River Witham the Source of the 8Th Longest River Wholly in England Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.2 North Kesteven Sites Identified Within North Kesteven Local Authority Area

Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 4.2 North Kesteven Sites identified within North Kesteven local authority area. Page 1 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 Page 2 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 North Kesteven DC SHLAA Map CL1418 Reference Site Address Land off North Street, Digby Site Area (ha) 0.31 Ward Ashby de la Launde and Cranwell Parish Digby Estimated Site 81 Capacity Site Description Greenfield site in agricultural use, within a settlement. Listed Building in close proximity. The inclusion of this site or any other sites in this document does not represent a decision by the Central Lincolnshire authorities and does not provide the site with any kind of planning status. Page 3 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 Map CL1418 http://aurora.central- lincs.org.uk/map/Aurora.svc/run?script=%5cShared+Services%5cJPU%5cJPUJS.AuroraScri pt%24&nocache=1206308816&resize=always Page 4 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 North Kesteven SHLAA Map CL432 Reference Site Address Playing field at Cranwell Road, Cranwell Site Area (ha) 0.92 Ward Ashby de la Launde and Cranwell Parish Cranwell & Byard's Leap Estimated Site 40 Capacity Site Description Site is Greenfield site. In use as open space. Planning permission refused (05/0821/FUL) for 32 dwellings. The inclusion of this site or any other sites in this document does not represent a decision by the Central Lincolnshire authorities and does not provide the site with any kind of planning status. -

Lincolnshire

A guide to the lndustrial Archaeology of LINGOLilSHIRE including South Humberside by Neil R Wright r nrr r,..ll.,. L a € 6 ! s x Published by the Association for lndustrial Archaeology and The Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology A guide to the lndustrial Archaeology ot arE in dangEr o{ demolition and rnay have gone before you get lh€re, but iI this booklet succ€€ds TINCOLilSHIRE in increasing interest ard kno/vl€dge thon it will have seryed one of its purposes. including South Humberside Wirdmills, wa$rmills and sonE oth€r sites contain workino rnachinery ard it should always be rernembercd that sudl m&hinory is dangerors and you shou ld td(. v.iy !..n c.lt The FrrpG€ ol this booklet is to draw attention in srctr buildingF- to sorne ol the sites of industrial archasological Lincolnshire was, ard still is, rnainly an agri interest in a counv whict was the s€cond largest otlturalcounty. But s€veral to /ns b€canE ln Engl6nd. This guid6 includes museurns which industrialized, and in the countryside th6rc havecollections of industrial nrat€rial and $rere wind and warcr mills, brickyards, a felv prsso €d iadustrial buildings Many ot the quarries and other premis€s processing local sites ar€ on prival€ prop€rty and although the nraterials and producing ooods for Iocal e)<tario.s c6n genqally be vie\ /ed {rom a public consumption. right of way. access to them is by courtesy of L.incolnshire's role in the lrdustrial the owners and in sonE cases an appointment is Bevolution was to supply food, wool and n€€dod. -

