January, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSMS General Assembly Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Annual

Colorado Springs Mineralogical Society Founded in 1936 Lazard Cahn Honorary President December 2018 PICK&PACK Vol 58 .. Number #10 Inside this Issue: CSMS General Assembly CSMS Calendar Pg. 2 Kansas Pseudo- Morphs: Pg. 4 Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Limonite After Pyrite Duria Antiquior: A Annual Christmas Party 19th Century Fore- Pg. 7 runner of Paleoart CSMS Rockhounds of Pg. 9 the Year & 10 Pebble Pups Pg10 **In case of inclement weather, please call** Secretary’s Spot Pg11 Mt. Carmel Veteran’s Service Center 719 309-4714 Classifieds Pg17 Annual Christmas Party Details Please mark your calendars and plan to attend the annual Christmas Party at the Mt. Carmel Veteran's Service Center.on Thursday, December 20, at 7PM. We will provide roast turkey and baked ham as well as Bill Arnson's chili. Members whose last names begin with A--P, please bring a side dish to share. Those whose last names begin with Q -- Z, please bring a dessert to share. There will be a gift exchange for those who want to participate. Please bring a wrapped hobby-related gift valued at $10.00 or less to exchange. We will have a short business meeting to vote on some bylaw changes, and to elect next year's Board of Directors. The Board candidates are as follows: President: Sharon Holte Editor: Taylor Harper Vice President: John Massie Secretary: ?????? Treasurer: Ann Proctor Member-at-Large: Laurann Briding Membership Secretary: Adelaide Barr Member-at Large: Bill Arnson Past president: Ernie Hanlon We are in desperate need of a secretary to serve on the Board. -

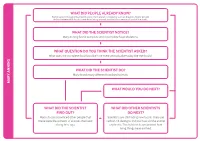

What Did the Scientist Notice? What Question Do You Think

WHAT DID PEOPLE ALREADY KNOW? Some people thought that fossils came from ancient creatures such as dragons. Some people did not believe that fossils came from living animals or plants but were just part of the rocks. WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST NOTICE? Mary Anning found complete and incomplete fossil skeletons. WHAT QUESTION DO YOU THINK THE SCIENTIST ASKED? What does the complete fossil look like? Are there animals alive today like the fossils? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST DO? Mary found many different fossilised animals. MARY ANNING MARY WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST WHAT DID OTHER SCIENTISTS FIND OUT? DO NEXT? Mary’s fossils convinced other people that Scientists are still finding new fossils. They use these were the remains of animals that lived carbon-14 dating to find out how old the animal a long time ago. or plant is. This helps us to understand how living things have evolved. s 1823 / 1824 1947 Mary Anning (1823) discovered a nearly complete plesiosaur Carbon-14 dating enables scientists to determine the age of a formerly skeleton at Lyme Regis. living thing more accurately. When a Tail fossils of a baby species William Conybeare (1824) living organism dies, it stops taking in of Coelurosaur, fully People often found fossils on the beach described Mary’s plesiosaur to the new carbon. Measuring the amount preserved in amber including and did not know what they were, so Geographical Society. They debated of 14C in a fossil sample provides soft tissue, were found in 2016 BEFORE 1800 BEFORE gave them interesting names such as whether it was a fake, but Mary was information that can be used to Myanmar. -

Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) Was One of the First Fossil Collectors

