Twelfth-Century Cistercian and Premonstratensian Teachings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuum: Laying a Foundation Winter 2008

Laying a foundation Between 1955 and 1958, the newly arrived Cistercians helped found the University of Dallas, carved out a piece of land, and built a monastery. By Brian Melton ’71 Editor’s note: This is the third in an occasional series of stories cel- Not that there was anything to complain about when it came to their ebratng the Cistercian’s 50 years in Texas. new digs in Texas. February found the fi rst seven monks (Frs. Damian Szödény, Thomas Fehér, Lambert Simon, Benedict Monostori, George, y 1955, things fi nally seemed to be going right for the Christopher Rábay, and Odo) living and working at Our Lady of Vic- beleaguered Hungarian Cistercians. Behind them lay tory in Fort Worth and several other parishes and schools throughout two intensely traumatic experiences: fi rst, their har- Dallas. And when Fr. Anselm Nagy came down from Wisconsin in the rowing escape from Soviet authorities back home, and spring, he established residence at the former Bishop Lynch’s stately second, the bitter disagreement with their own abbot mansion on Dallas’s tony Swiss Avenue (4946), which became the un- Bgeneral from Rome, Sighard Kleiner. His autocratic, imperious or- offi cial gathering place of his new little fl ock. ders for them — to live a life of contemplative farm work and prayer Even better, permission for a Cistercian residence in Dallas came at the tiny Spring Bank Monastery in Wisconsin — sat about as well straight from the Holy See and sailed effortlessly through the di- as the forced Soviet suppression of their beloved abbey back home ocesan attorney’s offi ce in March, as did the incipient monastery’s in Zirc (pronounced “Zeerts”), Hungary. -

Fables of King Arthur

MIRATOR 9:1 (2008) 19 Fables of King Arthur Aelred of Rievaulx and Secular Pastimes Jaakko Tahkokallio Introduction This article sets out to contextualise the famous Arthurian anecdote found in the Speculum Caritatis by Aelred of Rievaulx (c. 1110–1167) on two different levels. Firstly, I shall offer an analysis of the immediate textual context of this controversial passage, by which I wish to demonstrate that it is best interpreted as a reference to orally circulated stories, not to the Latin history of Geoffrey of Monmouth, as has often been argued. Secondly, I explore the ways in which Aelred speaks of storytelling and other secular pastimes elsewhere in his works, since I understand that his more general views on these topics provide important contextual information for the interpretation of the Arthurian anecdote. Doing this, I wish to emphasise how the anecdote is related to communication with monks who were probably strongly associated with lay aristocratic culture, and how, in consequence, the passage is all the more likely to refer to forms of vernacular storytelling pertaining to the settings of secular life. Furthermore, I shall address the issue of how Aelred, contrasting monastic and secular ways of life, invoked the views of St. Augustine on pagan theatre, entertainers, and poetry. I shall briefly examine the relationship between the ideas of these two writers, and argue that Aelred used St. Augustine's ideas not only because they were topoi of a literary tradition in which he was writing, but because he found them useful in his analysis of contemporaneous cultural phenomena, even though these were certainly very different from those St. -

Profile Aelred of Rievaulx

KNOWING & DOING A Teaching Quarterly for Discipleship of Heart and Mind This article originally appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Knowing & Doing. C.S. LEWIS INSTITUTE PROFILES IN FAITH Aelred of Rievaulx (1110-1167) Friend and Counselor by James M. Houston Senior Fellow, C.S. Lewis Institute Founder of Regent College, Professor of Spiritual Theology (retired), and Lecturer at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford University elred of Rievaulx was born at Hexham, No, no, I beg; no, my sons, do not strip your father of an area considered remote in today’s the vesture of suffering. I am quite all right, I am not England, but a rich cultural center of hurt, I am not upset; this son of mine who threw me Northumbria in his day. Neither Eng- into the fire, has cleansed, not destroyed me. He is my AA lish nor Scottish in its independence, its son, but he is ill. I am indeed not sound of body, but he frontier character enabled Aelred’s family to exert in his sickness has made me sound in soul, for blessed ecclesial influence over both countries as devout and are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the sons godly priests. With such moral exemplars, it is under- of God’. And then taking his head in his hands, the standable that priestly celibacy, enforced elsewhere most blessed man kisses him, blesses and embraces by the Gregorian Reform, was so slow in entering him, and gently sought to soothe his senseless anger into their realm of influence; it must have seemed against himself, just as though he felt no pain from unnecessary. -

