The Premonstratensian Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Striking

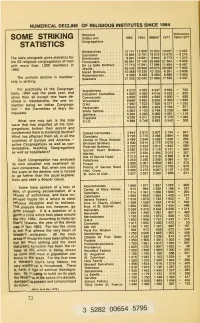

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Being Seen: an Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia J

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College History Honors Projects History Department Spring 4-21-2011 Being Seen: An Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia J. Belote Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/history_honors Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Other Applied Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Belote, Olivia J., "Being Seen: An Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome" (2011). History Honors Projects. Paper 9. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/history_honors/9 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Being Seen: An Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia Joy Belote Honors Project, History 2011 1 History Honors 2011 Advisor: Peter Weisensel Second Readers: Kristin Lanzoni and Susanna Drake Contents Page Introduction..................................................................................................................3 Feminist History and Females in Christianity..............................................................6 The -

SPIRITUALITY: ABCD's “Catholic Spirituality” This Work Is a Study in Catholic Spirituality. Spirituality Is Concerned With

SPIRITUALITY: ABCD’s “Catholic Spirituality” This work is a study in Catholic spirituality. Spirituality is concerned with the human subject in relation to God. Spirituality stresses the relational and the personal though does not neglect the social and political dimensions of a person's relationship to the divine. The distinction between what is to be believed in the do- main of dogmatic theology (the credenda) and what is to be done as a result of such belief in the domain of moral theology (the agenda) is not always clear. Spirituality develops out of moral theology's concern for the agenda of the Christian life of faith. Spirituality covers the domain of religious experience of the divine. It is primarily experiential and practical/existential rather than abstract/academic and conceptual. Six vias or ways are included in this compilation and we shall take a look at each of them in turn, attempting to highlight the main themes and tenets of these six spiritual paths. Augustinian Spirituality: It is probably a necessary tautology to state that Augus- tinian spirituality derives from the life, works and faith of the African Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430). This spirituality is one of conversion to Christ through caritas. One's ultimate home is in God and our hearts are restless until they rest in the joy and intimacy of Father, Son and Spirit. We are made for the eternal Jerusalem. The key word here in our earthly pilgrimage is "conversion" and Augustine describes his own experience of conversion (metanoia) biographically in Books I-IX of his Confessions, a spiritual classic, psychologically in Book X (on Memory), and theologically in Books XI-XIII. -

Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century

A “Truly Unmonastic Way of Life”: Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hannah Elizabeth Ewing Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Timothy Gregory, Advisor Professor Anthony Kaldellis Professor Alison I. Beach Copyright by Hannah Elizabeth Ewing 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines twelfth-century Byzantine writings on monasticism and holy men to illuminate monastic critiques during this period. Drawing upon close readings of texts from a range of twelfth-century voices, it processes both highly biased literary evidence and the limited documentary evidence from the period. In contextualizing the complaints about monks and reforms suggested for monasticism, as found in the writings of the intellectual and administrative elites of the empire, both secular and ecclesiastical, this study shows how monasticism did not fit so well in the world of twelfth-century Byzantium as it did with that of the preceding centuries. This was largely on account of developments in the role and operation of the church and the rise of alternative cultural models that were more critical of traditional ascetic sanctity. This project demonstrates the extent to which twelfth-century Byzantine society and culture had changed since the monastic heyday of the tenth century and contributes toward a deeper understanding of Byzantine monasticism in an under-researched period of the institution. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family, and most especially to my parents. iii Acknowledgments This dissertation is indebted to the assistance, advice, and support given by Anthony Kaldellis, Tim Gregory, and Alison Beach. -

