The Roman Index Its Latest Historian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

<1Tnurnrbitt Ml1tnlngirttl Mnut41y

<1tnurnrbitt ml1tnlngirttl mnut41y Continuing Lehre und Wehre (Vol. LXXVI) Magazin fuer Ev.-Luth. Homiletik (Vol. LlV) Theol. Quarterly (1897-1920)-Theol. Monthly (Vol. X) Vol. II July, 1931 No.7 CONTENTS Page DALLMANN, WM.: How Peter Became Pope .... 481 KRETZMANN, P. E.: Die Familie Davids................ 495 MUELLER, J. T.: Introduction to Sacred Theology...... 500 FUERBRINGER, L.: List of Articles Written by Dr.F.Bente 510 KRETZMANN, P. E.: Aramaismen im Neuen Testament 513 KRUEGER, 0.: Predigtstudie ueber 1 Tim. 6, 6-12. .. 520 Dispositionen ueber die von der Synodalkonferenz ange- nommene Serie alttestamentlicher Texte ............... 526 Theological Observer. - Kirchlich-Zeitgeschichtliches. .. 534 Book Revie\v. - Literatur .. _... __ , .. , ..................... 553 I Em Predlger muse nicht allein wBid"" Es ist kein Ding, das die Leute mehr also dass er die Sehafe unterweise, wie bei der Kircha behaelt den.n die gtJtt II aie rechte Ohrleten Bollen eern, Bontiem Predigt. - ApologiB, Art. 8~. aueh daneben den Woelfen wehr"" dass Bie die Schafe nicht angreiien und mit If the trumpet give an uncertain BOund, faleeher Lehre verfuehren und Irrtum ein· who shall prepare himself to the battle f fuehren. - Luther. 1 Cor. ~,8. Published for the Ev. Luth. Synod of Missouri, Ohio, and Other States CONCORDIA PUBLISHING HOUSE, St. Louis, Mo. AhCI1IVr Concordia Theological Monthly VOL. II JULY, 1931 No.7 How Peter Became Pope. VIII. 1650-1929. Alexander VII, 1655-1667. Fabio Ohigi protested as papal nuntius against the peace of Muenster and Osnabrueck, and there upon Pope Innocent X condemned all concessions to Protestants in the Peace of Westphalia. He got Innocent X to condemn the :five propositions of the "Augustines" of J ansenius of Port Royal. -

Download Download

Judaica Librarianship Volume 9 Number 1–2 17-28 12-31-1995 Climbing Benjacob's Ladder: An Evaluation of Vinograd's Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book Roger S. Kohn Library of Congress, Washington, DC, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ajlpublishing.org/jl Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Information Literacy Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Kohn, Roger S.. 1995. "Climbing Benjacob's Ladder: An Evaluation of Vinograd's Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book." Judaica Librarianship 9: 17-28. doi:10.14263/2330-2976.1178. , Association of Jewish Libraries, 30th Annual Convention, Chicago '.! I APPROBATIONS Climbing -Benjacob's Ladder: An Evaluation of Vinograd's Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book* Rogers.Kohn Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA [Vinograd, Yeshayahu. Otsar ha-sefer ha '/vri: reshimat ha-sefarim she :,~yn ,.!>t,n ,~lN •ln,yw, ,,,n:m nidpesu be-ot '/vrit me 11,~y nuo W.!rTlWc,,.non 1ltl'W1 , reshit ha-def us ha- '/vri bi-shenat 229 (1469) 'ad· ""!:nmvr.i ~Yn Ol.!rTn 11,wNitl shenat 623 (186~. :c,~wl,, .(1863) l"!:>111nlW ;y C1469) Yerushalayim: ha-Makhon ,mwmtltl m.nill'~~~ 1l~tln le-bibliyografyah .n"lW1l·i"lW1l memuhshevet, 754-5, c1993-1995]. Vinograd, Yeshayahu. Abstract: The Thesaurus of the Hebrew The foremost French bibliographer of the Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book, by Yeshayahu Vinograd, is re previous generation, Louise-Noelle Malcles viewed in the context of both general (1899-1977), defines the term bibliography Book: Listing of Books bibliography and of general Hebraica thus: printed in Hebrew Letters bibliography. -

