Anna Komnene's Narrative of the War Against The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctoral Dissertation Márton Rózsa Byzantine Second-Tier Élite In

Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Humanities DOCTORAL DISSERTATION MÁRTON RÓZSA BYZANTINE SECOND-TIER ÉLITE IN THE ‘LONG’ TWELFTH CENTURY Doctoral School of History Head of the doctoral school: Dr. Gábor Erdődy Doctoral Programme of Medieval and Early Modern World History Head of the doctoral programme: Dr. Balázs Nagy Supervisor: Dr. Balázs Nagy Members of the assessment committee: Dr. István Draskóczy, Chair Dr. Gábor Thoroczkay, PhD, Secretary Dr. Floris Bernard, opponent Dr. Andreas Rhoby, opponent Dr. István Baán, member Dr. László Horváth, PhD, member Budapest, 2019 ADATLAP a d o kt ori ért e k e z é s n yit v á n o s s á gr a h a z at al á h o z l. A d o kt ori ért e k e z é s a d at ai A s z et z ő n e v e: Ró z s a ] u í árt o n MT M'f-azonosító: 1 0 0 1 9 2 7 0 A d o kt ori ért e k e z é s c í m e é s al c í m e: B y z a nti n e Second-Tie, Éttt ein t h e 'Lang'Tu,e\th C e nt ur y f) Ol-azonosító: 1 íl. l 5 1 7 6/ E L T E. 2 0 I 9. 0 5 ő A d o kt ori i s k ol a n e v e: Tü,t énele míuclo mányi D ol ú ori { sl ail a A d o kt ori pr o gr í } m n e v e: Köz é p k ori é s kora újkori e gt e í e m e s tört é n eti Doktori Progratn A t é mavezető n e v e ó s tudo mányos fcrkozata: § a g y * B ai ú z s. -

The Image of the Cumans in Medieval Chronicles

Caroline Gurevich THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES MA Thesis in Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis -

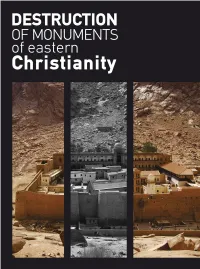

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

O. Karataev TITLE of the ANCIENT TURKS: “KAGAN” (QAGAN) and “ZHABGU” (YABGU)

ISSN 1563-0269, еISSN 2617-8893 Journal of history. №1 (96). 2020 https://bulletin-history.kaznu.kz IRSTI 03.29.00 https://doi.org/10.26577/JH.2020.v96.i1.02 O. Karataev Kastamonu University, Turkey, Kastamonu, е-mail: [email protected] TITLE OF THE ANCIENT TURKS: “KAGAN” (QAGAN) AND “ZHABGU” (YABGU) The Turks managed to create a huge empire. Territory – from the Altai mountains in the east to the Black Sea in the west, from the upper Yenisei in the north to the upper Amu Darya in the south. At the beginning of the VI century, the territory of Kazakhstan came under the authority of the Turkic Kaganate. Turkic Kaganate is the first state in Kazakhstan. Its basis was the union of Turkic-speaking tribes, which was headed by the kagan. The state, based on tribal traditions, was based on military-administrative management. It was part of a system of relations with such major states of the time as Iran and Byzan- tium. China was a tributary of the kaganate. The title in many cultures played the role of an important indicator of the international prestige of the state. As is known, only members of the Ashin clan had the sacred right to supreme power in the Turkic Kaganate. Possession of one or another title, occupation of one or another place in the political and state structure of society, depended on many circumstances, the main of which was belonging to a particular tribe in a tribal union, clan in a tribe, etc. Social deter- minants (titles, ranks, positions), as the most significant components of ancient Turkic anthroponomy, contained complete information about the social status of the bearer of a given name, its origin and membership in a particular layer of society, data on its place in the political structure of society and the administrative structure . -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

