Dinosaur Art Evolves with New Discoveries in Paleontology Amy Mcdermott, Science Writer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSMS General Assembly Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Annual

Colorado Springs Mineralogical Society Founded in 1936 Lazard Cahn Honorary President December 2018 PICK&PACK Vol 58 .. Number #10 Inside this Issue: CSMS General Assembly CSMS Calendar Pg. 2 Kansas Pseudo- Morphs: Pg. 4 Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Limonite After Pyrite Duria Antiquior: A Annual Christmas Party 19th Century Fore- Pg. 7 runner of Paleoart CSMS Rockhounds of Pg. 9 the Year & 10 Pebble Pups Pg10 **In case of inclement weather, please call** Secretary’s Spot Pg11 Mt. Carmel Veteran’s Service Center 719 309-4714 Classifieds Pg17 Annual Christmas Party Details Please mark your calendars and plan to attend the annual Christmas Party at the Mt. Carmel Veteran's Service Center.on Thursday, December 20, at 7PM. We will provide roast turkey and baked ham as well as Bill Arnson's chili. Members whose last names begin with A--P, please bring a side dish to share. Those whose last names begin with Q -- Z, please bring a dessert to share. There will be a gift exchange for those who want to participate. Please bring a wrapped hobby-related gift valued at $10.00 or less to exchange. We will have a short business meeting to vote on some bylaw changes, and to elect next year's Board of Directors. The Board candidates are as follows: President: Sharon Holte Editor: Taylor Harper Vice President: John Massie Secretary: ?????? Treasurer: Ann Proctor Member-at-Large: Laurann Briding Membership Secretary: Adelaide Barr Member-at Large: Bill Arnson Past president: Ernie Hanlon We are in desperate need of a secretary to serve on the Board. -

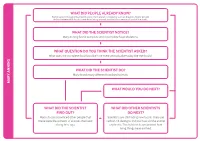

What Did the Scientist Notice? What Question Do You Think

WHAT DID PEOPLE ALREADY KNOW? Some people thought that fossils came from ancient creatures such as dragons. Some people did not believe that fossils came from living animals or plants but were just part of the rocks. WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST NOTICE? Mary Anning found complete and incomplete fossil skeletons. WHAT QUESTION DO YOU THINK THE SCIENTIST ASKED? What does the complete fossil look like? Are there animals alive today like the fossils? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST DO? Mary found many different fossilised animals. MARY ANNING MARY WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST WHAT DID OTHER SCIENTISTS FIND OUT? DO NEXT? Mary’s fossils convinced other people that Scientists are still finding new fossils. They use these were the remains of animals that lived carbon-14 dating to find out how old the animal a long time ago. or plant is. This helps us to understand how living things have evolved. s 1823 / 1824 1947 Mary Anning (1823) discovered a nearly complete plesiosaur Carbon-14 dating enables scientists to determine the age of a formerly skeleton at Lyme Regis. living thing more accurately. When a Tail fossils of a baby species William Conybeare (1824) living organism dies, it stops taking in of Coelurosaur, fully People often found fossils on the beach described Mary’s plesiosaur to the new carbon. Measuring the amount preserved in amber including and did not know what they were, so Geographical Society. They debated of 14C in a fossil sample provides soft tissue, were found in 2016 BEFORE 1800 BEFORE gave them interesting names such as whether it was a fake, but Mary was information that can be used to Myanmar. -

Offer Your Guests a Visually Stunning and Interactive Experience They Won’T Find Anywhere Else World of Animals