Libraries Without Walls

ROGER CHARTIER Libraries WithoutWalls These examples made it possible fora librarianof genius to discoverthe fundamentallaw of the Library.This thinkerobserved thatall the books, no matterhow diversethey might be, are made up of the same elements: the space, the period, the comma, the twenty-twoletters of the alphabet. He also alleged a factwhich travelers have confirmed:In thevast Library there are no twoidentical books. From these two incontrovertiblepremises he deduced that the Libraryis totaland thatits shelves register all the possible combinations of the twenty-oddorthographical symbols (a numberwhich, although vast,is not infinite):in other words,all thatit is given to express,in all languages. Everything:the minutelydetailed historyof the future,the archangels' autobiographies,the faithfulcatalogue of the Library,thousands and thousands of false catalogues,the demonstrationof the fallacyof those catalogues,the demonstrationof the fallacyof the true catalogue, the Gnosticgospel of Basilides, the commentaryon thatgospel, the commentary on the commentaryon thatgospel, the true storyof your death, the translationof all books in all languages, the interpolationsof everybook in all books. When it was proclaimedthat the Librarycontained all books, the firstimpression was one of extravaganthappiness. Jorge Luis Borges' W H E N I T WA S P RO C L AI ME D that the Library contained all books, the firstimpression was extravagant happiness." The dream of a library (in a variety of configurations) that would bring together all accumulated knowledge and all the books ever written can be found throughout the history of Western civiliza- tion. It underlay the constitution of great princely, ecclesiastical, and private "libraries"; it justified a tenacious search for rare books, lost editions, and texts that had disappeared; it commanded architectural projects to construct edifices capable of welcoming the world's memory. -

The “Doctrine of Discovery” and Terra Nullius: a Catholic Response

1 The “Doctrine of Discovery” and Terra Nullius: A Catholic Response The following text considers and repudiates illegitimate concepts and principles used by Europeans to justify the seizure of land previously held by Indigenous Peoples and often identified by the terms Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius. An appendix provides an historical overview of the development of these concepts vis-a-vis Catholic teaching and of their repudiation. The presuppositions behind these concepts also undergirded the deeply regrettable policy of the removal of Indigenous children from their families and cultures in order to place them in residential schools. The text includes commitments which are recommended as a better way of walking together with Indigenous Peoples. Preamble The Truth and Reconciliation process of recent years has helped us to recognize anew the historical abuses perpetrated against Indigenous peoples in our land. We have also listened to and been humbled by courageous testimonies detailing abuse, inhuman treatment, and cultural denigration committed through the residential school system. In this brief note, which is an expression of our determination to collaborate with First Nations, Inuit and Métis in moving forward, and also in part a response to the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we would like to reflect in particular on how land was often seized from its Indigenous inhabitants without their consent or any legal justification. The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB), the Canadian Catholic Aboriginal Council and other Catholic organizations have been reflecting on the concepts of the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius for some time (a more detailed historical analysis is included in the attached Appendix). -

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY the Roman Inquisition and the Crypto

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Peter Akawie Mazur EVANSTON, ILLINOIS June 2008 2 ABSTRACT The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 Peter Akawie Mazur Between 1569 and 1582, the inquisitorial court of the Cardinal Archbishop of Naples undertook a series of trials against a powerful and wealthy group of Spanish immigrants in Naples for judaizing, the practice of Jewish rituals. The immense scale of this campaign and the many complications that resulted render it an exception in comparison to the rest of the judicial activity of the Roman Inquisition during this period. In Naples, judges employed some of the most violent and arbitrary procedures during the very years in which the Roman Inquisition was being remodeled into a more precise judicial system and exchanging the heavy handed methods used to eradicate Protestantism from Italy for more subtle techniques of control. The history of the Neapolitan campaign sheds new light on the history of the Roman Inquisition during the period of its greatest influence over Italian life. Though the tribunal took a place among the premier judicial institutions operating in sixteenth century Europe for its ability to dispense disinterested and objective justice, the chaotic Neapolitan campaign shows that not even a tribunal bearing all of the hallmarks of a modern judicial system-- a professionalized corps of officials, a standardized code of practice, a centralized structure of command, and attention to the rights of defendants-- could remain immune to the strong privatizing tendencies that undermined its ideals. -

