A Prehistory of the Exclusive Right of Public Performance for Musical Compositions * Zvi S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

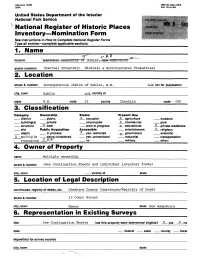

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ' National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name H historic DUBLIN r-Offl and/or common (Partial Inventory; Historic & Architectural Properties) street & number Incorporation limits of Dublin, N.H. n/W not for publication city, town Dublin n/a vicinity of state N.H. code 33 county Cheshire code 005 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public , X occupied X agriculture museum building(s) private -_ unoccupied x commercial park structure x both work in progress X educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object in process x yes: restricted X government scientific X multiple being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation resources X N/A" no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple ownership street & number (-See Continuation Sheets and individual inventory forms) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Cheshire County Courthouse/Registry of Deeds street & number 12 Court Street city, town Keene state New Hampshire 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheets has this property been determined eligible? _X_ yes _JL no date state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description N/A: See Accompanying Documentation. Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered __ original site _ggj|ood £ __ ruins __ altered __ moved date _1_ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance jf Introductory Note The ensuing descriptive statement includes a full exposition of the information requested in the Interim Guidelines, though not in the precise order in which. -

Dorchester Pope Family

A HISTORY OF THE Dorchester Pope Family. 1634-1888. WITH SKETCHES OF OTHER POPES IN ENGLAND AND AMERICA, AND NOTES UPON SEVERAL INTERMARRYING FAMILIES, 0 CHARLES HENRY POPE, MllMBIUl N. E. HISTOalC GENIIALOGlCAl. SOCIETY. BOSTON~ MASS.: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR, AT 79 FRANKLIN ST. 1888 PRESS OF L. BARTA & Co., BOSTON. BOSTON, MA88,,.... (~£P."/.,.. .w.;,.!' .. 190 L.. - f!cynduLdc ;-~,,__ a.ut ,,,,-Mrs. 0 ~. I - j)tt'"rrz-J (i'VU ;-k.Lf!· le a, ~ u1--(_,fl.,C./ cU!.,t,, u,_a,1,,~{a"-~ t L, Lt j-/ (y ~'--? L--y- a~ c/4-.t 7l~ ~~ -zup /r,//~//TJJUJ4y. a.&~ ,,l E kr1J-&1 1}U, ~L-U~ l 6-vl- ~-u _ r <,~ ?:~~L ~ I ~-{lu-,1 7~ _..l~ i allll :i1tft r~,~UL,vtA-, %tt. cz· -t~I;"'~::- /, ~ • I / CJf:z,-61 M, ~u_, PREFACE. IT was predicted of the Great Philanthropist, "He shall tum the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the hearts of children to their fathers." The writer seeks to contribute something toward the development of such mutual afiection between the members of the Pope Family. He has found his own heart tenderly drawn toward all whose names he has registered and whose biographies he has at tempted to write. The dead are his own, whose graves he has sought to strew with the tributes of love ; the living are his own, every one of whose careers he now watches with strong interest. He has given a large part of bis recreation hours and vacation time for eight years to the gathering of materials for the work ; written hundreds of letters ; examined a great many deeds and wills, town journals, church registers, and family records ; visited numerous persons and places, and pored over a large number of histories of towns and families ; and has gathered here the items and entries thus discovered. -

The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act

Volume 104 Issue 2 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 104, 1999-2000 1-1-2000 The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act Mark R. Shulman Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Mark R. Shulman, The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act, 104 DICK. L. REV. 289 (2000). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol104/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act Mark R. Shulman* Perhaps it is a universal truth that the loss of liberty at home is to be charged to provisions against danger; real or pretended, from abroad. -James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, May 1798' I. Introduction to "National Security" The National Security Act of 19472 and its successors drew the blueprint of the Cold War domestic political order. This regime centralized control of the military services-the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and a newly separate Air Force-in a single executive branch department. It created a new professional organization to collect and analyze foreign intelligence, the Central Intelligence Agency. And at the center of this new national security apparatus, a National Security Council would eventually establish foreign policy by coordinating intelligence and directing military and para-military forces, as well as supervising a National Security Resources Board. -