October 2017

St. Mary of the St. Vincent’s ¿ En Que Consiste Angels School Welcomes El Rito Del Ukiah Religious Sisters Exorcismo? Page 21 Page 23 Pagina 18 NORTH COAST CATHOLIC The Newspaper of the Diocese of Santa Rosa • www.srdiocese.org • OCTOBER 2017 Noticias en español, pgs. 18-19 Pope Francis Launches Campaign to Encounter and Since early May Catholics around the diocese have been celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Apparitions of Our Welcome Migrants Lady of the Most Holy Rosary in Fatima. The Rosary: The Peace Plan by Elise Harris from Heaven Catholics are renewing Mary’s Rosary devotion as the Church commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Fatima apparitions by Peter Jesserer Smith (National Catholic Register) “Say the Rosary every day to bring peace to the world promised as the way to end the “war to end all wars.” and the end of the war.” The great guns of World War I have fallen silent, but One hundred years ago at a field in Fatima, Por- these words of Our Lady of the Rosary have endured. tugal, the Blessed Virgin Mary spoke those words to In this centenary year of Our Lady’s apparitions at three shepherd children. One thousand miles away, Fatima, as nations continue to teeter toward war and in the bloodstained fields of France, Europe’s proud strife, Catholics have been making a stronger effort to empires counted hundreds of thousands of their spread the devotion of the Rosary as a powerful way “Find that immigrant, just one, find out who they are,” youth killed and wounded in another battle vainly (see The Rosary, page 4) she said. -

A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St

Clemson University TigerPrints Master of Architecture Terminal Projects Non-thesis final projects 12-1986 A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield ounC ty, South Carolina Timothy Lee Maguire Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp Recommended Citation Maguire, Timothy Lee, "A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield County, South Carolina" (1986). Master of Architecture Terminal Projects. 26. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp/26 This Terminal Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Non-thesis final projects at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Architecture Terminal Projects by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MONASTERY FOR THE BROTHERS OF THE ORDER OF CISTERCIANS OF THE STRICT OBSERVANCE OF THE RULE OF ST. BENEDICT. Fairfield County, South Carolina A terminal project presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University in partial fulfillment for the professional degree Master of Architecture. Timothy Lee Maguire December 1986 Peter R. Lee e Id Wa er Committee Chairman Committee Member JI shimoto Ken th Russo ommittee Member Head, Architectural Studies Eve yn C. Voelker Ja Committee Member De of Architecture • ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . J Special thanks to Professor Peter Lee for his criticism throughout this project. Special thanks also to Dale Hutton. And a hearty thanks to: Roy Smith Becky Wiegman Vince Wiegman Bob Tallarico Matthew Rice Bill Cheney Binford Jennings Tim Brown Thomas Merton DEDICATION . -

Heritage at Risk Register 2014, East Midlands

2014 HERITAGE AT RISK 2014 / EAST MIDLANDS Contents Heritage at Risk III Nottinghamshire 58 Ashfield 58 The Register VII Bassetlaw 59 Broxtowe 63 Content and criteria VII Gedling 64 Criteria for inclusion on the Register VIII Mansfield 65 Reducing the risks X Newark and Sherwood 65 Rushcliffe 68 Key statistics XIII Rutland (UA) 69 Publications and guidance XIV Key to the entries XVI Entries on the Register by local planning XVIII authority Derby, City of (UA) 1 Derbyshire 2 Amber Valley 2 Bolsover 3 Chesterfield 4 Derbyshire Dales 5 High Peak 6 North East Derbyshire 8 Peak District (NP) 9 South Derbyshire 9 Leicester, City of (UA) 12 Leicestershire 15 Blaby 15 Charnwood 15 Harborough 17 Hinckley and Bosworth 19 Melton 20 North West Leicestershire 21 Lincolnshire 22 Boston 22 East Lindsey 24 Lincoln 32 North Kesteven 33 South Holland 36 South Kesteven 39 West Lindsey 44 Northamptonshire 49 Daventry 49 East Northamptonshire 52 Kettering 53 Northampton 54 South Northamptonshire 54 Wellingborough 56 Nottingham, City of (UA) 57 II EAST MIDLANDS Heritage at Risk is our campaign to save listed buildings and important historic sites, places and landmarks from neglect or decay. At its heart is the Heritage at Risk Register, an online database containing details of each site known to be at risk. It is analysed and updated annually and this leaflet summarises the results. Over the past year we have focused much of our effort on assessing listed Places of Worship; visiting those considered to be in poor or very bad condition as a result of local reports. -

