On the Neurobiology of Physical Activity in Mice and Human in Search of Eating Disorders Determinants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bacillus Anthracis Edema Factor Substrate Specificity: Evidence for New Modes of Action

Toxins 2012, 4, 505-535; doi:10.3390/toxins4070505 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072–6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Review Bacillus anthracis Edema Factor Substrate Specificity: Evidence for New Modes of Action Martin Göttle 1,*, Stefan Dove 2 and Roland Seifert 3 1 Department of Neurology, Emory University School of Medicine, 6302 Woodruff Memorial Research Building, 101 Woodruff Circle, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA 2 Department of Medicinal/Pharmaceutical Chemistry II, University of Regensburg, D-93040 Regensburg, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Institute of Pharmacology, Medical School of Hannover, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, D-30625 Hannover, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-404-727-1678; Fax: +1-404-727-3157. Received: 23 April 2012; in revised form: 15 June 2012 / Accepted: 27 June 2012 / Published: 6 July 2012 Abstract: Since the isolation of Bacillus anthracis exotoxins in the 1960s, the detrimental activity of edema factor (EF) was considered as adenylyl cyclase activity only. Yet the catalytic site of EF was recently shown to accomplish cyclization of cytidine 5′-triphosphate, uridine 5′-triphosphate and inosine 5′-triphosphate, in addition to adenosine 5′-triphosphate. This review discusses the broad EF substrate specificity and possible implications of intracellular accumulation of cyclic cytidine 3′:5′-monophosphate, cyclic uridine 3′:5′-monophosphate and cyclic inosine 3′:5′-monophosphate on cellular functions vital for host defense. In particular, cAMP-independent mechanisms of action of EF on host cell signaling via protein kinase A, protein kinase G, phosphodiesterases and CNG channels are discussed. -

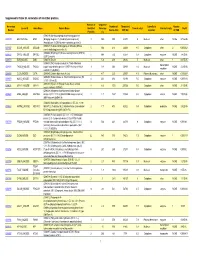

Supporting Table S3 for PDF Maker

Supplemental Table S3. Annotation of identified proteins. Number of Sequence Accession Number of Theoretical Subcellular Number Locus ID Gene Name Protein Name Identified Coverage Theoretical pI Protein Family NSAF Number Amino Acid MW (Da) Location of TMD Peptides (%) (O08539) Myc box-dependent-interacting protein 1 O08539 BIN1_MOUSE BIN1 (Bridging integrator 1) (Amphiphysin-like protein) 3 10.5 588 64470 5 Nucleus other NONE 5.73E-05 (Amphiphysin II) (SH3-domain-containing protein 9) (O08547) Vesicle-trafficking protein SEC22b (SEC22 O08547 SC22B_MOUSE SEC22B 5 30.4 214 24609 8.5 Cytoplasm other 2 0.000262 vesicle-trafficking protein-like 1) (O08553) Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 (DRP-2) O08553 DPYL2_MOUSE DPYSL2 5 19.4 572 62278 6.4 Cytoplasm enzyme NONE 7.85E-05 (ULIP 2 protein) O08579 EMD_MOUSE EMD (O08579) Emerin 1 5.8 259 29436 5 Nucleus other 1 8.67E-05 (O08583) THO complex subunit 4 (Tho4) (RNA and transcription O08583 THOC4_MOUSE THOC4 export factor-binding protein 1) (REF1-I) (Ally of AML-1 1 9.8 254 26809 11.2 Nucleus NONE 2.21E-05 regulator and LEF-1) (Aly/REF) O08585 CLCA_MOUSE CLTA (O08585) Clathrin light chain A (Lca) 2 4.7 235 25557 4.5 Plasma Membrane other NONE 0.000287 (O08600) Endonuclease G, mitochondrial precursor (EC O08600 NUCG_MOUSE ENDOG 4 23.1 294 32191 9.5 Cytoplasm enzyme NONE 0.000134 3.1.30.-) (Endo G) (O08638) Myosin-11 (Myosin heavy chain, smooth O08638 MYH11_MOUSE MYH11 8 6.6 1972 227026 5.5 Cytoplasm other NONE 3.13E-05 muscle isoform) (SMMHC) (O08648) Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase -

Dependent Protein Kinase to Cyclic CMP Agarose

Binding of Regulatory Subunits of Cyclic AMP- Dependent Protein Kinase to Cyclic CMP Agarose Andreas Hammerschmidt1., Bijon Chatterji2., Johannes Zeiser2, Anke Schro¨ der2, Hans- Gottfried Genieser3, Andreas Pich2, Volkhard Kaever1, Frank Schwede3, Sabine Wolter1", Roland Seifert1*" 1 Institute of Pharmacology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany, 2 Institute of Toxicology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany, 3 Biolog Life Science Institute, Bremen, Germany Abstract The bacterial adenylyl cyclase toxins CyaA from Bordetella pertussis and edema factor from Bacillus anthracis as well as soluble guanylyl cyclase a1b1 synthesize the cyclic pyrimidine nucleotide cCMP. These data raise the question to which effector proteins cCMP binds. Recently, we reported that cCMP activates the regulatory subunits RIa and RIIa of cAMP- dependent protein kinase. In this study, we used two cCMP agarose matrices as novel tools in combination with immunoblotting and mass spectrometry to identify cCMP-binding proteins. In agreement with our functional data, RIa and RIIa were identified as cCMP-binding proteins. These data corroborate the notion that cAMP-dependent protein kinase may serve as a cCMP target. Citation: Hammerschmidt A, Chatterji B, Zeiser J, Schro¨der A, Genieser H-G, et al. (2012) Binding of Regulatory Subunits of Cyclic AMP-Dependent Protein Kinase to Cyclic CMP Agarose. PLoS ONE 7(7): e39848. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039848 Editor: Andreas Hofmann, Griffith University, Australia Received May 11, 2012; Accepted May 31, 2012; Published July 9, 2012 Copyright: ß 2012 Hammerschmidt et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Mullergliaregnerationtranscriptome

gene.id fc1 fc2 fc3 fc4 p1 p2 p3 p4 FDR.pvalue-1 Gene Symbol Gene Title Pathway go biological process term go molecular function term go cellular component term Dr.10016.1.A1_at -2.33397 -3.86923 -4.38335 -2.39965 0.935201 0.320614 0.208 0.917227 0.208 zgc:77556 zgc:77556 --- proteolysis arylesterase activity /// metallopeptidase activity /// zinc ion --- binding Dr.10024.1.A1 at 1.483417 2.531269 2.089091 1.698761 1 0.613 0.998961 1 0.613 zgc:171808 zgc:171808--- cell-cell signaling --- --- Dr.10051.1.A1 at -1.78449 -2.22024 -1.70922 -1.99464 1 0.901663 1 0.999955 0.9017 ccng2 cyclin G2 --- --- --- --- Dr.10061.1.A1 at 2.065955 2.274632 2.248958 2.507754 0.992 0.718655 0.83 0.600609 0.6006 zgc:173506 zgc:173506--- --- --- --- Dr.10061.2.A1 at 2.131883 2.616483 2.49378 2.815337 0.983443 0.711513 0.805599 0.519115 0.5191 zgc:173506 Zgc:17350 --- --- --- --- Dr.10065.1.A1 at -1.02315 -2.01596 -2.29343 -1.88944 1 0.999955 0.957199 1 0.9572 zgc:114139 zgc:114139--- --- --- cytoplasm /// centrosome Dr.10070.1.A1_at -1.74365 -2.52206 -2.39093 -1.86817 1 0.741254 0.885401 1 0.7413 fbp1a fructose-1, --- carbohydrate metabolic process hydrolase activity /// phosphoric ester hydrolase activity --- Dr.10074.1.S1_at 6.035545 10.44051 7.880519 5.020371 0.1104 0.044 0.062491 0.144679 0.044 pdgfaa platelet-der--- multicellular organismal development /// cell proliferation growth factor activity membrane Dr.10095.1.A1 at -1.73408 -2.11615 -1.47234 -2.19919 1 0.997562 1 0.978177 0.9782 wu:fk95g04 wu:fk95g04--- --- --- --- Dr.10110.1.S1 a at 3.929761 5.798708 -

