Being Seen: an Art Historical and Statistical Analysis of Feminized Worship in Early Modern Rome Olivia J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation to A. D. 1825

: TABLES OP CONTEMPORARY CHUONOLOGY. FROM THE CREATION, TO A. D. 1825. \> IN SEVEN PARTS. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." 3lorttatttt PUBLISHED BY SHIRLEY & HYDE. 1629. : : DISTRICT OF MAItfE, TO WIT DISTRICT CLERKS OFFICE. BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the first day of June, A. D. 1829, and in the fifty-third year of the Independence of the United States of America, Messrs. Shiraey tt Hyde, of said District, have deposited in this office, the title of a book, the right whereof they claim as proprietors, in the words following, to wit Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation, to A.D. 1825. In seven parts. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." In conformity to the act of the Congress of the United States, entitled " An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ;" and also to an act, entitled "An Act supplementary to an act, entitled An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ; and for extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints." J. MUSSEV, Clerk of the District of Maine. A true copy as of record, Attest. J MUSSEY. Clerk D. C. of Maine — TO THE PUBLIC. The compiler of these Tables has long considered a work of this sort a desideratum. -

Spolia's Implications in the Early Christian Church

BEYOND REUSE: SPOLIA’S IMPLICATIONS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN CHURCH by Larissa Grzesiak M.A., The University of British Columba, 2009 B.A. Hons., McMaster University, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Art History) THE UNVERSIT Y OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2011 © Larissa Grzesiak, 2011 Abstract When Vasari used the term spoglie to denote marbles taken from pagan monuments for Rome’s Christian churches, he related the Christians to barbarians, but noted their good taste in exotic, foreign marbles.1 Interest in spolia and colourful heterogeneity reflects a new aesthetic interest in variation that emerged in Late Antiquity, but a lack of contemporary sources make it difficult to discuss the motives behind spolia. Some scholars have attributed its use to practicality, stating that it was more expedient and economical, but this study aims to demonstrate that just as Scripture became more powerful through multiple layers of meaning, so too could spolia be understood as having many connotations for the viewer. I will focus on two major areas in which spolia could communicate meaning within the context of the Church: power dynamics, and teachings. I will first explore the clear ecumenical hierarchy and discourses of power that spolia delineated through its careful arrangement within the church, before turning to ideological implications for the Christian viewer. Focusing on the Lateran and St. Peter’s, this study examines the religious messages that can be found within the spoliated columns of early Christian churches. By examining biblical literature and patristic works, I will argue that these vast coloured columns communicated ideas surrounding Christian doctrine. -

Michelangelo's Locations

1 3 4 He also adds the central balcony and the pope’s Michelangelo modifies the facades of Palazzo dei The project was completed by Tiberio Calcagni Cupola and Basilica di San Pietro Cappella Sistina Cappella Paolina crest, surmounted by the keys and tiara, on the Conservatori by adding a portico, and Palazzo and Giacomo Della Porta. The brothers Piazza San Pietro Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano facade. Michelangelo also plans a bridge across Senatorio with a staircase leading straight to the Guido Ascanio and Alessandro Sforza, who the Tiber that connects the Palace with villa Chigi first floor. He then builds Palazzo Nuovo giving commissioned the work, are buried in the two The long lasting works to build Saint Peter’s Basilica The chapel, dedicated to the Assumption, was Few steps from the Sistine Chapel, in the heart of (Farnesina). The work was never completed due a slightly trapezoidal shape to the square and big side niches of the chapel. Its elliptical-shaped as we know it today, started at the beginning of built on the upper floor of a fortified area of the Apostolic Palaces, is the Chapel of Saints Peter to the high costs, only a first part remains, known plans the marble basement in the middle of it, space with its sail vaults and its domes supported the XVI century, at the behest of Julius II, whose Vatican Apostolic Palace, under pope Sixtus and Paul also known as Pauline Chapel, which is as Arco dei Farnesi, along the beautiful Via Giulia. -

THE SAINT HUGO HERALD Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time| July 4, 2021

! Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time 1 THE SAINT HUGO HERALD Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time| July 4, 2021 THE YEAR OF ST. JOSEPH! page 3! WELCOME FR. MARK BRAUER! ! ! WEEKLY CALENDAR ! On July 1, 2021, Fr. Mark Brauer became the new page 4! ! pastor of St. Hugo of the Hills Catholic Parish and CARILLON SERIES! School. He was ordained to the priesthood on June page 5! 27, 1992, at Blessed Sacrament Cathedral by Cardinal ! AOD COVID UPDATE! Maida. He was born in Detroit Michigan and is one page 6! of eight children born to Corinne and Joseph Brauer. ! He is their sixth child, five boys and three girls.! FR. TONY PARISH SOCIAL! page 7! ! ! This assignment is Fr. Brauer’s fourth since ordinaon RETIREMENT | ! more than twentyRnine years ago. Fr. Mark was the MRS. YUGOVICH! page 8! pastor of Our Lady of Sorrow for the past sixteen ! years. Prior to this assignment, he was Pastor of one FR. ESPER AWARDS! of the first clusters in the archdiocese, St. Chrisne page 9! INDEPENDENCE DAY! ! Parish and St. Gemma Parish, both located on the SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 ! CSA | STEWARDSHIP! west side of Detroit. He served the two parishes for Office Closed ! page 10! ten years. Fr. Mark’s first assignment was as an ! 7:30 a.m., 10:00 a.m., ! Associate Pastor of St. Ephrem Parish in Sterling GOSPEL & READINGS! 12:00 p.m. & 5:00 p.m. ! page 13! Heights. We look forward to having Fr. Mark be part Mass T Church! ! of St. Hugo community. ! WEEKEND MINISTERS! ! page 14! ! MONDAY, JULY 5, 2021 ! MASS INTENTIONS! Office Closed ! page 15! 6:10 a.m. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

Pontifex Maximus

bs_bs_banner Journal of Religious History Vol. ••, No. ••, •• 2016 doi: 10.1111/1467-9809.12400 ROALD DIJKSTRA AND DORINE VAN ESPELO Anchoring Pontifical Authority: A Reconsideration of the Papal Employment of the Title Pontifex Maximus It is a common assumption that the title of supreme priesthood or pontifex maximus is included in the official papal titulature, and it has been supposed that the Roman bishop adopted it from the Roman emperor in late antiquity. In fact, however, it was probably not until the fifteenth century that the designation was first used by the papacy, and it has continued to be part of papal representation ever since. The title was deeply rooted in the Roman imperial past. At several stages in papal history the papal agency felt the need to draw back (again) on this ancient, traditional title and managed to successfully (re-)introduce the title by anchoring it in the cultural biogra- phy of the papacy. Introduction Since Antiquity, the interplay between the Roman bishops and secular rulers has been subject to continuous transformation and renegotiation, as both groups continually reverted to established traditions in order to sustain legiti- macy and pre-eminence.1 At the same time, however, modes of representation had to be innovative in order to appeal to contemporary tastes, needs, and ex- pectations. Anchoring these novelties in tradition was a convenient means of implementing, and reinforcing, the desired effect, and tracing these processes of embedding the new in the familiar offers us the possibility of understanding cultural, political, and religious transformation. An outstanding example of this kind of “anchoring innovation” is that of Roman episcopal titulature, as can be 1. -

The Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe

The Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe November 22, 2020 Regina Coeli Catholic Church 530 Regina Pkwy., Toledo, Ohio 43612 Bullen Deadline: Parish Contact Informaon: Monday by 4:00pm 419R476R0922 reginacoelitoledo.org Please call in advance for an appointment! Sacraments: Bapsm: Please con- tact the parish office to WELCOME! PastorVFr. Miller: (m) 419R217R0228 or [email protected] schedule an appoint- We are glad DeaconV Dcn. Jim Dudley: [email protected] ment. you have joined us! Office ManagerVEdna MiklosekRBaker: rc3offi[email protected] Confessions: 1/2 hour Finance ManagerVOctavia Wayton: rc3fi[email protected] before every Mass and CustodianVMelissa Swackhamer: [email protected] 1 hour before Saturday evening Mass. CCD DirectorVRose Marie Liberkowski: [email protected] Marriage: Couples should contact the parish Music DirectorVAmy Sujkowski: [email protected] office as they begin to make plans for marriage, Finance CouncilVJenny Malaczewski: [email protected] and certainly before they set a wedding date. Cer- Pastoral CouncilV Dcn. Jim Dudley: [email protected] tain days and/or mes may not be available due PrincipalVHeather Radwanski: [email protected] to other previously scheduled weddings or acvi- es in the church. A minimum of six months is Visit our website! hps://www.reginacoelitoledo.org/ required before a wedding can be scheduled in order to allow me for marriage instrucon clas- Mass liveRstreamed Sundays at 10:30am at ses. www.facebook.com/reginacoeliparish/ Anoinng of the Sick: If you wish to receive the Download the Myparish App in the app store Sacrament of the Sick, please call the Parish and search for 43612! Office or, if more urgent, Fr. -

