The Twilight of the Opera Pirates: a Prehistory of the Exclusive Right of Public Performance for Musical Compositions Zvi S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113

The Inventory of the Ralph Ingersoll Collection #113 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center John Ingersoll 1625-1684 Bedfordshire, England Jonathan Ingersoll 1681-1760 Connecticut __________________________________________ Rev. Jonathan Ingersoll Jared Ingersoll 1713-1788 1722-1781 Ridgefield, Connecticut Stampmaster General for N.E Chaplain Colonial Troops Colonies under King George III French and Indian Wars, Champlain Admiralty Judge Grace Isaacs m. Jonathan Ingersoll Baron J.C. Van den Heuvel Jared Ingersoll, Jr. 1770-1823 1747-1823 1749-1822 Lt. Governor of Conn. Member Const. Convention, 1787 Judge Superior and Supreme Federalist nominee for V.P., 1812 Courts of Conn. Attorney General Presiding Judge, District Court, PA ___ _____________ Grace Ingersoll Charles Anthony Ingersoll Ralph Isaacs Ingersoll m. Margaret Jacob A. Charles Jared Ingersoll Joseph Reed Ingersoll Zadock Pratt 1806- 1796-1860 1789-1872 1790-1878 1782-1862 1786-1868 Married General Grellet State=s Attorney, Conn. State=s Attorney, Conn. Dist. Attorney, PA U.S. Minister to England, Court of Napoleon I, Judge, U.S. District Court U.S. Congress U.S. Congress 1850-1853 Dept. of Dedogne U.S. Minister to Russia nom. U.S. Minister to under Pres. Polk France Charles D. Ingersoll Charles Robert Ingersoll Colin Macrae Ingersoll m. Julia Helen Pratt George W. Pratt Judge Dist. Court 1821-1903 1819-1903 New York City Governor of Conn., Adjutant General, Conn., 1873-77 Charge d=Affaires, U.S. Legation, Russia, 1840-49 Theresa McAllister m. Colin Macrae Ingersoll, Jr. Mary E. Ingersoll George Pratt Ingersoll m. Alice Witherspoon (RI=s father) 1861-1933 1858-1948 U.S. Minister to Siam under Pres. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

Charles Ingersoll: the ^Aristocrat As Copperhead

Charles Ingersoll: The ^Aristocrat as Copperhead HE INGERSOLL FAMILY is one of America's oldest. The first Ingersoll came to America in 1629, just nine years after the T^Mayflower. The first Philadelphia Ingersoll was Jared Inger- soll, who came to the city in 1771 as presiding judge of the King's vice-admiralty court. Previously, he had been the King's colonial agent and stamp master in Connecticut. During the Revolution, Jared remained loyal to the Crown. He stayed in Philadelphia for the first two years of the war, but in 1777, when he and other Tories were forced to leave, he returned to Connecticut, where he lived quietly until his death in 1781.1 Jared's son, Jared, Jr., was the first prominent Philadelphia Inger- soll. He came to Philadelphia with his father in 1771, studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1778. Unlike his father, Jared, Jr., wholeheartedly supported the Revolution. Subsequently, he was a member of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, a member of the city council, city solicitor, attorney general of Pennsylvania, and United States District Attorney. Politically, he was an ardent Fed- eralist, but politics and affairs of state were never his prime interest; his real interest was the law, and most of his time and energy was devoted to his legal practice.2 Jared, Jr.'s, son, Charles Jared Ingersoll, was probably the most interesting of the Philadelphia Ingersolls. Like his father, grand- father, and most of the succeeding generations of Ingersolls, Charles Jared was a lawyer. He began a practice in Philadelphia in 1802, but devoted much of his time to politics. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

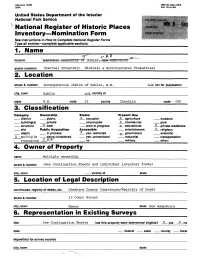

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ' National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name H historic DUBLIN r-Offl and/or common (Partial Inventory; Historic & Architectural Properties) street & number Incorporation limits of Dublin, N.H. n/W not for publication city, town Dublin n/a vicinity of state N.H. code 33 county Cheshire code 005 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public , X occupied X agriculture museum building(s) private -_ unoccupied x commercial park structure x both work in progress X educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object in process x yes: restricted X government scientific X multiple being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation resources X N/A" no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple ownership street & number (-See Continuation Sheets and individual inventory forms) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Cheshire County Courthouse/Registry of Deeds street & number 12 Court Street city, town Keene state New Hampshire 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheets has this property been determined eligible? _X_ yes _JL no date state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description N/A: See Accompanying Documentation. Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered __ original site _ggj|ood £ __ ruins __ altered __ moved date _1_ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance jf Introductory Note The ensuing descriptive statement includes a full exposition of the information requested in the Interim Guidelines, though not in the precise order in which. -

