XX Век II. METAETHICS of the 20Th CENTUR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Hume and the Origin of Modern Rationalism Donald Livingston Emory University

A Symposium: Morality Reconsidered David Hume and the Origin of Modern Rationalism Donald Livingston Emory University In “How Desperate Should We Be?” Claes Ryn argues that “morality” in modern societies is generally understood to be a form of moral rationalism, a matter of applying preconceived moral principles to particular situations in much the same way one talks of “pure” and “applied” geometry. Ryn finds a num- ber of pernicious consequences to follow from this rationalist model of morals. First, the purity of the principles, untainted by the particularities of tradition, creates a great distance between what the principles demand and what is possible in actual experience. The iridescent beauty and demands of the moral ideal distract the mind from what is before experience.1 The practical barriers to idealistically demanded change are oc- cluded from perception, and what realistically can and ought to be done is dismissed as insufficient. And “moral indignation is deemed sufficient”2 to carry the day in disputes over policy. Further, the destruction wrought by misplaced idealistic change is not acknowledged to be the result of bad policy but is ascribed to insufficient effort or to wicked persons or groups who have derailed it. A special point Ryn wants to make is that, “One of the dangers of moral rationalism and idealism is DONAL D LIVINGSTON is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Emory Univer- sity. 1 Claes Ryn, “How Desperate Should We Be?” Humanitas, Vol. XXVIII, Nos. 1 & 2 (2015), 9. 2 Ibid., 18. 44 • Volume XXVIII, Nos. 1 and 2, 2015 Donald Livingston that they set human beings up for desperation. -

Generic Statements and Antirealism

GENERIC STATEMENTS AND ANTIREALISM Panayot BUTCHVAROV ABSTRACT: The standard arguments for antirealism are densely abstract, often enigmatic, and thus unpersuasive. The ubiquity and irreducibility of what linguists call generic statements provides a clear argument from a specific and readily understandable case. We think and talk about the world as necessarily subject to generalization. But the chief vehicles of generalization are generic statements, typically of the form “Fs are G,” not universal statements, typically of the form “All Fs are G.” Universal statements themselves are usually intended and understood as though they were only generic. Even if there are universal facts, as Russell held, there are no generic facts. There is no genericity in the world as it is “in-itself.” There is genericity in it only as it is “for-us.” KEYWORDS: Generic, General, Antirealism I shall take general statements to include those that logicians call universal, typically of the form “All Fs are G,” and particular, of the form “Some Fs are G,” but also those that linguists call generic, typically of the form “Fs are G.” The term ‘realism’ will be used for the metaphysical view that reality, the ‘world,’ is mind- independent, in particular, independent of our knowledge of it. ‘Antirealism’ will stand for the opposite view, including Kant’s transcendental idealism as well as recent positions such as Michael Dummett’s ‘antirealism,’ Nelson Goodman’s ‘irrealism,’ and Hilary Putnam’s ‘internal realism.’ According to antirealism, reality depends, insofar as it is known or knowable, on our ways of knowing it, our cognitive capacities – sense perception, introspection, intellectual intuition, imagination, memory, recognition, conceptualization, inductive and deductive reasoning, use of language and other symbolism. -

Other Moral Theories : Subjectivism, Relativism, Emotivism, Intuitionism, Etc

INTRODUCTION TO ETHICS 30 Other Moral Theories: Subjectivism, Relativism, Emotivism, Intuitionism, etc. 1 Jan Franciszek Jacko Metaethics includes moral theories that contain assumptions which answer some metaphysical and epistemological questions about moral goods and values. The metaphysical questions (such as What are, and how do moral goods and values exist?) are about the nature and existence of moral goods and values. Epistemological questions (such as Can we know moral goods and values? If so, what are the sources of knowledge about them?) regard sources of knowledge about moral goods, values and criteria of moral evaluations.2 Assumptions of ethical subjectivism, relativism, decisionism, emotivism and intuitionism are exemplary answers to these questions. We call their answers “normative assumptions.” There are at least three good reasons to ask and answer such questions. First, without answering them, moral judgments remain ambiguous. For example, if I say, “Action X is wrong,” the judgement has several meanings. To specify its sense, I should clarify my normative assumptions. For example, I can assume metaphysical subjectivism (anti-realism) or realism in metaethics. According to the former assumption, my above judgment about X is not about reality; it is about my or someone’s opinion. In this case, the exact meaning of this judgement is: someone evaluates X as morally wrong. If I assume the counter-assumption of metaphysical realism (anti-subjectivism), I mean that it is true that X has the property of moral wrongness. Second, these assumptions are conductive to peculiar practices. To specify the practice, which follows from moral judgments, one has to determine some normative assumptions. -