St. Frances of Rome's Visions of Hell

St. Frances of Rome’s Visions of Hell TAKEN FROM THE FRENCH BOOK: THE DEVIL IN THE LIVES OF THE SAINTS Translated December 2019 APPROBATION Being a part of the Choice of Ascetic Readings published by Mr. Thibaud-Landriot and Co., we had one of our grand vicars examine the book entitled “Vie de Sainte Françoise Romaine” (The Life of St. Frances of Rome). According to the report that has been made to us, we willingly give our approval of the book, and we strongly recommend reading it. In Clermont, on January 22nd, 1841. L.C., Bishop of Clermont By Monsignor: Boucard, Chan., Secretary-General All formalities prescribed by law have been fulfilled by the undersigned Publisher-Owners. Thibaud-Landriot and Co. 2 Index Part One 15th century Chapter I Diabolic Persecution Against Saint Frances of Rome Brought corpse. – On burning coals. - In the ashes. – Satanic perfidy. – Infernal group. - Blessed candles. - Hungarian delivered. Chapter II Visions of Saint Frances of Rome. - Entrance to hell. - The divisions of the fallen angels. Chapter III The tactics of temptation. - Immediately after death. - The name of Jesus. Chapter IV Limbo. Chapter V Lucifer's judgment. - The general torments of hell. - The blasphemies of the damned. Chapter VI The torments for each sin and for each kind of damnation Laziness. Gluttony. Dancers. Vanity. Married Women. Vicious Widows. Impure Thoughts. 3 The Incest. Sodomites. Procuring Parents. Religious Who are Unfaithful to the Vow of Chastity. Ungrateful Children. Envy. Haters. Anger. Homicides. Avarice. Usurers. Gamblers. The Prideful. Blasphemers. Traitors. Falsifying Wine Merchants. Fraudulent Butchers. Doctors without a conscience. -

The Turn to Hagiography in Heywood's Reformation

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 19:52 Renaissance and Reformation Renaissance et Réforme “A Virgine and a Martyr both”: The Turn to Hagiography in Heywood’s Reformation History Play Gina M. Di Salvo Volume 41, numéro 4, fall 2018 Résumé de l'article Cet article se penche sur la narration et sur les stratégies théâtrales qu’utilise URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1061917ar Thomas Heywood afin de sanctifier Elisabeth Ière en tant que vierge martyre et DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1061917ar sainte, dans sa pièce If You Know Not Me, You Know Nobody, Part I, or the Troubles of Queen Elizabeth (c. 1605). Cette pièce porte sur l’histoire de la Aller au sommaire du numéro Réforme et, bien que peu étudiée, constitue une oeuvre remarquable. L’article examine comment Heywood va à l’encontre de Foxe, même lorsqu’il emprunte à l’histoire de la Réforme anglaise prise du Book of Martyrs afin de produire le Éditeur(s) récit du martyre d’une vierge. On y discute de quelle façon la théâtralité miraculeuse de la pièce dramatise des connaissances d’histoire religieuse Iter Press passée, et on montre que la pièce regénère une hagiographie pour le protestantisme anglais. On propose en conclusion que le théâtre ISSN hagiographique stuartien est une invention de Heywood. 0034-429X (imprimé) 2293-7374 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Di Salvo, G. M. (2018). “A Virgine and a Martyr both”: The Turn to Hagiography in Heywood’s Reformation History Play. Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme, 41(4), 133–167. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

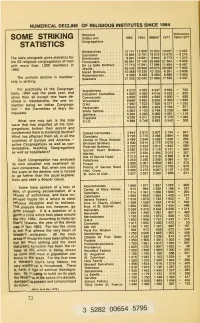

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

1 Target Texts Sourced in Fontes Anglo

Target Texts Sourced in Fontes Anglo-Saxonici Database (arranged alphabetically, by text title) Text Reference Title Author Edition Contributor C.B.19.139 Abdo, Sennes ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 163.7-164.3 C. Rauer C.B.19.038 Adrian, Natalia ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 28.1-29.12 C. Rauer C.B.19.204 Aethelburh ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 228.4-13 C. Rauer C.B.19.110 Aethelthryth ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 127.13-129.12 C. Rauer C.B.19.066 Aethelwald ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 58.1-11 C. Rauer C.B.19.149 Afra, Hilaria etc. ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 173.12-175.4 C. Rauer C.B.19.059 Agape, Chionia (Irene) ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 49.1-50.9 C. Rauer C.B.19.030 Agnes ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 22.14-23.12 C. Rauer C.B.19.171 Aidan ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 195.7-196.2 C. Rauer C.B.19.109 Alban ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 126.10-127.12 C. Rauer C.B.22.1 Alexander's Letter to Aristotle ANON (OE) Orchard 1995 C. Rauer C.B.19.071 Alexandria ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 66.3-67.7 C. Rauer C.B.19.218 All Saints ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 243.7-244.7 C. Rauer C.B.19.060 Ambrose of Milan ANON (OE Martyrology) Kotzor 1981, 2, 50.10-51.13 C.