Creative Arts & Attractions Offer Your Guests a Visually Stunning and Interactive Experience They Won’t Find Anywhere Else World of Animals Entertain guests with giant illuminated, eye-catching displays of animals from around the world. Animal displays are made in the ancient Eastern tradition of lantern-making with 3-D metal frames, fiberglass, and acrylic materials. Unique and captivating displays will provide families and friends with a lifetime of memories. Animatronic Dinosaurs Fascinate patrons with an impressive visual spectacle in our exhibitions. Featured with lifelike appearances, vivid movements and roaring sounds. From the very small to the gigantic dinosaurs, we have them all. Everything needed for a realistic and immersive experience for your patrons. Providing interactive options for your event including riding dinosaurs and dinosaur inflatable slides. Enhancing your merchandise stores with dinosaur balloons and toys. Animatronic Dinosaur Options Abelisaurus Maiasaura Acrocanthosaurus Megalosaurus Agilisaurus Olorotitan arharensis Albertosaurus Ornithomimus Allosaurus Ouranosaurus nigeriensis Ankylosaurus Oviraptor philoceratops Apatosaurus Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis Archaeopteryx Parasaurolophus Baryonyx Plateosaurus Brachiosaurus Protoceratops andrewsi Carcharodontosaurus Pterosauria Carnotaurus Pteranodon longiceps Ceratosaurus Raptorex Coelophysis Rugops Compsognathus Spinosaurus Deinonychus Staurikosaurus pricei Dilophosaurus Stegoceras Diplodocus Stegosaurus Edmontosaurus Styracosaurus Eoraptor Lunensis Suchomimus -

Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) Was One of the First Fossil Collectors

Geology Section: history, interests and the importance of Devon‟s geology Malcolm Hart [Vice-Chair Geology Section] School of Geography, Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Plymouth Devonshire Association, Forum, Sidmouth, March 2020 Slides: 3 – 13 South-West England people; 14 – 25 Our northward migration; 24 – 33 Climate change: a modern problem; 34 – 50 Our geoscience heritage: Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site and the English Riviera UNESCO Global Geopark; 51 – 53 Summary and perspectives When we look at the natural landscape it can appear almost un- changing – even in the course of a life- time. William Smith (1769–1839) was a practical engineer, who used geology in an applied way. He recognised that the fossils he found could indicate the „stratigraphy‟ of the rocks that his work encountered. His map was produced in 1815. Images © Geological Society of London Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) was one of the first fossil collectors. At the time the area was being quarried, though features such as the „ammonite pavement‟ were left for science. Image © Geological Society of London Images © National Museum, Wales Sir Henry De La Beche (1796‒1855) was an extraordinary individual. He wrote on the geology of Devon, Cornwall and Somerset, while living in Lyme Regis. He studied the local geology and created, in Duria Antiquior (a more ancient Dorset) the first palaeoecological reconstruction. He was often ridiculed for this! He was also the first Director of the British Geological Survey. His suggestion, in 1839, that the rocks of Devonshire and Cornwall were „distinctive‟ led to the creation of the Devonian System in 1840. -

The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Second Edition

MASS ESTIMATES - DINOSAURS ETC (largely based on models) taxon k model femur length* model volume ml x specific gravity = model mass g specimen (modeled 1st):kilograms:femur(or other long bone length)usually in decameters kg = femur(or other long bone)length(usually in decameters)3 x k k = model volume in ml x specific gravity(usually for whole model) then divided/model femur(or other long bone)length3 (in most models femur in decameters is 0.5253 = 0.145) In sauropods the neck is assigned a distinct specific gravity; in dinosaurs with large feathers their mass is added separately; in dinosaurs with flight ablity the mass of the fight muscles is calculated separately as a range of possiblities SAUROPODS k femur trunk neck tail total neck x 0.6 rest x0.9 & legs & head super titanosaur femur:~55000-60000:~25:00 Argentinosaurus ~4 PVPH-1:~55000:~24.00 Futalognkosaurus ~3.5-4 MUCPv-323:~25000:19.80 (note:downsize correction since 2nd edition) Dreadnoughtus ~3.8 “ ~520 ~75 50 ~645 0.45+.513=.558 MPM-PV 1156:~26000:19.10 Giraffatitan 3.45 .525 480 75 25 580 .045+.455=.500 HMN MB.R.2181:31500(neck 2800):~20.90 “XV2”:~45000:~23.50 Brachiosaurus ~4.15 " ~590 ~75 ~25 ~700 " +.554=~.600 FMNH P25107:~35000:20.30 Europasaurus ~3.2 “ ~465 ~39 ~23 ~527 .023+.440=~.463 composite:~760:~6.20 Camarasaurus 4.0 " 542 51 55 648 .041+.537=.578 CMNH 11393:14200(neck 1000):15.25 AMNH 5761:~23000:18.00 juv 3.5 " 486 40 55 581 .024+.487=.511 CMNH 11338:640:5.67 Chuanjiesaurus ~4.1 “ ~550 ~105 ~38 ~693 .063+.530=.593 Lfch 1001:~10700:13.75 2 M. -

Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19Th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology

Headwaters Volume 26 Article 14 2009 Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters Part of the Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2009) "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology," Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Headwaters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LARRY E. DAVIS Mary Anning of Lyme Regis 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Ludwig Leichhardt, a 19th century German explorer noted in a letter, “… we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of Palaeontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression …” (Aurousseau, 1968). Gideon Mantell, a 19th century British palaeontologist, made a less flattering remark when he wrote in his journal, “… sallied out in quest of Mary An- ning, the geological lioness … we found her in a little dirt shop with hundreds of specimens piled around her in the greatest disorder. She, the presiding Deity, a prim, pedantic vinegar looking female; shred, and rather satirical in her conversation” (Curwin, 1940). Who was Mary Anning, this Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness (Fig. -

Teacher's Booklet

Ideas and Evidence at the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Teacher’s Booklet Acknowledgements Shawn Peart Secondary Consultant Annette Shelford Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Paul Dainty Great Cornard Upper School Sarah Taylor St. James Middle School David Heap Westley Middle School Thanks also to Dudley Simons for photography and processing of the images of objects and exhibits at the Sedgwick Museum, and to Adrienne Mayor for kindly allowing us to use her mammoth and monster images (see picture credits). Picture Credits Page 8 “Bag of bones” activity adapted from an old resource, source unknown. Page 8 Iguanodon images used in the interpretation of the skeleton picture resource from www.dinohunters.com Page 9 Mammoth skeleton images from ‘The First Fossil Hunters’ by Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press ISBN: 0-691-05863 with kind permission of the author Page 9 Both paintings of Mary Anning from the collections of the Natural History Museum © Natural History Museum, London 1 Page 12 Palaeontologists Picture from the photographic archive of the Sedgwick Museum © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 14 Images of Iguanodon from www.dinohunters.com Page 15 “Duria Antiquior - a more ancient Dorsetshire” by Henry de la Beche from the collection of the National Museums and Galleries of Wales © National Museum of Wales Page 17 Images of Deinotherium giganteum skull cast © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 19 Image of red sandstone slab © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences 2 Introduction Ideas and evidence was introduced as an aspect of school science after the review of the National Curriculum in 2000. Until the advent of the National Strategy for Science it was an area that was often not planned for explicitly. -

State of the Palaeoart

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org State of the Palaeoart Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway The discipline of palaeoart, a branch of natural history art dedicated to the recon- struction of extinct life, is an established and important component of palaeontological science and outreach. For more than 200 years, palaeoartistry has worked closely with palaeontological science and has always been integral to the enduring popularity of prehistoric animals with the public. Indeed, the perceived value or success of such products as popular books, movies, documentaries, and museum installations can often be linked to the quality and panache of its palaeoart more than anything else. For all its significance, the palaeoart industry ment part of this dialogue in the published is often poorly treated by the academic, media and literature, in turn bringing the issues concerned to educational industries associated with it. Many wider attention. We argue that palaeoartistry is standard practises associated with palaeoart pro- both scientifically and culturally significant, and that duction are ethically and legally problematic, stifle improved working practises are required by those its scientific and cultural growth, and have a nega- involved in its production. We hope that our views tive impact on the financial viability of its creators. inspire discussion and changes sorely needed to These issues create a climate that obscures the improve the economy, quality and reputation of the many positive contributions made by palaeoartists palaeoart industry and its contributors. to science and education, while promoting and The historic, scientific and economic funding derivative, inaccurate, and sometimes exe- significance of palaeoart crable artwork. -

Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in Later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2020-0174.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Holtz, Thomas; University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Geology; NationalDraft Museum of Natural History, Department of Geology Keyword: Dinosaur, Ontogeny, Theropod, Paleocology, Mesozoic, Tyrannosauridae Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Tribute to Dale Russell Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 91 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: 2 Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous 3 Asiamerica 4 5 6 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 7 8 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA 9 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013 USA 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ORCID: 0000-0002-2906-4900 Draft 12 13 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 14 Department of Geology 15 8000 Regents Drive 16 University of Maryland 17 College Park, MD 20742 18 USA 19 Phone: 1-301-405-4084 20 Fax: 1-301-314-9661 21 Email address: [email protected] 22 23 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 91 24 ABSTRACT 25 Well-sampled dinosaur communities from the Jurassic through the early Late Cretaceous show 26 greater taxonomic diversity among larger (>50kg) theropod taxa than communities of the 27 Campano-Maastrichtian, particularly to those of eastern/central Asia and Laramidia. -

An Investigation Into the Graphic Innovations of Geologist Henry T

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche Renee M. Clary Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Clary, Renee M., "Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 127. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/127 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. UNCOVERING STRATA: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE GRAPHIC INNOVATIONS OF GEOLOGIST HENRY T. DE LA BECHE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Renee M. Clary B.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1983 M.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1997 M.Ed., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Renee M. Clary All rights reserved ii Acknowledgments Photographs of the archived documents held in the National Museum of Wales are provided by the museum, and are reproduced with permission. I send a sincere thank you to Mr. Tom Sharpe, Curator, who offered his time and assistance during the research trip to Wales. -

Visions of the Prehistoric Past Reviewed by Mark P. Witton

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past Reviewed by Mark P. Witton Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past. 2017. Written by Zoë Lescaze and Walton Ford. Taschen. 292 pages, ISBN 978-3-8365-5511-1 (English edition). € 75, £75, $100 (hardcover) Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past is a collection of palaeoartworks spanning 150 years of palaeoart history, from 1830 to the second half of the 20th century. This huge, supremely well-pre- sented book was primarily written by journalist, archaeological illustrator and art scholar Zoë Les- caze, with an introduction by artist Walton Ford (both are American, and use ‘paleoart’ over the European spelling ‘palaeoart’). Ford states that the genesis of the book reflects “the need for a paleo- art book that was more about the art and less about the paleo” (p. 12), and thus Paleoart skews towards artistic aspects of palaeoartistry rather than palaeontological theory or technical aspects of reconstructing extinct animal appearance. Ford and Lescaze are correct that this angle of palaeo- artistry remains neglected, and this puts Paleoart in prime position to make a big impact on this pop- ular, though undeniably niche subject. Paleoart is extremely well-produced and stun- ning to look at, a visual feast for anyone with an interest in classic palaeoart. 292 pages of thick, sturdy paper (9 chapters, hundreds of images, and four fold outs) and almost impractical dimensions (28 x 37.4 cm) make it a physically imposing, stately tome that reminds us why books belong on shelves and not digital devices. Focusing exclu- sively on 2D art, the layout is minimalist and clean, detail, unobscured by text and labelling. -

Tiago Rodrigues Simões

Diapsid Phylogeny and the Origin and Early Evolution of Squamates by Tiago Rodrigues Simões A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in SYSTEMATICS AND EVOLUTION Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta © Tiago Rodrigues Simões, 2018 ABSTRACT Squamate reptiles comprise over 10,000 living species and hundreds of fossil species of lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians, with their origins dating back at least as far back as the Middle Jurassic. Despite this enormous diversity and a long evolutionary history, numerous fundamental questions remain to be answered regarding the early evolution and origin of this major clade of tetrapods. Such long-standing issues include identifying the oldest fossil squamate, when exactly did squamates originate, and why morphological and molecular analyses of squamate evolution have strong disagreements on fundamental aspects of the squamate tree of life. Additionally, despite much debate, there is no existing consensus over the composition of the Lepidosauromorpha (the clade that includes squamates and their sister taxon, the Rhynchocephalia), making the squamate origin problem part of a broader and more complex reptile phylogeny issue. In this thesis, I provide a series of taxonomic, phylogenetic, biogeographic and morpho-functional contributions to shed light on these problems. I describe a new taxon that overwhelms previous hypothesis of iguanian biogeography and evolution in Gondwana (Gueragama sulamericana). I re-describe and assess the functional morphology of some of the oldest known articulated lizards in the world (Eichstaettisaurus schroederi and Ardeosaurus digitatellus), providing clues to the ancestry of geckoes, and the early evolution of their scansorial behaviour.