Moral Implications of Darwinian Evolution for Human Reference

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2006 Moral Implications of Darwinian Evolution for Human Reference Based in Christian Ethics: a Critical Analysis and Response to the "Moral Individualism" of James Rachels Stephen Bauer Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christianity Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Evolution Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Bauer, Stephen, "Moral Implications of Darwinian Evolution for Human Reference Based in Christian Ethics: a Critical Analysis and Response to the "Moral Individualism" of James Rachels" (2006). Dissertations. 16. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/16 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary MORAL IMPLICATIONS OF DARWINIAN EVOLUTION FOR HUMAN PREFERENCE BASED IN CHRISTIAN ETHICS: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS AND RESPONSE TO THE “MORAL INDIVIDUALISM” OF JAMES RACHELS A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Stephen Bauer November 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3248152 Copyright 2006 by Bauer, Stephen All rights reserved. -

Sellars in Context: an Analysis of Wilfrid Sellars's Early Works Peter Jackson Olen University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Sellars in Context: An Analysis of Wilfrid Sellars's Early Works Peter Jackson Olen University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Olen, Peter Jackson, "Sellars in Context: An Analysis of Wilfrid Sellars's Early Works" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4191 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sellars in Context: An Analysis of Wilfrid Sellars’s Early Works by Peter Olen A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Stephen Turner, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Richard Manning, Ph.D. Rebecca Kukla, Ph.D. Alexander Levine, Ph.D. Willem deVries, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 20th, 2012 Keywords: Logical Positivism, History of Analytic Philosophy Copyright © 2012, Peter Olen DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to the faculty members and fellow graduate students who helped me along the way. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank Rebecca Kukla, Richard Manning, Stephen Turner, Willem deVries, Alex Levine, Roger Ariew, Eric Winsberg, Charles Guigon, Nancy Stanlick, Michael Strawser, and the myriad of faculty members who were instrumental in getting me to this point. -

Counterfactuals and Antirealism

ISSN 2664-4002 (Print) & ISSN 2664-6714 (Online) South Asian Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: South Asian Res J Human Soc Sci | Volume-1 | Issue-1| Jun-Jul -2019 | Short Communication Counterfactuals and Antirealism Panayot Butchvarov* The University of Iowa USA *Corresponding Author Panayot Butchvarov Article History Received: 12.07.2019 Accepted: 24.07.2019 Published: 30.07.2019 Abstract: There could be no causal connections in the world because if there were there would be counterfactual facts, and there are no such facts. Cognition of the world must employ counterfactual statements, roughly of the form “If p were true, then q would be true,” but obviously there are no counterfactual facts. Keywords: cognition, antirealism, causality, counterfactual The ways to antirealism Metaphysical antirealism is seemingly incredible but, paradoxically, also self-evident. It seems self-evident insofar as it says that if there is a world that we do not and cannot cognize (Kant‟s “things-in-themselves”) then we can ignore it, and if there is a world that we do or at least can cognize (Kant‟s “things-for-us”) then it can only be the world as we do or can cognize it. So the world we do cognize seems, in a sense, dependent on our cognition of it. (We may think of cognition as the capacity for knowledge, and of knowledge as the successful exercise of that capacity.) Metaphysical antirealism is not solipsistic – it‟s about what we, not what I, do or can cognize. For cognition of a world, unlike cognition of a toothache but like cognition of physics, mathematics, geography, or history, is inseparable from others‟ cognition – from the common language we speak to most of the views we espouse. -

MORAL OBJECTIVITY and the PSYCHOLOGY of MOTIVATION by Jude Ndubuisi Edeh a DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfilment Of