History of the Christian Church*

a Grace Notes course History of the Christian Church VOLUME 6 The Middle Ages, the Decline of the Papacy and the Preparation for Modern Christianity from Boniface VIII to the Reformation, AD 1294 to 1517 By Philip Schaff CH607 Chapter 7: Heresy and Witchcraft History of the Christian Church Volume 6 The Middle Ages, the Decline of the Papacy and the Preparation for Modern Christianity from Boniface VIII to the Reformation, AD 1294 to 1517 CH607 Table of Contents Chapter 7. Heresy and Witchcraft .................................................................................................2 6.57. Literature ................................................................................................................................... 2 6.58. Heretical and Unchurchly Movements ...................................................................................... 3 6.59. Witchcraft and its Punishment ................................................................................................ 11 6.60. The Spanish Inquisition ............................................................................................................ 19 DELRIO: Disquisitiones magicae, Antwerp, 1599, Chapter 7. Heresy and Witchcraft Cologne, 1679.—ERASTUS, of Heidelberg: 6.57. Literature Repititio disputationis de lamiis seu strigibus, Basel, 1578.—J. GLANVILL: Sadducismus For 6.58.—For the BRETHREN OF THE FREE SPIRIT, triumphatus, London, 1681.—R. BAXTER: FREDERICQ: Corpus doc. haer. pravitalis, etc., Certainty of the World of Spirits, London, vols. -

What's the Difference? a Comparison of the Faiths Men Live By

What’s the Difference? A Comparison of the Faiths Men Live By return to religion-online 62 What’s the Difference? A Comparison of the Faiths Men Live By by Louis Cassels Louis Cassels was for many years the religion editor of United Press International. His column "Religion in America" appeared in over four hundred newspapers during the mid-nineteenth century. What’s the Difference was published in 1965 by Doubleday & Company, Inc. This book was prepared for Religion Online by Harry W. and Grace C. Adams. (ENTIRE BOOK) Cassels provides a useful guide to understanding the beliefs and unique characteristics of the different religious groups in the United States. Forward Coming from a background of religion editor of United Press International as well as a committed Protestant Christian, the author proposes to present the distinguishing beliefs of the varying theistic religions with emphasis on Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Chapter 1: The Varieties of Faith An outline of the rudimentary beliefs of atheists, hedonists, humanists, materialists (communists), pantheists, animists, polytheists and monotheists. Chapter 2: The Jewish-Christian Heritage The survival of the Jews as a self-conscious entity for forty centuries – twenty of them in often bitter estrangement from Christianity – is a historical mystery, and deserves careful analysis of the evolution of Semitic monotheism both in the Jewish understanding of covenant, Torah, messiah and obedience as well as Christian concepts of new covenant, atonement, sin and grace. Chapter 3: The Catholic-Protestant Differences Although Catholics and Protestants have been moving cautiously toward each other, real minor and major differences still separate them, including their understandings and interpretations of grace, faith, authority in governance and teaching as it relates to scripture, the role of Mary, and the sacraments. -

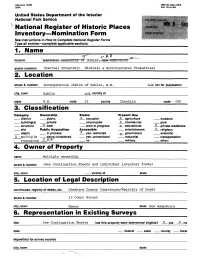

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ' National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name H historic DUBLIN r-Offl and/or common (Partial Inventory; Historic & Architectural Properties) street & number Incorporation limits of Dublin, N.H. n/W not for publication city, town Dublin n/a vicinity of state N.H. code 33 county Cheshire code 005 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public , X occupied X agriculture museum building(s) private -_ unoccupied x commercial park structure x both work in progress X educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object in process x yes: restricted X government scientific X multiple being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation resources X N/A" no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple ownership street & number (-See Continuation Sheets and individual inventory forms) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Cheshire County Courthouse/Registry of Deeds street & number 12 Court Street city, town Keene state New Hampshire 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheets has this property been determined eligible? _X_ yes _JL no date state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description N/A: See Accompanying Documentation. Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered __ original site _ggj|ood £ __ ruins __ altered __ moved date _1_ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance jf Introductory Note The ensuing descriptive statement includes a full exposition of the information requested in the Interim Guidelines, though not in the precise order in which. -

Christopher White Table of Contents

Christopher White Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Peter the “rock”? ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Churches change over time ...................................................................................................................... 6 The Church and her earthly pilgrimage .................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1 The Apostle Peter (d. 64?) : First Bishop and Pope of Rome? .................................................. 11 Peter in Rome ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Yes and No .............................................................................................................................................. 13 The death of Peter .................................................................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2 Pope Sylvester (314-335): Constantine’s Pope ......................................................................... 16 Constantine and his imprint .................................................................................................................... 17 “Remembering” Sylvester ...................................................................................................................... -

