Serum Response Factor Controls Transcriptional Network Regulating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Propranolol-Mediated Attenuation of MMP-9 Excretion in Infants with Hemangiomas

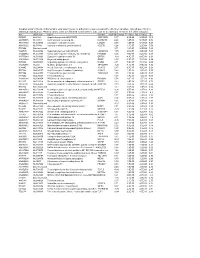

Supplementary Online Content Thaivalappil S, Bauman N, Saieg A, Movius E, Brown KJ, Preciado D. Propranolol-mediated attenuation of MMP-9 excretion in infants with hemangiomas. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4773 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/01/2021 eTable. List of All of the Proteins Identified by Proteomics Protein Name Prop 12 mo/4 Pred 12 mo/4 Δ Prop to Pred mo mo Myeloperoxidase OS=Homo sapiens GN=MPO 26.00 143.00 ‐117.00 Lactotransferrin OS=Homo sapiens GN=LTF 114.00 205.50 ‐91.50 Matrix metalloproteinase‐9 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MMP9 5.00 36.00 ‐31.00 Neutrophil elastase OS=Homo sapiens GN=ELANE 24.00 48.00 ‐24.00 Bleomycin hydrolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=BLMH 3.00 25.00 ‐22.00 CAP7_HUMAN Azurocidin OS=Homo sapiens GN=AZU1 PE=1 SV=3 4.00 26.00 ‐22.00 S10A8_HUMAN Protein S100‐A8 OS=Homo sapiens GN=S100A8 PE=1 14.67 30.50 ‐15.83 SV=1 IL1F9_HUMAN Interleukin‐1 family member 9 OS=Homo sapiens 1.00 15.00 ‐14.00 GN=IL1F9 PE=1 SV=1 MUC5B_HUMAN Mucin‐5B OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC5B PE=1 SV=3 2.00 14.00 ‐12.00 MUC4_HUMAN Mucin‐4 OS=Homo sapiens GN=MUC4 PE=1 SV=3 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 HRG_HUMAN Histidine‐rich glycoprotein OS=Homo sapiens GN=HRG 1.00 12.00 ‐11.00 PE=1 SV=1 TKT_HUMAN Transketolase OS=Homo sapiens GN=TKT PE=1 SV=3 17.00 28.00 ‐11.00 CATG_HUMAN Cathepsin G OS=Homo -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Supplementary File 2A Revised

Supplementary file 2A. Differentially expressed genes in aldosteronomas compared to all other samples, ranked according to statistical significance. Missing values were not allowed in aldosteronomas, but to a maximum of five in the other samples. Acc UGCluster Name Symbol log Fold Change P - Value Adj. P-Value B R99527 Hs.8162 Hypothetical protein MGC39372 MGC39372 2,17 6,3E-09 5,1E-05 10,2 AA398335 Hs.10414 Kelch domain containing 8A KLHDC8A 2,26 1,2E-08 5,1E-05 9,56 AA441933 Hs.519075 Leiomodin 1 (smooth muscle) LMOD1 2,33 1,3E-08 5,1E-05 9,54 AA630120 Hs.78781 Vascular endothelial growth factor B VEGFB 1,24 1,1E-07 2,9E-04 7,59 R07846 Data not found 3,71 1,2E-07 2,9E-04 7,49 W92795 Hs.434386 Hypothetical protein LOC201229 LOC201229 1,55 2,0E-07 4,0E-04 7,03 AA454564 Hs.323396 Family with sequence similarity 54, member B FAM54B 1,25 3,0E-07 5,2E-04 6,65 AA775249 Hs.513633 G protein-coupled receptor 56 GPR56 -1,63 4,3E-07 6,4E-04 6,33 AA012822 Hs.713814 Oxysterol bining protein OSBP 1,35 5,3E-07 7,1E-04 6,14 R45592 Hs.655271 Regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis 2 RIMS2 2,51 5,9E-07 7,1E-04 6,04 AA282936 Hs.240 M-phase phosphoprotein 1 MPHOSPH -1,40 8,1E-07 8,9E-04 5,74 N34945 Hs.234898 Acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase beta ACACB 0,87 9,7E-07 9,8E-04 5,58 R07322 Hs.464137 Acyl-Coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl ACOX1 0,82 1,3E-06 1,2E-03 5,35 R77144 Hs.488835 Transmembrane protein 120A TMEM120A 1,55 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,07 H68542 Hs.420009 Transcribed locus 1,07 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,06 AA410184 Hs.696454 PBX/knotted 1 homeobox 2 PKNOX2 1,78 2,0E-06 -

