The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iron & Steel Entrepreneurs on the Delaware GSL22 12.15

Today we get excited about iPhones, iPads, and the like, but 160 years ago, when the key innovations were happening in railroads, iron, and steel, many people actually got excited about . I-beams! And among the centers of such excitement was Trenton, New Jersey. Figure 1: Petty's Run Steel renton became a center of these iron and steel innovations in the 19th Site, Trenton, 2013. In the century for the same reasons that spur innovation today—location, 1990s Hunter Research, Inc. uncovered the foundation of Tinfrastructure, skilled workers, and entrepreneurs. The city’s Benjamin Yard's 1740s steel resources attracted three of the more brilliant and visionary furnace, one of the earliest entrepreneurs of the 1840s—Peter Cooper, Abram S. Hewitt, and John A. steel making sites in the Roebling. They established iron and steel enterprises in Trenton that colonies. The site lies lasted for more than 140 years and helped shape modern life with between the N.J. State innovations in transportation, construction, and communications. Their House and the Old Barracks, legacy in New Jersey continues today with landmark suspension background, and the State and Mercer County have bridges, one of the State’s finest historic parks, repurposed industrial preserved and interpreted it. buildings, one of the best company towns in America, and in a new C.W. Zink museum. Abram Hewitt, Peter Cooper’s partner and future son-in-law, highlighted Trenton’s assets in 1853: “The great advantage of Trenton is that it lies on the great route between New York and Philadelphia” which were the two largest markets in the country. -

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916 Table of Contents OFFICERS AND COMMITTEES .......................................................................................5 PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH TO THIRTY-NINTH MEETINGS .............................................................................................7 PAPERS EXTRACTS FROM LETTERS OF THE REVEREND JOSEPH WILLARD, PRESIDENT OF HARVARD COLLEGE, AND OF SOME OF HIS CHILDREN, 1794-1830 . ..........................................................11 By his Grand-daughter, SUSANNA WILLARD EXCERPTS FROM THE DIARY OF TIMOTHY FULLER, JR., AN UNDERGRADUATE IN HARVARD COLLEGE, 1798- 1801 ..............................................................................................................33 By his Grand-daughter, EDITH DAVENPORT FULLER BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF MRS. RICHARD HENRY DANA ....................................................................................................................53 By MRS. MARY ISABELLA GOZZALDI EARLY CAMBRIDGE DIARIES…....................................................................................57 By MRS. HARRIETTE M. FORBES ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TREASURER ........................................................................84 NECROLOGY ..............................................................................................................86 MEMBERSHIP .............................................................................................................89 OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY -

THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS by Harlan C. Herner a Thesis

The Arizona rough riders Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Herner, Charles Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 02:07:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551769 THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS b y Harlan C. Herner A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1965 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of require ments for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under the rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of this material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: MsA* J'73^, APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: G > Harwood P. -

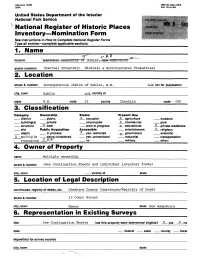

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ' National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name H historic DUBLIN r-Offl and/or common (Partial Inventory; Historic & Architectural Properties) street & number Incorporation limits of Dublin, N.H. n/W not for publication city, town Dublin n/a vicinity of state N.H. code 33 county Cheshire code 005 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public , X occupied X agriculture museum building(s) private -_ unoccupied x commercial park structure x both work in progress X educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object in process x yes: restricted X government scientific X multiple being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation resources X N/A" no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple ownership street & number (-See Continuation Sheets and individual inventory forms) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Cheshire County Courthouse/Registry of Deeds street & number 12 Court Street city, town Keene state New Hampshire 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheets has this property been determined eligible? _X_ yes _JL no date state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description N/A: See Accompanying Documentation. Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered __ original site _ggj|ood £ __ ruins __ altered __ moved date _1_ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance jf Introductory Note The ensuing descriptive statement includes a full exposition of the information requested in the Interim Guidelines, though not in the precise order in which. -

