NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY the Roman Inquisition and the Crypto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8079K See Change Briefing Paper

CatholicCatholicTheThe ChurchChurch atat thetheUnitedUnited NationsNations Church or ?State? The Catholic It is the world’s smallest “city-state” at 108.7 acres. It houses the infrastructure of the Roman church at the UN: Catholic church: the pope’s palace, St. Peter’s A religion or a state? Basilica, offices and administrative services and libraries and archives.2 Vatican City was created Many questions have been raised about the role in 1929 under a treaty signed between Benito of the Catholic church at the United Nations Mussolini and Pietro Cardinale Gasparri, as a result of its high-profile and controversial secretary of state to Pope Pius XI.The Lateran role at international conferences. Participating Treaty was designed to compensate the pope as a full-fledged state actor in these for the 1870 annexation of the Papal States, conferences, the Holy See often goes against which consisted of 17,218 square miles in the overwhelming consensus of member states central Italy, and to guarantee the “indisputable “The Holy See is and seeks provisions in international documents sovereignty” of the Holy See by granting it a TheThe “See“See Change”Change” that would limit the health and rights of all not a state, but is physical territory.3 According to Archbishop Campaign people, but especially of women. How did the accepted as being Campaign Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, a former Vatican Holy See, the government of the Roman on the same footing Hundreds of organizations and thousands of people diplomat who wrote the authoritative work on Catholic -

Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia

Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Assessorato allo Sviluppo Dipartimento Lavoro e Impresa Servizio Impresa e Sportello Unico per le Attività Produttive BANDO RETI Legge 266/97 - Annualità 2011 Agevolazioni a favore delle piccole imprese e microimprese operanti nei quartieri: Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia, Miano, Secondigliano, San Pietro a Patierno, Ponticelli, Barra, San Giovanni a Teduccio, San Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Stella, San Carlo Arena, Mercato, Pendino, Avvocata, Montecalvario, S.Giuseppe, Porto. Art. 14 della legge 7 agosto 1997, n. 266. Decreto del ministro delle attività produttive 14 settembre 2004, n. 267. Pagina 1 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 SOMMARIO ART. 1 – OBIETTIVI, AMBITO DI APPLICAZIONE E DOTAZIONE FINANZIARIA ART. 2 – REQUISITI DI ACCESSO. ART. 3 – INTERVENTI IMPRENDITORIALI AMMISSIBILI. ART. 4 – TIPOLOGIA E MISURA DEL FINANZIAMENTO ART. 5 – SPESE AMMISSIBILI ART. 6 – VARIAZIONI ALLE SPESE DI PROGETTO ART. 7 – PRESENTAZIONE DOMANDA DI AMMISSIONE ALLE AGEVOLAZIONI ART. 8 – PROCEDURE DI VALUTAZIONE E SELEZIONE ART. 9 – ATTO DI ADESIONE E OBBLIGO ART. 10 – REALIZZAZIONE DELL’INVESTIMENTO ART. 11 – EROGAZIONE DEL CONTRIBUTO ART. 12 –ISPEZIONI, CONTROLLI, ESCLUSIONIE REVOCHE DEI CONTRIBUTI ART. 13 – PROCEDIMENTO AMMINISTRATIVO ART. 14 – TUTELA DELLA PRIVACY ART. 15 – DISPOSIZIONI FINALI Pagina 2 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Art. 1 – Obiettivi, -

Information Guide Vatican City

Information Guide Vatican City A guide to information sources on the Vatican City State and the Holy See. Contents Information sources in the ESO database .......................................................... 2 General information ........................................................................................ 2 Culture and language information..................................................................... 2 Defence and security information ..................................................................... 2 Economic information ..................................................................................... 3 Education information ..................................................................................... 3 Employment information ................................................................................. 3 European policies and relations with the European Union .................................... 3 Geographic information and maps .................................................................... 3 Health information ......................................................................................... 3 Human rights information ................................................................................ 4 Intellectual property information ...................................................................... 4 Justice and home affairs information................................................................. 4 Media information ......................................................................................... -