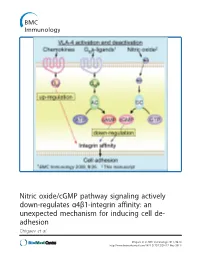

Nitric Oxide/Cgmp Pathway Signaling Actively Down-Regulates Α4β1-Integrin Affinity: an Unexpected Mechanism for Inducing Cell De- Adhesion Chigaev Et Al

Nitric oxide/cGMP pathway signaling actively down-regulates α4β1-integrin affinity: an unexpected mechanism for inducing cell de- adhesion Chigaev et al. Chigaev et al. BMC Immunology 2011, 12:28 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2172/12/28 (17 May 2011) Chigaev et al. BMC Immunology 2011, 12:28 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2172/12/28 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Nitric oxide/cGMP pathway signaling actively down-regulates a4b1-integrin affinity: an unexpected mechanism for inducing cell de-adhesion Alexandre Chigaev*, Yelena Smagley and Larry A Sklar Abstract Background: Integrin activation in response to inside-out signaling serves as the basis for rapid leukocyte arrest on endothelium, migration, and mobilization of immune cells. Integrin-dependent adhesion is controlled by the conformational state of the molecule, which is regulated by seven-transmembrane Guanine nucleotide binding Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs). a4b1-integrin (CD49d/CD29, Very Late Antigen-4, VLA-4) is expressed on leukocytes, hematopoietic progenitors, stem cells, hematopoietic cancer cells, and others. VLA-4 conformation is rapidly up-regulated by inside-out signaling through Gai-coupled GPCRs and down-regulated by Gas-coupled GPCRs. However, other signaling pathways, which include nitric oxide-dependent signaling, have been implicated in the regulation of cell adhesion. The goal of the current report was to study the effect of nitric oxide/cGMP signaling pathway on VLA-4 conformational regulation. Results: Using fluorescent ligand binding to evaluate the integrin activation state on live cells in real-time, we show that several small molecules, which specifically modulate nitric oxide/cGMP signaling pathway, as well as a cell permeable cGMP analog, can rapidly down-modulate binding of a VLA-4 specific ligand on cells pre-activated through three Gai-coupled receptors: wild type CXCR4, CXCR2 (IL-8RB), and a non-desensitizing mutant of formyl peptide receptor (FPR ΔST). -

12) United States Patent (10

US007635572B2 (12) UnitedO States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,635,572 B2 Zhou et al. (45) Date of Patent: Dec. 22, 2009 (54) METHODS FOR CONDUCTING ASSAYS FOR 5,506,121 A 4/1996 Skerra et al. ENZYME ACTIVITY ON PROTEIN 5,510,270 A 4/1996 Fodor et al. MICROARRAYS 5,512,492 A 4/1996 Herron et al. 5,516,635 A 5/1996 Ekins et al. (75) Inventors: Fang X. Zhou, New Haven, CT (US); 5,532,128 A 7/1996 Eggers Barry Schweitzer, Cheshire, CT (US) 5,538,897 A 7/1996 Yates, III et al. s s 5,541,070 A 7/1996 Kauvar (73) Assignee: Life Technologies Corporation, .. S.E. al Carlsbad, CA (US) 5,585,069 A 12/1996 Zanzucchi et al. 5,585,639 A 12/1996 Dorsel et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,593,838 A 1/1997 Zanzucchi et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,605,662 A 2f1997 Heller et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 5,620,850 A 4/1997 Bamdad et al. 5,624,711 A 4/1997 Sundberg et al. (21) Appl. No.: 10/865,431 5,627,369 A 5/1997 Vestal et al. 5,629,213 A 5/1997 Kornguth et al. (22) Filed: Jun. 9, 2004 (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS US 2005/O118665 A1 Jun. 2, 2005 EP 596421 10, 1993 EP 0619321 12/1994 (51) Int. Cl. EP O664452 7, 1995 CI2O 1/50 (2006.01) EP O818467 1, 1998 (52) U.S. -

Adenylyl Cyclase” Exotoxins from Bacillus Anthracis And

Molecular and Cellular Analysis of the “Adenylyl Cyclase” Exotoxins from Bacillus anthracis and Bordetella pertussis Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) der Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät IV – Chemie und Pharmazie – der Universität Regensburg vorgelegt von Corinna Spangler aus Osterhofen/Deggendorf 2010 Die vorliegende Arbeit entstand unter der Leitung von Herrn Prof. Dr. R. Seifert und Herrn Prof. Dr. O. Wolfbeis im Zeitraum von November 2006 bis Januar 2009 am Institut für Analytische Chemie, Chemo‐ und Biosensorik und am Institut für Pharmakologie und Toxikologie der Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät IV – Chemie und Pharmazie – der Universität Regensburg und zwischen Februar 2009 und März 2010 am Institut für Pharmakologie der Medizinischen Hochschule Hannover. Das Promotionsgesuch wurde eingereicht am 07. April 2010. Das Kolloquium findet am 11. Juni 2010 statt. Prüfungsausschuss: Prof. Dr. Armin Buschauer (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Roland Seifert (Erstgutachter) Prof. Dr. Otto Wolfbeis (Zweitgutachter) Prof. Dr. Jens Schlossmann (Drittprüfer) Krise ist ein produktiver Zustand. Man muss ihr nur den Beigeschmack der Katastrophe nehmen. Max Frisch Danksagung Zum Gelingen dieser Arbeit haben viele Menschen beigetragen durch wertvolle Ratschläge, wissenschaftliche Diskussionen, tatkräftige Unterstützung und einer gehörigen Portion Geduld. Ein besonderer Dank gilt Herrn Prof. Roland Seifert für seinen unerschütterlichen Optimismus, die wissenschaftlichen Diskussionen und Anregungen und das Vertrauen, das er in mich gesetzt hat. Herr Seifert, Sie waren immer in der Lage, mich zu motivieren, und haben mir zahlreiche Möglichkeiten eröffnet. Außerdem gilt mein Dank Herrn Prof. Otto Wolfbeis und Herrn Dr. Michael Schäferling für die wissenschaftlichen Diskussionen und die tatkräftige Unterstützung in Sachen Fluoreszenzanalytik. Ich habe an Ihrem Lehrstuhl viel lernen dürfen! Edeltraud Schmid und Annette Stanke danke ich für die Unterstützung in allen Lebenslagen, v.a. -

All Enzymes in BRENDA™ the Comprehensive Enzyme Information System

All enzymes in BRENDA™ The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System http://www.brenda-enzymes.org/index.php4?page=information/all_enzymes.php4 1.1.1.1 alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B1 D-arabitol-phosphate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.2 alcohol dehydrogenase (NADP+) 1.1.1.B3 (S)-specific secondary alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.3 homoserine dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B4 (R)-specific secondary alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.4 (R,R)-butanediol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.5 acetoin dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B5 NADP-retinol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.6 glycerol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.7 propanediol-phosphate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.8 glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NAD+) 1.1.1.9 D-xylulose reductase 1.1.1.10 L-xylulose reductase 1.1.1.11 D-arabinitol 4-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.12 L-arabinitol 4-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.13 L-arabinitol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.14 L-iditol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.15 D-iditol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.16 galactitol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.17 mannitol-1-phosphate 5-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.18 inositol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.19 glucuronate reductase 1.1.1.20 glucuronolactone reductase 1.1.1.21 aldehyde reductase 1.1.1.22 UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.23 histidinol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.24 quinate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.25 shikimate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.26 glyoxylate reductase 1.1.1.27 L-lactate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.28 D-lactate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.29 glycerate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.30 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.31 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.32 mevaldate reductase 1.1.1.33 mevaldate reductase (NADPH) 1.1.1.34 hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase (NADPH) 1.1.1.35 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0240226A1 Mathur Et Al

US 20150240226A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0240226A1 Mathur et al. (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 27, 2015 (54) NUCLEICACIDS AND PROTEINS AND CI2N 9/16 (2006.01) METHODS FOR MAKING AND USING THEMI CI2N 9/02 (2006.01) CI2N 9/78 (2006.01) (71) Applicant: BP Corporation North America Inc., CI2N 9/12 (2006.01) Naperville, IL (US) CI2N 9/24 (2006.01) CI2O 1/02 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Eric J. Mathur, San Diego, CA (US); CI2N 9/42 (2006.01) Cathy Chang, San Marcos, CA (US) (52) U.S. Cl. CPC. CI2N 9/88 (2013.01); C12O 1/02 (2013.01); (21) Appl. No.: 14/630,006 CI2O I/04 (2013.01): CI2N 9/80 (2013.01); CI2N 9/241.1 (2013.01); C12N 9/0065 (22) Filed: Feb. 24, 2015 (2013.01); C12N 9/2437 (2013.01); C12N 9/14 Related U.S. Application Data (2013.01); C12N 9/16 (2013.01); C12N 9/0061 (2013.01); C12N 9/78 (2013.01); C12N 9/0071 (62) Division of application No. 13/400,365, filed on Feb. (2013.01); C12N 9/1241 (2013.01): CI2N 20, 2012, now Pat. No. 8,962,800, which is a division 9/2482 (2013.01); C07K 2/00 (2013.01); C12Y of application No. 1 1/817,403, filed on May 7, 2008, 305/01004 (2013.01); C12Y 1 1 1/01016 now Pat. No. 8,119,385, filed as application No. PCT/ (2013.01); C12Y302/01004 (2013.01); C12Y US2006/007642 on Mar. 3, 2006. -

Springer Handbook of Enzymes

Dietmar Schomburg Ida Schomburg (Eds.) Springer Handbook of Enzymes Alphabetical Name Index 1 23 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York 2010 This work is subject to copyright. All rights reserved, whether in whole or part of the material con- cerned, specifically the right of translation, printing and reprinting, reproduction and storage in data- bases. The publisher cannot assume any legal responsibility for given data. Commercial distribution is only permitted with the publishers written consent. Springer Handbook of Enzymes, Vols. 1–39 + Supplements 1–7, Name Index 2.4.1.60 abequosyltransferase, Vol. 31, p. 468 2.7.1.157 N-acetylgalactosamine kinase, Vol. S2, p. 268 4.2.3.18 abietadiene synthase, Vol. S7,p.276 3.1.6.12 N-acetylgalactosamine-4-sulfatase, Vol. 11, p. 300 1.14.13.93 (+)-abscisic acid 8’-hydroxylase, Vol. S1, p. 602 3.1.6.4 N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase, Vol. 11, p. 267 1.2.3.14 abscisic-aldehyde oxidase, Vol. S1, p. 176 3.2.1.49 a-N-acetylgalactosaminidase, Vol. 13,p.10 1.2.1.10 acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (acetylating), Vol. 20, 3.2.1.53 b-N-acetylgalactosaminidase, Vol. 13,p.91 p. 115 2.4.99.3 a-N-acetylgalactosaminide a-2,6-sialyltransferase, 3.5.1.63 4-acetamidobutyrate deacetylase, Vol. 14,p.528 Vol. 33,p.335 3.5.1.51 4-acetamidobutyryl-CoA deacetylase, Vol. 14, 2.4.1.147 acetylgalactosaminyl-O-glycosyl-glycoprotein b- p. 482 1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, Vol. 32, 3.5.1.29 2-(acetamidomethylene)succinate hydrolase, p. 287 Vol. -

