11 Notations in Carthusian Liturgical Books: Preliminary Remarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses During the Middle Ages

Geography and circulation of artistic models The Commissioning of Artwork for Charterhouses during the Middle Ages Cristina DAGALITA ABSTRACT In 1084, Bruno of Cologne established the Grande Chartreuse in the Alps, a monastery promoting hermitic solitude. Other charterhouses were founded beginning in the twelfth century. Over time, this community distinguished itself through the ideal purity of its contemplative life. Kings, princes, bishops, and popes built charterhouses in a number of European countries. As a result, and in contradiction with their initial calling, Carthusians drew closer to cities and began to welcome within their monasteries many works of art, which present similarities that constitute the identity of Carthusians across borders. Jean de Marville and Claus Sluter, Portal of the Chartreuse de Champmol monastery church, 1386-1401 The founding of the Grande Chartreuse in 1084 near Grenoble took place within a context of monastic reform, marked by a return to more strict observance. Bruno, a former teacher at the cathedral school of Reims, instilled a new way of life there, which was original in that it tempered hermitic existence with moments of collective celebration. Monks lived there in silence, withdrawn in cells arranged around a large cloister. A second, smaller cloister connected conventual buildings, the church, refectory, and chapter room. In the early twelfth century, many communities of monks asked to follow the customs of the Carthusians, and a monastic order was established in 1155. The Carthusians, whose calling is to devote themselves to contemplative exercises based on reading, meditation, and prayer, in an effort to draw as close to the divine world as possible, quickly aroused the interest of monarchs. -

Into Great Silence Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Into Great Silence Discussion Guide Director: Philip Gröning Year: 2005 Time: 169 min You might know this director from: The Policeman’s Wife (2013) Into Great Silence Love, Money, Love (2000) Philosophie (1998) Die Terroristen! (1992) Sommer (1988) FILM SUMMARY In 1984, director Philip Gröning wrote to the Carthusian monks with a proposal to film a documentary on their unique life of secluded spirituality at the magnificently austere Grande Chartreuse monastery, located deep in the remoteness of the French Alps. Sixteen years later, he received an unlikely reply in which he was invited to film if he was still interested. Ordinarily visitors are not permitted at the monastery, so Gröning accepted under the stringent terms that he would live and work as the monks do, in silence, filming only in his free time. Over a six month period, the director filmed the daily routine of the monks as they live by the Carthusian statutes, which calls for the solitary contemplation of the holy in order to unite one’s life to charity and purity of heart. Devout in this endeavor, each of these men spend their days studying scripture and praying in the seclusion of their own living quarters, only venturing out to complete their portion of the daily chores or to convene for communal worship. Though they appear grateful for their asceticly spiritual lifestyle, to the outside onlooker it may appear more an exercise in mental endurance than a modus of divine deliverance. Bathed in natural light and the reverberating hymns that provide a haunting aural counterbalance to the overbearing silence that pervades the film, Gröning’s documentation of the Carthusians is an entrancing meditation on time, devotion, faith and contemplation itself. -

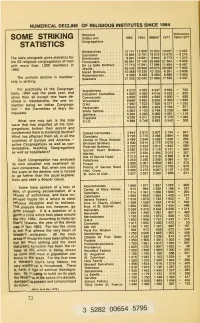

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

The Premonstratensian Project

Chapter 7 The Premonstratensian Project Carol Neel 1 Introduction The order of Prémontré, in the hundred years after the foundation of its first religious community in 1120, instantiated the vibrant religious enthusiasm of the long twelfth century. Like other religious orders originating in the medieval reformation of Catholic Christianity, the Premonstratensians looked to the early church for their inspiration, but to the rule of Augustine rather than to the rule of Benedict whose reinterpretation defined the still more numerous and influential Cistercians.1 The Premonstratensian framers, in the first in- stance their founder Norbert of Xanten (d. 1134), understood the Augustinian rule to have been composed by the ancient bishop for his own community of priests in Hippo, hence believed it the most ancient and venerable of constitu- tions for intentional religious life in the Latin-speaking West.2 As Regular Can- ons ordained to priesthood and living together in community under the rule of Augustine rather than monks according to a reformed Benedictine model, the Premonstratensians were then both primitivist and innovative. While the or- der of Prémontré embraced the novelty of its own project in interpreting the Augustinian ideal for a Europe reshaped by Gregorian Reform, burgeoning lay piety, and a Crusader spirit, at the same time it homed to an ancient paradigm of a priesthood informed and inspired by the sharing of poverty and prayer. Among numerous contemporaneous reform movements and religious com- munities claiming return to apostolic values, the medieval Premonstratensians thus maintained a vivid consciousness of the distinctiveness of their charism as a mixed apostolate bringing together contemplative retreat and active en- gagement in the secular world. -