The Correlation of Keratin Expression with In-Vitro Epithelial Cell Line Differentiation

The correlation of keratin expression with in-vitro epithelial cell line differentiation Deeqo Aden Thesis submitted to the University of London for Degree of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) Supervisors: Professor Ian. C. Mackenzie Professor Farida Fortune Centre for Clinical and Diagnostic Oral Science Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry Queen Mary, University of London 2009 Contents Content pages ……………………………………………………………………......2 Abstract………………………………………………………………………….........6 Acknowledgements and Declaration……………………………………………...…7 List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………8 List of Tables………………………………………………………………………...12 Abbreviations….………………………………………………………………..…...14 Chapter 1: Literature review 16 1.1 Structure and function of the Oral Mucosa……………..…………….…..............17 1.2 Maintenance of the oral cavity...……………………………………….................20 1.2.1 Environmental Factors which damage the Oral Mucosa………. ….…………..21 1.3 Structure and function of the Oral Mucosa ………………...….……….………...21 1.3.1 Skin Barrier Formation………………………………………………….……...22 1.4 Comparison of Oral Mucosa and Skin…………………………………….……...24 1.5 Developmental and Experimental Models used in Oral mucosa and Skin...……..28 1.6 Keratinocytes…………………………………………………….….....................29 1.6.1 Desmosomes…………………………………………….…...............................29 1.6.2 Hemidesmosomes……………………………………….…...............................30 1.6.3 Tight Junctions………………………….……………….…...............................32 1.6.4 Gap Junctions………………………….……………….….................................32 -

MALE Protein Name Accession Number Molecular Weight CP1 CP2 H1 H2 PDAC1 PDAC2 CP Mean H Mean PDAC Mean T-Test PDAC Vs. H T-Test

MALE t-test t-test Accession Molecular H PDAC PDAC vs. PDAC vs. Protein Name Number Weight CP1 CP2 H1 H2 PDAC1 PDAC2 CP Mean Mean Mean H CP PDAC/H PDAC/CP - 22 kDa protein IPI00219910 22 kDa 7 5 4 8 1 0 6 6 1 0.1126 0.0456 0.1 0.1 - Cold agglutinin FS-1 L-chain (Fragment) IPI00827773 12 kDa 32 39 34 26 53 57 36 30 55 0.0309 0.0388 1.8 1.5 - HRV Fab 027-VL (Fragment) IPI00827643 12 kDa 4 6 0 0 0 0 5 0 0 - 0.0574 - 0.0 - REV25-2 (Fragment) IPI00816794 15 kDa 8 12 5 7 8 9 10 6 8 0.2225 0.3844 1.3 0.8 A1BG Alpha-1B-glycoprotein precursor IPI00022895 54 kDa 115 109 106 112 111 100 112 109 105 0.6497 0.4138 1.0 0.9 A2M Alpha-2-macroglobulin precursor IPI00478003 163 kDa 62 63 86 72 14 18 63 79 16 0.0120 0.0019 0.2 0.3 ABCB1 Multidrug resistance protein 1 IPI00027481 141 kDa 41 46 23 26 52 64 43 25 58 0.0355 0.1660 2.4 1.3 ABHD14B Isoform 1 of Abhydrolase domain-containing proteinIPI00063827 14B 22 kDa 19 15 19 17 15 9 17 18 12 0.2502 0.3306 0.7 0.7 ABP1 Isoform 1 of Amiloride-sensitive amine oxidase [copper-containing]IPI00020982 precursor85 kDa 1 5 8 8 0 0 3 8 0 0.0001 0.2445 0.0 0.0 ACAN aggrecan isoform 2 precursor IPI00027377 250 kDa 38 30 17 28 34 24 34 22 29 0.4877 0.5109 1.3 0.8 ACE Isoform Somatic-1 of Angiotensin-converting enzyme, somaticIPI00437751 isoform precursor150 kDa 48 34 67 56 28 38 41 61 33 0.0600 0.4301 0.5 0.8 ACE2 Isoform 1 of Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 precursorIPI00465187 92 kDa 11 16 20 30 4 5 13 25 5 0.0557 0.0847 0.2 0.4 ACO1 Cytoplasmic aconitate hydratase IPI00008485 98 kDa 2 2 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 - 0.0081 - 0.0 -

