Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) Was One of the First Fossil Collectors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSMS General Assembly Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Annual

Colorado Springs Mineralogical Society Founded in 1936 Lazard Cahn Honorary President December 2018 PICK&PACK Vol 58 .. Number #10 Inside this Issue: CSMS General Assembly CSMS Calendar Pg. 2 Kansas Pseudo- Morphs: Pg. 4 Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Limonite After Pyrite Duria Antiquior: A Annual Christmas Party 19th Century Fore- Pg. 7 runner of Paleoart CSMS Rockhounds of Pg. 9 the Year & 10 Pebble Pups Pg10 **In case of inclement weather, please call** Secretary’s Spot Pg11 Mt. Carmel Veteran’s Service Center 719 309-4714 Classifieds Pg17 Annual Christmas Party Details Please mark your calendars and plan to attend the annual Christmas Party at the Mt. Carmel Veteran's Service Center.on Thursday, December 20, at 7PM. We will provide roast turkey and baked ham as well as Bill Arnson's chili. Members whose last names begin with A--P, please bring a side dish to share. Those whose last names begin with Q -- Z, please bring a dessert to share. There will be a gift exchange for those who want to participate. Please bring a wrapped hobby-related gift valued at $10.00 or less to exchange. We will have a short business meeting to vote on some bylaw changes, and to elect next year's Board of Directors. The Board candidates are as follows: President: Sharon Holte Editor: Taylor Harper Vice President: John Massie Secretary: ?????? Treasurer: Ann Proctor Member-at-Large: Laurann Briding Membership Secretary: Adelaide Barr Member-at Large: Bill Arnson Past president: Ernie Hanlon We are in desperate need of a secretary to serve on the Board. -

What Did the Scientist Notice? What Question Do You Think

WHAT DID PEOPLE ALREADY KNOW? Some people thought that fossils came from ancient creatures such as dragons. Some people did not believe that fossils came from living animals or plants but were just part of the rocks. WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST NOTICE? Mary Anning found complete and incomplete fossil skeletons. WHAT QUESTION DO YOU THINK THE SCIENTIST ASKED? What does the complete fossil look like? Are there animals alive today like the fossils? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST DO? Mary found many different fossilised animals. MARY ANNING MARY WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST WHAT DID OTHER SCIENTISTS FIND OUT? DO NEXT? Mary’s fossils convinced other people that Scientists are still finding new fossils. They use these were the remains of animals that lived carbon-14 dating to find out how old the animal a long time ago. or plant is. This helps us to understand how living things have evolved. s 1823 / 1824 1947 Mary Anning (1823) discovered a nearly complete plesiosaur Carbon-14 dating enables scientists to determine the age of a formerly skeleton at Lyme Regis. living thing more accurately. When a Tail fossils of a baby species William Conybeare (1824) living organism dies, it stops taking in of Coelurosaur, fully People often found fossils on the beach described Mary’s plesiosaur to the new carbon. Measuring the amount preserved in amber including and did not know what they were, so Geographical Society. They debated of 14C in a fossil sample provides soft tissue, were found in 2016 BEFORE 1800 BEFORE gave them interesting names such as whether it was a fake, but Mary was information that can be used to Myanmar. -

Draft Charmouth Neighbourhood Plan

Charmouth Parish Draft Neighbourhood Plan 2021 – 2035 May 2021 Submission Draft Prepared by the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group on behalf of Charmouth Parish Council Executive Summary What this Plan does… This Neighbourhood Plan sets out planning policies for Charmouth Parish. It will be used by Dorset Council when making decisions on planning applications. It doesn’t cover every issue that could occur as a planning consideration, but it does strengthen the approach taken in the Local Plan by providing more detail of specific issues in some key areas that will make the planning system work better for Charmouth. This Plan reflects the responses received from consultation which we have used to develop and shape the policies. We thought it would be useful to summarise, very briefly, what some of the main policies are and where we expect our Neighbourhood Plan to make a real difference… VISION AND OBJECTIVES The Vision and Objectives for the Plan, on which the policies have been developed, include the development of small scale housing; protecting the village’s unique characteristics; supporting local businesses and amenities; continuing to attract tourists and visitors and enhancing, where possible, the quality of life for residents. In short, the Plan reflects a balance between encouraging moderate growth and development whilst protecting the uniqueness of our village and its natural environment. See Table 2.1 for more information We have also identified a range of Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats. See Table 2.2 for more information HERITAGE AND HISTORY The Parish has many historical buildings many of which are Listed, and there is a sizeable Conservation Area. -

Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19Th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology

Headwaters Volume 26 Article 14 2009 Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters Part of the Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2009) "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology," Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Headwaters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LARRY E. DAVIS Mary Anning of Lyme Regis 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Ludwig Leichhardt, a 19th century German explorer noted in a letter, “… we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of Palaeontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression …” (Aurousseau, 1968). Gideon Mantell, a 19th century British palaeontologist, made a less flattering remark when he wrote in his journal, “… sallied out in quest of Mary An- ning, the geological lioness … we found her in a little dirt shop with hundreds of specimens piled around her in the greatest disorder. She, the presiding Deity, a prim, pedantic vinegar looking female; shred, and rather satirical in her conversation” (Curwin, 1940). Who was Mary Anning, this Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness (Fig. -

