Maryland Historical Magazine, 1919, Volume 14, Issue No. 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

Cemetery Names Master .Xlsx

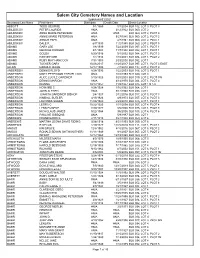

Salem City Cemetery Names and Location Updated 6/01/2021 Deceased Last Name First Name Birthdate Death Date Grave Location ABBOTT TODD GEORGE 3/1/1969 5/1/2004BLK 102, LOT 3, PLOT 3 ABILDSCOV PETER LAURIDS #N/A 6/12/1922BLK 060, LOT 2 ABILDSKOV ANNA MARIE PETERSON #N/A #N/A BLK 060, LOT 2, PLOT 4 ABILDSKOV ANNIE MARIE PETERSON #N/A 9/27/1985BLK 060, LOT 2, PLOT 2 ABILDSKOV ASMUS PAPE #N/A 4/7/1981BLK 060, LOT 2, PLOT 1 ABILDSKOV DALE P. 6/7/1933 11/2/1985BLK 060, LOT 2, PLOT 5 ADAMS GARY LEE 1/8/1939 7/22/2009BLK 097, LOT 1, PLOT 1 ADAMS GEORGE RUDGER 8/1/1903 11/7/1980BLK 092, LOT 1, PLOT 1 ADAMS GOLDA 6/20/1916 9/1/2002BLK 084, LOT 1, PLOT 3 ADAMS HARVEY DEE 1/1/1914 1/10/2001BLK 084, LOT 1, PLOT 2 ADAMS RUBY MAY HANCOCK 7/31/1905 2/29/2000BLK 092, LOT 1 ADAMS TUCKER GARY 10/26/2017 11/20/2017BLK 097, LOT 1, PLOT 3 EAST ALLEN HAROLD JESSE 12/17/1993 7/7/2010BLK 137, LOT 2, PLOT 4 ANDERSEN DENNIS FLOYD 8/28/1936 1/22/2003BLK 016, LOT 3, PLOT 1 ANDERSEN MARY PETERSON TREMELLING #N/A 1/10/1953BLK 040, LOT 3 ANDERSON ALICE LUCILE GARDNER 5/10/1923 5/25/2003BLK 019, LOT 2, PLOT 3W ANDERSON DENNIS MARION #N/A 4/14/1970BLK 084, LOT 1, PLOT 4 ANDERSON DIANNA 10/17/1957 11/9/1957BLK 075, LOT 1 N 1/2 ANDERSON HOWARD C. -

1823 Journal of General Convention

Journal of the Proceedings of the Bishops, Clergy, and Laity of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America in a General Convention 1823 Digital Copyright Notice Copyright 2017. The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America / The Archives of the Episcopal Church All rights reserved. Limited reproduction of excerpts of this is permitted for personal research and educational activities. Systematic or multiple copy reproduction; electronic retransmission or redistribution; print or electronic duplication of any material for a fee or for commercial purposes; altering or recompiling any contents of this document for electronic re-display, and all other re-publication that does not qualify as fair use are not permitted without prior written permission. Send written requests for permission to re-publish to: Rights and Permissions Office The Archives of the Episcopal Church 606 Rathervue Place P.O. Box 2247 Austin, Texas 78768 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 512-472-6816 Fax: 512-480-0437 JOURNAL .. MTRJI OJr TllII "BISHOPS, CLERGY, AND LAITY O~ TIU; PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCH XII TIIJ! UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Xif A GENERAL CONVENTION, Held in St. l'eter's Church, in the City of Philadelphia, from the 20th t" .the 26th Day of May inclusive, A. D. 1823. NEW· YORK ~ PlllNTED BY T. lit J. SWURDS: No. 99 Pearl-street, 1823. The Right Rev. William White, D. D. of Pennsylvania, Pre siding Bishop; The Right Rev. John Henry Hobart, D. D. of New-York, The Right Rev. Alexander Viets Griswold, D. D. of the Eastern Diocese, comprising the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusct ts, Vermont, and Rhode Island, The Right Rev. -