Jews on Trial: the Papal Inquisition in Modena

1 Jews, Papal Inquisitors and the Estense dukes In 1598, the year that Duke Cesare d’Este (1562–1628) lost Ferrara to Papal forces and moved the capital of his duchy to Modena, the Papal Inquisition in Modena was elevated from vicariate to full Inquisitorial status. Despite initial clashes with the Duke, the Inquisition began to prosecute not only heretics and blasphemers, but also professing Jews. Such a policy towards infidels by an organization appointed to enquire into heresy (inquisitio haereticae pravitatis) was unusual. In order to understand this process this chapter studies the political situation in Modena, the socio-religious predicament of Modenese Jews, how the Roman Inquisition in Modena was established despite ducal restrictions and finally the steps taken by the Holy Office to gain jurisdiction over professing Jews. It argues that in Modena, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Holy Office, directly empowered by popes to try Jews who violated canons, was taking unprecedented judicial actions against them. Modena, a small city on the south side of the Po Valley, seventy miles west of Ferrara in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, originated as the Roman town of Mutina, but after centuries of destruction and renewal it evolved as a market town and as a busy commercial centre of a fertile countryside. It was built around a Romanesque cathedral and the Ghirlandina tower, intersected by canals and cut through by the Via Aemilia, the ancient Roman highway from Piacenza to Rimini. It was part of the duchy ruled by the Este family, who origi- nated in Este, to the south of the Euganean hills, and the territories it ruled at their greatest extent stretched from the Adriatic coast across the Po Valley and up into the Apennines beyond Modena and Reggio, as well as north of the Po into the Polesine region. -

An Educator's Guide To

An Educator’s Guide to by Adam Gidwitz Dear Educator, I’m at the Holy Crossroads Inn, a day’s walk north of Paris. Outside, the sky is dark, and getting darker… It’s the perfect night for a story. Critically acclaimed Adam Gidwitz’s new novel has “as much to say about the present as it does the past.” (— Publishers Weekly). Themes of social justice, tolerance and empathy, and understanding differences, especially as they relate to personal beliefs and religion, run through- out his expertly told tale. The story, told from multiple narrator’s points of view, is evocative of The Canterbury Tales—richly researched and action packed. Ripe for 4th-6th grade learners, it could be read aloud or assigned for at-home or in-school reading. The following pages will guide you through teaching the book. Broken into sections and with suggested links and outside source material to reference, it will hopefully be the starting point for you to incorporate this book into the fabric of your classroom. We are thrilled to introduce you to a new book by Adam, as you have always been great champions of his books. Thank you for your continued support of our books and our brand. Penguin School & Library About the Author: Adam Gidwitz taught in Brooklyn for eight years. Now, he writes full- time—which means he writes a couple of hours a day, and lies on the couch staring at the ceiling the rest of the time. As is the case with all of this books, everything in them not only happened in the real fairy tales, it also happened to him. -

Spiritualidad En La Europa De… Roberto López Vela (Coord.) Paolo IV, Le Riforme Della Curia, Gli “Spirituali”… Giampiero Brunelli

TIEMPOS MODERNOS 37 (2018/2) ISSN:1699-7778 MONOGRÁFICO: Fe y espiritualidad en la Europa de… Roberto López Vela (Coord.) Paolo IV, le riforme della Curia, gli “Spirituali”… Giampiero Brunelli Paolo IV, le riforme della Curia, gli “Spirituali”: interrelazioni, riposizionamenti. Paul IV, the reforms of the Curia, the “Spirituali”: interrelations, repositioning. Giampiero Brunelli Università Telematica San Raffaele (Roma) Resumen: Paulo IV ha sido juzgado por la historiografía de una manera muy negativa, incluso aludiendo a sus obsesiones psicopatológicas, en lugar de hacerlo desde el punto de vista de la historia de las instituciones. El Papa Carafa puede considerarse el «actor principal» de la «institución-Iglesia», quien estableció sus propios objetivos (es decir, una política de reforma peculiar) y que participó en ellos algunos de los llamados «espirituales»: Giovanni Morone, Reginald Pole, Camillo Orsini. Su visión de la Iglesia parece que tuvo consenso en Roma, incluso en 1559, el último año de su pontificado. Palabras clave: Paulo IV; Reforma; Curia romana; “Espirituales”. Abstract: Paul IV has been judged by historiography in a very negative way, even alluding to his psycho-pathological obsessions. Instead, from the point of view of the history of the institutions, Pope Carafa, can be considered as the «top actor» of the «institution-Church», who set himself objectives (i.e. a peculiar reformation polity) and who involved in them some of the so-called «spirituali»: Giovanni Morone, Reginald Pole, Camillo Orsini. His vision of the Church seems to find consensus in Rome, even in 1559, the last year of his pontificate. Keywords: Paul IV; Reformation; Roman Curia; “Spirituali”. -

