Is Oculudentavis a Bird Or Even Archosaur?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript

Page 1 Dinosaur Wars Program Transcript Narrator: For more than a century, Americans have had a love affair with dinosaurs. Extinct for millions of years, they were barely known until giant, fossil bones were discovered in the mid-nineteenth century. Two American scientists, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, led the way to many of these discoveries, at the forefront of the young field of paleontology. Jacques Gauthier, Paleontologist: Every iconic dinosaur every kid grows up with, apatosaurus, triceratops, stegosaurus, allosaurus, these guys went out into the American West and they found that stuff. Narrator: Cope and Marsh shed light on the deep past in a way no one had ever been able to do before. They unearthed more than 130 dinosaur species and some of the first fossil evidence supporting Darwin’s new theory of evolution. Mark Jaffe, Writer: Unfortunately there was a more sordid element, too, which was their insatiable hatred for each other, which often just baffled and exasperated everyone around them. Peter Dodson, Paleontologist: They began life as friends. Then things unraveled… and unraveled in quite a spectacular way. Narrator: Cope and Marsh locked horns for decades, in one of the most bitter scientific rivalries in American history. Constantly vying for leadership in their young field, they competed ruthlessly to secure gigantic bones in the American West. They put American science on the world stage and nearly destroyed one another in the process. Page 2 In the summer of 1868, a small group of scientists boarded a Union Pacific train for a sightseeing excursion through the heart of the newly-opened American West. -

8. Archosaur Phylogeny and the Relationships of the Crocodylia

8. Archosaur phylogeny and the relationships of the Crocodylia MICHAEL J. BENTON Department of Geology, The Queen's University of Belfast, Belfast, UK JAMES M. CLARK* Department of Anatomy, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA Abstract The Archosauria include the living crocodilians and birds, as well as the fossil dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and basal 'thecodontians'. Cladograms of the basal archosaurs and of the crocodylomorphs are given in this paper. There are three primitive archosaur groups, the Proterosuchidae, the Erythrosuchidae, and the Proterochampsidae, which fall outside the crown-group (crocodilian line plus bird line), and these have been defined as plesions to a restricted Archosauria by Gauthier. The Early Triassic Euparkeria may also fall outside this crown-group, or it may lie on the bird line. The crown-group of archosaurs divides into the Ornithosuchia (the 'bird line': Orn- ithosuchidae, Lagosuchidae, Pterosauria, Dinosauria) and the Croco- dylotarsi nov. (the 'crocodilian line': Phytosauridae, Crocodylo- morpha, Stagonolepididae, Rauisuchidae, and Poposauridae). The latter three families may form a clade (Pseudosuchia s.str.), or the Poposauridae may pair off with Crocodylomorpha. The Crocodylomorpha includes all crocodilians, as well as crocodi- lian-like Triassic and Jurassic terrestrial forms. The Crocodyliformes include the traditional 'Protosuchia', 'Mesosuchia', and Eusuchia, and they are defined by a large number of synapomorphies, particularly of the braincase and occipital regions. The 'protosuchians' (mainly Early *Present address: Department of Zoology, Storer Hall, University of California, Davis, Cali- fornia, USA. The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods, Volume 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds (ed. M.J. Benton), Systematics Association Special Volume 35A . pp. 295-338. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1988. -

H17 the Descent of Birds < Neornithines, Archaeopteryx

LIFE OF THE MESOZOIC ERA 465 h17 The descent of birds < neornithines, Archaeopteryx, Solnhofen Lms > Alfred, Lord Tennyson / once solved an enigma: When is an / eider [a seaduck] most like a merganser [a lake and river duck]? / He lived long enough to forget the answer. —an anonymous clerihew.1 All eighteen species of penguin live in the Southern Hemisphere. ... The descendants of a common ancestor, sharing common ground. ... ‘This bond, on my [Darwin’s] theory, is simple inheritance.’2 Bird evolution during the Cenozoic has been varied and rapid in the beak but not in the body. For example, Hawaiian Island bird arrivals beginning 5 Ma (million years ago) have evolved to new species with beaks specialized to feed on various flowers and seeds but their bodies have changed so little that the various pioneer-bird stocks are easy to identify. With that perspective, bird varieties distinctive in the beak as owls, hawks, penguins, ducks, flamingos, and parrots, are likely to have diverged in very ancient times. Ducks, albeit primitive ones such as web footed Presbyornis, which could wade but not paddle, already existed in the bird diversity of the Eocene when giant “terror birds,” such as Diatrema, patrolled the ground. Feathers are made mostly of beta keratin, a strong light-weight material. Bird feathers are modified scales which extrude from cells that line skin follicles. The shape and color of the feather so formed can change during the birds growth (say, a downy feather in youth and a stiff feather in adulthood) and by seasonal molts (say, a white feather in the winter and a colored feather for times of courting).3 All birds of the Cenozoic (30 orders) are characterized by toothless jaws and have a pair of elongated foot bones that are partially fused from the bottom up. -

