detailed information on identification, distribution, and biology. Albatrosses, Petrels, and Shearwaters of the World, by Derek Onley Birds of Southern Africa, Fourth Edition, by Ian Sinclair, Phil and Paul Scofield Hockey, Warwick Tarboton, and Peter Ryan Birds of Aruba, Curaçao, and Bonaire by Bart de Boer, Eric Birds of Thailand, by Craig Robson Newton, and Robin Restall Birds of the West Indies, by Herbert Raffaele, James Wiley, Birds of Australia, Eighth Edition, by Ken Simpson and Nicolas Orlando Garrido, Allan Keith, and Janis Raffaele Day Birds of Western Africa, by Nik Borrow and Ron Demey Birds of Borneo: Brunei, Sabah, Sarawak, and Kalimantan, by Carnivores of the World, by Luke Hunter Susan Myers Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification Birds of Botswana, by Peter Hancock and Ingrid Weiersbye and Natural History, by David L. Wagner Birds of Central Asia, by Raffael Ayé, Manuel Schweizer, and Common Mosses of the Northeast and Appalachians, by Karl B. Tobias Roth McKnight, Joseph Rohrer, Kirsten McKnight Ward, and Birds of Chile, by Alvaro Jaramillo Warren Perdrizet Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti, by Steven Latta, Coral Reef Fishes, by Ewald Lieske and Robert Meyers Christopher Rimmer, Allan Keith, James Wiley, Herbert Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East, by Dennis Paulson Raffaele, Kent McFarland, and Eladio Fernandez Dragonflies and Damselflies of the West, by Dennis Paulson Birds of East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and Mammals of Europe, by David W. -

Tiago Rodrigues Simões

Diapsid Phylogeny and the Origin and Early Evolution of Squamates by Tiago Rodrigues Simões A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in SYSTEMATICS AND EVOLUTION Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta © Tiago Rodrigues Simões, 2018 ABSTRACT Squamate reptiles comprise over 10,000 living species and hundreds of fossil species of lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians, with their origins dating back at least as far back as the Middle Jurassic. Despite this enormous diversity and a long evolutionary history, numerous fundamental questions remain to be answered regarding the early evolution and origin of this major clade of tetrapods. Such long-standing issues include identifying the oldest fossil squamate, when exactly did squamates originate, and why morphological and molecular analyses of squamate evolution have strong disagreements on fundamental aspects of the squamate tree of life. Additionally, despite much debate, there is no existing consensus over the composition of the Lepidosauromorpha (the clade that includes squamates and their sister taxon, the Rhynchocephalia), making the squamate origin problem part of a broader and more complex reptile phylogeny issue. In this thesis, I provide a series of taxonomic, phylogenetic, biogeographic and morpho-functional contributions to shed light on these problems. I describe a new taxon that overwhelms previous hypothesis of iguanian biogeography and evolution in Gondwana (Gueragama sulamericana). I re-describe and assess the functional morphology of some of the oldest known articulated lizards in the world (Eichstaettisaurus schroederi and Ardeosaurus digitatellus), providing clues to the ancestry of geckoes, and the early evolution of their scansorial behaviour. -

Archaeopteryx Feathers and Bone Chemistry Fully Revealed Via Synchrotron Imaging

Archaeopteryx feathers and bone chemistry fully revealed via synchrotron imaging U. Bergmanna, R. W. Mortonb, P. L. Manningc,d, W. I. Sellerse, S. Farrarf, K. G. Huntleyb, R. A. Wogeliusc,g,1, and P. Larsonc,f aStanford Linear Accelerator Center National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, Menlo Park, CA 94025; bChildren of the Middle Waters Institute, Bartlesville, OK, 74003; cSchool of Earth, Atmospheric, and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PL, United Kingdom; dDepartment of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, 19104; eFaculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PT, United Kingdom; fBlack Hills Institute of Geological Research, Inc., Hill City, SD, 57745; and gWilliamson Research Centre for Molecular Environmental Science, University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PL, United Kingdom Communicated by Philip H. Bucksbaum, Stanford University, Menlo Park, CA, February 16, 2010 (received for review August 12, 2009) Evolution of flight in maniraptoran dinosaurs is marked by the ac- with the contextual information SRS-XRF provides about the se- quisition of distinct avian characters, such as feathers, as seen in dimentary matrix, can be used to help explain how this detailed Archaeopteryx from the Solnhofen limestone. These rare fossils fossil has survived over 150 million years. SRS-XRF thus allows were pivotal in confirming the dinosauria-avian lineage. One of direct study of (i) structures that are not apparent in visible light, the key derived avian characters is the possession of feathers, de- (ii) macronutrient and trace metal distribution patterns in bone tails of which were remarkably preserved in the Lagerstätte envi- and mineralized soft tissue areas related to life processes, and (iii) ronment. -