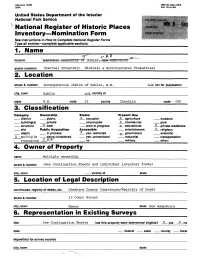

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ' National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name H historic DUBLIN r-Offl and/or common (Partial Inventory; Historic & Architectural Properties) street & number Incorporation limits of Dublin, N.H. n/W not for publication city, town Dublin n/a vicinity of state N.H. code 33 county Cheshire code 005 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public , X occupied X agriculture museum building(s) private -_ unoccupied x commercial park structure x both work in progress X educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object in process x yes: restricted X government scientific X multiple being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation resources X N/A" no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple ownership street & number (-See Continuation Sheets and individual inventory forms) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Cheshire County Courthouse/Registry of Deeds street & number 12 Court Street city, town Keene state New Hampshire 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheets has this property been determined eligible? _X_ yes _JL no date state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description N/A: See Accompanying Documentation. Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered __ original site _ggj|ood £ __ ruins __ altered __ moved date _1_ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance jf Introductory Note The ensuing descriptive statement includes a full exposition of the information requested in the Interim Guidelines, though not in the precise order in which. -

15Th Annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration, SUNY Buffalo State

I II III III I I I I I I I I 15th Annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration, SUNY Buffalo State I II III III I I I I I I I I Editor Jill K. Singer, Ph.D. Director, Office of Undergraduate Research Sponsored by Office of Undergraduate Research Office of Academic Affairs Research Foundation for SUNY/Buffalo State Cover Design and Layout: Carol Alex The following individuals and offices are acknowledged for their many contributions: Sean Fox, Ellofex, Inc. Tom Coates, Events Management, and staff, especially Maryruth Glogowski, Director, E.H. Butler Library, Mary Beth Wojtaszek and the library staff Department and Program Coordinators (identified below) Carole Schaus, Office of Undergraduate Research Kaylene Waite, Computer Graphics Specialist and very special thanks to Carol Alex, Center for Bruce Fox, Photographer Development of Human Services Department and Program Coordinators for the Fifteenth Annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration Lisa Anselmi, Anthropology Bill Lin, Computer Information Systems Kyeonghi Baek, Political Science Dan MacIsaac, Physics Saziye Bayram, Mathematics Candace Masters, Art Education Carol Beckley, Theater Amy McMillan, Biology Lynn Boorady, Fashion and Textile Technology Susan McMillen, Faculty Development Betty Cappella, Higher Education Administration Michaelene Meger, Exceptional Education Louis Colca, Social Work Michael Niman, Communication Michael Cretacci, Criminal Justice Jill Norvilitis, Psychology Carol DeNysschen, Dietetics and Nutrition Kathleen O’Brien, Hospitality and Tourism -

Dorchester Pope Family

A HISTORY OF THE Dorchester Pope Family. 1634-1888. WITH SKETCHES OF OTHER POPES IN ENGLAND AND AMERICA, AND NOTES UPON SEVERAL INTERMARRYING FAMILIES, 0 CHARLES HENRY POPE, MllMBIUl N. E. HISTOalC GENIIALOGlCAl. SOCIETY. BOSTON~ MASS.: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR, AT 79 FRANKLIN ST. 1888 PRESS OF L. BARTA & Co., BOSTON. BOSTON, MA88,,.... (~£P."/.,.. .w.;,.!' .. 190 L.. - f!cynduLdc ;-~,,__ a.ut ,,,,-Mrs. 0 ~. I - j)tt'"rrz-J (i'VU ;-k.Lf!· le a, ~ u1--(_,fl.,C./ cU!.,t,, u,_a,1,,~{a"-~ t L, Lt j-/ (y ~'--? L--y- a~ c/4-.t 7l~ ~~ -zup /r,//~//TJJUJ4y. a.&~ ,,l E kr1J-&1 1}U, ~L-U~ l 6-vl- ~-u _ r <,~ ?:~~L ~ I ~-{lu-,1 7~ _..l~ i allll :i1tft r~,~UL,vtA-, %tt. cz· -t~I;"'~::- /, ~ • I / CJf:z,-61 M, ~u_, PREFACE. IT was predicted of the Great Philanthropist, "He shall tum the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the hearts of children to their fathers." The writer seeks to contribute something toward the development of such mutual afiection between the members of the Pope Family. He has found his own heart tenderly drawn toward all whose names he has registered and whose biographies he has at tempted to write. The dead are his own, whose graves he has sought to strew with the tributes of love ; the living are his own, every one of whose careers he now watches with strong interest. He has given a large part of bis recreation hours and vacation time for eight years to the gathering of materials for the work ; written hundreds of letters ; examined a great many deeds and wills, town journals, church registers, and family records ; visited numerous persons and places, and pored over a large number of histories of towns and families ; and has gathered here the items and entries thus discovered. -

