Transcript of the Podcast Audio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCTOBER 2019 No 10

OCTOBER 2019 NO 10 ligious and lai News Re ty th AAof the Assumption e same mission EDITORIAL Happy are those called to the supper of the Lord « For us religious, it is necessary to center our lives on the Word of God. It is crucial that this Word becomes the source of life and renewal. » >> Official Agenda Jubilee of the Province of Africa The Assumptionist Province of Africa celebrates its 50th Plenary General Council anniversary this year: a jubilee celebrated in Butembo • n° 5 : December 2-10, 2019, in Rome. at the end of the month of August. The following is the • n° 6 : June 2-10, 2020, in Worcester (United letter addressed by the Superior General for this occa- States). sion, on August 19, 2019, to Fr. Yves Nzuva Kaghoma, • n° 7 : December 3-11, 2020, in Nîmes Provincial Superior: (France). Dear Brothers of the African Province, Ordinary General Councils • n° 16: November 11-15, 2019. It was 50 years ago, on July 3, 1969, that the Province of • n° 17 : December 11-12, 2019. Africa was founded. Resulting from long missionary work by • n° 18 : February 10-14, 2020. the Assumptionists, the young Province began its process • n° 19 : March 18-19, 2020. of development and the progressive assumption of respon- • n° 20 : April 20-24, 2020. sibility by the indigenous brothers. Today, though the mis- Benoît sionary presence is very limited---too limited in my eyes---, you have yourselves become missionaries. The important • October 1-10: Belgium and the Netherlands. number of religious present to the stranger for pastoral rea- • October 20-November 6: Madagascar. -

Medieval Devotion to Mary Among the Carmelites Eamon R

Marian Studies Volume 52 The Marian Dimension of Christian Article 11 Spirituality, Historical Perspectives, I. The Early Period 2001 The aM rian Spirituality of the Medieval Religious Orders: Medieval Devotion to Mary Among the Carmelites Eamon R. Carroll Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Carroll, Eamon R. (2001) "The aM rian Spirituality of the Medieval Religious Orders: Medieval Devotion to Mary Among the Carmelites," Marian Studies: Vol. 52, Article 11. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol52/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Carroll: Medieval Devotions…Carmelites The Marian Spirituality of the Medieval Religious Orders: Medieval Devotion ... Carmelites MEDIEVAL DEVOTION TO MARY AMONG THE CARMELITES Eamon R. Carroll, 0. Carm. * The word Carmel virtually defines the religious family that calls itself the Carmelite Order. It is a geographical designation (as in also Carthusian and Cistercian), not a person's name like Francis, Dominic and the Servite Seven Holy Founders. In the Church's calendar, Carmel is one of three Marian sites celebrated liturgically, along with Lourdes and St. Mary Major. It may be asked: Who founded the Carmelites on Mount Carmel? There is no easy answer, though some names have been suggested, begin, ning with the letter B-Brocard, Berthold, ...What is known is that during the Crusades in the late eleven,hundreds some Euro, peans settled as hermits on Mount Carmel, in the land where the Savior had lived. -

Emmanuel D'alzon

Gaétan Bernoville EMMANUEL D’ALZON 1810-1880 A Champion of the XIXth Century Catholic Renaissance in France Translated by Claire Quintal, docteur de l’Université de Paris, and Alexis Babineau, A.A. Bayard, Inc. For additional information about the Assumptionists contact Fr. Peter Precourt at (508) 767-7520 or visit the website: www.assumptionists.org © Copyright 2003 Bayard, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission of the publisher. Write to the Permissions Editor. ISBN: 1-58595-296-6 Printed in Canada Contents Contents Preface ................................................................................................. 5 Foreword .............................................................................................. 7 Historical Introduction ......................................................................... 13 I. The Child and the Student (1810-1830) .................................. 27 II. From Lavagnac to the Seminary of Montpellier and on to Rome (1830-1833).................................................................... 43 III. The Years in Rome (1833-1835) ............................................... 61 IV. The Vicar-General (1835-1844) ................................................ 81 V. Foundation of the Congregation of the Assumption (1844-1851) .............................................................................. 99 VI. The Great Trial in the Heat of Action (1851-1857) .................. 121 VII. From the Defense -