Being Seen: an Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia J

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College History Honors Projects History Department Spring 4-21-2011 Being Seen: An Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia J. Belote Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/history_honors Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Other Applied Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Belote, Olivia J., "Being Seen: An Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome" (2011). History Honors Projects. Paper 9. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/history_honors/9 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Being Seen: An Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia Joy Belote Honors Project, History 2011 1 History Honors 2011 Advisor: Peter Weisensel Second Readers: Kristin Lanzoni and Susanna Drake Contents Page Introduction..................................................................................................................3 Feminist History and Females in Christianity..............................................................6 The -

SPIRITUALITY: ABCD's “Catholic Spirituality” This Work Is a Study in Catholic Spirituality. Spirituality Is Concerned With

SPIRITUALITY: ABCD’s “Catholic Spirituality” This work is a study in Catholic spirituality. Spirituality is concerned with the human subject in relation to God. Spirituality stresses the relational and the personal though does not neglect the social and political dimensions of a person's relationship to the divine. The distinction between what is to be believed in the do- main of dogmatic theology (the credenda) and what is to be done as a result of such belief in the domain of moral theology (the agenda) is not always clear. Spirituality develops out of moral theology's concern for the agenda of the Christian life of faith. Spirituality covers the domain of religious experience of the divine. It is primarily experiential and practical/existential rather than abstract/academic and conceptual. Six vias or ways are included in this compilation and we shall take a look at each of them in turn, attempting to highlight the main themes and tenets of these six spiritual paths. Augustinian Spirituality: It is probably a necessary tautology to state that Augus- tinian spirituality derives from the life, works and faith of the African Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430). This spirituality is one of conversion to Christ through caritas. One's ultimate home is in God and our hearts are restless until they rest in the joy and intimacy of Father, Son and Spirit. We are made for the eternal Jerusalem. The key word here in our earthly pilgrimage is "conversion" and Augustine describes his own experience of conversion (metanoia) biographically in Books I-IX of his Confessions, a spiritual classic, psychologically in Book X (on Memory), and theologically in Books XI-XIII. -

Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century

A “Truly Unmonastic Way of Life”: Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hannah Elizabeth Ewing Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Timothy Gregory, Advisor Professor Anthony Kaldellis Professor Alison I. Beach Copyright by Hannah Elizabeth Ewing 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines twelfth-century Byzantine writings on monasticism and holy men to illuminate monastic critiques during this period. Drawing upon close readings of texts from a range of twelfth-century voices, it processes both highly biased literary evidence and the limited documentary evidence from the period. In contextualizing the complaints about monks and reforms suggested for monasticism, as found in the writings of the intellectual and administrative elites of the empire, both secular and ecclesiastical, this study shows how monasticism did not fit so well in the world of twelfth-century Byzantium as it did with that of the preceding centuries. This was largely on account of developments in the role and operation of the church and the rise of alternative cultural models that were more critical of traditional ascetic sanctity. This project demonstrates the extent to which twelfth-century Byzantine society and culture had changed since the monastic heyday of the tenth century and contributes toward a deeper understanding of Byzantine monasticism in an under-researched period of the institution. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family, and most especially to my parents. iii Acknowledgments This dissertation is indebted to the assistance, advice, and support given by Anthony Kaldellis, Tim Gregory, and Alison Beach. -

SAINT BRUNO AS SEEN by HIS CONTEMPORARIES a Selection of Contributions to the Funeral Parchment

SAINT BRUNO AS SEEN BY HIS CONTEMPORARIES A Selection of Contributions to the Funeral Parchment TRANSLATED BY A CARTHUSIAN MONK N INTRODUCTION Bruno the hermit Bruno was born around the year 1030 in the city of Cologne, Germany. After studies at the cathedral school there, he was promoted to be a canon of the Church of Saint Cunibert. To complete his studies he moved to Rheims, in France, to the famous cathedral school there. In 1059, not yet thirty years old, he was promoted to the post of direc- tor of studies and chancellor. At about the same time he is appointed a canon of the Cathedral of Rheims. During a period of twenty years Bruno is responsible for the in- tellectual formation of the elite of his time. He gets acquainted with many people who will occupy important positions in Church and so- ciety later on. His disciples hold him in high esteem and will remain grateful for the deep formation they received under his guidance, not only intellectual but also spiritual. However, his time, like ours, is a time of contradictions and radi- cal changes. To stand up against corruption in the Church, the Popes call for a reform ‘in head and members’. Bruno does not keep aloof from this reform, but with several fellow canons firmly makes his stand against his own Archbishop, Manassès, when it becomes clear that the latter is only after power and pursuit of gain. To get his re- 1 venge, the Archbishop expels Bruno from the Diocese. He is only able to return when Manassès is finally deposed by the Pope himself. -