Philosophy MORAL OBJECTIVITY AND THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MOTIVATION By Jude Ndubuisi Edeh A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Dr.phil) University of Münster Münster, Germany 2017 Dekan:Prof. Dr. Thomas Großbölting Erstgutachter: PD. Dr. Michael Kühler Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Reinold Schmücker Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 04.10.2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am immensely grateful to Michael Kühler and Reinold Schmücker, my supervisors, for their generosity with their time, energy and support. It’s not always a given that you find people who are both interested in your project and believe you can handle it, especially at its budding stage. I benefited tremendously from your constructive criticisms and helpful comments, without which the completion of this project would not have been successful. I owe, in addition, a significant debt of gratitude to Nadine Elzein for supervising this project during my research stay at the King’s College, University of London. Nadine, your enthusiasm, philosophical insight and suggestions are invaluable. I owe special thanks also to Lukas Meyer for hosting me in August 2015 at the Institute of Philosophy, University of Graz. This project would not have been possible without the friendship, support, and insight of a good many people. In particular, I owe a significant debt of gratitude to: Nnaemeka’s family, Anthony Anih’s family, Anthony C. Ajah, Uzoma Emenogu, Vitus Egwu. I will always remain indebted to my family for their undying care and love. I would never have made it this far without your encouragement and support. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation provides a solution to the tension of specifying and reconciling the relationship between moral judgement and motivation. -

An Introduction to Philosophy

An Introduction to Philosophy W. Russ Payne Bellevue College Copyright (cc by nc 4.0) 2015 W. Russ Payne Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document with attribution under the terms of Creative Commons: Attribution Noncommercial 4.0 International or any later version of this license. A copy of the license is found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 1 Contents Introduction ………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 1: What Philosophy Is ………………………….. 5 Chapter 2: How to do Philosophy ………………….……. 11 Chapter 3: Ancient Philosophy ………………….………. 23 Chapter 4: Rationalism ………….………………….……. 38 Chapter 5: Empiricism …………………………………… 50 Chapter 6: Philosophy of Science ………………….…..… 58 Chapter 7: Philosophy of Mind …………………….……. 72 Chapter 8: Love and Happiness …………………….……. 79 Chapter 9: Meta Ethics …………………………………… 94 Chapter 10: Right Action ……………………...…………. 108 Chapter 11: Social Justice …………………………...…… 120 2 Introduction The goal of this text is to present philosophy to newcomers as a living discipline with historical roots. While a few early chapters are historically organized, my goal in the historical chapters is to trace a developmental progression of thought that introduces basic philosophical methods and frames issues that remain relevant today. Later chapters are topically organized. These include philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, areas where philosophy has shown dramatic recent progress. This text concludes with four chapters on ethics, broadly construed. I cover traditional theories of right action in the third of these. Students are first invited first to think about what is good for themselves and their relationships in a chapter of love and happiness. Next a few meta-ethical issues are considered; namely, whether they are moral truths and if so what makes them so. -

Ethical Realism/Moral Realism Ethical Propositions That Refer to Objective Features May Be True If They Are Free of Subjectivis

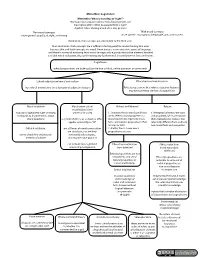

Metaethics: Cognitivism Metaethics: What is morality, or “right”? Normative (prescriptive) ethics: How should people act? Descriptive ethics: What do people think is right? Applied ethics: Putting moral ideas into practice Thin moral concepts Thick moral concepts more general: good, bad, right, and wrong more specic: courageous, inequitable, just, or dishonest Centralism- thin concepts are antecedent to the thick ones Non-centralism- thick concepts are a sucient starting point for understanding thin ones because thin and thick concepts are equal. Normativity is a non-excisable aspect of language and there is no way of analyzing thick moral concepts into a purely descriptive element attached to a thin moral evaluation, thus undermining any fundamental division between facts and norms. Cognitivism ethical propositions are truth-apt (can be true or false), unlike questions or commands Ethical subjectivism/moral anti-realism Ethical realism/moral realism True ethical propositions are a function of subjective features Ethical propositions that refer to objective features may be true if they are free of subjectivism Moral relativism Moral universalism/ Robust and Minimal Robust moral objectivism/ nobody is objectively right or wrong universal morality 1. Semantic thesis: moral predicates 3. Metaphysical thesis: the facts in regards to diagreements about are to refer to moral properties so and properties of #1 are robust-- moral questions a system of ethics, or a universal ethic, moral statements represent moral their metaphysical status is not applies universally to "all" facts, and express propositions that relevantly dierent from ordinary are true or false non-moral facts and properties Cultural relativism not all forms of moral universalism 2. -