The Autobiography of St. Anthony Mary Claret

Saint Anthony Mary Claret AUTOBIOGRAPHY Edited by JOSÉ MARIA VIÑAS, CMF Director Studium Claretianum Rome Forward by ALFRED ESPOSITO, CMF Claretian Publications Chicago, 1976 FOREWORD The General Prefecture for Religious Life has for some time wanted to bring out a pocket edition of the Autobiography of St. Anthony Mary Claret to enable all Claretians to enjoy the benefit of personal contact with the most authentic source of our charism and spirit. Without discounting the value of consulting other editions, it was felt there was a real need to make this basic text fully available to all Claretians. The need seemed all the more pressing in view of the assessment of the General Chapter of 1973: "Although, on the one hand, the essential elements and rationale of our charism are sufficiently explicit and well defined in the declarations 'On the Charism of our Founder' and 'On the Spiritual Heritage of the Congregation' (1967), on the other hand, they do not seem to have been sufficiently assimilated personally or communitarily, or fully integrated into our life" (cf. RL, 7, a and b). Our Claretian family's inner need to become vitally aware of its own charism is a matter that concerns the whole Church. Pope Paul's motu proprio "Ecclesiae Sanctae" prescribes that "for the betterment of the Church itself, religious institutes should strive to achieve an authentic understanding of their original spirit, so that adhering to it faithfully in their decisions for adaptation, religious life may be purified of elements that are foreign to it and freed from whatever is outdated" (II, 16, 3). -

VOWS in the SECULAR ORDER of DISCALCED CARMELITES Fr

VOWS IN THE SECULAR ORDER OF DISCALCED CARMELITES Fr. Michael Buckley, OCD The moment we hear the word “Vows” we think automatically of religious. The “vows of religion” is a phrase that comes immediately to our minds: vows and religion are always associated in our thinking. Indeed, for religious men and women, vows of poverty, chastity and obedience are of the very essence of their vocation. Regularly vows are made after novitiate, and again a few years later; the only difference is between simple (temporary) and solemn (perpetual) vows. So it is a new concept when we encounter vows in the context of a Secular Order as we do in Carmel. Yet, the exclusive association of vows with religious people is not warranted. A glance at the Canon Law of the Church will illustrate this. The Canon Law speaks about vows in numbers 1191-98, just before a chapter on oaths. Our Secular legislation makes no reference to the Canon Law when it speaks about vows. That is not necessarily a defect or lacuna in our Constitutions. Our legislation is in accord with sacred canons, but it is essential to be familiar with these. Let me summarize the chapter. It begins with a precise definition: “A vow is a deliberate and free promise made to God concerning a possible and better good which must be fulfilled by reason of the virtue of religion.” Then it goes on to distinguish vows which are a) public, i.e., accepted in the name of the church, b) solemn or simple, c) personal or real, d) how vows cease or are dispensed, etc. -

CARMELITES REMEMBER the MISSION Mount Carmel N Honor of Veterans Day, Commit to the Mission

Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Pray for us. Volume 18, Issue 1 May 2011 Published by the Mount Carmel Alumni Foundation CARMELITES REMEMBER THE MISSION Mount Carmel n honor of Veterans Day, commit to The Mission. Alma Mater Carmelite Alumni veterans On peaceful shores from Mt. Carmel High In 1934 the Carmelites began their ‘neath western skies our I hymn of praise we sing, School and Crespi Carmelite Los Angeles mission building High School gathered to watch Mount Carmel High School on To thee our Alma Mater dear, now let our voices the Crespi vs. Loyola football 70th and Hoover. Their mission ring! game and to reminisce and re- was to provide a Catholic college All hail to thee Mount Carmel High, Crusaders Sons are we! We love your ways, your spirit bold! We pledge ourselves to thee! Inside this issue: Carmelites recall the mission . 1,2 The Lady of the Place . 3 Golf Tournament Monday, May 16th 2011. 4,5 Field of Dreams . 6 Who designed the Crusader Picture L-R…Aviators share mission stories… Website. 7 A Haire Affair & Ryan Michael O’Brien MC’41 flew 35 bombing missions over other annoucements . 8 Germany in WWII receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross. Dec. Board Meeting . 9 Lt. Col Kim “Mo” Mahoney USMC CHS’88, pilots F-18’s and is a veteran of three Iraq deployments. Lt. Col. Joe Faherty MC’63 USAF (RET) flew C-130’s in Viet Nam. Continued on Page 2 The purpose of the Mount Carmel Alumni Foundation is to provide financial assistance to the Carmelite Community and to the Catholic elementary schools in South-Central Los Angeles that have provided our alumni with an excellent education. -