History of the Turkish People

June IJPSS Volume 2, Issue 6 ISSN: 2249-5894 2012 _________________________________________________________ History of the Turkish people Vahid Rashidvash* __________________________________________________________ Abstract The Turkish people also known as "Turks" (Türkler) are defined mainly as being speakers of Turkish as a first language. In the Republic of Turkey, an early history text provided the definition of being a Turk as "any individual within the Republic of Turkey, whatever his faith who speaks Turkish, grows up with Turkish culture and adopts the Turkish ideal is a Turk." Today the word is primarily used for the inhabitants of Turkey, but may also refer to the members of sizeable Turkish-speaking populations of the former lands of the Ottoman Empire and large Turkish communities which been established in Europe (particularly in Germany, France, and the Netherlands), as well as North America, and Australia. Key words: Turkish people. History. Culture. Language. Genetic. Racial characteristics of Turkish people. * Department of Iranian Studies, Yerevan State University, Yerevan, Republic of Armeni. A Monthly Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International e-Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage, India as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A. International Journal of Physical and Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us 118 June IJPSS Volume 2, Issue 6 ISSN: 2249-5894 2012 _________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction The Turks (Turkish people), whose name was first used in history in the 6th century by the Chinese, are a society whose language belongs to the Turkic language family (which in turn some classify as a subbranch of Altaic linguistic family. -

Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Galliker, Julia, "Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204)" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 27. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker, University of Michigan In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. Salvatore Gaspa, Cécile Michel, & Marie-Louise Nosch (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2017), pp. 346-373. -

Download the Full Document About Romania

About Romania Romania (Romanian: România, IPA: [ro.mɨni.a]) is a country in Southeastern Europe sited in a historic region that dates back to antiquity. It shares border with Hungary and Serbia to the west, Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova to the northeast, and Bulgaria to the south. Romania has a stretch of sea coast along the Black Sea. It is located roughly in the lower basin of the Danube and almost all of the Danube Delta is located within its territory. Romania is a parliamentary unitary state. As a nation-state, the country was formed by the merging of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859 and it gained recognition of its independence in 1878. Later, in 1918, they were joined by Transylvania, Bukovina and Bessarabia. At the end of World War II, parts of its territories (roughly the present day Moldova) were occupied by USSR and Romania became a member of Warsaw Pact. With the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Romania started a series of political and economic reforms that peaked with Romania joining the European Union. Romania has been a member of the European Union since January 1, 2007, and has the ninth largest territory in the EU and with 22 million people [1] it has the 7th largest population among the EU member states. Its capital and largest city is Bucharest (Romanian: Bucureşti /bu.kureʃtʲ/ (help·info)), the sixth largest city in the EU with almost 2 million people. In 2007, Sibiu, a large city in Transylvania, was chosen as European Capital of Culture.[2] Romania joined NATO on March 29, 2004, and is also a member of the Latin Union, of the Francophonie and of OSCE. -

The Oghuz Turks of Anatolia

THE OGHUZ TURKS OF ANATOLIA İlhan ŞAHİN The migration and settlement of Oghuz groups, who were also known as Turkmens in Anatolia, were closely related with the political and demographic developments in the Great Seljuk Empire. But in order to understand these developments better, it would be reasonable to dwell first a little on the conditions under which the Oghuz groups lived before migrating to Anatolia, and look to the reasons behind their inclination towards Anatolia. The Oghuz groups, who constituted an important part of the Göktürk and Uygur states, lived along the banks of the Sır Darya River and on the steppes lying to the north of this river in the first half of the tenth century1. Those were nomadic people, and they made a living out of stock breeding, so they needed summer pastures and winter quarters on which they had to raise their animals and survive through cold winter days comfortably. In addition to them, there were sedentary Oghuz groups. In those days, the sedentary Oghuz groups were called "yatuk"2 which means lazy. This indicates that leading a nomadic life was more favorable then. Although most of the Oghuz groups led a nomadic life, they did have a certain political and social structure and order. There are various views about the meaning of the word “Oghuz”, and according to dominant one among them, the word means “tribes”, and “union of tribes” or “union of relative tribes”3. So, in other words, the word had organizational and structural connotations in the political and social sense. The Oghuz groups, consisting of a number of different boys or tribes, can be examined in two main groups since the earlier periods in the most classical age of Prof. -

Lamentation, History, and Female Authorship in Anna Komnene’S Alexiad Leonora Neville

Lamentation, History, and Female Authorship in Anna Komnene’s Alexiad Leonora Neville NE OF THE MOST commonly read and widely available Byzantine histories is the Alexiad, a history of the em- Operor Alexios Komnenos, who ruled 1081–1118, by his daughter Anna Komnene (1083–1153). Anna’s first-hand descriptions of the passage of the First Crusade are frequently excerpted as expressing a paradigmatic ‘Byzantine view’ of the crusades. Although it is perhaps the most frequently read medieval Byzantine text, it is far from typical of Byzantine histories. Anna’s work is invariably called a history and she de- scribes herself explicitly as writing a history. Yet in its title, Alexiad, and frequent Homeric vocabulary and imagery, it brings the archaic epics to mind.1 The characterization of Alexios as a wily sea captain steering the empire through con- stant storms with guile and courage strongly recalls Odysseus.2 Both in its epic cast and in other factors discussed below, Anna did not adhere strictly to the rules of writing history and rather seems to have played with the boundaries of the genre. The 1 A. Dyck, “Iliad and Alexiad: Anna Comnena’s Homeric Reminiscences,” GRBS 27 (1985) 113–120. Anna’s husband, Nikephoros Bryennios, wrote a history of the rise of Alexios Komnenos in which Alexios ends up seeming less heroic than his political enemy Nikephoros Bryennios the elder (the author’s grandfather). At the point where Alexios has defeated Bryennios the elder, Nikephoros says that “another Iliad would be needed” to tell the deeds of his grandfather properly. -

The Ritualisation of Political Power in Early Rus' (10Th-12Th Centuries)

The Ritualisation of Political Power in Early Rus’ (10th-12th centuries) Alexandra Vukovic University of Cambridge Jesus College June 2015 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Preface Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration where specifically indicated in the text. No parts of this dissertation have been submitted for any other qualification. Statement of Length This dissertation does not exceed the word limit of 80,000 words set by the Degree Committee of the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages. Word count: 79, 991 words Alexandra Vukovic Abstract The Ritualisation of Political Power in Early Rus’ (10th-12th centuries) Alexandra Vukovic This dissertation examines the ceremonies and rituals involving the princes of early Rus’ and their entourage, how these ceremonies and rituals are represented in the literature and artefacts of early Rus’, the possible cultural influences on ceremony and ritual in this emergent society, and the role of ceremony and ritual as representative of political structures and in shaping the political culture of the principalities of early Rus’. The process begins by introducing key concepts and historiographic considerations for the study of ceremony and ritual and their application to the medieval world. The textological survey that follows focusses on the chronicles of Rus’, due to their compilatory nature, and discusses the philological, linguistic, and contextual factors governing the use of chronicles in this study. This examination of the ceremonies and rituals of early Rus’, the first comprehensive study of its kind for this region in the early period, engages with other studies of ceremony and ritual for the medieval period to inform our understanding of the political culture of early Rus’ and its influences. -

Iliad and Alexiad: Anna Comnena's Homeric Reminiscences Andrew R

DYCK, ANDREW R., "Iliad" and "Alexiad": Anna Comnena's Homeric Reminiscences , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 27:1 (1986:Spring) p.113 Iliad and Alexiad: Anna Comnena's Homeric Reminiscences Andrew R. Dyck HEN SCLERAENA, mistress of Constantine IX (regn. A.D. W 1042-1055), first entered the palace, one of the courtiers was heard to mutter ov lIE/J-EUIl;, an allusion to the comment of the Trojan elders when Helen mounted to their city's tower (II. 3.156f): ov lIE/J-EUtS TpWa~ Kat EVKlIT,f.U8a~ 'Axaw~ TOI:fi8' aJJ4X YVllal.Kt 7TOA:VlI XP01l01l aA'YEa 7TaUXEl.lI. Alas, the recipient of the compliment had to inquire as to its meaning. And no wonder: women of whatever position were not normally vouchsafed a classical educa tion in Byzantium. Even Styliane, the daughter of Michael Psellus (who retails this anecdote), had to begin her literary studies not with Homer, as a boy would, but with the Psalms.l Far different the case of Anna Comnena, whose Homeric learning is on display throughout her Alexiad. Yet if her confidant George Torni ces can be trusted, even she had to begin her studies of profane litera ture covertly, in the hours reserved for rest and sleep.2 Even the rare woman who ventured to break into the male realm of profane letters was by no means sure of receiving a fair hearing: consider the case of the woman who wrote a set of elementary grammatical notes (UXE8'YJ) for school instruction and received from John Tzetzes the ungallant advice to return to the spindle and distaff.3 Anna's, however, was an unusual ambition that bore fruit in an uncommon achievement.