'The World-Renowned Ichthyosaurus': a Nineteenth-Century Problematic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSMS General Assembly Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Annual

Colorado Springs Mineralogical Society Founded in 1936 Lazard Cahn Honorary President December 2018 PICK&PACK Vol 58 .. Number #10 Inside this Issue: CSMS General Assembly CSMS Calendar Pg. 2 Kansas Pseudo- Morphs: Pg. 4 Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Limonite After Pyrite Duria Antiquior: A Annual Christmas Party 19th Century Fore- Pg. 7 runner of Paleoart CSMS Rockhounds of Pg. 9 the Year & 10 Pebble Pups Pg10 **In case of inclement weather, please call** Secretary’s Spot Pg11 Mt. Carmel Veteran’s Service Center 719 309-4714 Classifieds Pg17 Annual Christmas Party Details Please mark your calendars and plan to attend the annual Christmas Party at the Mt. Carmel Veteran's Service Center.on Thursday, December 20, at 7PM. We will provide roast turkey and baked ham as well as Bill Arnson's chili. Members whose last names begin with A--P, please bring a side dish to share. Those whose last names begin with Q -- Z, please bring a dessert to share. There will be a gift exchange for those who want to participate. Please bring a wrapped hobby-related gift valued at $10.00 or less to exchange. We will have a short business meeting to vote on some bylaw changes, and to elect next year's Board of Directors. The Board candidates are as follows: President: Sharon Holte Editor: Taylor Harper Vice President: John Massie Secretary: ?????? Treasurer: Ann Proctor Member-at-Large: Laurann Briding Membership Secretary: Adelaide Barr Member-at Large: Bill Arnson Past president: Ernie Hanlon We are in desperate need of a secretary to serve on the Board. -

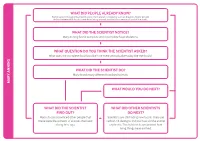

What Did the Scientist Notice? What Question Do You Think

WHAT DID PEOPLE ALREADY KNOW? Some people thought that fossils came from ancient creatures such as dragons. Some people did not believe that fossils came from living animals or plants but were just part of the rocks. WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST NOTICE? Mary Anning found complete and incomplete fossil skeletons. WHAT QUESTION DO YOU THINK THE SCIENTIST ASKED? What does the complete fossil look like? Are there animals alive today like the fossils? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST DO? Mary found many different fossilised animals. MARY ANNING MARY WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST WHAT DID OTHER SCIENTISTS FIND OUT? DO NEXT? Mary’s fossils convinced other people that Scientists are still finding new fossils. They use these were the remains of animals that lived carbon-14 dating to find out how old the animal a long time ago. or plant is. This helps us to understand how living things have evolved. s 1823 / 1824 1947 Mary Anning (1823) discovered a nearly complete plesiosaur Carbon-14 dating enables scientists to determine the age of a formerly skeleton at Lyme Regis. living thing more accurately. When a Tail fossils of a baby species William Conybeare (1824) living organism dies, it stops taking in of Coelurosaur, fully People often found fossils on the beach described Mary’s plesiosaur to the new carbon. Measuring the amount preserved in amber including and did not know what they were, so Geographical Society. They debated of 14C in a fossil sample provides soft tissue, were found in 2016 BEFORE 1800 BEFORE gave them interesting names such as whether it was a fake, but Mary was information that can be used to Myanmar. -