RIEVAULX ABBEY and ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia

RIEVAULX ABBEY AND ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia Maria JAMROZIAK Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr Wendy Childs for her continuous help and encouragement at all stages of my research. I would also like to thank other faculty members in the School of History, in particular Professor David Palliser and Dr Graham Loud for their advice. My thanks go also to Dr Mary Swan and students of the Centre for Medieval Studies who welcomed me to the thriving community of medievalists. I would like to thank the librarians and archivists in the Brotherton Library Leeds, Bodleian Library Oxford, British Library in London and Public Record Office in Kew for their assistance. Many people outside the University of Leeds discussed several aspects of Rievaulx abbey's history with me and I would like to thank particularly Dr Janet Burton, Dr David Crouch, Professor Marsha Dutton, Professor Peter Fergusson, Dr Brian Golding, Professor Nancy Partner, Dr Benjamin Thompson and Dr David Postles as well as numerous participants of the conferences at Leeds, Canterbury, Glasgow, Nottingham and Kalamazoo, who offered their ideas and suggestions. I would like to thank my friends, Gina Hill who kindly helped me with questions about English language, Philip Shaw who helped me to draw the maps and Jacek Wallusch who helped me to create the graphs and tables. -

River Witham the Source of the 8Th Longest River Wholly in England Is

River Witham The source of the 8th longest river wholly in England is just outside the county, Lincolnshire, through which it follows almost all of a 132km course to the sea, which is shown on the map which accompanies Table Wi1 at the end of the document. Three kilometres west of the village of South Witham, on a minor road called Fosse Lane, a sign points west over a stile to a nature reserve. There, the borders of 3 counties, Lincolnshire, Rutland and Leicestershire meet. The reserve is called Cribb’s Meadow, named for a famous prize fighter of the early 19th century; at first sight a bizarre choice at such a location, though there is a rational explanation. It was known as Thistleton Gap when Tom Cribb had a victory here in a world championship boxing match against an American, Tom Molineaux, on 28th September 1811; presumably it was the only time he was near the place, as he was a Bristolian who lived much of his life in London. The organisers of bare-knuckle fights favoured venues at such meeting points of counties, which were distant from centres of population; they aimed to confuse Justices of the Peace who had a duty to interrupt the illegal contests. Even if the responsible Justices managed to attend and intervene, a contest might be restarted nearby, by slipping over the border into a different jurisdiction. In this fight, which bore little resemblance to the largely sanitised boxing matches of today, it is certain that heavy blows were landed, blood was drawn, and money changed hands, before Cribb won in 11 rounds; a relatively short fight, as it had taken him over 30 rounds to beat the same opponent at the end of the previous year to win his title. -

Year XCII - April 2014 - N

CHAR ITAS SERVantS Of ChaRity: RESERVEd publiCatiOn REFLECTIONS ON “CHARITAS” THE CONGREGATION’S TASK OF FORMATION LIFE IN THE SPIRIT AND THE PATH OF HOLINESS THE SPIRIT OF PROVIDENCE COMMUNICATIONS DECREES DECEASED CONFRERES Editing Office: Generalate - Vicolo Clementi, 41 - 00148 Rome Y E ear X ngli CII sh E - Ap ditio ril 20 n 14 - N . 230 chari tas n. 230 reserved to the servants of charity year Xcii - april 2014 *** 1 *** *** 2 *** Table of contents letter from the superior general reflections on “charitas” 5 • The Congregation’s task of formation edited by fr. alfonso crippa, superior general 8 insights • Life in spirit and the path of holiness by msgr. mario Jorge Bergoglio, auxiliary bishop of Buenos aires 18 • The spirit of Providence edited by fr. tito credaro 35 communications a. confreres 48 B. events of consecration 51 decrees 1. decree on holidays 54 2. decrees of erection of new communities and residences 56 3. appointments 62 4. “nulla osta” for appointments 62 5. “nulla osta” to take on parishes or institutes 64 6. “nulla osta” for the alienation of properties and projects requiring the authorization of the superior general 65 7. changes of province 65 8. leaving the congregation - exclaustration permissions 66 3 deceased confreres 1. fr. alfredo vincenzo rossetti 68 2. fr. mario sala 71 3. fr. pietro scano 73 4. fr. luigi romanò 88 4 LETTERLETTER OFOF THETHE SUPERIORSUPERIOR GENERALGENERAL REFLECTIONS ON “CHARITAS” Dear confreres, The main purpose of our customary annual distribution of Charitas is to recall the events of a year in the Congregation’s life and to report the main activities of the General Government. -