A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (With Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia)

religions Article A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia) Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig Jakobsen Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics, University of Copenhagen, 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] Abstract: Monasticism was introduced to Denmark in the 11th century. Throughout the following five centuries, around 140 monastic houses (depending on how to count them) were established within the Kingdom of Denmark, the Duchy of Schleswig, the Principality of Rügen and the Duchy of Estonia. These houses represented twelve different monastic orders. While some houses were only short lived and others abandoned more or less voluntarily after some generations, the bulk of monastic institutions within Denmark and its related provinces was dissolved as part of the Lutheran Reformation from 1525 to 1537. This chapter provides an introduction to medieval monasticism in Denmark, Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia through presentations of each of the involved orders and their history within the Danish realm. In addition, two subchapters focus on the early introduction of monasticism to the region as well as on the dissolution at the time of the Reformation. Along with the historical presentations themselves, the main and most recent scholarly works on the individual orders and matters are listed. Keywords: monasticism; middle ages; Denmark Citation: Jakobsen, Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig. 2021. A Brief For half a millennium, monasticism was a very important feature in Denmark. From History of Medieval Monasticism in around the middle of the 11th century, when the first monastic-like institutions were Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and introduced, to the middle of the 16th century, when the last monasteries were dissolved Estonia). -

Psalter (Premonstratensian Use) in Latin, Illuminated Manuscript on Parchment, with (Added) Musical Notation Northwestern Germany (Diocese of Cologne), C

Psalter (Premonstratensian use) In Latin, illuminated manuscript on parchment, with (added) musical notation Northwestern Germany (diocese of Cologne), c. 1270-1280 270 folios on parchment, modern foliation in pencil, 1-270, complete (collation i13 [quire of 12 with a singleton added at the end] ii-xx12 xxi10 [-10, cancelled blank after f. 250] xxii-xxiii8 xxiv4), no catchwords or signatures, ruled in brown ink until f. 250 (justification 74 x 47 mm.), written by three different scribes in brown ink in gothic textualis bookhand on 17 lines, originally the manuscript included quires 1-xxi, ff. 1-250, in the early fourteenth century new texts were added on the space left blank on ff. 248v-250v and on the added leaves (not ruled), prickings visible in the outer margins, 2-line initials in red or blue with contrasting penwork flourishing beginning psalms and other texts, twenty- one 3- to 6-line initials in burnished gold on grounds painted in dark pink and blue decorated with white penwork, ONE ILLUMINATED INITIAL, 7-lines, opening the psalms, chants added in the margins in fourteenth-century textualis hand and hufnagelschrift notation, a small tear in the outer margin of f. 173, occasional flaking of the pigment and gold of initials, thumbing, otherwise in excellent condition. Bound in the sixteenth century in calf over wooden boards blind-tooled with a roll with heads in profile, lacking clasps and catches, worn at joints, otherwise in excellent condition. Dimensions 103 x 75 mm. Charming example of an illuminated liturgical Psalter, certainly owned by women in the seventeenth century, and perhaps made for Premonstratensian nuns. -

The Early Privileges of the Society of Jesus 1537 to 1556

Concessions, communications, and controversy: the early privileges of the Society of Jesus 1537 to 1556 Author: Robert Morris Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108457 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2019 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Concessions, Communications and Controversy: The Early Privileges of the Society of Jesus 1537 to 1556. Partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Licentiate in Sacred Theology Robert Morris, S.J. Readers Dr. Catherine M. Mooney Dr. Barton Geger, S.J. Boston College 2019 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE: THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF RELIGIOUS PRIVILEGES ................ 6 ORIGINS: PRIVILEGES IN ROMAN LAW .................................................................................................................. 6 THE PRIVILEGE IN MEDIEVAL CANON LAW ......................................................................................................... 7 Mendicants ........................................................................................................................................................... 12 Developments in the Canon Law of Privileges in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries ... 13 Further distinctions and principles governing privileges ............................................................... -