Teacher's Booklet

Ideas and Evidence at the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Teacher’s Booklet Acknowledgements Shawn Peart Secondary Consultant Annette Shelford Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Paul Dainty Great Cornard Upper School Sarah Taylor St. James Middle School David Heap Westley Middle School Thanks also to Dudley Simons for photography and processing of the images of objects and exhibits at the Sedgwick Museum, and to Adrienne Mayor for kindly allowing us to use her mammoth and monster images (see picture credits). Picture Credits Page 8 “Bag of bones” activity adapted from an old resource, source unknown. Page 8 Iguanodon images used in the interpretation of the skeleton picture resource from www.dinohunters.com Page 9 Mammoth skeleton images from ‘The First Fossil Hunters’ by Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press ISBN: 0-691-05863 with kind permission of the author Page 9 Both paintings of Mary Anning from the collections of the Natural History Museum © Natural History Museum, London 1 Page 12 Palaeontologists Picture from the photographic archive of the Sedgwick Museum © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 14 Images of Iguanodon from www.dinohunters.com Page 15 “Duria Antiquior - a more ancient Dorsetshire” by Henry de la Beche from the collection of the National Museums and Galleries of Wales © National Museum of Wales Page 17 Images of Deinotherium giganteum skull cast © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 19 Image of red sandstone slab © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences 2 Introduction Ideas and evidence was introduced as an aspect of school science after the review of the National Curriculum in 2000. Until the advent of the National Strategy for Science it was an area that was often not planned for explicitly. -

An Investigation Into the Graphic Innovations of Geologist Henry T

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche Renee M. Clary Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Clary, Renee M., "Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 127. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/127 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. UNCOVERING STRATA: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE GRAPHIC INNOVATIONS OF GEOLOGIST HENRY T. DE LA BECHE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Renee M. Clary B.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1983 M.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1997 M.Ed., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Renee M. Clary All rights reserved ii Acknowledgments Photographs of the archived documents held in the National Museum of Wales are provided by the museum, and are reproduced with permission. I send a sincere thank you to Mr. Tom Sharpe, Curator, who offered his time and assistance during the research trip to Wales. -

January, 2019

Lake George Gem & Mineral Club January, 2019 Program for the Month: Saturday, January 12, 2019, 10:00 a.m. Dinosaur Tracks presented by Paul Combs For a long time, people looked at dinosaur tracks as nothing more than "curiosities". Even paleontologists used them as door stops and paper weights, or gave them away to friends. No more. About 30 years ago, the study of dinosaur tracks really took off, and the discoveries are nothing short of amazing. In that short time, we have discovered a lot about how fast different dinosaurs walked or ran, how they stood, what they ate, how they hunted, that they swam, how they courted their mates, how they raised their young, that they traveled in herds, and much more. And more track sites are being discovered in the USA and around the world every year. Paul Combs will explain the techniques that scientists are using and what all this work is teaching us. For instance, Steven Spielberg used this new information in the making of the "Jurassic Park" series of films. Some of these discoveries are happening right now, at sites here in Colorado! Silent Auction: We need donations for the silent auction! If you have “extras”, whether minerals, fossils, books, or other items, and if you have a label saying what the item is and where it came from, we can use it. If not, bring some cash and be prepared to help support Club activities, including scholarships, Pebble Pups, and other items. From the President-elect -- Richard Kawamoto: A Happy New Year wish and a hearty welcome to another exciting year of activities with the Lake George Gem & Mineral Club. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Cover sheet 2 1 Policy Details 2 2 Status and Approvals 3 Jurassic Coast Partnership Plan 2020 - 2025 4 Equality Impact Assessment 48 Jurassic Coast Partnership Plan 2020 - 2025 Policy Details What is this policy The Jurassic Coast partnership Plan 2020 – 2025 sets out the for? management framework for the Dorset and East Devon Coast World Heritage Site, also known as the Jurassic Coast. The management of the site is achieved through a partnership approach. The Jurassic Coast Partnership Plan is a requirement of UNESCO and the UK Government for managing the World Heritage Site. It is a public document which outlines the aims, policies and priority objectives for managing the Site for the next five years. It is the framework that looks after the Jurassic Coast helping to facilitate collaboration and provide a strategic context for investment and action. Who does this policy local communities affect? businesses, landowners authorities, utilities other organisations and groups operating within or with an interest in the area Keywords World Heritage Site (WHS) Jurassic Coast Dorset Devon Heritage Author Name: Bridget Betts Job Title: Environment Advice Manager Tel: 01035 224760 Email: [email protected] Does this policy This plan is a formal requirement of both UNESCO and the UK relate to any laws? Government for managing the World Heritage Site. Is this policy linked to Neighbourhood Plans any other Dorset Local Plans Council policies? Minerals and Waste Local Plan AONB Management Plans Shoreline Management Plans Dorset Coastal Pollution Plan Equality Impact Implementation of policies and actions as contained in the Partnership Assessment (EqIA) Plan, or related research initiatives and consultations should consider audiences carefully. -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