"1683-1920"; the Fourteen Points and What Became of Them--Foreign

^^0^ ^oV^ '•^0^ 4^°^ '/ COPYRIGHT BY 1920 g)CU566029 ^ PUBLISHED BY CONCORD PUBLISHING COMPANY INCORPORATED NEW YORK, U. S. A. ^^^^^eM/uj^ v//^j^#<>tdio ^t^^u^^ " 1 683- 1 920 The Fourteen Points and What Became of Them— Foreign Propaganda in the Public Schools — Rewriting the History of the United States—The Espionage Act and How it Worked— "Illegal and Indefensible Blockade" of the Central Powers— 1.000.000 Victims of Starvation—Our Debt to France and to Germany—The War Uote in Congress — Truth About the Belgian Atrocities— Our Treaty with Germany and How Observed— The Alien Property Custodianship- Secret Will of Cecil Rhodes— Racial Strains in American Life — Germantown Settle- ment of 1683 And a Thousand Other Topics by Frederick Frankun Schrader Former Secretary Republican Congressional Committee and Author "Republican Campaign Text Book. 1898.** (i PREFACE WITH the ending of the war many books will be released dealing with various questions and phases of the great struggle, some of them perhaps impartial, but the majority written to make propaganda for foreign nations with a view to rendering us dissatisfied with our country and imposing still "•- -v,^^ ,it^^,n fiiA iVnorance. indifference and credulity of the Amer- NOTE The short quotations from Mere Literature, by President raised Wi -fvr'i oodrow Wilson, printed on pages II, 95, 166, 224, and 226 of ,, this volume are used by special arrangement with Messrs. Houghton g and Mifflin Company, A blanket indictment has been found against a whole race. That race comprises upward of 26 per cent, of the American people and has been a stalwart factor in American life since the middle of the seventeenth century. -

Catalog # 215 (2 Nd Edition, Enlarged)

WOMEN On-Line Only: Catalog # 215 (2 nd edition, enlarged) Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] women On-Line Only Catalog # 215 nd (2 edition, enlarged ) Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 5% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com or www.ABAA.org . MULIERES HOMINES NON ESSE - ARE WOMEN HUMAN? 1. [ACIDALIYS, Valens,?] GEDDICCVS, (Gedik) Simon . DEFENSIO SEXUS MULIEBRIS, Opposita futilissimae disputationi recenss editae, qua suppresso authoris & authoris & typographi nomine blaspheme contenditur, Mulieres homines non esse. Leipzig: Michael Lantzenberger (for Henning Grosse), 1595. First Edition. 4to, (31) leaves (lacks last blank), title-page neatly mounted on a stub, with printer's mark on the title-page. BOUND WITH/ [ACIDALIYS, Valens,?] DISPUTATIO NOVA CONTRA MULIERES qua probatur eas Homines non esse. [ np, np, 1195 (but ca 1660). 4to, (12) leaves. The two works bound together in quarter blue morocco (a bit faded and rubbed, upper part of spine gone), marble boards, red morocco label with gilt lettering on the spine, some light browning, but a fine copy (the second tract is a little smaller than the first). -

GP Putnam's Sons

• •-••. -•,V'r..j*.i..4-v..'- ...• i'-' •-.' --, TP" •• .;;•••••'••.-•'''•.'•:*•;.••*•, :'.• ..,",•••.•(; • Coincidental Commentaries SIR:—To the roll-call of prophets of the present war can be added the ncimes of two Americans, Woodrow Wilson and Brooks Adams. In 1920 Wilson must be thought to have foreseen the recent conquest of Europe when he warned us: "If we keep out of this agreement, if we re fuse to join in underwriting the peace of civilization, then a fresh attempt will be made to crush the small new nations of Europe." As he must also be thought to have foreseen our cur rent colossal armament outlay in the same year when he declared: "Iso lated we may some day be indeed; and not because we wish to be. When that day comes we shall have to arm to the teeth to preserve our existence." Adams' prophecies occur in his "America's Economic Supremacy" which was published in 1900. Applic able almost equally to the first World War and to its renewal, they predict an assault upon Britain by a Conti nental Coalition formed for that pur pose, and show the inevitability of our becoming involved as an ally of Britain. Many of Adams' images fit "He edits the Gory Gazette." the current pattern closely enough to have been written only yesterday, not forty years ago. It should be added knows as many words as the author you noticed it made a dent on the that at the close of the last War he of "The Tempest," himself—even if he memory of Miss Foyle? predicted its renewal "within at fur has to fabricate them out of his own CHRISTOPHER MORLEY. -

Barnarb College BARNARD COLLEGE ARCHIVES 0?

1902 /Ifcortarboarb Barnarb College BARNARD COLLEGE ARCHIVES 0? H. C. KOCH 6 CO. 125th Street, West ; bet. Lenox and Seventh Avenues EVERYTHING FOR EVERYBODY in this, the most accessible and comfortable department store in Manhattan. Advance styles, dependable grades and lowest prices, the rule without exception here. SUITS. : JACKETS. : FURS. : MILLINERY. : UNDERWEAR, : SHOES, : GLOVES, RIBBONS, : NECKWEAR, : HANDKERCHIEFS, : UMBRELLAS, : ETC.. ETC. THREE ITEMS OF SPECIAL INTEREST NOT OBTAINABLE ELSEWHERE: Sole Agents for New York of the " Z. Z. ELAINE" CORSETS. THE -CECIL" GLOVE. Famous Shoe for Women . Sole importers of this celebrated make A reliable, stylish Glove imported by " QUEEN QUALITY." — a large assortment of shapes show- us from France and high-grade in every ing many decided improvements, thus particular. A host of regular patrons Beauty, ease and service are the dis- covering every demand of varying appreciate this value—and each new tinguishing features of these famous figures, perfect comfort arid absolute customer means a new endorser. An Shoes. Many styles to choose from symmetry in every pair. enormous variety of the best colors, in for street, dress, home, or outing, A great variety of colors—complete both suede and kid, always to be Boots, $3.00 . Oxfords, $2.50 range of prices, every one moderate. found here . $1.00 *sgT Broadway Cars with Free Transfer to 125th Street line bring you right to our door.^^i Piatt's Persons of taste carry FIN DESIECLT UMBRELLAS Smallest- Rolling Lightest, Strongest hlorides , f 1 BARCLAY ST., near Broadway The Household Disinfectant. B. Ladies' Umbrellas, for Birthday and Instantly N. — An odorless, colorless liquid ; powerful, safe and cheap. -

For Social Research, New· York City

.·.-,. / THE NEW SCHOOL 66 W 12th ST NEW YORK 11 ALGONQUIN 4-2567 April 19, 1944 Dear Mr.,)feinsteini ,/ I am_,..--glad to enclose the list of our refugee sclrolars who were, or ·atill--- are, con nected with the New School. Those on the list for whom I have additional bio~aphical ma terial in my files bear a mark('.'1) before their names. However, it would take quite some time to go over the entire material in order to forward you the essential data. May I therefore suggest that you first look through the whole list, and tell me exactly which specific questions, in ad dition to those answered on the list, you would like to have answered. This would make our work here more efficient. Sincerely yours, ~ Mr. I. M. Weinstein Special Assistant to the Executive Director J Executive Office of the ~resident War Refugee Board Washington 25 1 D.O. _Enclosure. ___ ._ .... LIST OF l,,6'7'REFUGEE SCHOLARS .AND ARTISTS WHO C.AAIB TO THE NE\'! SCHOOL FOR SOCIAL RZ§EARCH. NEW YORK CITY CoUn.try Present .l!'oreign University Now working or .of Origin Nntj onelity l1ald or Otlier -Oounectiqn teaching at . J<.l t, Franz L. .!lustria Stateless Economics, Ph.D., Vienna Lecturer,. Graduate Faculty~ Statistics, New i:ichool fOJ.". Social li~ · A:a.thematics. searc})., New York City; Chie:t' Jmalyst, ....conomic in"." · stitute, Ne1v Yor]t City . ' .. 1'.rnheim, .Rudolf Gernn:ny i:itateless Psychology, ;,.ssi s tant editor, Int or• Lecturer,. Graduate ia~lty, Theory of .ti.rt national Institute of Narr Ochool for Social:~;.;. -

DUBLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE: HISTORIC RESOURCES INVENTORY Cheshire County

DUBLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE: HISTORIC RESOURCES INVENTORY Cheshire County 1. DUBLIN LAKE HISTORIC DISTRICT i 2. Dublin, N.H. 03444. jCheshire County. 3. Historic district of occupied properties, both privately and publicly owned, - . comprised entirely o£ residences, seasonal cottages and two clubhouses. j 4. Multiple Ownership, j (See continuation sheets.) 5. Location of Legal Description. Same as overall nomination. Town of Dublin Assessors Property Map and Lot numbers appear in upper right hand corner (Item #22) of:all Individual Inventory forms. 6. Prior Surveys. Same!as overall nomination. 7. Description. (See continuation sheets.) 8. Significance. (See Continuation sheets.) 9. Bibliographical References. Same as overall nomination. 10. Geographical Data: ; A. Acreage: 660 plus 239 water: 899 B. UTM References: j F Z18 E738-J050 N4756-495 G Z18 E736^400 N4753-695 H Z18 E738- 795 N4753-145 J Z18 E739- 600 N4754-725 C. Verbal Boundary Description. i The Dublin Lake District boundary generally follows a line uniformly setback 1000 feet from the shore of Dublin Lake (corresponding to the line extablished in the 1926 Conservation easement) with one indentation to accommodate the Dublin Village District boundary, and four additions to include architec turally and historically significant properties that were integral parts of the late 19th - 0arly 20th century summer colony centered on Dublin Lake. | The boundary is as follows: Commencing at Route 101 at a point 1000 feet east of Dublin Lake, thence south and west on the 1000-foot setback line to the 390,000 East coordinate (N.H. Grid system), thence west along the 1520 foot elevation on the! south side of Lone Tree Hill to the 387,800 East coordinate (N.H. -

