Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger – the First One Not to Become a Blind Man? Political and Military History of the Bryennios Family in the 11Th and Early 12Th Century

Studia Ceranea 10, 2020, p. 31–45 ISSN: 2084-140X DOI: 10.18778/2084-140X.10.02 e-ISSN: 2449-8378 Marcin Böhm (Opole) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5393-3176 Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger – the First One Not to Become a Blind Man? Political and Military History of the Bryennios Family in the 11th and Early 12th Century ikephoros Bryennios the Younger (1062–1137) has a place in the history N of the Byzantine Empire as a historian and husband of Anna Komnene (1083–1153), a woman from the imperial family. His historical work on the his- tory of the Komnenian dynasty in the 11th century is an extremely valuable source of information about the policies of the empire’s major families, whose main goal was to seize power in Constantinople1. Nikephoros was also a talented commander, which he proved by serving his father-in-law Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118) and brother-in-law John II Komnenos (1118–1143). The marriage gave him free access to people and documents which he also enriched with the history of his own family. It happened because Nikephoros Bryennios was not the first representative of his family who played an important role in the internal policy of the empire. He had two predecessors, his grandfather, and great grand- father, who according to the family tradition had the same name as our hero. They 1 J. Seger, Byzantinische Historiker des zehnten und elften Jahrhunderts, vol. I, Nikephoros Bryennios, München 1888, p. 31–33; W. Treadgold, The Middle Byzantine Historians, Basingstoke 2013, p. 344–345; A. -

Byzantine Conquests in the East in the 10 Century

th Byzantine conquests in the East in the 10 century Campaigns of Nikephoros II Phocas and John Tzimiskes as were seen in the Byzantine sources Master thesis Filip Schneider s1006649 15. 6. 2018 Eternal Rome Supervisor: Prof. dr. Maaike van Berkel Master's programme in History Radboud Univerity Front page: Emperor Nikephoros II Phocas entering Constantinople in 963, an illustration from the Madrid Skylitzes. The illuminated manuscript of the work of John Skylitzes was created in the 12th century Sicily. Today it is located in the National Library of Spain in Madrid. Table of contents Introduction 5 Chapter 1 - Byzantine-Arab relations until 963 7 Byzantine-Arab relations in the pre-Islamic era 7 The advance of Islam 8 The Abbasid Caliphate 9 Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty 10 The development of Byzantine Empire under Macedonian dynasty 11 The land aristocracy 12 The Muslim world in the 9th and 10th century 14 The Hamdamids 15 The Fatimid Caliphate 16 Chapter 2 - Historiography 17 Leo the Deacon 18 Historiography in the Macedonian period 18 Leo the Deacon - biography 19 The History 21 John Skylitzes 24 11th century Byzantium 24 Historiography after Basil II 25 John Skylitzes - biography 26 Synopsis of Histories 27 Chapter 3 - Nikephoros II Phocas 29 Domestikos Nikephoros Phocas and the conquest of Crete 29 Conquest of Aleppo 31 Emperor Nikephoros II Phocas and conquest of Cilicia 33 Conquest of Cyprus 34 Bulgarian question 36 Campaign in Syria 37 Conquest of Antioch 39 Conclusion 40 Chapter 4 - John Tzimiskes 42 Bulgarian problem 42 Campaign in the East 43 A Crusade in the Holy Land? 45 The reasons behind Tzimiskes' eastern campaign 47 Conclusion 49 Conclusion 49 Bibliography 51 Introduction In the 10th century, the Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors coming from the Macedonian dynasty. -

BYZANTINE CAMEOS and the AESTHETICS of the ICON By

BYZANTINE CAMEOS AND THE AESTHETICS OF THE ICON by James A. Magruder, III A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March 2014 © 2014 James A. Magruder, III All rights reserved Abstract Byzantine icons have attracted artists and art historians to what they saw as the flat style of large painted panels. They tend to understand this flatness as a repudiation of the Classical priority to represent Nature and an affirmation of otherworldly spirituality. However, many extant sacred portraits from the Byzantine period were executed in relief in precious materials, such as gemstones, ivory or gold. Byzantine writers describe contemporary icons as lifelike, sometimes even coming to life with divine power. The question is what Byzantine Christians hoped to represent by crafting small icons in precious materials, specifically cameos. The dissertation catalogs and analyzes Byzantine cameos from the end of Iconoclasm (843) until the fall of Constantinople (1453). They have not received comprehensive treatment before, but since they represent saints in iconic poses, they provide a good corpus of icons comparable to icons in other media. Their durability and the difficulty of reworking them also makes them a particularly faithful record of Byzantine priorities regarding the icon as a genre. In addition, the dissertation surveys theological texts that comment on or illustrate stone to understand what role the materiality of Byzantine cameos played in choosing stone relief for icons. Finally, it examines Byzantine epigrams written about or for icons to define the terms that shaped icon production. -