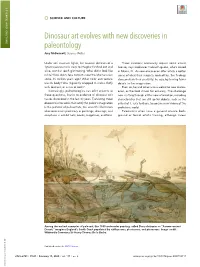

Dinosaur Art Evolves with New Discoveries in Paleontology Amy Mcdermott, Science Writer

SCIENCE AND CULTURE SCIENCE AND CULTURE Dinosaur art evolves with new discoveries in paleontology Amy McDermott, Science Writer Under soft museum lights, the massive skeleton of a Those creations necessarily require some artistic Tyrannosaurus rex is easy to imagine fleshed out and license, says freelancer Gabriel Ugueto, who’s based alive, scimitar teeth glimmering. What did it look like in Miami, FL. As new discoveries offer artists a better in life? How did its face contort under the Montana sun sense of what their subjects looked like, the findings some 66 million years ago? What color and texture also constrain their creativity, he says, by leaving fewer was its body? Was it gauntly wrapped in scales, fluffy details to the imagination. with feathers, or a mix of both? Even so, he and other artists welcome new discov- Increasingly, paleontologists can offer answers to eries, as the field strives for accuracy. The challenge these questions, thanks to evidence of dinosaur soft now is sifting through all this new information, including tissues discovered in the last 30 years. Translating those characteristics that are still up for debate, such as the discoveries into works that satisfy the public’simagination extent of T. rex’s feathers, to conjure new visions of the is the purview of paleoartists, the scientific illustrators prehistoric world. who reconstruct prehistory in paintings, drawings, and Paleoartists often have a general science back- sculptures in exhibit halls, books, magazines, and films. ground or formal artistic training, although career Among the earliest examples of paleoart, this 1830 watercolor painting, called Duria Antiquior or “A more ancient Dorset,” imagines England’s South Coast populated by ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaurs. -

The 'Red Coast'

The ‘Red Coast’ - Exmouth to Sidmouth Place To Walk Location & Access: The route is described from Exmouth to Sidmouth, but could be reversed. Exmouth can be reached via A376 road from Exeter. There is also a regular train link from Exeter Central Station and a regular bus service (number 57) from Exeter. There is plenty of parking in the town of Exmouth, and this walk begins at the car park close to the sea front to east of town - past the Maer recreation ground, and by the lifeboat station at GR SY0121 8000. At the completion of the walk, a return bus (number 57) is available from Sidmouth. Hern Point Rock, Ladram Bay Key Geography: Stunning section of the South West Coast Path - part of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. SSSI, Triassic geology, spits, steep cliffs, coastal erosion, landslips, sea stacks. Description: This walk of 12.5 miles (20 km) covers a stunning section of the 95 miles Jurassic Coast, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Its geology includes Permian and Triassic rocks overlain in part by rocks from the Cretaceous Period. It is informally known as the ‘Red Coast’ due to the colour of the cliffs. From the car park, there is a brief moment to admire the sandy beach of Exmouth before making for the cliffs at eastern end of esplanade. Here, the cliffs of Rodney Point give the first decent view of the red geology. From here, the path climbs to Orcombe Point, where it is possible to stop and take a look at the geoneedle, a monument that marks the start of the Jurassic Coast. -

I Think It a Very Good Idea to Introduce a Cafe and Perhaps Other Mobile Outlets at the Space at Orcombe Point

It should be dog friendly. Recommend we look at the Venus Beach cafe at Bigbury and Blackpool Sands. You should look at the cafe in Swanage at the western end of the promenade near the pier. Starting as a temporary building it has developed into something more permanent with some hard fixed seating based on the kiosk principle with serving hatches. They sell seafood snacks in small plastic dishes with white wine or beer. There are ample bins for disposal of dishes. They do not use glass in case of breakages in a seaside environment. I think it a very good idea to introduce a cafe and perhaps other mobile outlets at the space at Orcombe Point. A cafe selling good quality hot drinks (Yorkshire tea, real coffee, hot chocolate), cold drinks, sandwiches/paninis, home-made cakes and ice cream, alongside lavatory/washing facilities. Another outlet alongside could perhaps sell good quality hot snacks. Not too much to ask! It would be nice to see a cafe/restaurant on similar lines to The Longboat at Budleigh But in the short term we do need to have some refreshment outlet for the summer. Very good to read the piece in relation to the desire to see Café facilities at Orcombe Point. It's not clear from the article if the council are building and then letting or whether you are expecting an owner to come forward with capital monies? Opening up debate with the public is always welcome however they aren't spending their own money and I suspect the wish list will be quite lengthy! There may be a mismatch between the wants of the public and the potential for an individual to get a return on their investment if the expectations are too great to meet? I'm very positive about our town and the visitor experience so if I can help I would be more than willing to do so.