Francis I. W. Jones Treason and Piracy in Civil War Halifax: the Second Chesapeake Affair Revisited "A Terrible Retribution

Francis I. W. Jones Treason And Piracy In Civil War Halifax: The Second Chesapeake Affair Revisited "A terrible retribution awaits the city of Halifax for its complicity in treason and piracy." From the diary of Rev. N. Gunnison Reverend Nathaniel Gunnison, American Consul at Halifax, wrote to Sir Charles Tupper, provincial secretary of Nova Scotia, 10 December 1863, stating that the Chesapeake "had been seized by a band of pirates and murder committed" (Doyle to Newcastle 23 Dec. 1863; Lieut. Governor's Correspondence, RG 1). 1 The Chesapeake was an American steamer plying between New York and Portland, Maine, which had been captured by a party of sixteen men, led by John C. Braine, who had embarked as passengers at New York. After a foray into the Bay of Fundy and along the south shore of Nova Scotia, the Chesapeake was boarded and captured by a United States gunboat the Ella and Annie in Sambro Harbor fourteen miles from Halifax. She was subsequently towed into Halifax and turned over to local authorities after much diplomatic burly burly (Admiralty Papers 777). The affair raised several interesting points of international maritime law, resulted in three trials before the issues raised by the steamer's seizure, recapture and disposition were resolved and was the genesis of several myths and local legends. It not only provided Halifax with "the most exciting Christmas Week in her history" TREASON AND PIRACY IN CIVIL WAR HALIFAX 473 (McDonald 602), it posed the "most thorny diplomatic problem of the Civil War" (Overholtzer 34)? The story of the capture and recapture of the Chesapeake has been told several times with varying degrees of accuracy. -

The Chesapeake Affair Nick Mann

58 Western Illinois Historical Review © 2011 Vol. III, Spring 2011 ISSN 2153-1714 Sailors Board Me Now: The Chesapeake Affair Nick Mann In exploring the origins of the War of 1812, many historians view the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe as the final breaking point in diplomatic relations between the United States and Great Britain. While the clash at Tippecanoe was a serious blow to peace between the two nations, Anglo-American relations had already been ruptured well before the presidency of James Madison. Indian affairs certainly played a role in starting the war, but it was at sea where the core problems lay. I will argue in this essay that rather than the Battle of Tippecanoe, it was the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair of 1807 that set Great Britain and the United States on the path towards war. The affair signified two of the festering issues facing the British and Americans: impressment and neutral rights. Though President Jefferson was able to prevent war in 1807, his administration‟s inept diplomacy widened the existing gap between Britain and America. On both sides of the Atlantic, the inability of leaders such as Secretary of State Madison and the British foreign minister, George Canning to resolve the affair poisoned diplomatic relations for years afterward. To understand the origin of the War of 1812, one must consider how the Chesapeake affair deteriorated Anglo-American relations to a degree that the Battle of Tippecanoe was less important that some have imagined. The clash at Tippecanoe between Governor William Henry Harrison and the forces of the Shawnee Prophet has usually been seen as the direct catalyst for the war in much of the historiography dealing with the War of 1812. -

Maryland Historical Magazine Patricia Dockman Anderson, Editor Matthew Hetrick, Associate Editor Christopher T

Winter 2014 MARYLAND Ma Keeping the Faith: The Catholic Context and Content of ry la Justus Engelhardt Kühn’s Portrait of Eleanor Darnall, ca. 1710 nd Historical Magazine by Elisabeth L. Roark Hi st or James Madison, the War of 1812, and the Paradox of a ic al Republican Presidency Ma by Jeff Broadwater gazine Garitee v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore: A Gilded Age Debate on the Role and Limits of Local Government by James Risk and Kevin Attridge Research Notes & Maryland Miscellany Old Defenders: The Intermediate Men, by James H. Neill and Oleg Panczenko Index to Volume 109 Vo l. 109, No . 4, Wi nt er 2014 The Journal of the Maryland Historical Society Friends of the Press of the Maryland Historical Society The Maryland Historical Society continues its commitment to publish the finest new work in Maryland history. Next year, 2015, marks ten years since the Publications Committee, with the advice and support of the development staff, launched the Friends of the Press, an effort dedicated to raising money to be used solely for bringing new titles into print. The society is particularly grateful to H. Thomas Howell, past committee chair, for his unwavering support of our work and for his exemplary generosity. The committee is pleased to announce two new titles funded through the Friends of the Press. Rebecca Seib and Helen C. Rountree’s forthcoming Indians of Southern Maryland, offers a highly readable account of the culture and history of Maryland’s native people, from prehistory to the early twenty-first century. The authors, both cultural anthropologists with training in history, have written an objective, reliable source for the general public, modern Maryland Indians, schoolteachers, and scholars. -