Display PDF in Separate

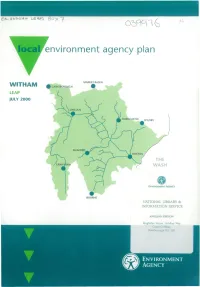

^ / v^/ va/g-uaa/ Ze*PS o b ° P \ n & f+ local environment agency plan WITHAM LEAP JULY 2000 NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House, Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay, ▼ Peterborough PE2 SZR T En v ir o n m e n t Ag e n c y T KEY FACTS AND STATISTICS Total Area: 3,224 km2 Population: 347673 Environment Agency Offices: Anglian Region (Northern Area) Lincolnshire Sub-Office Waterside House, Lincoln Manby Tel: (01522) 513100 Tel: (01507) 328102 County Councils: Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire District Councils: West Lindsey, East Lindsey, North Kesteven, South Kesteven, South Holland, Newark & Sherwood Borough Councils: Boston, Melton Unitary Authorities: Rutland Water Utility Companies: Anglian Water Services Ltd, Severn Trent Water Ltd Internal Drainage Boards: Upper Witham, Witham First, Witham Third, Witham Fourth, Black Sluice, Skegness Navigation Authorities: British Waterways (R.Witham) 65.4 km Port of Boston (Witham Haven) 10.6 km Length of Statutory Main River: 633 km Length of Tidal Defences: 22 km Length of Sea Defences: 20 km Length of Coarse Fishery: 374 km Length of Trout Fishery: 34 km Water Quality: Bioloqical Quality Grades 1999 Chemical Qualitv Grades 1999 Grade Length of River (km) Grade Length of River (km) "Very Good" 118.5 "Very Good" 11 "Good" 165.9 "Good" 111.6 "Fairly Good" 106.2 "Fairly Good" 142.8 "Fair" 8.4 "Fair" 83.2 "Poor" 0 "Poor" 50.4 "Bad" 0 "Bad" 0 Major Sewage Treatment Works: Lincoln, North Hykeham, Marston, Anwick, Boston, Sleaford Integrated Pollution Control Authorisation Sites: 14 Sites of Special Scientific Interest: 39 Sites of Nature Conservation Interest: 154 Nature Reserves: 12 Archaeological Sites: 199 Licensed Waste Management Facilities: La n d fill: 30 Metal Recycling Facilities: 16 Storage and Transfer Facilities: 35 Pet Crematoriums: 2 Boreholes: 1 Mobile Plants: 1 Water Resources: Mean Annual Rainfall: 596.7 mm Total Cross Licensed Abstraction: 111,507 ml/yr % Licensed from Groundwater = 32 % % Licensed from Surface Water = 68 % Total Gross Licensed Abstraction: Total no. -

The Grange| Tattershall | Lincolnshire | LN4 4LR Region of £750,000

The Grange| Tattershall | Lincolnshire | LN4 4LR Region of £750,000 COUNTRY HOMES COTTAGES UNIQUE PROPERTIES CONVERSIONS PERIOD PROPERTIES LUXURY APARTMENTS North Lincolnshire The Grange, Tattershall, Lincolnshire, LN4 4LR. This outstanding 5 bedroom Georgian style property stands in approximately 1 acre of attractive, landscaped and walled gardens, allowing gated access onto a further 2 ½ acres of grass paddock land with additional equestrian facilities. ‘The Grange’ is a fine Georgian style residence that benefits from a secluded and private plot within a delightful position of the village of Tattershall. The village offers a wide range of amenities to include a Primary School, Post Office, Super Market, a range of Local Shops and a Leisure Park. Tattershall has close links to the larger towns of Woodhall Spa, Boston and Horncastle. The property enjoys a view of Tattershall Castle and Holy Trinity Church. ‘The Grange’ is approached by a long sweeping driveway with entrance and exit gates and is surrounded by a mature, walled gardens of approximately one acre. The house offers spacious, family accommodation. A delightful Portico leads through the front door to: The Entrance Hall 23’11 x 9’11 A spacious entrance hall with doors leading to the ground floor rooms and stairs rising to the first floor. The Lounge 22’9 x 15’11 A spacious room that is full of light and appreciating a southerly aspect with views across the garden. A central focal point of The Lounge is an open fireplace with a marble base and a wood surround. There are three floor to ceiling sash windows and a glazed door which provides access to the garden. -

![Itinerary for Cheshire Ring (Clockwise) Starting at Nantwich Basin [Off the Ring] Page 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3980/itinerary-for-cheshire-ring-clockwise-starting-at-nantwich-basin-off-the-ring-page-1-143980.webp)

Itinerary for Cheshire Ring (Clockwise) Starting at Nantwich Basin [Off the Ring] Page 1

Itinerary for Cheshire Ring (clockwise) starting at Nantwich Basin [off the ring] Page 1 Cheshire Ring (clockwise) starting at Nantwich Basin [off the ring] (Itinerary from Nantwich Basin to Nantwich Basin via Middlewich Junction, Preston Brook - Waters Meeting, Marple Junction and Middlewich Junction) The original waterways ring, and the site of some critical early canal restoration this ring runs through the open Cheshire countryside, the vibrant heart of modern Manchester and the chemical industries of Northwich - something for everyone! This is calculated based on 7 full days travelling. Each full day will be approximately 9 hours and 9 minutes cruising First day of trip Go to day 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 You will be travelling from Nantwich Basin to Northwich Chemical Works, which is 19.96 miles and 8 locks This is 9 hours 11 minutes travelling Shropshire Union Canal (Chester Canal) 0.41 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable (total 0.41 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable Acton Bridge No 93. bridges bridges ) Henhull Bridge No 95. 0.59 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable (total 1 mile, 0 locks, 0 moveable A51(T) road. bridges bridges ) 0.36 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable (total 1.36 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable Poole Hill Pipe Bridge. bridges bridges ) 0.08 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable (total 1.44 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable Poole Hill Winding Hole. bridges bridges ) 0.19 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable (total 1.62 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable Cornes Bridge No 96. bridges bridges ) 0.24 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable (total 1.86 miles, 0 locks, 0 moveable Hurleston Roving Bridge No 97. -