Number 35 July-September

THE BULB NEWSLETTER Number 35 July-September 2001 Amana lives, long live Among! ln the Kew Scientist, Issue 19 (April 2001), Kew's Dr Mike Fay reports on the molecular work that has been carried out on Among. This little tulip«like eastern Asiatic group of Liliaceae that we have long grown and loved as Among (A. edulis, A. latifolla, A. erythroniolde ), but which took a trip into the genus Tulipa, should in fact be treated as a distinct genus. The report notes that "Molecular data have shown this group to be as distinct from Tulipa s.s. [i.e. in the strict sense, excluding Among] as Erythronium, and the three genera should be recognised.” This is good news all round. I need not change the labels on the pots (they still labelled Among), neither will i have to re~|abel all the as Erythronlum species tulips! _ Among edulis is a remarkably persistent little plant. The bulbs of it in the BN garden were acquired in the early 19605 but had been in cultivation well before that, brought back to England by a plant enthusiast participating in the Korean war. Although not as showy as the tulips, they are pleasing little bulbs with starry white flowers striped purplish-brown on the outside. It takes a fair amount of sun to encourage them to open, so in cool temperate gardens where the light intensity is poor in winter and spring, pot cultivation in a glasshouse is the best method of cultivation. With the extra protection and warmth, the flowers will open out almost flat. -

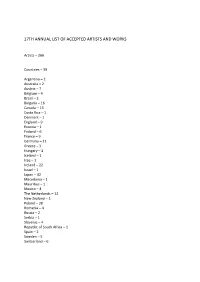

17Th Annual List of Accepted Artists and Works

17TH ANNUAL LIST OF ACCEPTED ARTISTS AND WORKS Artists – 266 Countries – 39 Argentina – 2 Australia – 2 Austria – 7 Belgium – 4 Brazil – 2 Bulgaria – 16 Canada – 13 Costa Rica – 1 Denmark – 1 England – 9 Estonia – 1 Finland – 6 France – 9 Germany – 11 Greece – 3 Hungary – 2 Iceland – 1 Iraq – 1 Ireland – 22 Israel – 1 Japan – 42 Macedonia – 1 Mauritius – 1 Mexico – 4 The Netherlands – 12 New Zealand – 1 Poland – 38 Romania – 4 Russia – 2 Serbia – 1 Slovenia – 4 Republic of South Africa – 1 Spain – 2 Sweden – 5 Switzerland – 6 Taiwan – 2 Thailand – 2 U. S. A. – 22 Venezuela – 1 Featured Artist DIMO KOLIBAROV, Bulgaria Cycle of prints Meetings with Bulgarian Printmaking Artists Presentation of the First Prize Winner of the 16th Mini Print Annual 2017 EVA CHOUNG – FUX, Austria Special Presentation FACULTY OF ARTS MARIA CURIE SKŁODOWSKA UNIVERSITY Lublin, Poland Dr hab. Adam Panek The cycle of prints: 1. Triptych I – A, 2018, Linocut, 15 x 11 cm 2. Triptych I – B, 2018, Linocut, 15 x 9 cm 3. Triptych I – C, 2018, Linocut, 15,5 x 11 cm Dr hab. Alicja Snoch-Pawłowska The cycle of prints: 1. Diffusion 1, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18,5 cm 2. Diffusion 2, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18 cm 3. Diffusion 3, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18,5 cm Dr Amadeusz Popek The cycle of prints: 1. Mirage-Róża, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm 2. Mirage-Pejzaż górski, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm 3. Mirage, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm Mgr Andrzej Mosio The cycle of prints: 1. -

The Costume of Byzantine Emperors and Empresses ’