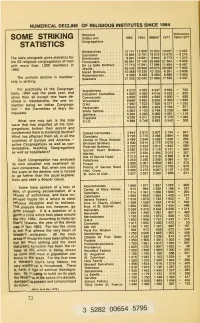

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

The Jesuits Founded on This Day, September 27, 1540

The Jesuits Founded on this day, September 27, 1540 I. Development of Religious “Orders” prior to the Jesuits Monastic -- ordinary and strict varieties (Benedictines, Carthusians, Cistercians, etc.) Western monasteries descend from Benedict of Nursia, + 547 Mendicant -- Dominicans (founded 1216) and Franciscans (founded 1209) Clerks Regular -- Renaissance development of organized groups of priests living together focused on pastoral care of people; they lived together under a common spiritual rule, becoming an effective method to reform local clergy II Iñigo de Loyola – Ignatius of Loyola (1493-1556) Early life as soldier, sickness, convalescence, period of intense & neurotic religiosity Discovery of spiritual “exercises”, determination to become a priest, study at Paris Formation of a group of colleagues, vows, idea of reaching the Holy Land Eventual arrival in Rome to offer themselves to whatever service the Pope desired Society of Jesus granted its existence September 27, 1540 Ignatius hereafter becomes an administrator of an ecclesiastical juggernaut III Discipline and Flexibility as the marks of the order •How do they live together? They don’t, necessarily. They travel a lot (at least corporately). •What do Jesuits do? Whatever needs doing or whatever special mission the Pope assigns. •Variety of Jesuit ministries: education of lay people; education of clergy; global missions; parish work; research; communication; spiritual retreats; writing •How did the Jesuits found schools and universities? (27 in USA) (Joke about Bethlehem) IV Significant moments Adherence to social elites, wealth, influence, and eventual suppression of the Order (1773) (My landlady in Dublin; McCann’s Grandmother) Expulsion of Jesuits from France, Spain, Portugal 1757-1770 Revival of Order (1814) and strict adherence to the Papacy Liberalization of the Order in the 1900s and criticism of Vatican (1970s), reined in by Pope (1980s) V Reformulation of the Jesuits’ Mission, 1975: heightened focus on social justice (Examples: El Salvador, Nicaragua) (Example Cristo Rey Network) “ . -

Jesuit Urban Mission

Jesuit Urban Mission Bernard loved the hills, Benedict the valleys, Francis the towns, Ignatius great cities. This brief couplet of unknown origin captures in a few words the distinct charisms of four saints and founders of religious communities in the Church— the Cistercians, the Benedictines, the Franciscans and the Jesuits. Ignatius of Loyola, who founded the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), placed much focus on the plight of the poor in the great cities of his time. In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius imagined God gazing upon the teeming masses of our cities, on men and women sick and dying, the old and young, the rich and the poor, the happy and sad, some being born and some being laid to rest. Surrounded by that mass of human need, Ignatius was 63 moved by a God who joyfully opted to 60 At Rome he founds public works of piety: hospices for In Rome, he renews the practice of frequenting women in bad marriages; for virgins at [the church of] step into the pain of human suffering and the sacraments and of giving devout sermons and Santa Caterina dei Funari, for [orphan] girls at [the became flesh, sharing fully all our human introduces ways of passing on the rudiments of church of] Santi Quattro Coronati, also for orphan Christian doctrine to youth in the churches and boys wandering through the city as beggars, a residence joys and sorrows. squares of Rome. Peter Balais, S.J. Plates 60, 63. Vita beati patris Ignatii Loiolae for [Jewish] catechumens, as well as other residences The Illustrated Life of Ignatius of Loyola, and colleges, to the profit and with the admiration of Jesuit Refugee Service published in Rome in 1609 to celebrate Ignatius’ beatification that year by Pope Paul V.