A Mysterious Giant Ichthyosaur from the Lowermost Jurassic of Wales

A mysterious giant ichthyosaur from the lowermost Jurassic of Wales JEREMY E. MARTIN, PEGGY VINCENT, GUILLAUME SUAN, TOM SHARPE, PETER HODGES, MATT WILLIAMS, CINDY HOWELLS, and VALENTIN FISCHER Ichthyosaurs rapidly diversified and colonised a wide range vians may challenge our understanding of their evolutionary of ecological niches during the Early and Middle Triassic history. period, but experienced a major decline in diversity near the Here we describe a radius of exceptional size, collected at end of the Triassic. Timing and causes of this demise and the Penarth on the coast of south Wales near Cardiff, UK. This subsequent rapid radiation of the diverse, but less disparate, specimen is comparable in morphology and size to the radius parvipelvian ichthyosaurs are still unknown, notably be- of shastasaurids, and it is likely that it comes from a strati- cause of inadequate sampling in strata of latest Triassic age. graphic horizon considerably younger than the last definite Here, we describe an exceptionally large radius from Lower occurrence of this family, the middle Norian (Motani 2005), Jurassic deposits at Penarth near Cardiff, south Wales (UK) although remains attributable to shastasaurid-like forms from the morphology of which places it within the giant Triassic the Rhaetian of France were mentioned by Bardet et al. (1999) shastasaurids. A tentative total body size estimate, based on and very recently by Fischer et al. (2014). a regression analysis of various complete ichthyosaur skele- Institutional abbreviations.—BRLSI, Bath Royal Literary tons, yields a value of 12–15 m. The specimen is substantially and Scientific Institution, Bath, UK; NHM, Natural History younger than any previously reported last known occur- Museum, London, UK; NMW, National Museum of Wales, rences of shastasaurids and implies a Lazarus range in the Cardiff, UK; SMNS, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, lowermost Jurassic for this ichthyosaur morphotype. -

Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) Was One of the First Fossil Collectors

Geology Section: history, interests and the importance of Devon‟s geology Malcolm Hart [Vice-Chair Geology Section] School of Geography, Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Plymouth Devonshire Association, Forum, Sidmouth, March 2020 Slides: 3 – 13 South-West England people; 14 – 25 Our northward migration; 24 – 33 Climate change: a modern problem; 34 – 50 Our geoscience heritage: Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site and the English Riviera UNESCO Global Geopark; 51 – 53 Summary and perspectives When we look at the natural landscape it can appear almost un- changing – even in the course of a life- time. William Smith (1769–1839) was a practical engineer, who used geology in an applied way. He recognised that the fossils he found could indicate the „stratigraphy‟ of the rocks that his work encountered. His map was produced in 1815. Images © Geological Society of London Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) was one of the first fossil collectors. At the time the area was being quarried, though features such as the „ammonite pavement‟ were left for science. Image © Geological Society of London Images © National Museum, Wales Sir Henry De La Beche (1796‒1855) was an extraordinary individual. He wrote on the geology of Devon, Cornwall and Somerset, while living in Lyme Regis. He studied the local geology and created, in Duria Antiquior (a more ancient Dorset) the first palaeoecological reconstruction. He was often ridiculed for this! He was also the first Director of the British Geological Survey. His suggestion, in 1839, that the rocks of Devonshire and Cornwall were „distinctive‟ led to the creation of the Devonian System in 1840. -

Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19Th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology

Headwaters Volume 26 Article 14 2009 Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters Part of the Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2009) "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology," Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Headwaters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LARRY E. DAVIS Mary Anning of Lyme Regis 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Ludwig Leichhardt, a 19th century German explorer noted in a letter, “… we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of Palaeontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression …” (Aurousseau, 1968). Gideon Mantell, a 19th century British palaeontologist, made a less flattering remark when he wrote in his journal, “… sallied out in quest of Mary An- ning, the geological lioness … we found her in a little dirt shop with hundreds of specimens piled around her in the greatest disorder. She, the presiding Deity, a prim, pedantic vinegar looking female; shred, and rather satirical in her conversation” (Curwin, 1940). Who was Mary Anning, this Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness (Fig. -