Lincolnshire County Council

APPENDIX A PARISH LOCATION TYPE PREVIOUS POSITION PRESENT POSITION 1. Anwick Chapel Lane Revocation of Prohibition of Driving Consulting 2. Bardney Horncastle Road Waiting Restrictions and Bus Stop Consulting As previous 3. Boston London Road Toucan Crossing Operative date to be arranged As previous 4. Foston Main Street Stopping Up of Highway Consulting 5. Gainsborough Beaumont Street Pedestrian Crossing Operative date to be arranged 6. Grantham Church Street / Castlegate Waiting Restrictions Consultations imminent As previous 7. Grantham Dysart Road Waiting Restrictions Consulting 8. Grantham St Catherines Road and Waiting Restrictions Operative date to be arranged As previous Welham Street Page 11 40mph Speed Limit Extension / 9. Consulting Holton le Clay A16 / Louth Road cycleway 10. Horncastle West Street / Bridge Street Waiting/Loading Restrictions Operative date to be arranged AS previous 11. Horncastle West Street Waiting Restriction Operative date to be arranged 12. Kirton Willington Road Waiting Restrictions Consulting As previous 13. Lincoln Clasketgate, Mint Street and Various Waiting Restrictions, Taxi Operative date to be arranged Operative 01/10/17 Corporation Street Rank and Loading Bay 14. Lincoln Transport Hub (St Marys Street, Waiting and Loading Restrictions Consulting Wigford Way, etc) 15. Lincoln Waterside South (Witham Park) Waiting Restrictions Operative 03/07/17 16. Lincoln Waterside South / City Sq Area Experimental Restricted Parking Operative 18/07/17 Zone 17. Mablethorpe Hammond Court Revocation of Waiting Restrictions Objections to be reviewed 18. Market Rasen Queen Street Experimental Loading Restrictions On Going Experiment As previous 19. North Witham Old Post Lane 40mph Speed Limit Consulting 1033.X0R PARISH LOCATION TYPE PREVIOUS POSITION PRESENT POSITION 20. -

Lincolnshire.. Far 683

TRADES DIRECTORY.] LINCOLNSHIRE.. FAR 683 Darnell William, Bardney, Lincoln Dawson William, Nettleton, Caistor Dickinson Thomas, Friskney, Boston Darnill George, Orby, Boston Dawson Wm. Skeldyke, Kirton, Boston DickinsonW.Sandpits,Westhorpe,Spaldg Darnill Jn. Jack, Grainthorpe, Grimsby Dawson William, Union road, Caistor Dickinson Wm. Westhorpe, Spalding Daubeny Jabez, North Kyme, Lincoln Day Edward Jas. Messingham, Brigg Dickson Frederick, Tumby, Boston Dauber John William, Ruckland, Louth Day John, Wood Enderby, Boston Diggle E. Suttun St. Edmunds, Wisbech Daubney C. Hagworthingham, Spilsby Day John Wm. Scatter, Kirton Lindsey Diggle J.H. Loosegate rd. Moultn.Spldng Dau bney Charles, Leake, Boston Day Ro bt. Scotter Hig hfield, Ki rtonLindsy DiggleJ ohnHarber, j u n. Moulton, Spaldng Daubney Charles, jun. Leake, Boston Day Robert,Scotterthorpe,KirtonLindsy Diggle Thos. Ewerby Thorpe, Sleaford Daubney George, Belchford, Horncastle Day Thomas, Church street, Caistor Diggle Thomas, Weston, Spalding Daubney H.Manor frm.Canwick, Lincoln Day William, Scatter, Kirton Lindsey Dilworth James, Horse Shoe rd.Spaldmg Daubney Henry, Wyberton, Boston Day Wm. Cotehouses, 0 wston Ferry Dimbleby W .BishopNortn. Kirtn.Lindsy Daubney James, Navenby S.O Dean Arthur W. Dowsby, Falkingham Dinnis Thomas, Anderby, Alford Daulton Austin, West Keal, Spilsby Dean Edward, Algarkirk, Boston Dinnison Thomas Hy. Burr la. Spalding Daulton Henry, Bilsby, Alford Dean John, Drayton, Swineshead,Boston Dinsdale John, Nth.Killingholme, Ulceby Daulton Jesse, The Grange, East Keal Dean John, Drove end, Wisbech Dion Frederick, Sibsey, Boston Coates, East Keal, Spilsby Dean John, Goxhill, Hull Dion James, Sibsey, Boston Daulton Joseph, Keal Coates, Spilsby Dean John Chas. Drove end, Wisbech Dion Jesse, Sibsey, Boston Daulton Thomas, East Kirkby, Spilsby Dean John Hy. -