The Charterhouse of Nonenque: a Discussion of an Existing Medieval Nunnery in the Context of Carthusian Architecture

The charterhouse of Nonenque: a discussion of an existing medieval nunnery in the context of Carthusian architecture Carol Steyn Research fellow, Department of Art History, Visual Arts and Musicology, University of South Africa E-mail: [email protected] The Charterhouse of Nonenque is one of the few remaining charterhouses for nuns in the world. It was built in the 12th century as a Cistercian Abbey and adapted in the early 20th century as a Carthusian charterhouse. In this article the buildings of Nonenque are described according to the plans of the layout after a brief history of the abbey. The structure of the buildings is discussed in the context of Carthusian architecture and also in the context of the Carthusian way of life. Carthusian architecture is shown to be unique in monastic architecture since the Carthusian way of life demands greater solitude than those of the other orders and buildings are constructed to make provision for this. Since Nonenque was adapted from a Cistercian building the measures needed to adapt buildings of other orders to Carthusian needs are discussed. These adaptations are more radical in the case of Charterhouses for monks than in those for nuns. Works of art at Nonenque are discussed briefly. This article on Nonenque follows on a visit of a few days which I was allowed to make to the nunnery in 2004. Die Kartuisiese klooster van Nonenque: 'n bespreking van 'n bestaande middeleeuse nonneklooster in die verband van Kartuisiese argitektuur Die Kartuisiese klooster van Nonenque is een van die min oorblywende Kartuisiese kloosters vir nonne in die wêreld. -

Who Are the Secular Franciscans, and What Do They Do?

Who are the Secular Franciscans, and what do they do? The Secular Franciscan Order is a vocation, a Way of Life approved by the Church, for men and women, married or single, who are called to take an active part in the mission of Christ to bring "the good news of salvation" to the world. Secular Franciscans commit themselves to a life in Christ calling for a positive effort to promote Gospel attitudes among their contemporaries. They are united with each other in communities, through which they develop a sense of direction according to the Gospel spirit of Saint Francis of Assisi. FRANCIS, the saint known and loved the world over, was born at Assisi, central Italy, in the year 1181, the son of a wealthy merchant. He died there in 1226, after a life in Christ that earned him the title Poverelo (little poor man). As a youth, Francis had a series of powerful incidents of conversion, including a vision in which Jesus told him to "rebuild my church, for it is falling into ruin." He found Jesus in the poor and suffering, especially the lepers. He and his followers became visible exemplars of a literal Christian life. In the words of Pope Pius XI, "So lifelike and strikingly did the image of Jesus Christ and the Gospel manner of life shine forth in Francis, that he appeared to his contemporaries almost as though he were the Risen Christ." Saint Francis attained this marvelous ideal by making the holy Gospel, in every detail, the rule and standard of his life. -

Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church

Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church We are a pilot parish with Dynamic Catholic (2018-2023) March 7, 2021 3rd Sunday of Lent DAILY MASSES: Monday—Friday: 7am & 9am, Saturday 9am Public Holidays: 9am only WEEKEND MASSES: Saturday: Vigil 5pm Sunday: 8am, 10am, 12 noon Holy Days: As Announced in Bulletin/Website Sacrament Info: See inside Church open weekdays until 4pm All are welcome! Rectory Office: 34-24 203 Street, Bayside, NY 11361-1152 PH: (718) 229-5929, Fax (718) 229-3354 Office Hours: Monday to Friday: 9am to 5pm Website: www.olbs-queens.org Deanery: www.queensdeanery5.org Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament Church Bayside PARISH E-NEWS LETTER! We are served by: Rev. Robert J. Whelan, Pastor Deacon Ernesto Avallone Ext. 124 [email protected] [email protected] Rev. Ernest Makata, p/t Associate; p/t Chaplain NYQPH Deacon William J. Molloy Ext. 118 [email protected] [email protected] Rev. Bryan J. Carney, Resident Mrs. Kathleen Giuliano, Youth Ministry Ext. 120 (Chaplain - Flushing Hospital) [email protected] Sister Nora Gatto, DC, Pastoral Associate Mr. Michael Martinka, Director of Music Ext. 121 [email protected] Ext. 117 [email protected] Mrs. Joan Kane, OLBS Catholic Academy Principal Mrs. Marsha Quilang, Secretary/Bookkeeper 34-45 202 Street, Bayside, NY 11361-1152 Ext. 110 [email protected] (718) 229-4434 Office www.olbsacademy.org [email protected] Mrs. Jeannine Iocco, Coordinator of Religious Education Receptionist, Daily Volunteers (718) 225-6179 [email protected] During Office Hours, Ext. 111 Mrs. -

The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses During the Middle Ages

Geography and circulation of artistic models The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses during the Middle Ages Cristina DAGALITA ABSTRACT In 1084, Bruno of Cologne established the Grande Chartreuse in the Alps, a monastery promoting hermitic solitude. Other charterhouses were founded beginning in the twelfth century. Over time, this community distinguished itself through the ideal purity of its contemplative life. Kings, princes, bishops, and popes built charterhouses in a number of European countries. As a result, and in contradiction with their initial calling, Carthusians drew closer to cities and began to welcome within their monasteries many works of art, which present similarities that constitute the identity of Carthusians across borders. Jean de Marville and Claus Sluter, Portal of the Chartreuse de Champmol monastery church, 1386-1401 The founding of the Grande Chartreuse in 1084 near Grenoble took place within a context of monastic reform, marked by a return to more strict observance. Bruno, a former teacher at the cathedral school of Reims, instilled a new way of life there, which was original in that it tempered hermitic existence with moments of collective celebration. Monks lived there in silence, withdrawn in cells arranged around a large cloister. A second, smaller cloister connected conventual buildings, the church, refectory, and chapter room. In the early twelfth century, many communities of monks asked to follow the customs of the Carthusians, and a monastic order was established in 1155. The Carthusians, whose calling is to devote themselves to contemplative exercises based on reading, meditation, and prayer, in an effort to draw as close to the divine world as possible, quickly aroused the interest of monarchs. -

Into Great Silence Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Into Great Silence Discussion Guide Director: Philip Gröning Year: 2005 Time: 169 min You might know this director from: The Policeman’s Wife (2013) Into Great Silence Love, Money, Love (2000) Philosophie (1998) Die Terroristen! (1992) Sommer (1988) FILM SUMMARY In 1984, director Philip Gröning wrote to the Carthusian monks with a proposal to film a documentary on their unique life of secluded spirituality at the magnificently austere Grande Chartreuse monastery, located deep in the remoteness of the French Alps. Sixteen years later, he received an unlikely reply in which he was invited to film if he was still interested. Ordinarily visitors are not permitted at the monastery, so Gröning accepted under the stringent terms that he would live and work as the monks do, in silence, filming only in his free time. Over a six month period, the director filmed the daily routine of the monks as they live by the Carthusian statutes, which calls for the solitary contemplation of the holy in order to unite one’s life to charity and purity of heart. Devout in this endeavor, each of these men spend their days studying scripture and praying in the seclusion of their own living quarters, only venturing out to complete their portion of the daily chores or to convene for communal worship. Though they appear grateful for their asceticly spiritual lifestyle, to the outside onlooker it may appear more an exercise in mental endurance than a modus of divine deliverance. Bathed in natural light and the reverberating hymns that provide a haunting aural counterbalance to the overbearing silence that pervades the film, Gröning’s documentation of the Carthusians is an entrancing meditation on time, devotion, faith and contemplation itself. -

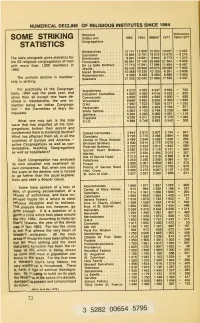

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ...