'A New Heaven and a New Earth': the Making of the Cistercian Desert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuum: Laying a Foundation Winter 2008

Laying a foundation Between 1955 and 1958, the newly arrived Cistercians helped found the University of Dallas, carved out a piece of land, and built a monastery. By Brian Melton ’71 Editor’s note: This is the third in an occasional series of stories cel- Not that there was anything to complain about when it came to their ebratng the Cistercian’s 50 years in Texas. new digs in Texas. February found the fi rst seven monks (Frs. Damian Szödény, Thomas Fehér, Lambert Simon, Benedict Monostori, George, y 1955, things fi nally seemed to be going right for the Christopher Rábay, and Odo) living and working at Our Lady of Vic- beleaguered Hungarian Cistercians. Behind them lay tory in Fort Worth and several other parishes and schools throughout two intensely traumatic experiences: fi rst, their har- Dallas. And when Fr. Anselm Nagy came down from Wisconsin in the rowing escape from Soviet authorities back home, and spring, he established residence at the former Bishop Lynch’s stately second, the bitter disagreement with their own abbot mansion on Dallas’s tony Swiss Avenue (4946), which became the un- Bgeneral from Rome, Sighard Kleiner. His autocratic, imperious or- offi cial gathering place of his new little fl ock. ders for them — to live a life of contemplative farm work and prayer Even better, permission for a Cistercian residence in Dallas came at the tiny Spring Bank Monastery in Wisconsin — sat about as well straight from the Holy See and sailed effortlessly through the di- as the forced Soviet suppression of their beloved abbey back home ocesan attorney’s offi ce in March, as did the incipient monastery’s in Zirc (pronounced “Zeerts”), Hungary. -

A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St

Clemson University TigerPrints Master of Architecture Terminal Projects Non-thesis final projects 12-1986 A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield ounC ty, South Carolina Timothy Lee Maguire Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp Recommended Citation Maguire, Timothy Lee, "A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield County, South Carolina" (1986). Master of Architecture Terminal Projects. 26. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp/26 This Terminal Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Non-thesis final projects at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Architecture Terminal Projects by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MONASTERY FOR THE BROTHERS OF THE ORDER OF CISTERCIANS OF THE STRICT OBSERVANCE OF THE RULE OF ST. BENEDICT. Fairfield County, South Carolina A terminal project presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University in partial fulfillment for the professional degree Master of Architecture. Timothy Lee Maguire December 1986 Peter R. Lee e Id Wa er Committee Chairman Committee Member JI shimoto Ken th Russo ommittee Member Head, Architectural Studies Eve yn C. Voelker Ja Committee Member De of Architecture • ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . J Special thanks to Professor Peter Lee for his criticism throughout this project. Special thanks also to Dale Hutton. And a hearty thanks to: Roy Smith Becky Wiegman Vince Wiegman Bob Tallarico Matthew Rice Bill Cheney Binford Jennings Tim Brown Thomas Merton DEDICATION . -

The Defense of Monastic Memory in Bernard of Clairvaux’S

CORRECTING FAULTS AND PRESERVING LOVE: THE DEFENSE OF MONASTIC MEMORY IN BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX’S APOLOGIA AND PETER THE VENERABLE’S LETTER 28 A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts Whitney Mae Mihalik August, 2013 CORRECTING FAULTS AND PRESERVING LOVE: THE DEFENSE OF MONASTIC MEMORY IN BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX’S APOLOGIA AND PETER THE VENERABLE’S LETTER 28 Whitney Mae Mihalik Thesis Approved: Accepted: __________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Constance Bouchard Dr. Chand Midha __________________________________ _________________________________ Co-Advisor or Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Michael Graham Dr. George R. Newkome __________________________________ _________________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Martin Wainwright ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................1 II. HISTORIOGRAPHY ........................................................................................6 III. THE REFORMS OF BENEDICTINE MONASTICISM ...............................26 IV. BERNARD’S APOLOGIA ..............................................................................32 V. PETER’S LETTER 28 .....................................................................................58 VI. CONCLUSIONS..............................................................................................81 -

A Christian Understanding of Property: Spiritual Themes Underlying Western Property

A paper presented at the Pacific Rim Real Estate Conference, Melbourne, January 2005 A Christian Understanding of Property: Spiritual themes underlying Western property Garrick Small, PhD University of Technology, Sydney [email protected] Abstract: Interest in customary title has raised awareness of the cultural dependence of property and its relationship to spirituality. Western culture has a historical connection with Christian spirituality, yet its property institution is seldom related to it. Property is found within Christian thought from the very beginning of the Old Testament and shares several important commonalities with customary peoples. The notion of property is evident in the gospels along with repeated comments on the correct application of riches. Early Christianity can be viewed as a development of the Old Testament property institution consistent with other aspects of Christian moral thought. Changes in the institution of property through the Christian era can be seen to parallel changes in Christian thought eventually leading to present day property. Overall, property can be linked to the spiritual roots of Western culture in a manner that has the capacity to inform the development of dialogue with customary peoples in their endeavours to assert the validity of their property conventions. Keywords: property theory, customary title, moral theology, social economics, property and culture Introduction The current institution of property was initiated in the sixteenth century as the former conditional notion of private property was replaced by absolute property (Anderson 1979). That century also saw radical changes in other human institutions. Modernity began with Machiavelli’s (d.1527) option to replace classical realism with empiricism in political science1 (Machiavelli and Mansfield 1985). -

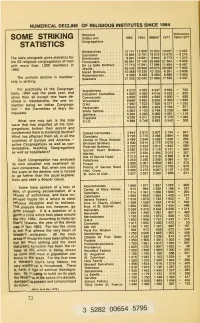

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

The Jesuits Founded on This Day, September 27, 1540

The Jesuits Founded on this day, September 27, 1540 I. Development of Religious “Orders” prior to the Jesuits Monastic -- ordinary and strict varieties (Benedictines, Carthusians, Cistercians, etc.) Western monasteries descend from Benedict of Nursia, + 547 Mendicant -- Dominicans (founded 1216) and Franciscans (founded 1209) Clerks Regular -- Renaissance development of organized groups of priests living together focused on pastoral care of people; they lived together under a common spiritual rule, becoming an effective method to reform local clergy II Iñigo de Loyola – Ignatius of Loyola (1493-1556) Early life as soldier, sickness, convalescence, period of intense & neurotic religiosity Discovery of spiritual “exercises”, determination to become a priest, study at Paris Formation of a group of colleagues, vows, idea of reaching the Holy Land Eventual arrival in Rome to offer themselves to whatever service the Pope desired Society of Jesus granted its existence September 27, 1540 Ignatius hereafter becomes an administrator of an ecclesiastical juggernaut III Discipline and Flexibility as the marks of the order •How do they live together? They don’t, necessarily. They travel a lot (at least corporately). •What do Jesuits do? Whatever needs doing or whatever special mission the Pope assigns. •Variety of Jesuit ministries: education of lay people; education of clergy; global missions; parish work; research; communication; spiritual retreats; writing •How did the Jesuits found schools and universities? (27 in USA) (Joke about Bethlehem) IV Significant moments Adherence to social elites, wealth, influence, and eventual suppression of the Order (1773) (My landlady in Dublin; McCann’s Grandmother) Expulsion of Jesuits from France, Spain, Portugal 1757-1770 Revival of Order (1814) and strict adherence to the Papacy Liberalization of the Order in the 1900s and criticism of Vatican (1970s), reined in by Pope (1980s) V Reformulation of the Jesuits’ Mission, 1975: heightened focus on social justice (Examples: El Salvador, Nicaragua) (Example Cristo Rey Network) “ . -