Insight Into the Evolution of Avian Flight from a New Clade of Early

J. Anat. (2006) 208, pp287–308 IBlackwnell Publishing sLtd ight into the evolution of avian flight from a new clade of Early Cretaceous ornithurines from China and the morphology of Yixianornis grabaui Julia A. Clarke,1 Zhonghe Zhou2 and Fucheng Zhang2 1Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Abstract In studies of the evolution of avian flight there has been a singular preoccupation with unravelling its origin. By con- trast, the complex changes in morphology that occurred between the earliest form of avian flapping flight and the emergence of the flight capabilities of extant birds remain comparatively little explored. Any such work has been limited by a comparative paucity of fossils illuminating bird evolution near the origin of the clade of extant (i.e. ‘modern’) birds (Aves). Here we recognize three species from the Early Cretaceous of China as comprising a new lineage of basal ornithurine birds. Ornithurae is a clade that includes, approximately, comparatively close relatives of crown clade Aves (extant birds) and that crown clade. The morphology of the best-preserved specimen from this newly recognized Asian diversity, the holotype specimen of Yixianornis grabaui Zhou and Zhang 2001, complete with finely preserved wing and tail feather impressions, is used to illustrate the new insights offered by recognition of this lineage. Hypotheses of avian morphological evolution and specifically proposed patterns of change in different avian locomotor modules after the origin of flight are impacted by recognition of the new lineage. -

Phylocode: a Phylogenetic Code of Biological Nomenclature

PhyloCode: A Phylogenetic Code of Biological Nomenclature Philip D. Cantino and Kevin de Queiroz (equal contributors; names listed alphabetically) Advisory Group: William S. Alverson, David A. Baum, Harold N. Bryant, David C. Cannatella, Peter R. Crane, Michael J. Donoghue, Torsten Eriksson*, Jacques Gauthier, Kenneth Halanych, David S. Hibbett, David M. Hillis, Kathleen A. Kron, Michael S. Y. Lee, Alessandro Minelli, Richard G. Olmstead, Fredrik Pleijel*, J. Mark Porter, Heidi E. Robeck, Greg W. Rouse, Timothy Rowe*, Christoffer Schander, Per Sundberg, Mikael Thollesson, and Andre R. Wyss. *Chaired a committee that authored a portion of the current draft. Most recent revision: April 8, 2000 1 Table of Contents Preface Preamble Division I. Principles Division II. Rules Chapter I. Taxa Article 1. The Nature of Taxa Article 2. Clades Article 3. Hierarchy and Rank Chapter II. Publication Article 4. Publication Requirements Article 5. Publication Date Chapter III. Names Section 1. Status Article 6 Section 2. Establishment Article 7. General Requirements Article 8. Registration Chapter IV. Clade Names Article 9. General Requirements for Establishment of Clade Names Article 10. Selection of Clade Names for Establishment Article 11. Specifiers and Qualifying Clauses Chapter V. Selection of Accepted Names Article 12. Precedence Article 13. Homonymy Article 14. Synonymy Article 15. Conservation Chapter VI. Provisions for Hybrids Article 16. Chapter VII. Orthography Article 17. Orthographic Requirements for Establishment Article 18. Subsequent Use and Correction of Established Names Chapter VIII. Authorship of Names Article 19. Chapter IX. Citation of Authors and Registration Numbers Article 20. Chapter X. Governance Article 21. Glossary Table 1. Equivalence of Nomenclatural Terms Appendix A. -