Downloaded 18 July 2014 with a 1% False Discovery Rate (FDR)

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Chemical glycoproteomics for identification and discovery of glycoprotein alterations in human cancer Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0t47b9ws Author Spiciarich, David Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Chemical glycoproteomics for identification and discovery of glycoprotein alterations in human cancer by David Spiciarich A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Co-Chair Professor David E. Wemmer, Co-Chair Professor Matthew B. Francis Professor Amy E. Herr Fall 2017 Chemical glycoproteomics for identification and discovery of glycoprotein alterations in human cancer © 2017 by David Spiciarich Abstract Chemical glycoproteomics for identification and discovery of glycoprotein alterations in human cancer by David Spiciarich Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry University of California, Berkeley Professor Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Co-Chair Professor David E. Wemmer, Co-Chair Changes in glycosylation have long been appreciated to be part of the cancer phenotype; sialylated glycans are found at elevated levels on many types of cancer and have been implicated in disease progression. However, the specific glycoproteins that contribute to cell surface sialylation are not well characterized, specifically in bona fide human cancer. Metabolic and bioorthogonal labeling methods have previously enabled enrichment and identification of sialoglycoproteins from cultured cells and model organisms. The goal of this work was to develop technologies that can be used for detecting changes in glycoproteins in clinical models of human cancer. -

Strand Breaks for P53 Exon 6 and 8 Among Different Time Course of Folate Depletion Or Repletion in the Rectosigmoid Mucosa

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE COLON p53 EXONIC STRAND BREAKS DURING FOLATE DEPLETION-REPLETION INTERVENTION Supplemental Figure Legend Strand breaks for p53 exon 6 and 8 among different time course of folate depletion or repletion in the rectosigmoid mucosa. The input of DNA was controlled by GAPDH. The data is shown as ΔCt after normalized to GAPDH. The higher ΔCt the more strand breaks. The P value is shown in the figure. SUPPLEMENT S1 Genes that were significantly UPREGULATED after folate intervention (by unadjusted paired t-test), list is sorted by P value Gene Symbol Nucleotide P VALUE Description OLFM4 NM_006418 0.0000 Homo sapiens differentially expressed in hematopoietic lineages (GW112) mRNA. FMR1NB NM_152578 0.0000 Homo sapiens hypothetical protein FLJ25736 (FLJ25736) mRNA. IFI6 NM_002038 0.0001 Homo sapiens interferon alpha-inducible protein (clone IFI-6-16) (G1P3) transcript variant 1 mRNA. Homo sapiens UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 15 GALNTL5 NM_145292 0.0001 (GALNT15) mRNA. STIM2 NM_020860 0.0001 Homo sapiens stromal interaction molecule 2 (STIM2) mRNA. ZNF645 NM_152577 0.0002 Homo sapiens hypothetical protein FLJ25735 (FLJ25735) mRNA. ATP12A NM_001676 0.0002 Homo sapiens ATPase H+/K+ transporting nongastric alpha polypeptide (ATP12A) mRNA. U1SNRNPBP NM_007020 0.0003 Homo sapiens U1-snRNP binding protein homolog (U1SNRNPBP) transcript variant 1 mRNA. RNF125 NM_017831 0.0004 Homo sapiens ring finger protein 125 (RNF125) mRNA. FMNL1 NM_005892 0.0004 Homo sapiens formin-like (FMNL) mRNA. ISG15 NM_005101 0.0005 Homo sapiens interferon alpha-inducible protein (clone IFI-15K) (G1P2) mRNA. SLC6A14 NM_007231 0.0005 Homo sapiens solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter) member 14 (SLC6A14) mRNA. -