CARTHUSIAN WORLDS, CARTHUSIAN IMAGES The

Studies in Spirituality 24, 143-154. doi: 10.2143/SIS.24.0.3053494 © 2014 by Studies in Spirituality. All rights reserved. PETER NISSEN CARTHUSIAN WORLDS, CARTHUSIAN IMAGES The Fascination of Silence and Inaccessibility SUMMARY – The silent, hidden world of the Carthusians has become known to a broad public thanks to the 2005 film, Die grosse Stille / Into Great Silence from the German producer Philip Gröning. That world appears to fascinate people, as evidenced by earlier films and books about Carthusian life as well. But the onlooker remains an outsider. Films and books afford a fleeting glimpse of an inside world marked by inaccessi- bility. The inaccessibility in fact accounts for the outsider’s fascination. Usually it results in a biased picture: the Carthusian world is seen as paradisiac. Yet a number of recent autobiographic works by former Carthusians demolish the idyll of the ‘white paradise’. They show that the silent, enclosed world of the Carthusians is marred by acute psycho- logical tensions. These are mainly about boundaries: where does the Carthusian world begin and end, where is the boundary between the inside and the outside world, between the individual monk and the com- munity? The author proposes studying the realities of Carthusian life from the angle of three dialectical relationships: that of the Carthusian and the outside world, of the anchorite and the coenobite (hence the individual monk and the community), and of practical and inner life (the monk’s own inner and outside worlds). 1. INTO GREAT SILENCE – A VISITOR TO A WORLD WITHIN A WORLD Since the autumn of 2005 a lot of people, many of whom had probably never heard of the existence of Carthusians before, have gained access to the Carthu- sian world. -

Naughty Nuns and Promiscuous Monks: Monastic Sexual Misconduct in Late Medieval England

Naughty Nuns and Promiscuous Monks: Monastic Sexual Misconduct in Late Medieval England by Christian D. Knudsen A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of the Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto Copyright © by Christian D. Knudsen ABSTRACT Naughty Nuns and Promiscuous Monks: Monastic Sexual Misconduct in Late Medieval England Christian D. Knudsen Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto This dissertation examines monastic sexual misconduct in cloistered religious houses in the dioceses of Lincoln and Norwich between and . Traditionally, any study of English monasticism during the late Middle Ages entailed the chronicling of a slow decline and decay. Indeed, for nearly years, historiographical discourse surrounding the Dissolution of Monasteries (-) has emphasized its inevitability and presented late medieval monasticism as a lacklustre institution characterized by worsening standards, corruption and even sexual promiscuity. As a result, since the Dissolution, English monks and nuns have been constructed into naughty characters. My study, centred on the sources that led to this claim, episcopal visitation records, will demonstrate that it is an exaggeration due to the distortion in perspective allowed by the same sources, and a disregard for contextualisation and comparison between nuns and monks. In Chapter one, I discuss the development of the monastic ‘decline narrative’ in English historiography and how the theme of monastic lasciviousness came to be so strongly associated with it. Chapter two presents an overview of the historical background of late medieval English monasticism and my methodological approach to the sources. ii Abstract iii In Chapter three, I survey some of the broad characteristics of monastic sexual misconduct. -

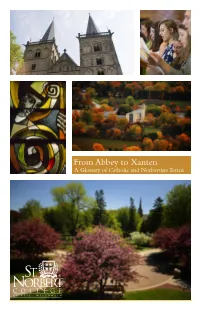

Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms from Abbey to Xanten a Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms

From Abbey to Xanten A Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms From Abbey to Xanten A Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms As part of our mission at St. Norbert College, we value the importance of communio, a centuries-old charism of the Order of Premonstratensians (more commonly known as the Norbertines). Communio is characterized by mutual esteem, trust, sincerity, faith and responsibility, and is lived through open dialogue, communication, consultation and collaboration. In order for everyone to effectively engage in this ongoing dialogue, it is important that we share some of the same vocabulary and understand the concepts that shape our values as an institution. Because the college community is composed of people from diverse faith traditions and spiritual perspectives, this glossary explains a number of terms and concepts from the Catholic and Norbertine traditions with which some may not be familiar. We offer it as a guide to help people avoid those awkward moments one can experience when entering a new community – a place where people can sometimes appear to be speaking in code. While the terms in this modest pamphlet are important, the definitions are limited and are best considered general indications of the meaning of the terms rather than a complete scholarly treatment. We hope you find this useful. If there are other terms or concepts you would like to learn more about that are not covered in this guide, please feel free to contact the associate vice president for mission & student affairs at 920-403-3014 or [email protected]. In the spirit of communio, The Staff of Mission & Student Affairs When a word in a definition appears in bold type, it indicates that the word is defined elsewhere in the glossary. -