Dorchester Pope Family

A HISTORY OF THE Dorchester Pope Family. 1634-1888. WITH SKETCHES OF OTHER POPES IN ENGLAND AND AMERICA, AND NOTES UPON SEVERAL INTERMARRYING FAMILIES, 0 CHARLES HENRY POPE, MllMBIUl N. E. HISTOalC GENIIALOGlCAl. SOCIETY. BOSTON~ MASS.: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR, AT 79 FRANKLIN ST. 1888 PRESS OF L. BARTA & Co., BOSTON. BOSTON, MA88,,.... (~£P."/.,.. .w.;,.!' .. 190 L.. - f!cynduLdc ;-~,,__ a.ut ,,,,-Mrs. 0 ~. I - j)tt'"rrz-J (i'VU ;-k.Lf!· le a, ~ u1--(_,fl.,C./ cU!.,t,, u,_a,1,,~{a"-~ t L, Lt j-/ (y ~'--? L--y- a~ c/4-.t 7l~ ~~ -zup /r,//~//TJJUJ4y. a.&~ ,,l E kr1J-&1 1}U, ~L-U~ l 6-vl- ~-u _ r <,~ ?:~~L ~ I ~-{lu-,1 7~ _..l~ i allll :i1tft r~,~UL,vtA-, %tt. cz· -t~I;"'~::- /, ~ • I / CJf:z,-61 M, ~u_, PREFACE. IT was predicted of the Great Philanthropist, "He shall tum the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the hearts of children to their fathers." The writer seeks to contribute something toward the development of such mutual afiection between the members of the Pope Family. He has found his own heart tenderly drawn toward all whose names he has registered and whose biographies he has at tempted to write. The dead are his own, whose graves he has sought to strew with the tributes of love ; the living are his own, every one of whose careers he now watches with strong interest. He has given a large part of bis recreation hours and vacation time for eight years to the gathering of materials for the work ; written hundreds of letters ; examined a great many deeds and wills, town journals, church registers, and family records ; visited numerous persons and places, and pored over a large number of histories of towns and families ; and has gathered here the items and entries thus discovered. -

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOSEVELT, THEODORE 1858-1919 Gift of Paul C. Richards, 1976-1990; 1993 Note: Items found in Richards-Roosevelt Room Case are identified as such with the notation ‘[Richards-Roosevelt Room]’. Boxes 1-12 I. Correspondence Correspondence is listed alphabetically but filed chronologically in Boxes 1-11 as noted below. Material filed in Box 12 is noted as such with the notation “(Box 12)”. Box 1 Undated materials and 1881-1893 Box 2 1894-1897 Box 3 1898-1900 Box 4 1901-1903 Box 5 1904-1905 Box 6 1906-1907 Box 7 1908-1909 Box 8 1910 Box 9 1911-1912 Box 10 1913-1915 Box 11 1916-1918 Box 12 TR’s Family’s Personal and Business Correspondence, and letters about TR post- January 6th, 1919 (TR’s death). A. From TR Abbott, Ernest H[amlin] TLS, Feb. 3, 1915 (New York), 1 p. Abbott, Lawrence F[raser] TLS, July 14, 1908 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. ALS, Dec. 2, 1909 (on safari), 4 p. TLS, May 4, 1916 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. TLS, March 15, 1917 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. Abbott, Rev. Dr. Lyman TLS, June 19, 1903 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Nov. 21, 1904 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Feb. 15, 1909 (Washington, D.C.), 2 p. Aberdeen, Lady ALS, Jan. 14, 1918 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. Ackerman, Ernest R. TLS, Nov. 1, 1907 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. Addison, James T[hayer] TLS, Dec. 7, 1915 (Oyster Bay), 1p. Adee, Alvey A[ugustus] TLS, Oct. -