Dorchester Pope Family

A HISTORY OF THE Dorchester Pope Family. 1634-1888. WITH SKETCHES OF OTHER POPES IN ENGLAND AND AMERICA, AND NOTES UPON SEVERAL INTERMARRYING FAMILIES, 0 CHARLES HENRY POPE, MllMBIUl N. E. HISTOalC GENIIALOGlCAl. SOCIETY. BOSTON~ MASS.: PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR, AT 79 FRANKLIN ST. 1888 PRESS OF L. BARTA & Co., BOSTON. BOSTON, MA88,,.... (~£P."/.,.. .w.;,.!' .. 190 L.. - f!cynduLdc ;-~,,__ a.ut ,,,,-Mrs. 0 ~. I - j)tt'"rrz-J (i'VU ;-k.Lf!· le a, ~ u1--(_,fl.,C./ cU!.,t,, u,_a,1,,~{a"-~ t L, Lt j-/ (y ~'--? L--y- a~ c/4-.t 7l~ ~~ -zup /r,//~//TJJUJ4y. a.&~ ,,l E kr1J-&1 1}U, ~L-U~ l 6-vl- ~-u _ r <,~ ?:~~L ~ I ~-{lu-,1 7~ _..l~ i allll :i1tft r~,~UL,vtA-, %tt. cz· -t~I;"'~::- /, ~ • I / CJf:z,-61 M, ~u_, PREFACE. IT was predicted of the Great Philanthropist, "He shall tum the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the hearts of children to their fathers." The writer seeks to contribute something toward the development of such mutual afiection between the members of the Pope Family. He has found his own heart tenderly drawn toward all whose names he has registered and whose biographies he has at tempted to write. The dead are his own, whose graves he has sought to strew with the tributes of love ; the living are his own, every one of whose careers he now watches with strong interest. He has given a large part of bis recreation hours and vacation time for eight years to the gathering of materials for the work ; written hundreds of letters ; examined a great many deeds and wills, town journals, church registers, and family records ; visited numerous persons and places, and pored over a large number of histories of towns and families ; and has gathered here the items and entries thus discovered. -

John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Author(S): Catherine O’Donnell Source: the William and Mary Quarterly, Vol

John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Author(s): Catherine O’Donnell Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 1 (January 2011), pp. 101-126 Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5309/willmaryquar.68.1.0101 Accessed: 17-10-2018 15:23 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The William and Mary Quarterly This content downloaded from 134.198.197.121 on Wed, 17 Oct 2018 15:23:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 101 John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Catherine O’Donnell n 1806 Baltimoreans saw ground broken for the first cathedral in the United States. John Carroll, consecrated as the nation’s first Catholic Ibishop in 1790, had commissioned Capitol architect Benjamin Latrobe and worked with him on the building’s design. They planned a neoclassi- cal brick facade and an interior with the cruciform shape, nave, narthex, and chorus of a European cathedral. -

Is the Church Responsible for the Inquisition? Illustrated

IS THE CHURCH RESPONSIBLE FOR THE INQUISITION ? BY THE EDITOR. THE QUESTION has often been raised whether or not the Church is responsible for the crimes of heresy trials, witch prosecutions and the Inquisition, and the answer depends entirely ^k^fcj^^^mmmwj^^ The Banner of the Spanish Inquisition. The Banner o?- the Inouisition of Goa.1 upon our definition of the Church. If we understand by Church the ideal bond that ties all religious souls together in their common aspirations for holiness and righteousness, or the communion of saints, we do not hesitate to say that we must distinguish between IThe illustrations on pages 226-232 are reproduced from Packard. IS THE CHURCH RESPONSIBLE FOR THE INQUISITION? 227 The Chamber of the Inquisition. Tl-V I ' ^1 * y '^u Tj- - i;J\f.4.. 1 T77,. ^*~"- \ \1 II 11 s M WNH s nl- ( ROSS I \ \MININ(, 1 Hh DEFENDANTS. 228 THE OPEN COURl'. if the ideal and its representatives ; but we understand by Church the organisation as it actually existed at the time, there is no escape from holding the Church responsible for everything good and evil done by her plenipotentiaries and authorised leaders. Now, it is strange that while many Roman Catholics do not hesitate to con- cede that many grievous mistakes have been made by the Church, and that the Church has considerably changed not only its policy but its principles, there are others who would insist on defending the most atrocious measures of the Church, be it on the strength of A Man and a Woman Convicted of Heresy who have Pleaded Guilty Before Being Condemned to Death.