Dorchester Pope Family

A HISTORY OF THE Dorchester Pope Family. 1634-1888. WITH SKETCHES OF OTHER POPES IN ENGLAND AND AMERICA, AND NOTES UPON SEVERAL INTERMARRYING FAMILIES, 0 CHARLES HENRY POPE, MllMBIUl N. E. HISTOalC GENIIALOGlCAl. SOCIETY. BOSTON~ MASS.: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR, AT 79 FRANKLIN ST. 1888 PRESS OF L. BARTA & Co., BOSTON. BOSTON, MA88,,.... (~£P."/.,.. .w.;,.!' .. 190 L.. - f!cynduLdc ;-~,,__ a.ut ,,,,-Mrs. 0 ~. I - j)tt'"rrz-J (i'VU ;-k.Lf!· le a, ~ u1--(_,fl.,C./ cU!.,t,, u,_a,1,,~{a"-~ t L, Lt j-/ (y ~'--? L--y- a~ c/4-.t 7l~ ~~ -zup /r,//~//TJJUJ4y. a.&~ ,,l E kr1J-&1 1}U, ~L-U~ l 6-vl- ~-u _ r <,~ ?:~~L ~ I ~-{lu-,1 7~ _..l~ i allll :i1tft r~,~UL,vtA-, %tt. cz· -t~I;"'~::- /, ~ • I / CJf:z,-61 M, ~u_, PREFACE. IT was predicted of the Great Philanthropist, "He shall tum the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the hearts of children to their fathers." The writer seeks to contribute something toward the development of such mutual afiection between the members of the Pope Family. He has found his own heart tenderly drawn toward all whose names he has registered and whose biographies he has at tempted to write. The dead are his own, whose graves he has sought to strew with the tributes of love ; the living are his own, every one of whose careers he now watches with strong interest. He has given a large part of bis recreation hours and vacation time for eight years to the gathering of materials for the work ; written hundreds of letters ; examined a great many deeds and wills, town journals, church registers, and family records ; visited numerous persons and places, and pored over a large number of histories of towns and families ; and has gathered here the items and entries thus discovered. -

The Signers of the U.S. Constitution

CONSTITUTIONFACTS.COM The U.S Constitution & Amendments: About the Signers (Continued) The Signers of the U.S. Constitution On September 17, 1787, the Constitutional Convention came to a close in the Assembly Room of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There were seventy individuals chosen to attend the meetings with the initial purpose of amending the Articles of Confederation. Rhode Island opted to not send any delegates. Fifty-five men attended most of the meetings, there were never more than forty-six present at any one time, and ultimately only thirty-nine delegates actually signed the Constitution. (William Jackson, who was the secretary of the convention, but not a delegate, also signed the Constitution. John Delaware was absent but had another delegate sign for him.) While offering incredible contributions, George Mason of Virginia, Edmund Randolph of Virginia, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts refused to sign the final document because of basic philosophical differences. Mainly, they were fearful of an all-powerful government and wanted a bill of rights added to protect the rights of the people. The following is a list of those individuals who signed the Constitution along with a brief bit of information concerning what happened to each person after 1787. Many of those who signed the Constitution went on to serve more years in public service under the new form of government. The states are listed in alphabetical order followed by each state’s signers. Connecticut William S. Johnson (1727-1819)—He became the president of Columbia College (formerly known as King’s College), and was then appointed as a United States Senator in 1789. -

ELECTORAL VOTES for PRESIDENT and VICE PRESIDENT Ø902¿ 69 77 50 69 34 132 132 Total Total 21 10 21 10 21 Va

¿901¿ ELECTORAL VOTES FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT ELECTORAL VOTES FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT 901 ELECTION FOR THE FIRST TERM, 1789±1793 GEORGE WASHINGTON, President; JOHN ADAMS, Vice President Name of candidate Conn. Del. Ga. Md. Mass. N.H. N.J. Pa. S.C. Va. Total George Washington, Esq ................................................................................................... 7 3 5 6 10 5 6 10 7 10 69 John Adams, Esq ............................................................................................................... 5 ............ ............ ............ 10 5 1 8 ............ 5 34 Samuel Huntington, Esq ................................................................................................... 2 ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 2 1027 John Jay, Esq ..................................................................................................................... ............ 3 ............ ............ ............ ............ 5 ............ ............ 1 9 John Hancock, Esq ............................................................................................................ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 2 1 1 4 Robert H. Harrison, Esq ................................................................................................... ............ ............ ............ 6 ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ........... -