Shaw, C. (2011) ‘The Costume of Byzantine Emperors and Empresses ’ Rosetta 9.5: 55-59. http://www.rosetta.bham.ac.uk/colloquium2011/shaw_costume.pdf http://www.rosetta.bham.ac.uk/colloquium2011/shaw_costume.pdf The Costume of the Byzantine Emperors and Empresses Carol Shaw PhD candidate, 4th year (part-time) University of Birmingham, College of Arts and Law [email protected] The Costume of the Byzantine Emperors and Empresses The first Roman emperors were all members of the senate and continued to belong to it throughout their reigns.1 All the members of the senate including the emperor wore tunics and togas decorated with a wide purple band, the latus clavus, and special footwear.2 During the period of instability in the early third century several emperors were selected by the army.3 Initially this shift in power did not affect court ceremony and dress; but slowly both began to change. Court ceremony became more formal and emperors distanced themselves even from senators.4 During the late third century, Diocletian introduced the new court ceremony of the adoration of the purple; according to Aurelius Victor, the emperor also wore richly brocaded purple robes, silks and jeweled sandals.5 Diocletian’s abdication ceremony illustrates that court ceremony and dress often remained very simple. The only garment closely associated with imperial power at this time was the emperor’s purple robes. In his On the Deaths of the Persecutors, Lactantius records that in AD 305 when Diocletian abdicated, the ceremony consisted of the emperor standing under a statue of his patron deity, 1 Under the law the Lex Ovinia (enacted by 318 BC), censors selected each senator according to certain criteria. -

Imge A&Ea Dem Bepaa® Dbs P&Mareaats Mattaabs' I, Voa Kanflftaaimopat, By3, 37, 1987 (1S88), 417=418

Durham E-Theses Matthew I, Patriarch of Constantinople (1397 - 1410), his life, his patriarchal acts, his written works Kapsalis, Athanasius G. How to cite: Kapsalis, Athanasius G. (1994) Matthew I, Patriarch of Constantinople (1397 - 1410), his life, his patriarchal acts, his written works, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5836/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 MATTHEW I, PATRIARCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE (1397 - 1410), HIS LIFE, HIS PATRIARCHAL ACTS, HIS WRITTEN WORK: The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. MASTER OF ARTS THESIS, SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM 1994 A 4} nov m This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research or private study on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement.' =1= CONTENTS ABSTRACT XV-V LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS VX-VIII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS DC NOTES ON PROPER NAMES X GENERAL INTRODUCTION A brief Historical, Political and Eccle• siastical description of Byzantium during the XTV century and the beginning of the XV. -

Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Galliker, Julia, "Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204)" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 27. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker, University of Michigan In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. Salvatore Gaspa, Cécile Michel, & Marie-Louise Nosch (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2017), pp. 346-373. -

Canon Law of Eastern Churches

KB- KBZ Religious Legal Systems KBR-KBX Law of Christian Denominations KBR History of Canon Law KBS Canon Law of Eastern Churches Class here works on Eastern canon law in general, and further, on the law governing the Orthodox Eastern Church, the East Syrian Churches, and the pre- Chalcedonean Churches For canon law of Eastern Rite Churches in Communion with the Holy See of Rome, see KBT Bibliography Including international and national bibliography 3 General bibliography 7 Personal bibliography. Writers on canon law. Canonists (Collective or individual) Periodicals, see KB46-67 (Christian legal periodicals) For periodicals (Collective and general), see BX100 For periodicals of a particular church, see that church in BX, e.g. BX120, Armenian Church For periodicals of the local government of a church, see that church in KBS Annuals. Yearbooks, see BX100 Official gazettes, see the particular church in KBS Official acts. Documents For acts and documents of a particular church, see that church in KBS, e.g. KBS465, Russian Orthodox Church Collections. Compilations. Selections For sources before 1054 (Great Schism), see KBR195+ For sources from ca.1054 on, see KBS270-300 For canonical collections of early councils and synods, both ecumenical/general and provincial, see KBR205+ For document collections of episcopal councils/synods and diocesan councils and synods (Collected and individual), see the church in KBS 30.5 Indexes. Registers. Digests 31 General and comprehensive) Including councils and synods 42 Decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts (Collective) Including related materials For decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts of a particular church, see that church in KBS Encyclopedias. -

Byzantine Legal Culture and the Roman Legal Tradition, 867-1056 1St Edition Download Free