Teacher's Booklet

Ideas and Evidence at the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Teacher’s Booklet Acknowledgements Shawn Peart Secondary Consultant Annette Shelford Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Paul Dainty Great Cornard Upper School Sarah Taylor St. James Middle School David Heap Westley Middle School Thanks also to Dudley Simons for photography and processing of the images of objects and exhibits at the Sedgwick Museum, and to Adrienne Mayor for kindly allowing us to use her mammoth and monster images (see picture credits). Picture Credits Page 8 “Bag of bones” activity adapted from an old resource, source unknown. Page 8 Iguanodon images used in the interpretation of the skeleton picture resource from www.dinohunters.com Page 9 Mammoth skeleton images from ‘The First Fossil Hunters’ by Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press ISBN: 0-691-05863 with kind permission of the author Page 9 Both paintings of Mary Anning from the collections of the Natural History Museum © Natural History Museum, London 1 Page 12 Palaeontologists Picture from the photographic archive of the Sedgwick Museum © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 14 Images of Iguanodon from www.dinohunters.com Page 15 “Duria Antiquior - a more ancient Dorsetshire” by Henry de la Beche from the collection of the National Museums and Galleries of Wales © National Museum of Wales Page 17 Images of Deinotherium giganteum skull cast © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 19 Image of red sandstone slab © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences 2 Introduction Ideas and evidence was introduced as an aspect of school science after the review of the National Curriculum in 2000. Until the advent of the National Strategy for Science it was an area that was often not planned for explicitly. -

Ichthyosaur Species Valid Taxa Acamptonectes Fischer Et Al., 2012: Acamptonectes Densus Fischer Et Al., 2012, Lower Cretaceous, Eng- Land, Germany

Ichthyosaur species Valid taxa Acamptonectes Fischer et al., 2012: Acamptonectes densus Fischer et al., 2012, Lower Cretaceous, Eng- land, Germany. Aegirosaurus Bardet and Fernández, 2000: Aegirosaurus leptospondylus (Wagner 1853), Upper Juras- sic–Lower Cretaceous?, Germany, Austria. Arthropterygius Maxwell, 2010: Arthropterygius chrisorum (Russell, 1993), Upper Jurassic, Canada, Ar- gentina?. Athabascasaurus Druckenmiller and Maxwell, 2010: Athabascasaurus bitumineus Druckenmiller and Maxwell, 2010, Lower Cretaceous, Canada. Barracudasauroides Maisch, 2010: Barracudasauroides panxianensis (Jiang et al., 2006), Middle Triassic, China. Besanosaurus Dal Sasso and Pinna, 1996: Besanosaurus leptorhynchus Dal Sasso and Pinna, 1996, Middle Triassic, Italy, Switzerland. Brachypterygius Huene, 1922: Brachypterygius extremus (Boulenger, 1904), Upper Jurassic, Engand; Brachypterygius mordax (McGowan, 1976), Upper Jurassic, England; Brachypterygius pseudoscythius (Efimov, 1998), Upper Jurassic, Russia; Brachypterygius alekseevi (Arkhangelsky, 2001), Upper Jurassic, Russia; Brachypterygius cantabridgiensis (Lydekker, 1888a), Lower Cretaceous, England. Californosaurus Kuhn, 1934: Californosaurus perrini (Merriam, 1902), Upper Triassic USA. Callawayia Maisch and Matzke, 2000: Callawayia neoscapularis (McGowan, 1994), Upper Triassic, Can- ada. Caypullisaurus Fernández, 1997: Caypullisaurus bonapartei Fernández, 1997, Upper Jurassic, Argentina. Chaohusaurus Young and Dong, 1972: Chaohusaurus geishanensis Young and Dong, 1972, Lower Trias- sic, China. -

An Investigation Into the Graphic Innovations of Geologist Henry T

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche Renee M. Clary Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Clary, Renee M., "Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 127. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/127 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. UNCOVERING STRATA: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE GRAPHIC INNOVATIONS OF GEOLOGIST HENRY T. DE LA BECHE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Renee M. Clary B.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1983 M.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1997 M.Ed., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Renee M. Clary All rights reserved ii Acknowledgments Photographs of the archived documents held in the National Museum of Wales are provided by the museum, and are reproduced with permission. I send a sincere thank you to Mr. Tom Sharpe, Curator, who offered his time and assistance during the research trip to Wales. -

January, 2019

Lake George Gem & Mineral Club January, 2019 Program for the Month: Saturday, January 12, 2019, 10:00 a.m. Dinosaur Tracks presented by Paul Combs For a long time, people looked at dinosaur tracks as nothing more than "curiosities". Even paleontologists used them as door stops and paper weights, or gave them away to friends. No more. About 30 years ago, the study of dinosaur tracks really took off, and the discoveries are nothing short of amazing. In that short time, we have discovered a lot about how fast different dinosaurs walked or ran, how they stood, what they ate, how they hunted, that they swam, how they courted their mates, how they raised their young, that they traveled in herds, and much more. And more track sites are being discovered in the USA and around the world every year. Paul Combs will explain the techniques that scientists are using and what all this work is teaching us. For instance, Steven Spielberg used this new information in the making of the "Jurassic Park" series of films. Some of these discoveries are happening right now, at sites here in Colorado! Silent Auction: We need donations for the silent auction! If you have “extras”, whether minerals, fossils, books, or other items, and if you have a label saying what the item is and where it came from, we can use it. If not, bring some cash and be prepared to help support Club activities, including scholarships, Pebble Pups, and other items. From the President-elect -- Richard Kawamoto: A Happy New Year wish and a hearty welcome to another exciting year of activities with the Lake George Gem & Mineral Club. -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

Macropredatory Ichthyosaur from the Middle Triassic and the Origin of Modern Trophic Networks

Macropredatory ichthyosaur from the Middle Triassic and the origin of modern trophic networks Nadia B. Fröbischa,1, Jörg Fröbischa,1, P. Martin Sanderb,1,2, Lars Schmitzc,1,2,3, and Olivier Rieppeld aMuseum für Naturkunde, Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 10115 Berlin, Germany; bSteinmann Institute of Geology, Mineralogy, and Paleontology, Division of Paleontology, University of Bonn, 53115 Bonn, Germany; cDepartment of Evolution and Ecology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; and dDepartment of Geology, The Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605 Edited by Neil H. Shubin, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved December 5, 2012 (received for review October 8, 2012) The biotic recovery from Earth’s most severe extinction event at the Holotype and Only Specimen. The Field Museum of Natural His- Permian-Triassic boundary largely reestablished the preextinction tory (FMNH) contains specimen PR 3032, a partial skeleton structure of marine trophic networks, with marine reptiles assuming including most of the skull (Fig. 1) and axial skeleton, parts of the predator roles. However, the highest trophic level of today’s the pelvic girdle, and parts of the hind fins. marine ecosystems, i.e., macropredatory tetrapods that forage on prey of similar size to their own, was thus far lacking in the Paleozoic Horizon and Locality. FMNH PR 3032 was collected in 2008 from the and early Mesozoic. Here we report a top-tier tetrapod predator, middle Anisian Taylori Zone of the Fossil Hill Member of the Favret a very large (>8.6 m) ichthyosaur from the early Middle Triassic Formation at Favret Canyon, Augusta Mountains, Pershing County, (244 Ma), of Nevada. -

First Amphibian Ichthyosaur Fossil Found

First amphibian ichthyosaur fossil found An ancient marine reptile with seal-like flippers may have been adapted to life on the land as well as in the sea, scientists believe. The 250-million-year-old creature is the first amphibious ichthyosaur known. Its relatives were dolphin-like creatures that swam in the oceans at the time of the dinosaurs. They are thought to have had terrestrial ancestors, but previously no fossils had come to light marking the transition of ichthyosaurs from land to sea. “Now we have this fossil showing the transition,” said lead scientist Professor Ryosuke Motani, from the University of California at Davis who reported the discovery in the journal Nature. At 1.5 feet long, Cartorhynchus lenticarpus was also the smallest known ichthyosaur. Its fossil remains found in Anhui Province, China, date from the start of the Triassic period about 248 million years ago. As well as big flippers, Cartorhynchus had flexible wrists which would have been essential for movement on the ground. While most ichthyosaurs have long beak-like snouts, the new specimen possessed a short nose that may have been adapted to suction feeding. Its body also contained thicker bones than other ichthyosaurs. This supports the theory that most marine reptiles that left the land first grew heavier to help them swim through rough coastal waves. The animal lived about 4 million years after the worst mass extinction in history, shedding light on how long it took for life on Earth to recover. The Permian-Triassic extinction, known as the “Great Dying”, wiped out 96% of all species and may have been linked to global warming.