Samuel T. Hauser and Hydroelectric Development on the Missouri River, 1898--1912

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1979 Victim of monopoly| Samuel T. Hauser and hydroelectric development on the Missouri River, 1898--1912 Alan S. Newell The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Newell, Alan S., "Victim of monopoly| Samuel T. Hauser and hydroelectric development on the Missouri River, 1898--1912" (1979). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4013. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4013 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUB SISTS. ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD LIBRARY 7' UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE: 1979 A VICTIM OF MONOPOLY: SAMUEL T. HAUSER AND HYDROELECTRIC DEVELOPMENT ON THE MISSOURI RIVER, 1898-1912 By Alan S. Newell B.A., University of Montana, 1970 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1979 Approved by: VuOiAxi Chairman,lairman, Board of Examiners De^n, Graduate SctooI /A- 7*? Date UMI Number: EP36398 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

1894. Congressional Record-House. 3025

1894. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. 3025 do not want to make any comparison on that line, but it seems ject was to reduce the expenditures of the @fficeforce. I believe to me that an expression of that sort is unparliamentary, unbe there are too many people there. For inst:mce, the Blue Book coming: and entirely out of place. That is parliamentary lan shows that there were as many as 11 messengers employed at· guage\ is it not? There is another set on that sjdeof the House, one time in that office. I thought that the Secretary of the radiating out from the gentleman from Maine-- Treasury, in connection with the Superintendent of the Coast A ME~ER. What do you mean by a ' 'set"? and Geodetic Survey, might rearrange the force of this Bureau Mr. STOCKDALE. Well,anothercorps; thatisbatter. The so as to redt: ce the cost $113 ,600. That was my only purpose. gentleman from Maine, when he r ises to speak, stands over Mr. DINGLEY. I have no doubt that the purpose of the there, looks over to this side of the House and says: '' Let us do chairman of the committee in this matter was exactly as he has this by the rules of common sense," a.ll the time insisting ths.t shted; but my inquiry was as to what the effect might b.e; the Democratic side of this House are without knowledge on the whether this legislation might not go much further than the ~ubject. And then some smaller men will rise and say that we chairman had in tended it should go. -

AHA Colloquium

Cover.indd 1 13/10/20 12:51 AM Thank you to our generous sponsors: Platinum Gold Bronze Cover2.indd 1 19/10/20 9:42 PM 2021 Annual Meeting Program Program Editorial Staff Debbie Ann Doyle, Editor and Meetings Manager With assistance from Victor Medina Del Toro, Liz Townsend, and Laura Ansley Program Book 2021_FM.indd 1 26/10/20 8:59 PM 400 A Street SE Washington, DC 20003-3889 202-544-2422 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.historians.org Perspectives: historians.org/perspectives Facebook: facebook.com/AHAhistorians Twitter: @AHAHistorians 2020 Elected Officers President: Mary Lindemann, University of Miami Past President: John R. McNeill, Georgetown University President-elect: Jacqueline Jones, University of Texas at Austin Vice President, Professional Division: Rita Chin, University of Michigan (2023) Vice President, Research Division: Sophia Rosenfeld, University of Pennsylvania (2021) Vice President, Teaching Division: Laura McEnaney, Whittier College (2022) 2020 Elected Councilors Research Division: Melissa Bokovoy, University of New Mexico (2021) Christopher R. Boyer, Northern Arizona University (2022) Sara Georgini, Massachusetts Historical Society (2023) Teaching Division: Craig Perrier, Fairfax County Public Schools Mary Lindemann (2021) Professor of History Alexandra Hui, Mississippi State University (2022) University of Miami Shannon Bontrager, Georgia Highlands College (2023) President of the American Historical Association Professional Division: Mary Elliott, Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (2021) Nerina Rustomji, St. John’s University (2022) Reginald K. Ellis, Florida A&M University (2023) At Large: Sarah Mellors, Missouri State University (2021) 2020 Appointed Officers Executive Director: James Grossman AHR Editor: Alex Lichtenstein, Indiana University, Bloomington Treasurer: William F. -

Bushnell Family Genealogy, 1945

BUSHNELL FAMILY GENEALOGY Ancestry and Posterity of FRANCIS BUSHNELL (1580 - 1646) of Horsham, England And Guilford, Connecticut Including Genealogical Notes of other Bushnell Families, whose connections with this branch of the family tree have not been determined. Compiled and written by George Eleazer Bushnell Nashville, Tennessee 1945 Bushnell Genealogy 1 The sudden and untimely death of the family historian, George Eleazer Bushnell, of Nashville, Tennessee, who devoted so many years to the completion of this work, necessitated a complete change in its publication plans and we were required to start anew without familiarity with his painstaking work and vast acquaintance amongst the members of the family. His manuscript, while well arranged, was not yet ready for printing. It has therefore been copied, recopied and edited, However, despite every effort, prepublication funds have not been secured to produce the kind of a book we desire and which Mr. Bushnell's painstaking work deserves. His material is too valuable to be lost in some library's manuscript collection. It is a faithful record of the Bushnell family, more complete than anyone could have anticipated. Time is running out and we have reluctantly decided to make the best use of available funds by producing the "book" by a process of photographic reproduction of the typewritten pages of the revised and edited manuscript. The only deviation from the original consists in slight rearrangement, minor corrections, additional indexing and numbering. We are proud to thus assist in the compiler's labor of love. We are most grateful to those prepublication subscribers listed below, whose faith and patience helped make George Eleazer Bushnell's book thus available to the Bushnell Family. -

Director's Letter

DIRECTOR'S LETTER 01 02 MAY 2016 We are proud to be the recipients of the New York Landmarks Conservancy’s prestigious Lucy G. Moses Award for historical DEAR COOPER HEWITT preservation in recognition of our thoughtful renovation and restoration of the mansion. To toast our fortieth anniversary FRIENDS, in the mansion and to celebrate the visionary leadership and support of Cooper Hewitt board members, an elegant garden party is planned for June 8. Details for the event are on page Since our doors opened in 1976 at the Carnegie 20 and I do hope you can join us. I am also very pleased to Mansion, there has been no shortage of beautiful welcome Bart Friedman, Partner, Cahill Gordon & Reindel, and Alain Bernard, President and CEO, Americas, Van Cleef & Arpels, design in Cooper Hewitt’s galleries, and this to Cooper Hewitt’s Board of Trustees—a constant source of spring is no exception. From Beauty, our fifth inspiration and support. Design Triennial, to stunning and iconic works Taking full advantage of summer’s longer days, the museum of modern design from the George R. Kravis II will offer a slew of public programming in the garden for visitors collection, to the iridescent Tiffany glass this season. June 16, we kick off Cocktails at Cooper Hewitt, displayed in our Teak Room, the museum is which this year will include performances by some of New York’s most exciting dance companies and music ensembles. Three showcasing design in all its glory. Outside, of these evenings will feature the famed Juilliard School and, the Arthur Ross Terrace and Garden is bursting in conjunction with our neighbor, The Jewish Museum, and its with new blooms, colors, and textures. -

A Prehistory of the Exclusive Right of Public Performance for Musical Compositions * Zvi S

ROSEN THE TWILIGHT OF THE OPERA PIRATES: A PREHISTORY OF THE EXCLUSIVE RIGHT OF PUBLIC PERFORMANCE FOR MUSICAL COMPOSITIONS * ZVI S. ROSEN I. THE INGERSOLL COPYRIGHT BILL ........................................ 1161 A. The Original Bill .......................................................... 1163 B. The Amended Bill ......................................................... 1165 II. THE MIKADO LITIGATION AND ITS ANTECEDENTS ................ 1168 A. Pre-Mikado Litigation .................................................. 1170 B. The Mikado Litigation.................................................. 1174 III. THE TRELOAR COPYRIGHT BILL ........................................... 1179 A. Opposition from the Copyright Leagues ...................... 1181 B. Pike County Copyright ................................................. 1186 C. The Second Hearing ..................................................... 1188 B. Further Opposition ....................................................... 1191 E. The Committee’s Inaction ............................................ 1194 F. The Music Publishers ................................................... 1197 IV. THE CUMMINGS COPYRIGHT BILL ........................................ 1199 A. Problems with the Existing Dramatic Law ................... 1199 B. The 53rd Congress ....................................................... 1201 C. The 54th Congress, 1st Session .................................... 1205 D. The 54th Congress, 2nd Session—Victory ................... 1210 V. CONCLUSION—THE ROAD