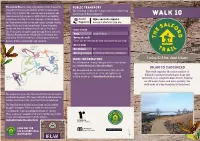

Walk 10 in Between

The Salford Trail is a new, long distance walk of about 50 public transport miles/80 kilometres and entirely within the boundaries The new way to find direct bus services to where you of the City of Salford. The route is varied, going through want to go is Route Explorer. rural areas and green spaces, with a little road walking walk 10 in between. Starting from the cityscape of Salford Quays, tfgm.com/route-explorer the Trail passes beside rivers and canals, through country Access it wherever you are. parks, fields, woods and moss lands. It uses footpaths, tracks and disused railway lines known as ‘loop lines’. Start of walk The Trail circles around to pass through Kersal, Agecroft, Walkden, Boothstown and Worsley before heading off to Train Irlam Station Chat Moss. The Trail returns to Salford Quays from the During the walk historic Barton swing bridge and aqueduct. There are no convenient drop out points on this walk Blackleach End of walk Country Park Bus Number 67 5 3 Clifton Country Park Bus stop location Lord Street Terminus, Cadishead 4 Walkden Roe Green 7 miles/11.5 km, about 4 hours Kersal more information 2 Vale 6 Worsley For information on any changes in the route please 7 Eccles go to visitsalford.info/thesalfordtrail Chat 1 Moss 8 irlam to cadishead Barton For background on the local history that you will Swing Salford This walk explores the outer reaches of 9 Bridge Quays come across on the trail or for information on Little Salford crossing reclaimed peat bogs and Woolden 10 wildlife please go to thesalfordtrail.btck.co.uk Moss farmland to go alongside Glaze Brook. -

Keep Moving! Report on the Policing of the Barton Moss Community Protection Camp, November 2013-April 2014

This is a repository copy of Keep Moving! Report on the Policing of the Barton Moss Community Protection Camp, November 2013-April 2014. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/115146/ Version: Published Version Monograph: Gilmore, Joanna orcid.org/0000-0002-4477-2825, Jackson, William and Monk, Helen (2016) Keep Moving! Report on the Policing of the Barton Moss Community Protection Camp, November 2013-April 2014. Research Report. Centre for Urban Research Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Keep Moving! REPORT ON THE POLICING OF THE BARTON MOSS COMMUNITY PROTECTION CAMP NOVEMBER 2013 - APRIL 2014 REPORT ON THE POLICING OF THE BARTON MOSS COMMUNITY CENTRE FOR THE STUDY PROTECTION CAMP OF CRIME, CRIMINALISATION NOVEMBER 2013 – APRIL 2014 AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION Written by: Dr Joanna Gilmore (York Law School, University of York), Dr Will Jackson (School of Humanities and Social Science, Liverpool John Moores University) and Dr Helen Monk (School of Humanities and Social Science, Liverpool John Moores University) All photographs by Steve Speed. -

Transactions / Lincolnshire Naturalists' Union

^, ISh LINCOLNSHIRE NATURALISTS' UNION. TRANSACTIONS, 1905-1908. VOXiXJIMIEl OIsTE. EDITED BY ARTHUR SMITH, F.L.S., F.E.S. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. Cordeaux, John Stoat without fore-limbs South Ferriby Chalk Quarry ... South Ferriby Map Burton, F. M. County Museum, Lower Story Limax maximus Fowler, Rev. Canon W. W. ... Celt and Pygmy Flints Junction of Foss Dyke and Trent Newton Cliff Fowler, Rev. Canon William ... Pre-historic Vessel at Brigg ... Early British Pottery RESUME OF THE PAST FIELD MEETINGS OF THE UNION, 1893-1905. Believing that members, who have recently joined the Union> will find some little interest in knowing where field meetings have been held in the past, and that old members will not be displeased to be reminded of what districts have been visited, this resume has been drawn up. The information contained in it will also be of some use in making future arrangements for visiting the varied surface of our wide county. On June 12th, 1893, the first Field meeting was held at MABLETHORPE — a great day for lovers of nature. Many county naturalists, and also neighbours from adjacent counties, lent their aid in making the opening day a success. The out- come was the formation of the Lincolnshire Naturalists' Union, as now constituted. The second meeting was held on August 7th, at WOOD- H.\LL SPA, and a goodly number of species were recorded. May 24th, 1894, found the members at LINCOLN. The bank of the Fossdyke and Hartsholme \^^ood were investigated, and a general meeting was held in the evening. The late John Cordeaux, M.B.O.U., was in the chair, and vacated it on the election of Mr. -