Anti Christian Persecutions

Dowry Winter 2020, Issue N˚44 “O Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of God and our most gentle Queen and Mother, look down in mercy upon England thy Dowry.” In this issue: Editorial: Persecution and Resurrection Special issue on For Your Diaries Anti Christian England is Our Lady’s Dowry Persecutions Our ¼ Billion Persecuted Fellow Christians They Did Nothing But Pray Our Lady’s Reconquista Taking Oaths to Ungodly Leaders Meditative Film ‘A Hidden Life’ On Pilgrimage to Italy Concerning Art, Music and Man (Part 1) Support Our Apostolate (N˚41, Spring 2019) Dowry – Catholic periodical by the FSSP in Great Britain & Ireland (N°44, Winter 2020) Editorial: Persecution and Resurrection ur country has left the entrustment. Our personal promise received almost no European Union. It has not brings us closer to Our Lady, the further donations. As explained at O left Europe, though. As first disciple of Christ. In this we the time, our charity now owns two one having lived in five different unite in her joy by following her thirds of Priory Court next door to European countries and stayed in openness to God’s call. Our our Shrine, but we have only eight many more over the past twenty- communal entrustment unites us months left to raise the missing five years, I affirm that I love together as the people of our £140,000.00 needed to buy the last Europe deeply, as a continent and in country in prayer, by renewing the third. Thankfully we use the leased its distinct countries. Europe is vows of dedication made to the premises already, as depicted on the rooted in Christ, but those making Virgin Mary by our ancestors. -

Turning Points General Church

TURNING POINTS OF GENERAL CHURCH HISTORY. BY THE REV. EDWARD L. CUTTS, B.A., HoN. D.D. UNIVERSITY OF THE SoUTH, U.S.A., Author of " Turning Point; of Eng/i;I, Church History"; " Constantine"; "C,:a• /emav1e "; "St. Jerome and St. Augusti11e,,, in the Fathers for English Readers; '' S,me Chief 'Truths of Refig;on "; "Pastora/ Counsels"; fsc, SEVENTH THOUSAND. l'UBL!SHED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE TRACT COMMITTEI!, LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, 1-0RTHUMBERLASTJ AVENUE, CHARl~G CROSS, W,C.; 4J, Q.YEEN VICTORIA STREET, E.C.; 2.6, ST, GEORGE1S "PT.ACE,- HYDE PARK. CORNER, S.W, BRIGHTON : q;, NORTH STREET. ~EW You:: E. & J. B. YOUNG & co. PREFACE. -+-- Tms is an attempt to .give, within the limits of a small book, some adequate idea of the history of the Church oJ Christ to the thousands of intelligent Church-people who have little previous acquaintance with the subject. The special features of the plan are these :-Pains have been taken to show what the Church is-viz., the Body of Christ informed by the Holy Spirit; the salient points of the history have been selected with a special view to our present ecclesiastical condition; instead of referring the reader to other books_, to which he may not have ready access, foc that sketch of secular history wAich is indispensable to an intelligent grasp of Church history, suc,1 a s ... etch is included. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. THI. WORLD l'RXPARED FOR THE CHURCH. PAGI The three great races-Greek, Jewish, Roman; Greek philosophy Epicureanism, Stoicism, Platonism, Eclecticism ; Greek philosophy widely spread by the conquests of Alexander ; The diffusion of the Jews-they bear witness to the unity of God and the promise ui ,a 'saviour; The Roman empire throws down the barriers which divided the nations, and prepares the world for the planting of the Church ..................................................................