The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act

Volume 104 Issue 2 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 104, 1999-2000 1-1-2000 The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act Mark R. Shulman Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Mark R. Shulman, The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act, 104 DICK. L. REV. 289 (2000). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol104/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act Mark R. Shulman* Perhaps it is a universal truth that the loss of liberty at home is to be charged to provisions against danger; real or pretended, from abroad. -James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, May 1798' I. Introduction to "National Security" The National Security Act of 19472 and its successors drew the blueprint of the Cold War domestic political order. This regime centralized control of the military services-the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and a newly separate Air Force-in a single executive branch department. It created a new professional organization to collect and analyze foreign intelligence, the Central Intelligence Agency. And at the center of this new national security apparatus, a National Security Council would eventually establish foreign policy by coordinating intelligence and directing military and para-military forces, as well as supervising a National Security Resources Board. -

1789 Journal of Convention

Journal of a Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the States of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina 1789 Digital Copyright Notice Copyright 2017. The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America / The Archives of the Episcopal Church All rights reserved. Limited reproduction of excerpts of this is permitted for personal research and educational activities. Systematic or multiple copy reproduction; electronic retransmission or redistribution; print or electronic duplication of any material for a fee or for commercial purposes; altering or recompiling any contents of this document for electronic re-display, and all other re-publication that does not qualify as fair use are not permitted without prior written permission. Send written requests for permission to re-publish to: Rights and Permissions Office The Archives of the Episcopal Church 606 Rathervue Place P.O. Box 2247 Austin, Texas 78768 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 512-472-6816 Fax: 512-480-0437 JOURNAL OF A. OF THB PROTESTA:N.T EPISCOPAL CHURCH, IN THE STATES OF NEW YORK, MARYLAND, NEW JERSEY, VIRGINIA, PENNSYLVANIA, AND DELAWARE, I SOUTH CAROLINA: HELD IN CHRIST CHURCH, IN THE CITY OF PHILIlDELPBI.IJ, FROM July 28th to August 8th, 178~o LIST OF THE MEMBER5 OF THE CONVENTION. THE Right Rev. William White, D. D. Bishop of the Pro testant Episcopal Church in the State of Pennsylvania, and Pre sident of the Convention. From the State ofNew TorR. The Rev. Abraham Beach, D. D. The Rev. Benjamin Moore, D. D. lIT. Moses Rogers. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1942, Volume 37, Issue No. 3

G ^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. XXXVII SEPTEMBER, 1942 No. } BARBARA FRIETSCHIE By DOROTHY MACKAY QUYNN and WILLIAM ROGERS QUYNN In October, 1863, the Atlantic Monthly published Whittier's ballad, "' Barbara Frietchie." Almost immediately a controversy arose about the truth of the poet's version of the story. As the years passed, the controversy became more involved until every period and phase of the heroine's life were included. This paper attempts to separate fact from fiction, and to study the growth of the legend concerning the life of Mrs. John Casper Frietschie, nee Barbara Hauer, known to the world as Barbara Fritchie. I. THE HEROINE AND HER FAMILY On September 30, 1754, the ship Neptune arrived in Phila- delphia with its cargo of " 400 souls," among them Johann Niklaus Hauer. The immigrants, who came from the " Palatinate, Darmstad and Zweybrecht" 1 went to the Court House, where they took the oath of allegiance to the British Crown, Hauer being among those sufficiently literate to sign his name, instead of making his mark.2 Niklaus Hauer and his wife, Catherine, came from the Pala- tinate.3 The only source for his birthplace is the family Bible, in which it is noted that he was born on August 6, 1733, in " Germany in Nassau-Saarbriicken, Dildendorf." 4 This probably 1 Hesse-Darmstadt, and Zweibriicken in the Rhenish Palatinate. 2 Ralph Beaver Strassburger, Pennsylvania German Pioneers (Morristown, Penna.), I (1934), 620, 622, 625; Pennsylvania Colonial Records, IV (Harrisburg, 1851), 306-7; see Appendix I. 8 T. J. C, Williams and Folger McKinsey, History of Frederick County, Maryland (Hagerstown, Md., 1910), II, 1047.