La Chartreuse De Prémol: Physionomie Et Représentation Du Bâti

La chartreuse de Prémol : physionomie et représentation du bâti (XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles) Thomas Pouyet To cite this version: Thomas Pouyet. La chartreuse de Prémol : physionomie et représentation du bâti (XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles). Histoire. 2010. dumas-01145474 HAL Id: dumas-01145474 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01145474 Submitted on 24 Apr 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Thomas POUYET La chartreuse de Prémol. Physionomie et représentation du bâti. XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles. Volume I Mémoire de Master 1 « Sciences humaines et sociales » Mention : Histoire et Histoire de l’art. Spécialité : Sociétés et Economies des mondes Modernes et Contemporains. Sous la direction de M. Alain BELMONT Année universitaire 2009-2010 Thomas POUYET La chartreuse de Prémol. Physionomie et représentation du bâti. XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles. Volume I Mémoire de Master 1 « Sciences humaines et sociales » Mention : Histoire et Histoire de l’art. Spécialité : Sociétés et Economies des mondes Modernes et Contemporains. Sous la direction de M. Alain BELMONT Année universitaire 2009-2010 2 « L’homme doit d’abord se nourrir, se désaltérer, se loger, se vêtir et ensuite seulement, il peut participer à des activités politiques, scientifiques, artistiques ou religieuses. -

Baglin V. Cusenier Co., 221 US

OCTOBER TERM, 1910. Syllabus. 221 U. S. "The people of the United States constitute one nation, under one government, and this government, within the scope of the powers with which it is invested, is supreme. On the other hand, the people of each State compose a State, having its own government, and endowed with all the functions essential to separate and independent ex- istence. The States disunited might continue to exist. Without the States in union there could be no such polit- ical body as the United States." To this we may add that the constitutional equality of the States is essential to the harmonious operation of the scheme upon which the Republic was organized. When that equality disappears we may remain a free people, but the Union will not be the Union of the Constitution. Judgment affirmed. MR. JUSTICE MCKENNA and MR. JUSTICE HOLMES dis- sent. BAGLIN, SUPERIOR GENERAL OF THE ORDER OF CARTHUSIAN MONKS, v. CUSENIER COM- PANY. APPEAL FROM AND ON CERTIORARI TO THE CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT. No. 99. Argued March 14, 15, 1911.-Decided May 29, 1911. While names which are merely geographical cannot be exclusively ap- propriated as trade-marks, a geographical name which for a long period has referred exclusively to a product made at the place and not to the place itself may properly be used as a trade-mark; and so held that the word "Chartreuse" as used by the Carthusian Monks in connection with the liqueur manufactured by them at Grande Chartreuse, France, before their removal to Spain, was a validly reg- istered trade-mark in this country. -

A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (With Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia)

religions Article A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia) Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig Jakobsen Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics, University of Copenhagen, 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] Abstract: Monasticism was introduced to Denmark in the 11th century. Throughout the following five centuries, around 140 monastic houses (depending on how to count them) were established within the Kingdom of Denmark, the Duchy of Schleswig, the Principality of Rügen and the Duchy of Estonia. These houses represented twelve different monastic orders. While some houses were only short lived and others abandoned more or less voluntarily after some generations, the bulk of monastic institutions within Denmark and its related provinces was dissolved as part of the Lutheran Reformation from 1525 to 1537. This chapter provides an introduction to medieval monasticism in Denmark, Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia through presentations of each of the involved orders and their history within the Danish realm. In addition, two subchapters focus on the early introduction of monasticism to the region as well as on the dissolution at the time of the Reformation. Along with the historical presentations themselves, the main and most recent scholarly works on the individual orders and matters are listed. Keywords: monasticism; middle ages; Denmark Citation: Jakobsen, Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig. 2021. A Brief For half a millennium, monasticism was a very important feature in Denmark. From History of Medieval Monasticism in around the middle of the 11th century, when the first monastic-like institutions were Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and introduced, to the middle of the 16th century, when the last monasteries were dissolved Estonia).