Anna L. Snelling's Kabaosa (1842)

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Articles University Libraries 2015 “With Extreme Diffidence”: Anna L. Snelling’s Kabaosa (1842) A Provisional Publishing History and Census Robert Beasecker Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/library_sp Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Beasecker, Robert, "“With Extreme Diffidence”: Anna L. Snelling’s Kabaosa (1842) A Provisional Publishing History and Census" (2015). Articles. Paper 52. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/library_sp/52 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “With Extreme Diffidence”: Anna L. Snelling’s Kabaosa (1842) 1 A Provisional Publishing History and Census Robert Beasecker Director of Special Collections & University Archives Grand Valley State University Libraries A little-known American novel set in the Great Lakes region during the War of 1812, Kabaosa has left a negligible amount of evidence concerning its conception, writing, printing, and ultimate publication. However, in spite of the absence of the author’s manuscript and the printer’s records, a plausible reconstruction of its publication history can be made using the extant documentary evidence as well as an examination of surviving copies of the book itself. What at first glance appeared to be a self-published run-of-the-mill historical romance of marginal literary merit was discovered to have a much more complex and interesting life story. There is scant—and often incorrect—biographical information about the author of Kabaosa , Anna Lowell Putnam Snelling (1812-1865).2 She was born in Brunswick, Maine to a venerable Massachusetts family: her parents were Henry Putnam, a lawyer, and Catherine Palmer, a schoolteacher; her great uncle was the Revolutionary War hero Israel Putnam of Bunker Hill fame. -

The Roman Index Its Latest Historian

The Roman Index and Its Latest Historian A Critical Review of "The Censorship of the Church of Rome" by George Haven Putnam By JOSEPH HILGERS, S. J. Reprinted from the CATHOLIC FORTNIGHTLY REVIEW, with an Introductory Note by ARTHUR PREUSS 1908 PRINTED BY THE SOCIETY OF THE DIVINE WORD, TECHNY, ILLINOIS NIHIL OBSTAT JOANNES PEIL, S. V. D., Cens. dep. Techfiy, ///., Jtily /7, igo8 IMPRIMATUR JACOBUS EDUARDUS, Archiepiscopus Chicagiensis Chicago, III., July ig, igo8 Introductory Note The following paper appeared originally in the CATHOUC FORT- 1 NIGHTI^Y R^viDw. It was written at my request by the learned atithor, whose large work, Der Index der verbotenen Biicher2 in sei- ner neuen Fassung dargelegt und rechtlich-historisch gewilrdigt, recently supplemented by a smaller but no less important volume, Die Bucher- verbote in Papstbriefen—Kanonistisch-bibliographische Studie,3 have deservedly obtained for him an international reputation as one of the "foremost specialists in the matt'er of forbidden books." Mr. Put- nam himself calls the first-mentioned work a "scholarly and author- itative treatise" and "by far the most important statement that had come into print presenting the Church side of the questions at issue."4 For the English translation I am responsible, though Father Hilgers has had-the kindness to revise it after it had appeared in the R^viEw. Mr. Putnam provoked this criticism himself. He pounced upon an obiter dictum that appeared in this R^viEw last year, with reference to his work, and gave me an epistolary scolding for pro- nouncing judgment upon The Censorship of the Church of Rome with- out having read it, at the same time offering me a copy for review. -

![Low-Mills Family Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Sun Jan 28 15:33:31 EST 2018] [XSLT Processor: SAXON 9](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3844/low-mills-family-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-sun-jan-28-15-33-31-est-2018-xslt-processor-saxon-9-6973844.webp)

Low-Mills Family Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Sun Jan 28 15:33:31 EST 2018] [XSLT Processor: SAXON 9

Low-Mills Family Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2017 Revised 2017 July Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms005016 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm81030619 Prepared by Raymond Eichman, George F. Williss, David Mathisen, and Karen Linn Femia with the assistance of Marjorie Torney Revised and expanded by Nate Scheible Collection Summary Title: Low-Mills family papers Span Dates: 1767-1971 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1806-1940) ID No.: MSS30619 Creator: Low family Creator: Mills family Extent: 9,000 items ; 39 containers plus 1 oversize ; 14.6 linear feet ; 2 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Prominent family engaged in China trade. Correspondence, diaries, journals, writings and genealogical material documenting the Low, Mills, Hillard, and Loines families from the early years of the nineteenth century until the middle of the twentieth. Of special interest are papers concerning the family's activities in the China trade and the journal of Harriet Low Hillard documenting her stay in Macau, 1829-1834. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Hellard family. Hillard family. Hillard, Harriet Low, 1809-1877. Harriet Low Hillard papers. Hummel, Arthur W.