Edward Sturgis of Yarmouth, Massachusetts 1613-1695

EDWARD STURGIS OF YARMOUTH, MASSACHUSETTS 1613-1695 AND HIS DESCENDANTS ROGER FAXTON STURGIS, EDITOR PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION AT THE $tanbope preee BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 1914 (PlPase paste in your copy of Book) ADDENDA AND ERRATA. EDWARD STURGIS AND HIS DESCENDANTS. RocrnR FAXTON STURGIS, Editor. p. 22 In thinl line of third paragraph strike out "name m1kn0wn" brackets and substitute "Wendall." p. 22 In reference to Samuel Sturgis (D) strike 011t all after the date 1751 the third paragraph and substitute the following: - ''Fora third wife he marrh•d Abigail Otis a11d had a s011 J (E) born Ot:tuber l':I, 17::i7 aml a daughter l,ncretia CE) l November 11, 1758 (B. '.r. R. 2-275). Administration was grar upon his estate April 25, 1762, he being described as "of llarm:ta gentleman," to .Joseph Otis (his brother-in-law) and to his wi< .Abigail (B. 1'. C. vol. 10, p. 101). His estate was insolve11t am mention is made of children." p. 22 Strike out the reference to Prince Stnrgis (DJ aml sul.JstitutP following paragraph: - " Prince Sturgis (D), the fourth son, married October 12. 1 ElizalJelh Fayerweather and died at Dorchester, Massaeh11se 1779. There was one daughter of this marriage, ElizalJeth lJaptized February 7, 1740 and married December 2fl, liGl, Art Savage. They had five children. The eldest, Faith or Fidt married lkv. Hichard Munkhouse. Tlle others dir,d unmarrirc pp. 22 & 23. Strike out the reference to f-;anrnel (E) beginning at the foo µage 22 and substitute the following: - " Samnel (E), the other so11, married Lydia Crocker, daugl of Cornelius a11d Lydia (.J enkius) Crocker, aml had one child Sn (F) born November 8, 17G0 (4 B. -

History of the U.S. Attorneys

Bicentennial Celebration of the United States Attorneys 1789 - 1989 "The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer. He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor– indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one." QUOTED FROM STATEMENT OF MR. JUSTICE SUTHERLAND, BERGER V. UNITED STATES, 295 U. S. 88 (1935) Note: The information in this document was compiled from historical records maintained by the Offices of the United States Attorneys and by the Department of Justice. Every effort has been made to prepare accurate information. In some instances, this document mentions officials without the “United States Attorney” title, who nevertheless served under federal appointment to enforce the laws of the United States in federal territories prior to statehood and the creation of a federal judicial district. INTRODUCTION In this, the Bicentennial Year of the United States Constitution, the people of America find cause to celebrate the principles formulated at the inception of the nation Alexis de Tocqueville called, “The Great Experiment.” The experiment has worked, and the survival of the Constitution is proof of that. -

The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act

Volume 104 Issue 2 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 104, 1999-2000 1-1-2000 The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act Mark R. Shulman Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Mark R. Shulman, The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act, 104 DICK. L. REV. 289 (2000). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol104/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act Mark R. Shulman* Perhaps it is a universal truth that the loss of liberty at home is to be charged to provisions against danger; real or pretended, from abroad. -James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, May 1798' I. Introduction to "National Security" The National Security Act of 19472 and its successors drew the blueprint of the Cold War domestic political order. This regime centralized control of the military services-the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and a newly separate Air Force-in a single executive branch department. It created a new professional organization to collect and analyze foreign intelligence, the Central Intelligence Agency. And at the center of this new national security apparatus, a National Security Council would eventually establish foreign policy by coordinating intelligence and directing military and para-military forces, as well as supervising a National Security Resources Board. -

Originalism, Nonoriginalist Precedent, and the Common Good

Volume 36 Issue 2 Spring Spring 2006 An Originalist Theory of Precedent: Originalism, Nonoriginalist Precedent, and the Common Good Lee J. Strang Recommended Citation Lee J. Strang, An Originalist Theory of Precedent: Originalism, Nonoriginalist Precedent, and the Common Good, 36 N.M. L. Rev. 419 (2006). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol36/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The University of New Mexico School of Law. For more information, please visit the New Mexico Law Review website: www.lawschool.unm.edu/nmlr AN ORIGINALIST THEORY OF PRECEDENT: ORIGINALISM, NONORIGINALIST PRECEDENT, AND THE COMMON GOOD LEE J. STRANG* I. INTRODUCTION There is substantial scholarly disagreement on whether and in what manner prior decisions of a court-especially the U.S. Supreme Court-interpreting the Constitution bind the same court' later in time.2 This is despite the consensus of American legal practice that prior constitutional decisions do bind later courts.' At the heart of the debate surrounding precedent is the tension between our written Constitution, which is the supreme law of the land,4 and the role of the unelected Supreme Court in exercising constitutional judicial review.' * Assistant Professor of Law, Ave Maria School of Law. I would like to thank my loving wife Elizabeth for her sacrifice to allow me to write this Article. Many thanks to Bryce Poole for his excellent research assistance on this Article. I would also like to thank the participants at the Thomistic Understandingof Natural Law as the Foundation of Positive Law conference at Ptzminy P6ter Catholic University, Faculty of Law and Political Sciences, in Budapest, Hungary (organized by Thomas International), and Howard Bromberg, Bruce Frohnen, Kevin Lee, Ed Lyons, and Steve Safranek.