Jesuit Urban Mission

Jesuit Urban Mission Bernard loved the hills, Benedict the valleys, Francis the towns, Ignatius great cities. This brief couplet of unknown origin captures in a few words the distinct charisms of four saints and founders of religious communities in the Church— the Cistercians, the Benedictines, the Franciscans and the Jesuits. Ignatius of Loyola, who founded the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), placed much focus on the plight of the poor in the great cities of his time. In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius imagined God gazing upon the teeming masses of our cities, on men and women sick and dying, the old and young, the rich and the poor, the happy and sad, some being born and some being laid to rest. Surrounded by that mass of human need, Ignatius was 63 moved by a God who joyfully opted to 60 At Rome he founds public works of piety: hospices for In Rome, he renews the practice of frequenting women in bad marriages; for virgins at [the church of] step into the pain of human suffering and the sacraments and of giving devout sermons and Santa Caterina dei Funari, for [orphan] girls at [the became flesh, sharing fully all our human introduces ways of passing on the rudiments of church of] Santi Quattro Coronati, also for orphan Christian doctrine to youth in the churches and boys wandering through the city as beggars, a residence joys and sorrows. squares of Rome. Peter Balais, S.J. Plates 60, 63. Vita beati patris Ignatii Loiolae for [Jewish] catechumens, as well as other residences The Illustrated Life of Ignatius of Loyola, and colleges, to the profit and with the admiration of Jesuit Refugee Service published in Rome in 1609 to celebrate Ignatius’ beatification that year by Pope Paul V. -

May 26, 2000 Vol

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 4, 5 Editorial. 4 From the Archives. 25 Question Corner . 11 TheCriterion Sunday & Daily Readings. 11 Criterion Vacation/Travel Supplement . 13 Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 www.archindy.org May 26, 2000 Vol. XXXIX, No. 33 50¢ Two men to be ordained to the priesthood By Margaret Nelson His first serious study of religion was of 1979—four months into the Iran civil his sister and her husband when he was 6 Islam, when he began to teach in Saudi war. years old. Archbishop Daniel M. Buechlein will Arabia. A history professor there, “a wise “I approached the nearest Catholic At his confir- ordain two men to the priesthood for the man from Iraq” who spoke fluent English, Church—St. Joan of Arc in Indianapolis.” mation in 1979, Archdiocese of Indianapolis at 11 a.m. on talked with him He asked Father Donald Schmidlin for Borders didn’t June 3 at SS. Peter and Paul Cathedral in about his own instructions. Since that was before the think of the Indianapolis. faith. Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults priesthood. He They are Larry Borders of St. Mag- “He knew process was so widespread, he met with had been negoti- dalen Parish in New Marion—who spent more about the priest and two other men every week ating a teaching two decades overseas teaching lan- Christianity than or so. job in Japan to guages—and Russell Zint of St. Monica I knew about The week before Christmas in 1979, begin a 15-year Parish in Indianapolis—who studied engi- my own tradi- Borders was confirmed into the Catholic contract. -

John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2019 Exercising Obedience: John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity Joshua Daniel Schachterle University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Schachterle, Joshua Daniel, "Exercising Obedience: John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1615. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1615 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Exercising Obedience: John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology Joint PhD Program In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Joshua Daniel Schachterle June 2019 Advisor: Gregory Robbins PhD © by Joshua Daniel Schachterle All Rights Reserved Author: Joshua Daniel Schachterle Title: Exercising Obedience: John Cassian and the Creation of Early Monastic Subjectivity Advisor: Gregory Robbins PhD Date: June 2019 Abstract John Cassian (360-435 CE) started his monastic career in Bethlehem. He later traveled to the Egyptian desert, living there as a monk, meeting the venerated Desert Fathers, and learning from them for about fifteen years. Much later, he would go to the region of Gaul to help establish a monastery there by writing monastic manuals, the Institutes and the Conferences. -