Geology Section: history, interests and the importance of Devon‟s geology Malcolm Hart [Vice-Chair Geology Section] School of Geography, Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Plymouth Devonshire Association, Forum, Sidmouth, March 2020 Slides: 3 – 13 South-West England people; 14 – 25 Our northward migration; 24 – 33 Climate change: a modern problem; 34 – 50 Our geoscience heritage: Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site and the English Riviera UNESCO Global Geopark; 51 – 53 Summary and perspectives When we look at the natural landscape it can appear almost un- changing – even in the course of a life- time. William Smith (1769–1839) was a practical engineer, who used geology in an applied way. He recognised that the fossils he found could indicate the „stratigraphy‟ of the rocks that his work encountered. His map was produced in 1815. Images © Geological Society of London Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) was one of the first fossil collectors. At the time the area was being quarried, though features such as the „ammonite pavement‟ were left for science. Image © Geological Society of London Images © National Museum, Wales Sir Henry De La Beche (1796‒1855) was an extraordinary individual. He wrote on the geology of Devon, Cornwall and Somerset, while living in Lyme Regis. He studied the local geology and created, in Duria Antiquior (a more ancient Dorset) the first palaeoecological reconstruction. He was often ridiculed for this! He was also the first Director of the British Geological Survey. His suggestion, in 1839, that the rocks of Devonshire and Cornwall were „distinctive‟ led to the creation of the Devonian System in 1840. -

Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19Th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology

Headwaters Volume 26 Article 14 2009 Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters Part of the Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2009) "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology," Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Headwaters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LARRY E. DAVIS Mary Anning of Lyme Regis 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Ludwig Leichhardt, a 19th century German explorer noted in a letter, “… we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of Palaeontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression …” (Aurousseau, 1968). Gideon Mantell, a 19th century British palaeontologist, made a less flattering remark when he wrote in his journal, “… sallied out in quest of Mary An- ning, the geological lioness … we found her in a little dirt shop with hundreds of specimens piled around her in the greatest disorder. She, the presiding Deity, a prim, pedantic vinegar looking female; shred, and rather satirical in her conversation” (Curwin, 1940). Who was Mary Anning, this Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness (Fig. -

Teacher's Booklet

Ideas and Evidence at the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Teacher’s Booklet Acknowledgements Shawn Peart Secondary Consultant Annette Shelford Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Paul Dainty Great Cornard Upper School Sarah Taylor St. James Middle School David Heap Westley Middle School Thanks also to Dudley Simons for photography and processing of the images of objects and exhibits at the Sedgwick Museum, and to Adrienne Mayor for kindly allowing us to use her mammoth and monster images (see picture credits). Picture Credits Page 8 “Bag of bones” activity adapted from an old resource, source unknown. Page 8 Iguanodon images used in the interpretation of the skeleton picture resource from www.dinohunters.com Page 9 Mammoth skeleton images from ‘The First Fossil Hunters’ by Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press ISBN: 0-691-05863 with kind permission of the author Page 9 Both paintings of Mary Anning from the collections of the Natural History Museum © Natural History Museum, London 1 Page 12 Palaeontologists Picture from the photographic archive of the Sedgwick Museum © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 14 Images of Iguanodon from www.dinohunters.com Page 15 “Duria Antiquior - a more ancient Dorsetshire” by Henry de la Beche from the collection of the National Museums and Galleries of Wales © National Museum of Wales Page 17 Images of Deinotherium giganteum skull cast © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 19 Image of red sandstone slab © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences 2 Introduction Ideas and evidence was introduced as an aspect of school science after the review of the National Curriculum in 2000. Until the advent of the National Strategy for Science it was an area that was often not planned for explicitly. -

An Investigation Into the Graphic Innovations of Geologist Henry T

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche Renee M. Clary Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Clary, Renee M., "Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 127. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/127 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. UNCOVERING STRATA: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE GRAPHIC INNOVATIONS OF GEOLOGIST HENRY T. DE LA BECHE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Renee M. Clary B.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1983 M.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1997 M.Ed., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Renee M. Clary All rights reserved ii Acknowledgments Photographs of the archived documents held in the National Museum of Wales are provided by the museum, and are reproduced with permission. I send a sincere thank you to Mr. Tom Sharpe, Curator, who offered his time and assistance during the research trip to Wales. -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

Dinosaur Art Evolves with New Discoveries in Paleontology Amy Mcdermott, Science Writer