University of California, San Diego

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The post-terminal differentiation fate of RNAs revealed by next-generation sequencing Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7324r1rj Author Lefkowitz, Gloria Kuo Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The post-terminal differentiation fate of RNAs revealed by next-generation sequencing A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Sciences by Gloria Kuo Lefkowitz Committee in Charge: Professor Benjamin D. Yu, Chair Professor Richard Gallo Professor Bruce A. Hamilton Professor Miles F. Wilkinson Professor Eugene Yeo 2012 Copyright Gloria Kuo Lefkowitz, 2012 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Gloria Kuo Lefkowitz is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii DEDICATION Ma and Ba, for your early indulgence and support. Matt and James, for choosing more practical callings. Roy, my love, for patiently sharing the ups and downs -

Types I and II Keratin Intermediate Filaments

Downloaded from http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/ on October 10, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Types I and II Keratin Intermediate Filaments Justin T. Jacob,1 Pierre A. Coulombe,1,2 Raymond Kwan,3 and M. Bishr Omary3,4 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21205 2Departments of Biological Chemistry, Dermatology, and Oncology, School of Medicine, and Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21205 3Departments of Molecular & Integrative Physiologyand Medicine, Universityof Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 4VA Ann Arbor Health Care System, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48105 Correspondence: [email protected] SUMMARY Keratins—types I and II—are the intermediate-filament-forming proteins expressed in epithe- lial cells. They are encoded by 54 evolutionarily conserved genes (28 type I, 26 type II) and regulated in a pairwise and tissue type–, differentiation-, and context-dependent manner. Here, we review how keratins serve multiple homeostatic and stress-triggered mechanical and nonmechanical functions, including maintenance of cellular integrity, regulation of cell growth and migration, and protection from apoptosis. These functions are tightly regulated by posttranslational modifications and keratin-associated proteins. Genetically determined alterations in keratin-coding sequences underlie highly penetrant and rare disorders whose pathophysiology reflects cell fragility or altered -

In Silico Analysis of Gene Expression Data from Bald Frontal and Haired Occipital Scalp to Identify Candidate Genes in Male Androgenetic Alopecia

Archives of Dermatological Research (2019) 311:815–824 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-019-01973-2 ORIGINAL PAPER In silico analysis of gene expression data from bald frontal and haired occipital scalp to identify candidate genes in male androgenetic alopecia A. Premanand1 · B. Reena Rajkumari1 Received: 5 September 2018 / Revised: 6 July 2019 / Accepted: 30 August 2019 / Published online: 11 September 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is a progressive dermatological disorder of frontal and vertex scalp hair loss leading to bald- ness in men. This study aimed to identify candidate genes involved in AGA through an in silico search strategy. The gene expression profle GS36169, which contains microarray gene expression data from bald frontal and haired occipital scalps of fve men with AGA, was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. The diferential gene expression analysis for all fve subjects was carried out separately by PUMA package in R and identifed 32 diferentially expressed genes (DEGs) common to all fve subjects. Gene ontology (GO) biological process and pathway- enrichment analyses of the DEGs were conducted separately for the up-regulated and down-regulated genes. ReactomeFIViz app was utilized to construct the protein functional interaction network for the DEGs. Through GO biological process and pathway analysis on the clusters of the Reactome FI network, we found that the down-regulated DEGs participate in Wnt signaling, TGF-beta signaling, -