T H E O B S E R V

o cr The Observer 1 8 4 2 -1 9 9 2 @----------- SE SOUlCENTt NNIAl T he O bserver Saint MarvS College NOTRE DAME - INDIANA VOL XXIV NO. 117 Wednesday, March 25, 1992 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY’S S. Korean governing party concedes defeat SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — told jubilant supporters. President Roh Tae-woo’s con With more than 90 percent of servative party acknowledged the votes counted for National Wednesday that it suffered a Assembly elections, the Demo surprise defeat in South Korea’s cratic Liberals led in 113 of the general elections and failed to 237 single-member districts, six retain majority control of seats short of a majority, KBS parliament. Television said. The election reflected strains To form a government, Rob’s in the government’s traditional party is likely to try to merge alliance with big business, with an opposition group or en which has been resisting efforts tice independent candidates to increase public control over into its fold, as it did after the one of the world’s fastest- last general election, in 1988. growing economies. The powerful founder of The results indicated lower Hyundai, who formed a party than expected support for the just one month ago and cam ruling party as it prepares for paigned to stop government the presidential election this fall meddling in business, won 24 to replace Roh, whose single seats. five-year term ends next “We watched the election re February. sults with shock and disap pointment, but we will humbly Candidates of the main oppo accept the people’s will,” said sition group led in 77 districts Kim Yoon-hwan, secretary gen and a month-old party founded eral of the ruling Democratic by maverick millionaire Chung Liberal Party. -

The Practical Turn' David G

8 The Practical Turn' David G. Stern What is Practice Theory? What is a Practice? What is "practice theory"? The best short answer is that it is any theory that treats practice as a fundamental category, or takes practices as its point of departure . Naturally, this answer leads to further questions . What is meant by "practices" here? What is involved in taking practices as a point of departure or a fundamental category, and what does that commitment amount to? And what is the point of the contrast between a practice-based theory and one that starts elsewhere? Perhaps the most significant point of agreement among those who have taken the practical turn is that it offers a way out of Procustean yet seemingly inescap- able categories, such as subject and object, representation and represented, con- ceptual scheme and content, belief and desire, structure and action, rules and their application, micro and macro, individual and totality . Instead, practice the- orists propose that we start with practices and rethink our theories from the ground up. Bourdieu, for instance, insists that only a theory of practice can open up a way forward : Objective analysis of practical apprehension of the familiar world . teaches us that we shall escape from the ritual either/or choice between objectivism and subjectiv- ism in which the social sciences have so far allowed themselves to be trapped only if we are prepared to inquire into the mode of production and functioning of the practical mastery which makes possible both an objectively intelligible practice and also an objectively enchanted experience of that practice . -

December 2001

MARCIA BARON CURRICULUM VITAE January 2020 Department of Philosophy Sycamore Hall 026 Indiana University 1033 E. 3rd St. Bloomington, IN 47405 Education: University of North Carolina Ph.D. (Philosophy) 1982 M.A. (Philosophy) 1978 Oberlin College B.A. with high honors (Majors: Philosophy and Spanish) 1976 Professional Positions: Honorary Professor, University of St. Andrews 2014-2017 Professor, University of St. Andrews 2012-2014 Rudy Professor, Indiana University, Bloomington 2004- Professor, Indiana University, Bloomington 2001- Visiting Scholar, Dartmouth College Summers 2005 and 2007 Visiting Professor, University of Auckland (New Zealand) Summer 1999 Professor, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign 1996-2001 Visiting Research Fellow, University of Melbourne (Australia) Summer 1995 Associate Professor, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign 1989-96 Visiting Associate Professor, University of Chicago Spring 1990 Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Michigan Spring 1987 Visiting Assistant Professor, Stanford University Spring 1985 Assistant Professor, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign 1983-89 Visiting Assistant Professor, UIUC 1982-83 Assistant Professor, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University 1982-83 Instructor, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University 1981-82 Instructor, Illinois State University Spring 1980 Areas of Specialization: Ethics, Philosophy of Criminal Law Area of Competence: History of Ethics, Political Philosophy, Philosophical Issues in Feminism Academic Awards and Honors: Short-term faculty exchange award from IU with University of Bayreuth for June-July, 2019 Erasmus Program Guest Professorship, University of Pavia, Italy, March 2013 Awarded a year-long NEH fellowship for 2010 Awarded one semester of release time from College Arts and Humanities Institute (CAHI), Indiana University, for Fall 2009 Joseph Rodman Visiting Professorship, University of Western Ontario, October 2005 President, Central Division of the American Philosophical Association, 2002-2003 Vice-President, 2001-2002.