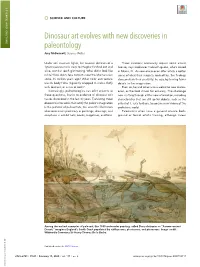

SCIENCE AND CULTURE SCIENCE AND CULTURE Dinosaur art evolves with new discoveries in paleontology Amy McDermott, Science Writer Under soft museum lights, the massive skeleton of a Those creations necessarily require some artistic Tyrannosaurus rex is easy to imagine fleshed out and license, says freelancer Gabriel Ugueto, who’s based alive, scimitar teeth glimmering. What did it look like in Miami, FL. As new discoveries offer artists a better in life? How did its face contort under the Montana sun sense of what their subjects looked like, the findings some 66 million years ago? What color and texture also constrain their creativity, he says, by leaving fewer was its body? Was it gauntly wrapped in scales, fluffy details to the imagination. with feathers, or a mix of both? Even so, he and other artists welcome new discov- Increasingly, paleontologists can offer answers to eries, as the field strives for accuracy. The challenge these questions, thanks to evidence of dinosaur soft now is sifting through all this new information, including tissues discovered in the last 30 years. Translating those characteristics that are still up for debate, such as the discoveries into works that satisfy the public’simagination extent of T. rex’s feathers, to conjure new visions of the is the purview of paleoartists, the scientific illustrators prehistoric world. who reconstruct prehistory in paintings, drawings, and Paleoartists often have a general science back- sculptures in exhibit halls, books, magazines, and films. ground or formal artistic training, although career Among the earliest examples of paleoart, this 1830 watercolor painting, called Duria Antiquior or “A more ancient Dorset,” imagines England’s South Coast populated by ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaurs. -

Issue 3 November, 2018 ______

__________The Paleontograph________ A newsletter for those interested in all aspects of Paleontology Volume 7 Issue 3 November, 2018 _________________________________________________________________ From Your Editor Welcome to our latest edition. I've decided to produce a special edition. Since the holidays are just around the corner and books make great gifts, I thought a special book review edition might be nice. Bob writes wonderful, deep reviews of the many titles he reads. Reviews usually bring a wealth of knowledge about the book topic as well as an actual review of the work. I will soon come out with a standard edition filled with articles about specific paleo related topics and news. The Paleontograph was created in 2012 to continue what was originally the newsletter of The New Jersey Paleontological Society. The Paleontograph publishes articles, book reviews, personal accounts, and anything else that relates to Paleontology and fossils. Feel free to submit both technical and non-technical work. We try to appeal to a wide range of people interested in fossils. Articles about localities, specific types of fossils, fossil preparation, shows or events, museum displays, field trips, websites are all welcome. This newsletter is meant to be one by and for the readers. Issues will come out when there is enough content to fill an issue. I encourage all to submit contributions. It will be interesting, informative and fun to read. It can become whatever the readers and contributors want it to be, so it will be a work in progress. TC, January 2012 Edited by Tom Caggiano and distributed at no charge [email protected] PALEONTOGRAPH Volume 7 Issue 3 November 2018 Page 2 Patrons of Paleontology--A Review As you might expect from the chapter titles, this is a Bob Sheridan October 14, 2017 fairly specialized book, which is tilted more toward history than science in general, and then very concerned with large illustrated publications about fossils. -

Education Guide Available for Download

DARWIN’S MYSTERY OF MYSTERIES EDUCATION GUIDE MIRAGE3D PRESENTS NATURAL SELECTION DARWIN’S MYSTERY OF MYSTERIES A FULLDOME IMMERSIVE CINEMATIC EXPERIENCE WRITTEN / DIRECTED BY ROBIN SIP NARRATED BY TONY MAPLES MUSIC BY MARK SLATER PERFORMED BY THE BUDAPEST SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 1 | 24 LEKSTRAAT 156 2515VZ THE HAGUE THE NETHERLANDS +31 (0)70 3457500 360 FULLDOME 3D STEREO 2 | 24 Charles Darwin “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change.” “A man who dares to waste one hour of time has not discovered the value of life.” – Charles Darwin Charles Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, England, on February 12, 1809. His mother died when he was only eight years old. His father was as a medical doctor and his grandfather was a famous botanist, so science had always surrounded him. Charles was especially fond of exploring nature. He grew up with wealth and privilege. In 1825, when he was only sixteen, Darwin enrolled at Edinburgh University. In 1827, he transferred to Christ’s College in Cambridge. He planned to become to a physician like his father until he discovered that he could not stand the sight of blood. His father suggested that he become a minister, but Darwin wanted to study natural history, which he did. In 1831, he obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree and his mentor, botany professor John Stevens Henslow, recommended Darwin for a position as a naturalist on the HMS Beagle. Initially, Darwin’s father opposed the voyage and since he was expected to pay for Darwin’s supplies (microscopes, glassware, p reserving papers, etc.) and his passage, he had the right to do so. -