The Holy See

The Holy See I GENERAL NORMS Notion of Roman Curia Art. 1 — The Roman Curia is the complex of dicasteries and institutes which help the Roman Pontiff in the exercise of his supreme pastoral office for the good and service of the whole Church and of the particular Churches. It thus strengthens the unity of the faith and the communion of the people of God and promotes the mission proper to the Church in the world. Structure of the Dicasteries Art. 2 — § 1. By the word "dicasteries" are understood the Secretariat of State, Congregations, Tribunals, Councils and Offices, namely the Apostolic Camera, the Administration of the Patrimony of the Apostolic See, and the Prefecture for the Economic Affairs of the Holy See. § 2. The dicasteries are juridically equal among themselves. § 3. Among the institutes of the Roman Curia are the Prefecture of the Papal Household and the Office for the Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff. Art. 3 — § 1. Unless they have a different structure in virtue of their specific nature or some special law, the dicasteries are composed of the cardinal prefect or the presiding archbishop, a body of cardinals and of some bishops, assisted by a secretary, consultors, senior administrators, and a suitable number of officials. § 2. According to the specific nature of certain dicasteries, clerics and other faithful can be added to the body of cardinals and bishops. § 3. Strictly speaking, the members of a congregation are the cardinals and the bishops. 2 Art. 4. — The prefect or president acts as moderator of the dicastery, directs it and acts in its name. -

Apostolic Lines of Succession-10-2018

Apostolic Lines of Succession for ++Michael David Callahan, DD, OCR, OCarm. The Catholic Church in America “Have you an apostolic succession? Unfold the line of your bishops.” Tertullian, 3rd century A.D. A special visible expression of Apostolic Succession is given in the consecration/ ordination of a bishop through the laying on of hands by other bishops who have, themselves, been ordained in the same manner through a succession of bishops leading back to the apostles of Jesus. The role of the bishop must always be understood within the context of the authentic handing on of the faith from one generation to the next generation of the whole Church, beginning with the Christian community of the time of the Apostles. Thus, as the Church is the continuation of the apostolic community, so the bishops are the continuation of the ministry of the college of the apostles of Jesus within that apostolic community. It is essentially collegial rather than monarchical. This tradition is affirmed in the teaching ministry of Church leadership, and authentically celebrated in the sacraments, with particular attention to the sacrament of holy orders (ordination) and the laying on of hands. Apostolic Succession is the belief of Catholic Christians that the bishops are successors of the original apostles of Jesus. This is understood as the bishops being ordained into the episcopal collegium or “sacramental order.” As bishops are by tradition consecrated by at least three other bishops, the actual number of lists of succession can become quite substantial. Listed here are three lines of succession: 1. From Saints Paul and Linus Succession through Archbishop Baladad 2. -

Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology After the Holocaust Carolyn Wesnousky Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College History Honors Papers History Department 2012 “Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust Carolyn Wesnousky Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/histhp Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wesnousky, Carolyn, "“Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust" (2012). History Honors Papers. 15. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/histhp/15 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. “Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust An Honors Thesis Presented by Carolyn Wesnousky To The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field Connecticut College New London, Connecticut April 26, 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………...…………..4 Chapter 1: Living in a Christian World......…………………….….……….15 Chapter 2: The Holocaust Comes to Rome…………………...…………….49 Chapter 3: Preparing the Ground for Change………………….…………...68 Chapter 4: Nostra Aetate before the Second Vatican Council……………..95 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………110 Appendix……………………………………………..……………………114 Bibliography………………………………………………………………..117 2 Acknowledgements As much as I would like to claim sole credit for the effort that went into creating this paper, I need to take a moment and thank the people without whom I never would have seen its creation. -