Broad-Tailed Hummingbird Coloration and Sun Orientation 1

1 Broad-tailed hummingbird coloration and sun orientation 1 Two ways to display: male hummingbirds show different 2 color-display tactics based on sun orientation 3 Running header: Broad-tailed hummingbird coloration and sun orientation 4 5 Richard K. Simpson1* and Kevin J. McGraw1 6 1School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-4501 7 *Corresponding Author. Email: [email protected]; Phone: (480) 965-2593 8 9 ABSTRACT 10 Animals exhibit a diversity of ornaments and courtship behaviors, which often co- 11 occur and are used for communication. The sensory drive hypothesis states that these 12 traits evolved and vary due to interactions with each other, the environment, and signal 13 receiver. However, interactions between colorful ornaments and courtship behaviors, 14 specifically in relation to environmental variation, remain poorly understood. We studied 15 male iridescent plumage (gorgets), display behavior, and sun orientation during courtship 16 flights (shuttle displays) in broad-tailed hummingbirds (Selasphorus platycercus), to 17 understand how these traits interact in both space and time to produce the perceived 18 coloration of males. We also tested how gorget coloration varies among males based on 19 their plumage, behavioral, and morphological characteristics. In contrast with previous 20 work on other animals, we found that displaying males did not directionally face the sun, 21 but instead displayed on a continuum of solar orientation angles. The gorgets of males 22 who tended to face the sun during their displays appeared flashier (i.e. exhibited greater 23 color/brightness changes), brighter, and more colorful, whereas the gorgets of males who 2 Broad-tailed hummingbird coloration and sun orientation 24 tended to not face the sun were more consistently reflective (i.e. -

Tiny Fossil Sheds Light on Miniaturization of Birds

Retraction Tiny fossil sheds light on miniaturization of birds Roger B. J. Benson Nature 579, 199–200 (2020) In view of the fact that the authors of ‘Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous period of Myanmar‘ (L. Xing et al. Nature 579, 245–249; 2020) are retracting their report, I wish to retract this News & Views article, which dealt with this study and was based on the accuracy and reproducibility of their data. Nature | 22 July 2020 ©2020 Spri nger Nature Li mited. All rights reserved. drives the assembly of DNA-PK and stimulates regulation of protein synthesis. And, although 3. Dragon, F. et al. Nature 417, 967–970 (2002). its catalytic activity in vitro, although does so further studies are required, we might have 4. Adelmant, G. et al. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 11, 411–421 (2012). much less efficiently than can DNA. taken a step closer to deciphering the 5. Britton, S., Coates, J. & Jackson, S. P. J. Cell Biol. 202, Taken together, these observations suggest mysterious ribosomopathies. 579–595 (2013). a model in which KU recruits DNA-PKcs to the 6. Barandun, J. et al. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 24, 944–953 (2017). small-subunit processome. In the case of Alan J. Warren is at the Cambridge Institute 7. Ma, Y. et al. Cell 108, 781–794 (2002). kinase-defective DNA-PK, the mutant enzyme’s for Medical Research, Hills Road, Cambridge 8. Yin, X. et al. Cell Res. 27, 1341–1350 (2017). inability to regulate its own activity gives the CB2 OXY, UK. 9. Sharif, H. et al. -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Basal Ornithischia (Reptilia, Dinosauria)

A PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE BASAL ORNITHISCHIA (REPTILIA, DINOSAURIA) Marc Richard Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2007 Committee: Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor Don C. Steinker Daniel M. Pavuk © 2007 Marc Richard Spencer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor The placement of Lesothosaurus diagnosticus and the Heterodontosauridae within the Ornithischia has been problematic. Historically, Lesothosaurus has been regarded as a basal ornithischian dinosaur, the sister taxon to the Genasauria. Recent phylogenetic analyses, however, have placed Lesothosaurus as a more derived ornithischian within the Genasauria. The Fabrosauridae, of which Lesothosaurus was considered a member, has never been phylogenetically corroborated and has been considered a paraphyletic assemblage. Prior to recent phylogenetic analyses, the problematic Heterodontosauridae was placed within the Ornithopoda as the sister taxon to the Euornithopoda. The heterodontosaurids have also been considered as the basal member of the Cerapoda (Ornithopoda + Marginocephalia), the sister taxon to the Marginocephalia, and as the sister taxon to the Genasauria. To reevaluate the placement of these taxa, along with other basal ornithischians and more derived subclades, a phylogenetic analysis of 19 taxonomic units, including two outgroup taxa, was performed. Analysis of 97 characters and their associated character states culled, modified, and/or rescored from published literature based on published descriptions, produced four most parsimonious trees. Consistency and retention indices were calculated and a bootstrap analysis was performed to determine the relative support for the resultant phylogeny. The Ornithischia was recovered with Pisanosaurus as its basalmost member. -

Perinate and Eggs of a Giant Caenagnathid Dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Central China

ARTICLE Received 29 Jul 2016 | Accepted 15 Feb 2017 | Published 9 May 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms14952 OPEN Perinate and eggs of a giant caenagnathid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of central China Hanyong Pu1, Darla K. Zelenitsky2, Junchang Lu¨3, Philip J. Currie4, Kenneth Carpenter5,LiXu1, Eva B. Koppelhus4, Songhai Jia1, Le Xiao1, Huali Chuang1, Tianran Li1, Martin Kundra´t6 & Caizhi Shen3 The abundance of dinosaur eggs in Upper Cretaceous strata of Henan Province, China led to the collection and export of countless such fossils. One of these specimens, recently repatriated to China, is a partial clutch of large dinosaur eggs (Macroelongatoolithus) with a closely associated small theropod skeleton. Here we identify the specimen as an embryo and eggs of a new, large caenagnathid oviraptorosaur, Beibeilong sinensis. This specimen is the first known association between skeletal remains and eggs of caenagnathids. Caenagnathids and oviraptorids share similarities in their eggs and clutches, although the eggs of Beibeilong are significantly larger than those of oviraptorids and indicate an adult body size comparable to a gigantic caenagnathid. An abundance of Macroelongatoolithus eggs reported from Asia and North America contrasts with the dearth of giant caenagnathid skeletal remains. Regardless, the large caenagnathid-Macroelongatoolithus association revealed here suggests these dinosaurs were relatively common during the early Late Cretaceous. 1 Henan Geological Museum, Zhengzhou 450016, China. 2 Department of Geoscience, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 1N4. 3 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China. 4 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E9. 5 Prehistoric Museum, Utah State University, 155 East Main Street, Price, Utah 84501, USA. -

Wildlife Ecology Provincial Resources

MANITOBA ENVIROTHON WILDLIFE ECOLOGY PROVINCIAL RESOURCES !1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank: Olwyn Friesen (PhD Ecology) for compiling, writing, and editing this document. Subject Experts and Editors: Barbara Fuller (Project Editor, Chair of Test Writing and Education Committee) Lindsey Andronak (Soils, Research Technician, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) Jennifer Corvino (Wildlife Ecology, Senior Park Interpreter, Spruce Woods Provincial Park) Cary Hamel (Plant Ecology, Director of Conservation, Nature Conservancy Canada) Lee Hrenchuk (Aquatic Ecology, Biologist, IISD Experimental Lakes Area) Justin Reid (Integrated Watershed Management, Manager, La Salle Redboine Conservation District) Jacqueline Monteith (Climate Change in the North, Science Consultant, Frontier School Division) SPONSORS !2 Introduction to wildlife ...................................................................................7 Ecology ....................................................................................................................7 Habitat ...................................................................................................................................8 Carrying capacity.................................................................................................................... 9 Population dynamics ..............................................................................................................10 Basic groups of wildlife ................................................................................11 -

Insight Into the Evolution of Avian Flight from a New Clade of Early

J. Anat. (2006) 208, pp287–308 IBlackwnell Publishing sLtd ight into the evolution of avian flight from a new clade of Early Cretaceous ornithurines from China and the morphology of Yixianornis grabaui Julia A. Clarke,1 Zhonghe Zhou2 and Fucheng Zhang2 1Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Abstract In studies of the evolution of avian flight there has been a singular preoccupation with unravelling its origin. By con- trast, the complex changes in morphology that occurred between the earliest form of avian flapping flight and the emergence of the flight capabilities of extant birds remain comparatively little explored. Any such work has been limited by a comparative paucity of fossils illuminating bird evolution near the origin of the clade of extant (i.e. ‘modern’) birds (Aves). Here we recognize three species from the Early Cretaceous of China as comprising a new lineage of basal ornithurine birds. Ornithurae is a clade that includes, approximately, comparatively close relatives of crown clade Aves (extant birds) and that crown clade. The morphology of the best-preserved specimen from this newly recognized Asian diversity, the holotype specimen of Yixianornis grabaui Zhou and Zhang 2001, complete with finely preserved wing and tail feather impressions, is used to illustrate the new insights offered by recognition of this lineage. Hypotheses of avian morphological evolution and specifically proposed patterns of change in different avian locomotor modules after the origin of flight are impacted by recognition of the new lineage. -