Alan Feduccia's Riddle of the Feathered Dragons: What Reptiles

Leigh Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:9 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/9 BOOK REVIEW Open Access Alan Feduccia’s Riddle of the Feathered Dragons: what reptiles gave rise to birds? Egbert Giles Leigh Jr Riddle of the Feathered Dragons: Hidden Birds of China, properly. This is a great pity, for his story is wonderful: by Alan Feduccia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, his birds would have made a far better focus for this 2012. Pp. x + 358. H/b $55.00 book than the dispute. This book’s author is at home in the paleontology, So, what is this dispute that spoiled the book? The anatomy, physiology, and behavior of birds. Who could scientific argument is easily summarized. It started be more qualified to write on their origin and evolution? when a paleontologist from Yale University, John Ostrom, This book is unusually, indeed wonderfully, well and unearthed a 75-kg bipedal theropod dinosaur, Deinonychus, clearly illustrated: its producers cannot be praised too buried 110 million years ago in Montana. Deinonychus highly. It is well worth the while of anyone interested in stood a meter tall, and its tail was 1.5 m long. It was active: bird evolution to read it. Although it offers no answers Ostrom thought that both it and Archaeopteryx,which to ‘where birds came from’, it has God’s plenty of fascin- lived 40 million years earlier, were warm-blooded. Deinony- ating, revealing detail, knit together in powerful criticism chus bore many skeletal resemblances to Archaeopteryx, of prevailing views of bird evolution. -

Phylogeny and Avian Evolution Phylogeny and Evolution of the Aves

Phylogeny and Avian Evolution Phylogeny and Evolution of the Aves I. Background Scientists have speculated about evolution of birds ever since Darwin. Difficult to find relatives using only modern animals After publi cati on of “O rigi i in of S peci es” (~1860) some used birds as a counter-argument since th ere were no k nown t ransiti onal f orms at the time! • turtles have modified necks and toothless beaks • bats fly and are warm blooded With fossil discovery other potential relationships! • Birds as distinct order of reptiles Many non-reptilian characteristics (e.g. endothermy, feathers) but really reptilian in structure! If birds only known from fossil record then simply be a distinct order of reptiles. II. Reptile Evolutionary History A. “Stem reptiles” - Cotylosauria Must begin in the late Paleozoic ClCotylosauri a – “il”“stem reptiles” Radiation of reptiles from Cotylosauria can be organized on the basis of temporal fenestrae (openings in back of skull for muscle attachment). Subsequent reptilian lineages developed more powerful jaws. B. Anapsid Cotylosauria and Chelonia have anapsid pattern C. Syypnapsid – single fenestra Includes order Therapsida which gave rise to mammalia D. Diapsida – both supppratemporal and infratemporal fenestrae PttPattern foun did in exti titnct arch osaurs, survi iiving archosaurs and also in primitive lepidosaur – ShSpheno don. All remaining living reptiles and the lineage leading to Aves are classified as Diapsida Handout Mammalia Extinct Groups Cynodontia Therapsida Pelycosaurs Lepidosauromorpha Ichthyosauria Protorothyrididae Synapsida Anapsida Archosauromorpha Euryapsida Mesosaurs Amphibia Sauria Diapsida Eureptilia Sauropsida Amniota Tetrapoda III. Relationshippp to Reptiles Most groups present during Mesozoic considere d ancestors to bird s. -

Dinosaur Art Evolves with New Discoveries in Paleontology Amy Mcdermott, Science Writer

SCIENCE AND CULTURE SCIENCE AND CULTURE Dinosaur art evolves with new discoveries in paleontology Amy McDermott, Science Writer Under soft museum lights, the massive skeleton of a Those creations necessarily require some artistic Tyrannosaurus rex is easy to imagine fleshed out and license, says freelancer Gabriel Ugueto, who’s based alive, scimitar teeth glimmering. What did it look like in Miami, FL. As new discoveries offer artists a better in life? How did its face contort under the Montana sun sense of what their subjects looked like, the findings some 66 million years ago? What color and texture also constrain their creativity, he says, by leaving fewer was its body? Was it gauntly wrapped in scales, fluffy details to the imagination. with feathers, or a mix of both? Even so, he and other artists welcome new discov- Increasingly, paleontologists can offer answers to eries, as the field strives for accuracy. The challenge these questions, thanks to evidence of dinosaur soft now is sifting through all this new information, including tissues discovered in the last 30 years. Translating those characteristics that are still up for debate, such as the discoveries into works that satisfy the public’simagination extent of T. rex’s feathers, to conjure new visions of the is the purview of paleoartists, the scientific illustrators prehistoric world. who reconstruct prehistory in paintings, drawings, and Paleoartists often have a general science back- sculptures in exhibit halls, books, magazines, and films. ground or formal artistic training, although career Among the earliest examples of paleoart, this 1830 watercolor painting, called Duria Antiquior or “A more ancient Dorset,” imagines England’s South Coast populated by ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaurs. -

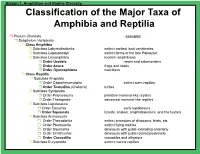

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are