The Mortara Affair and the Question of Thomas Aquinas's Teaching

SCJR 14, no. 1 (2019): 1-18 The Mortara Affair and the Question of Thomas Aquinas’s Teaching Against Forced Baptism MATTHEW TAPIE [email protected] Saint Leo University, Saint Leo, FL 33574 Introduction In January 2018, controversy over the Mortara affair remerged in the United States with the publication of Dominican theologian Romanus Cessario’s essay de- fending Pius IX’s decision to remove Edgardo Mortara, from his home, in Bologna.1 In order to forestall anti-Catholic sentiment in reaction to an upcoming film, Cessario argued that the separation of Edgardo from his Jewish parents is what the current Code of Canon Law, and Thomas Aquinas’s theology of baptism, required.2 For some, the essay damaged Catholic-Jewish relations. Writing in the Jewish Review of Books, the Archbishop of Philadelphia, Charles Chaput, lamented that Cessario’s defense of Pius revived a controversy that has “left a stain on Catholic- Jewish relations for 150 years.” “The Church,” wrote Chaput, “has worked hard for more than 60 years to heal such wounds and repent of past intolerance toward the Jewish community. This did damage to an already difficult effort.”3 In the 1 On June 23rd, 1858, Pope Pius IX ordered police of the Papal States to remove a six-year-old Jewish boy, Edgardo Mortara, from his home, in Bologna, because he had been secretly baptized by his Chris- tian housekeeper after allegedly falling ill. Since the law of the Papal States stipulated that a person baptized must be raised Catholic, Inquisition authorities forcibly removed Edgardo from his parents’ home, and transported him to Rome. -

Is the Church Responsible for the Inquisition? Illustrated

IS THE CHURCH RESPONSIBLE FOR THE INQUISITION ? BY THE EDITOR. THE QUESTION has often been raised whether or not the Church is responsible for the crimes of heresy trials, witch prosecutions and the Inquisition, and the answer depends entirely ^k^fcj^^^mmmwj^^ The Banner of the Spanish Inquisition. The Banner o?- the Inouisition of Goa.1 upon our definition of the Church. If we understand by Church the ideal bond that ties all religious souls together in their common aspirations for holiness and righteousness, or the communion of saints, we do not hesitate to say that we must distinguish between IThe illustrations on pages 226-232 are reproduced from Packard. IS THE CHURCH RESPONSIBLE FOR THE INQUISITION? 227 The Chamber of the Inquisition. Tl-V I ' ^1 * y '^u Tj- - i;J\f.4.. 1 T77,. ^*~"- \ \1 II 11 s M WNH s nl- ( ROSS I \ \MININ(, 1 Hh DEFENDANTS. 228 THE OPEN COURl'. if the ideal and its representatives ; but we understand by Church the organisation as it actually existed at the time, there is no escape from holding the Church responsible for everything good and evil done by her plenipotentiaries and authorised leaders. Now, it is strange that while many Roman Catholics do not hesitate to con- cede that many grievous mistakes have been made by the Church, and that the Church has considerably changed not only its policy but its principles, there are others who would insist on defending the most atrocious measures of the Church, be it on the strength of A Man and a Woman Convicted of Heresy who have Pleaded Guilty Before Being Condemned to Death. -

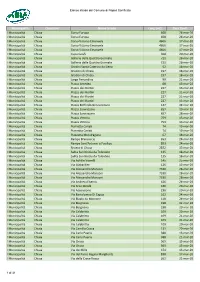

Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(Mt) Data Sanif

Elenco strade del Comune di Napoli Sanificate Municipalità Quartiere Nome Strada Lung.(mt) Data Sanif. I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Europa 608 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Corso Vittorio Emanuele 4606 17-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Cupa Caiafa 368 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Galleria delle Quattro Giornate 721 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradini Santa Caterina da Siena 52 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Gradoni di Chiaia 197 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Largo Ferrandina 99 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Amedeo 68 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 21-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza dei Martiri 227 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Roffredo Beneventano 147 24-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 20-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Sannazzaro 657 28-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazza Vittoria 759 13-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Cariati 74 19-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Piazzetta Mondragone 67 18-mar-20 I Municipalità Chiaia Rampe Brancaccio 653 24-mar-20 I Municipalità