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 Edited by David M. Smith 2020 www.york.ac.uk/borthwick archbishopsregisters.york.ac.uk Online images of the Archbishops’ Registers cited in this edition can be found on the York’s Archbishops’ Registers Revealed website. The conservation, imaging and technical development work behind the digitisation project was delivered thanks to funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Register of Alexander Neville 1374-1388 Register of Thomas Arundel 1388-1396 Sede Vacante Register 1397 Register of Robert Waldby 1397 Sede Vacante Register 1398 Register of Richard Scrope 1398-1405 YORK CLERGY ORDINATIONS 1374-1399 Edited by DAVID M. SMITH 2020 CONTENTS Introduction v Ordinations held 1374-1399 vii Editorial notes xiv Abbreviations xvi York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 1 Index of Ordinands 169 Index of Religious 249 Index of Titles 259 Index of Places 275 INTRODUCTION This fifth volume of medieval clerical ordinations at York covers the years 1374 to 1399, spanning the archiepiscopates of Alexander Neville, Thomas Arundel, Robert Waldby and the earlier years of Richard Scrope, and also including sede vacante ordinations lists for 1397 and 1398, each of which latter survive in duplicate copies. There have, not unexpectedly, been considerable archival losses too, as some later vacancy inventories at York make clear: the Durham sede vacante register of Alexander Neville (1381) and accompanying visitation records; the York sede vacante register after Neville’s own translation in 1388; the register of Thomas Arundel (only the register of his vicars-general survives today), and the register of Robert Waldby (likewise only his vicar-general’s register is now extant) have all long disappeared.1 Some of these would also have included records of ordinations, now missing from the chronological sequence. -

9780521650601 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 0521650607 - Pragmatic Utopias: Ideals and Communities, 1200-1630 Edited by Rosemary Horrox and Sarah Rees Jones Index More information Index Aberdeen, Baxter,Richard, Abingdon,Edmund of,archbp of Canterbury, Bayly,Thomas, , Beauchamp,Richard,earl of Warwick, – Acthorp,Margaret of, Beaufort,Henry,bp of Winchester, adultery, –, Beaufort,Margaret,countess of Richmond, Aelred, , , , , , Aix en Provence, Beauvale Priory, Alexander III,pope, , Beckwith,William, Alexander IV,pope, Bedford,duke of, see John,duke of Bedford Alexander V,pope, beggars, –, , Allen,Robert, , Bell,John,bp of Worcester, All Souls College,Oxford, Belsham,John, , almshouses, , , , –, , –, Benedictines, , , , , –, , , , , , –, , – Americas, , Bereford,William, , anchoresses, , – Bergersh,Maud, Ancrene Riwle, Bernard,Richard, –, Ancrene Wisse, –, Bernwood Forest, Anglesey Priory, Besan¸con, Antwerp, , Beverley,Yorks, , , , apostasy, , , – Bicardike,John, appropriations, –, , , , Bildeston,Suff, , –, , Arthington,Henry, Bingham,William, – Asceles,Simon de, Black Death, , attorneys, – Blackwoode,Robert, – Augustinians, , , , , , Bohemia, Aumale,William of,earl of Yorkshire, Bonde,Thomas, , , –, Austria, , , , Boniface VIII,pope, Avignon, Botreaux,Margaret, –, , Aylmer,John,bp of London, Bradwardine,Thomas, Aymon,P`eire, , , , –, Brandesby,John, Bray,Reynold, Bainbridge,Christopher,archbp of York, Brinton,Thomas,bp of Rochester, Bristol, Balliol College,Oxford, , , , , , Brokley,John, Broomhall