BYZANTINE LEGAL CULTURE AND THE ROMAN LEGAL TRADITION, 867-1056 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Zachary Chitwood | 9781107182561 | | | | | Byzantine Empire See also: Byzantine Empire under the Heraclian dynasty. Retrieved February 23, Theophylact Patriarch of Constantinople With the exception of a few cities, and especially Constantinoplewhere other 867-1056 1st edition of urban economic activities were also developed, Byzantine society remained at its heart agricultural. Born in at ArabissusCappadocia. The Persian Empire is the name given to a series of dynasties centered in modern-day Iran that spanned several Byzantine Legal Culture and the Roman Legal Tradition the sixth century B. Amorian dynasty — [ edit ] See also: Byzantine Empire under the Amorian dynasty. After becoming the emperor's father-in-law, he successively assumed higher offices until he crowned himself senior emperor. Named his sons MichaelAndronikos and Konstantios as co-emperors. In: L. Only son of Andronikos III, he had not been crowned co-emperor or declared heir at his father's death, a fact which led to the outbreak of a destructive civil war between his regents and his father's closest aide, John VI Kantakouzenoswho was crowned co-emperor. Imitating the Campus in Rome, similar grounds were developed in several other urban centers and military settlements. The city also had several theatersgymnasiaand many tavernsbathsand brothels. The "In Trullo" or "Fifth-Sixth Council", known for its canons, was convened in the years of Justinian II — and occupied itself exclusively with matters of discipline. Live TV. Inthe barbarian Odoacer overthrew the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustusand Rome had fallen. They never absolutized natural rights or Roman law or even the Roman people. -

On the Application of Byzantine Law in Modern Bessarabia А

2021 ВЕСТНИК САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА Т. 12. Вып. 1 ПРАВО ПРАВОВАЯ ЖИЗНЬ: НАУЧНО-ПРАКТИЧЕСКИЕ ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЯ, КОММЕНТАРИИ И ОБЗОРЫ UDC 340.154:34.01 On the application of Byzantine law in modern Bessarabia А. D. Rudokvas, A. A. Novikov St. Petersburg State University, 7–9, Universitetskaya nab., St. Petersburg, 199034, Russian Federation For citation: Rudokvas, Anton D., Andrej A. Novikov. 2021. “On the application of Byzantine law in modern Bessarabia”. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Law 1: 205–223. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu14.2021.114 The article describes the application of Byzantine law in the region of Bessarabia which formed part of the Russian Empire from the early 19th century until 1917. The empire allowed the lo- cal population to apply their local laws for the regulation of their civil law relations. Due to historical reasons, these local laws were identified with the law of the Byzantine Empire which had already disappeared in 1453. The authors of the article provide a general description of the sources of Bessarabian law and then turn to case study research regarding the jurispru- dence of courts on the issues of the Law of Succession in Bessarabia. They demonstrate that in interpreting the provisions of the law applicable, Russian lawyers often referred to Roman law as a doctrinal background of Byzantine law. Furthermore, they did not hesitate to identify Roman law with Pandect law. Even though the doctrine of the Law of Pandects had been cre- ated in Germany on the basis of Roman law texts, it was far from the content of the original law of the Ancient Roman Empire. -

The Byzantine State and the Dynatoi

The Byzantine State and the Dynatoi A struggle for supremacy 867 - 1071 J.J.P. Vrijaldenhoven S0921084 Van Speijkstraat 76-II 2518 GE ’s Gravenhage Tel.: 0628204223 E-mail: [email protected] Master Thesis Europe 1000 - 1800 Prof. Dr. P. Stephenson and Prof. Dr. P.C.M. Hoppenbrouwers History University of Leiden 30-07-2014 CONTENTS GLOSSARY 2 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER 1 THE FIRST STRUGGLE OF THE DYNATOI AND THE STATE 867 – 959 16 STATE 18 Novel (A) of Leo VI 894 – 912 18 Novels (B and C) of Romanos I Lekapenos 922/928 and 934 19 Novels (D, E and G) of Constantine VII Porphyrogenetos 947 - 959 22 CHURCH 24 ARISTOCRACY 27 CONCLUSION 30 CHAPTER 2 LAND OWNERSHIP IN THE PERIOD OF THE WARRIOR EMPERORS 959 - 1025 32 STATE 34 Novel (F) of Romanos II 959 – 963. 34 Novels (H, J, K, L and M) of Nikephoros II Phokas 963 – 969. 34 Novels (N and O) of Basil II 988 – 996 37 CHURCH 42 ARISTOCRACY 45 CONCLUSION 49 CHAPTER 3 THE CHANGING STATE AND THE DYNATOI 1025 – 1071 51 STATE 53 CHURCH 60 ARISTOCRACY 64 Land register of Thebes 65 CONCLUSION 68 CONCLUSION 70 APPENDIX I BYZANTINE EMPERORS 867 - 1081 76 APPENDIX II MAPS 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY 82 1 Glossary Aerikon A judicial fine later changed into a cash payment. Allelengyon Collective responsibility of a tax unit to pay each other’s taxes. Anagraphis / Anagrapheus Fiscal official, or imperial tax assessor, who held a role similar as the epoptes. Their major function was the revision of the tax cadastre. It is implied that they measured land and on imperial order could confiscate lands.