Phylocode: a Phylogenetic Code of Biological Nomenclature

PhyloCode: A Phylogenetic Code of Biological Nomenclature Philip D. Cantino and Kevin de Queiroz (equal contributors; names listed alphabetically) Advisory Group: William S. Alverson, David A. Baum, Harold N. Bryant, David C. Cannatella, Peter R. Crane, Michael J. Donoghue, Torsten Eriksson*, Jacques Gauthier, Kenneth Halanych, David S. Hibbett, David M. Hillis, Kathleen A. Kron, Michael S. Y. Lee, Alessandro Minelli, Richard G. Olmstead, Fredrik Pleijel*, J. Mark Porter, Heidi E. Robeck, Greg W. Rouse, Timothy Rowe*, Christoffer Schander, Per Sundberg, Mikael Thollesson, and Andre R. Wyss. *Chaired a committee that authored a portion of the current draft. Most recent revision: April 8, 2000 1 Table of Contents Preface Preamble Division I. Principles Division II. Rules Chapter I. Taxa Article 1. The Nature of Taxa Article 2. Clades Article 3. Hierarchy and Rank Chapter II. Publication Article 4. Publication Requirements Article 5. Publication Date Chapter III. Names Section 1. Status Article 6 Section 2. Establishment Article 7. General Requirements Article 8. Registration Chapter IV. Clade Names Article 9. General Requirements for Establishment of Clade Names Article 10. Selection of Clade Names for Establishment Article 11. Specifiers and Qualifying Clauses Chapter V. Selection of Accepted Names Article 12. Precedence Article 13. Homonymy Article 14. Synonymy Article 15. Conservation Chapter VI. Provisions for Hybrids Article 16. Chapter VII. Orthography Article 17. Orthographic Requirements for Establishment Article 18. Subsequent Use and Correction of Established Names Chapter VIII. Authorship of Names Article 19. Chapter IX. Citation of Authors and Registration Numbers Article 20. Chapter X. Governance Article 21. Glossary Table 1. Equivalence of Nomenclatural Terms Appendix A. -

Cranial Anatomy of Allosaurus Jimmadseni, a New Species from the Lower Part of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western North America

Cranial anatomy of Allosaurus jimmadseni, a new species from the lower part of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western North America Daniel J. Chure1,2,* and Mark A. Loewen3,4,* 1 Dinosaur National Monument (retired), Jensen, UT, USA 2 Independent Researcher, Jensen, UT, USA 3 Natural History Museum of Utah, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA 4 Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Allosaurus is one of the best known theropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic and a crucial taxon in phylogenetic analyses. On the basis of an in-depth, firsthand study of the bulk of Allosaurus specimens housed in North American institutions, we describe here a new theropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Western North America, Allosaurus jimmadseni sp. nov., based upon a remarkably complete articulated skeleton and skull and a second specimen with an articulated skull and associated skeleton. The present study also assigns several other specimens to this new species, Allosaurus jimmadseni, which is characterized by a number of autapomorphies present on the dermal skull roof and additional characters present in the postcrania. In particular, whereas the ventral margin of the jugal of Allosaurus fragilis has pronounced sigmoidal convexity, the ventral margin is virtually straight in Allosaurus jimmadseni. The paired nasals of Allosaurus jimmadseni possess bilateral, blade-like crests along the lateral margin, forming a pronounced nasolacrimal crest that is absent in Allosaurus fragilis. Submitted 20 July 2018 Accepted 31 August 2019 Subjects Paleontology, Taxonomy Published 24 January 2020 Keywords Allosaurus, Allosaurus jimmadseni, Dinosaur, Theropod, Morrison Formation, Jurassic, Corresponding author Cranial anatomy Mark A. -

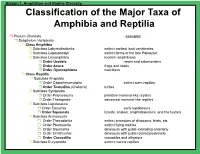

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are