The Hypothalamus As a Hub for SARS-Cov-2 Brain Infection and Pathogenesis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139329; this version posted June 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The hypothalamus as a hub for SARS-CoV-2 brain infection and pathogenesis Sreekala Nampoothiri1,2#, Florent Sauve1,2#, Gaëtan Ternier1,2ƒ, Daniela Fernandois1,2 ƒ, Caio Coelho1,2, Monica ImBernon1,2, Eleonora Deligia1,2, Romain PerBet1, Vincent Florent1,2,3, Marc Baroncini1,2, Florence Pasquier1,4, François Trottein5, Claude-Alain Maurage1,2, Virginie Mattot1,2‡, Paolo GiacoBini1,2‡, S. Rasika1,2‡*, Vincent Prevot1,2‡* 1 Univ. Lille, Inserm, CHU Lille, Lille Neuroscience & Cognition, DistAlz, UMR-S 1172, Lille, France 2 LaBoratorY of Development and PlasticitY of the Neuroendocrine Brain, FHU 1000 daYs for health, EGID, School of Medicine, Lille, France 3 Nutrition, Arras General Hospital, Arras, France 4 Centre mémoire ressources et recherche, CHU Lille, LiCEND, Lille, France 5 Univ. Lille, CNRS, INSERM, CHU Lille, Institut Pasteur de Lille, U1019 - UMR 8204 - CIIL - Center for Infection and ImmunitY of Lille (CIIL), Lille, France. # and ƒ These authors contriButed equallY to this work. ‡ These authors directed this work *Correspondence to: [email protected] and [email protected] Short title: Covid-19: the hypothalamic hypothesis 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139329; this version posted June 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Supplemental Figures

1 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS: 2 3 Supplemental figures 4 1 Control lung IPF lung (perivascular space) (fbroblast foci) PRRX1 PRRX1 PRRX1 PRRX1 aB VIM b ACTA2 d VIM e ACTA2 PRRX1 PRRX1 c CD45 f CD45 Supplemental Figure 1 5 Supplemental Figure S1: Co-expression of PRRX1 with Vimentin and ACTA2 in control 6 and IPF lungs by immunochemistry. 7 (a-c) Representative immunohistochemistry images (n=3 per group) in control lung showing 8 PRRX1 staining (Brown Chromogen, nuclear staining) in perivascular space with (a) Vimentin 9 (Red chromogen), (b) ACTA2 (Red chromogen) and (c) CD45 (Red chromogen). Note that 10 PRRX1 positive cells (arrow) were Vimentine positive (a) but ACTA2 (b) and CD45 negative 11 (c). Insert in (a): high magnification of the black dashed box in the main left panel showing a 12 double positive PRRX1 (brown nuclear staining, outlined with dashed white line) and Vimentin 13 (red cytoplasmic staining) cell. Insert in (c): high magnification of the black dashed box in the 14 main bottom panel showing a PRRX1 (brown nuclear staining) positive but CD45 negative cell 15 (arrow) as well as a CD45 (red cytoplasmic staining) positive but PRRX1 negative cell 16 (arrowhead). (d-f) Representative immunohistochemistry images (n=3 per group) showing 17 PRRX1 staining (Brown Chromogen, nuclear staining) in IPF fibroblast foci with (d) Vimentin 18 (Red chromogen), (e) ACTA2 (Red chromogen) and (f) CD45 (Red chromogen). Note that 19 PRRX1 positive cells were Vimentin positive (see black arrow in (d)) but only some were 20 ACTA2 positive (arrow and dashed box in (e)). PRRX1pos ACTA2neg cells were also present 21 (see arrowhead in (e)).