'The World-Renowned Ichthyosaurus': a Nineteenth-Century Problematic

Journal of Literature and Science Volume 2, No. 1 (2009) ISSN 1754-646XJournal of Literature and Science 2 (2009) Glendening, “Ichthyosaurus”: 23-47 John Glendening, “Ichthyosaurus”: 23-47 ‘The World-Renowned Ichthyosaurus’: A Nineteenth-Century Problematic and Its Representations John Glendening I The first edition in English of Jules Verne’s Voyage au centre de la Terre (1864), published in 1871 as A Journey to the Centre of the Earth , like the original features an epic combat between two enormous marine reptiles but identifies one of them as “the world-renowned ichthyosaurus”.1 One of many alterations this British rendition imposes upon the second, expanded edition of Verne’s novel (1867), the spurious “world-renowned” was added not only to heighten interest, but also, quite likely, to appeal to nationalism since ichthyosaur fossils were first identified, described, and publicized in England. The story of early ichthyosaur discoveries has been told often enough, with recent stress upon the scientific acumen and potential, once downplayed because of gender and class, of fossil collector Mary Anning. 2 At Lyme Regis, Dorset—the epicenter of paleontological shocks and excitement that radiated out to Britain and beyond—beginning in 1811 Anning discovered and excavated the first fossilized ichthyosaur skeletons recognizable as “an important new kind of animal”.3 Her once undervalued scientific credentials, however, represent but one of the ways in which the ichthyosaur of scientific and popular imagination swam in unsettled cultural waters. As the first large prehistoric reptile discovered and identified in England, the ichthyosaur (“fish-lizard”) built upon and furthered the British enthusiasm for natural history, geology, and fossil collecting that flourished especially in the first half of the nineteenth century. -

Fossil Finding Mission

1.b. SCIENCE ACTIVITY: Fossil Finding Mission TIME NEEDED: 1-2 hours AGE: Upper KS2 / Year 5, 6 LEARNING OUTCOMES Knowledge: Fossils and dinosaurs, basic palaeontology Skills: Independent research skills, planning, drawing MATERIALS Sketchbooks, A2 cartridge paper, pencils, rubbers, coloured pencils. ACTIVITY Look at this painting, Duria Antiquior (An Ancient Dorset) by Henry de la Beche (1830), at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duria_Antiquior. It is one of the first scientific paintings based upon the fossils found by Mary Anning in Lyme Regis. All rights reserved. • Choose an animal from the painting. Research the animal online or in books. Try to identify it and draw the animal from the internet / books into your sketchbook. Look closely and see © UKRI 2019 what differences there are between the modern images of these ancient creatures, and Henry’s paintings of them in 1830. Why is this? Henry and Mary spent much time fossil hunting on the beach. Now it’s your turn. Pretend you’re going to Lyme Regis Beach to do some palaeontological research! • Choose one of the animals from ‘Duria Antiquior’ to research on your fossil hunt. British Geological Survey Materials Then plan your trip... • What clues will you look for when you get to the beach? * • What safety procedures will you need to take? • What time of day will you go? • What kit do you need to take with you? • What do you need to survive? Permit Number CP19/081: Contains • What information do you need to have before you go? Make a map of your planned trip. Put in the sea, beach and cliffs using colours and textures.