1 Imipramine Treatment and Resiliency Exhibit Similar

Imipramine Treatment and Resiliency Exhibit Similar Chromatin Regulation in the Mouse Nucleus Accumbens in Depression Models Wilkinson et al. Supplemental Material 1. Supplemental Methods 2. Supplemental References for Tables 3. Supplemental Tables S1 – S24 SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S1: Genes Demonstrating Increased Repressive DimethylK9/K27-H3 Methylation in the Social Defeat Model (p<0.001) SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S2: Genes Demonstrating Decreased Repressive DimethylK9/K27-H3 Methylation in the Social Defeat Model (p<0.001) SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S3: Genes Demonstrating Increased Repressive DimethylK9/K27-H3 Methylation in the Social Isolation Model (p<0.001) SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S4: Genes Demonstrating Decreased Repressive DimethylK9/K27-H3 Methylation in the Social Isolation Model (p<0.001) SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S5: Genes Demonstrating Common Altered Repressive DimethylK9/K27-H3 Methylation in the Social Defeat and Social Isolation Models (p<0.001) SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S6: Genes Demonstrating Increased Repressive DimethylK9/K27-H3 Methylation in the Social Defeat and Social Isolation Models (p<0.001) SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S7: Genes Demonstrating Decreased Repressive DimethylK9/K27-H3 Methylation in the Social Defeat and Social Isolation Models (p<0.001) SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S8: Genes Demonstrating Increased Phospho-CREB Binding in the Social Defeat Model (p<0.001) SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S9: Genes Demonstrating Decreased Phospho-CREB Binding in the Social Defeat Model (p<0.001) SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE S10: Genes Demonstrating Increased Phospho-CREB Binding in the Social -

Analysis of Substrate Specificity and Kinetics Of

Analysis of Substrate Specificity and Kinetics of Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases with N’-Methylanthraniloyl-Substituted Purine and Pyrimidine 39,59-Cyclic Nucleotides by Fluorescence Spectrometry Daniel Reinecke1, Frank Schwede2, Hans-Gottfried Genieser2, Roland Seifert1* 1 Institute of Pharmacology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany, 2 Biolog Life Science Institute, Bremen, Germany Abstract As second messengers, the cyclic purine nucleotides adenosine 39,59-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) and guanosine 39,59- cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) play an essential role in intracellular signaling. Recent data suggest that the cyclic pyrimidine nucleotides cytidine 39,59-cyclic monophosphate (cCMP) and uridine 39,59-cyclic monophosphate (cUMP) also act as second messengers. Hydrolysis by phosphodiesterases (PDEs) is the most important degradation mechanism for cAMP and cGMP. Elimination of cUMP and cCMP is not completely understood, though. We have shown that human PDEs hydrolyze not only cAMP and cGMP but also cyclic pyrimidine nucleotides, indicating that these enzymes may be important for termination of cCMP- and cUMP effects as well. However, these findings were acquired using a rather expensive HPLC/mass spectrometry assay, the technical requirements of which are available only to few laboratories. N’-Methylanthraniloyl-(MANT-)labeled nucleotides are endogenously fluorescent and suitable tools to study diverse protein/nucleotide interactions. In the present study, we report the synthesis of new MANT-substituted cyclic purine- and pyrimidine nucleotides that are appropriate to analyze substrate specificity and kinetics of PDEs with more moderate technical requirements. MANT-labeled nucleoside 39,59-cyclic monophosphates (MANT-cNMPs) are shown to be substrates of various human PDEs and to undergo a significant change in fluorescence upon cleavage, thus allowing direct, quantitative and continuous determination of hydrolysis via fluorescence detection.