Of the Desert Fathers. the Relationship with the Other in Apophthegmata Patrum

The “Ecumenism” of the Desert Fathers. The Relationship with the Other in Apophthegmata Patrum Paul Siladi* Ecumenism is a 20th century concept that cannot be directly transposed in the everyday reality of the Desert Fathers, but the authority of the desert ascetics is still crucial to the monastic milieu of the Orthodox Church as well as other denominations. For this very reason, the present paper intends to investigate the stories recorded in the alphabetical collection of the Egyptian Paterikon in order to understand to what extent they may actually offer a guide to the complex relations with the Other. How do these stories illustrate denominational or even religious alterity? What types of rapports can one identify therein? Rejection? Separation? Acceptance of the other’s difference? These are all legitimate questions and their significance is amplified in the context of our times – a period in which we see an increase in fundamentalist movements and tendencies, including in the Orthodox community. Keywords: Ecumenism, Desert Fathers, Paterikon, Apophthegmata Patrum, asceticism, spirituality. The recent concept of ecumenism dates back to the beginning of the 20th century and as such it would be difficult to transfer it into the reality of the every-day lives of the Desert Fathers. Even so the ancient ascetics of the desert still exert significant authority in the Orthodox monastic milieus and not only there; for this very reason the present paper sets out to investigate the stories recorded in the alphabetical collection of the Egyptian Paterikon in order to see if they may contain elements for a guide to relationships marked by confessional1 or religious alterity. -

THE SAYINGS of the DESERT FATHERS

Selections From THE SAYINGS Of THE DESERT FATHERS With Kind Permission Of Cistercian Publication Title of the book - The Sayings of the Desert Fathers Name of the translator - Sister Benedicta Ward SLG Publisher - Cistercian Publication Address of the published - WMU Station, Kalamazoo, Michigan 19008/USA Copyright, 1975 2 Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ King of Kings and Lord of lords Icon designed by Dr. Yousef Nassief and Dr. Bedour Latif H.H. Pope Shenouda III, 117th Pope of Alexandria and the See of St. Mark ABBA ANTHONY THE GREAT Anthony the Great, called 'The Father of Monks' was born in central Egypt about AD the son of peasant farmers who were Christian. In c. 269 he heard the Gospel read in church and applied to himself the words. 'Go, sell all that you have and give to the poor and come . .’ He devoted himself to a life of asceticism under the guidance of a recluse near his village. In c. 285 he went alone into the desert to live in complete solitude. His reputation attracted followers, who settled near him, and in c. 305 he came out of his hermitage in order to act as their spiritual father. Five years later he again retired into solitude. He visited Alexandria at least twice. Once during the persecution of Christians and again to support the Bishop Athanasius against heresy. He died at the age of one hundred and five. His life was written by Saint Athanasius and was very influential in spreading the ideals of monasticism throughout the Christian World. 1. -

How to Address Priests and Religious: Titles and Signs of Respect

How to Address Priests and Religious: Titles and Signs of Respect Marian Therese Horvat, Ph.D. Before me are several interesting questions on how we should address priests and religious men and women sent to my desk recently by a lady. I will answer them today on the TIA website, since I think that my correspondent is not the only one with similar queries. In times past every Catholic used to know some of the simple rules that have been set aside from disuse. The general protocol was taught by sisters in grade school, but more often was learned as in osmosis from everyday practice. No one dreamed of calling Father O’Reilly by the nickname “Bill,” or, addressing Sister Margaret Mary as “Maggie.” Everyone knew you rose as a sign of respect when a priest or religious entered the room. Speaking before a gathering that included clergy or religious, a Catholic speaker as habit addressed them solemnly first. The dignified sisters inspired respect. Above, a sister teaches protocol in a pre-Vatican II Catholic classroom. But then came the tumultuous and leveling aftermath of Vatican II that spelled a death to formalities in the religious sphere. Priests, monks and sisters began to adopt the ways of a world that were becoming increasingly vulgar and egalitarian. Distinguishing titles and marks of respect were considered alienating and only for old- fashioned “establishment” people who were afraid to embrace the “signs of the times.” In the spirit of adaptation to the world, the cassock and habit were abandoned, along with the formal signs of respect paid to the persons who wore them.