Fashioning Gender Fashioning Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charitably Chic Lynn Willis

Philadelphia University Spring 2007 development of (PRODUCT) RED, a campaign significantly embraced by the fashion community. Companies working with Focus on . Alumni Focus on . Industry News (PRODUCT) RED donate a large percentage of their profits to the Global Fund to fight Lynn Willis Charitably Chic AIDS. For example, Emporio Armani’s line donates 40 percent of the gross profit By Sara Wetterlin and Chaisley Lussier By Kelsey Rose, Erin Satchell and Holly Ronan margin from its sales and the GAP donates Lynn Willis 50 percent. Additionally, American Express, Trends in fashion come and go, but graduated perhaps the first large company to join the fashions that promote important social from campaign, offers customers its RED card, causes are today’s “it” items. By working where one percent of a user’s purchases Philadelphia with charitable organizations, designers, University in goes toward funding AIDS research and companies and celebrities alike are jumping treatment. Motorola and Apple have also 1994 with on the bandwagon to help promote AIDS a Bachelor created red versions of their electronics and cancer awareness. that benefit the cause. The results from of Science In previous years, Ralph Lauren has the (PRODUCT) RED campaign have been in Fashion offered his time and millions of dollars to significant, with contributions totaling over Design. Willis breast cancer research and treatment, which $1.25 million in May 2006. is senior includes the establishment of health centers Despite the fashion industry’s focus on director for the disease. Now, Lauren has taken image, think about what you can do for of public his philanthropy further by lending his someone else when purchasing clothes relations Polo logo to the breast cancer cause with and other items. -

Source Issue 2

SS | 2015 LISTEN LIVE HACKNEY MUSIC HANG-OUTS MEET THE MAKERS LONDON INNOVATION AT ITS BEST FRESH LONDON LIVING IN AND AROUND WOODBERRY DOWN WOODBERRY AROUND LIVING IN AND FRESH LONDON HACKNEY CYCLE GUIDE TEAR OUT AND SADDLE UP HAND CRAFTED THE ART OF THE MICROBREWERY discover the river AT your doorstep... FREE new Welcome elcome to the Spring In the midst of one of the capital’s most river Summer 2015 issue of eclectic areas, Woodberry Down is a Source magazine. place that offers the tranquility of nature alongside a rich sense of community. As the season invites the TRAIL W Steeped in history, the area promises an opportunity for adventure, we curate the exciting future as it undergoes substantial very best North London experiences to fill growth. those long summer days and balmy nights. Source is published on behalf of Berkeley, From exploring the nature trail at 3rd october 2015 one of the UK’s most respected residential Woodberry Wetlands to the local summer developers and recipient of The Queen’s market, outdoor cinema screenings Award for Enterprise. As a company that and the popular Hidden River Festival, builds not just homes but helps create nowhere else in London offers such a neighbourhoods, Source is designed to varied place to live. celebrate the people and places that shape Food STALLS a genuinely vibrant community. Through a mix of interviews, reviews and feature articles, discover an area known for HISTORY innovation, craftsmanship, arts and culture. SAVE the reservoirs CAMPAIGn live music THEATRE Source on your tablet Available on your iPad or NATURE CELEBRATION Android tablet. -

Impact Investing in the Creative Economy: Diving Deep Into Ethical Fashion, Sustainable Food and Social Impact Media

Impact Investing in the Creative Economy: diving deep into Ethical Fashion, Sustainable Food and Social Impact Media Creatve people solve problems. Increasingly, In an efort to demystfy the creatve economy they are doing it beyond the studio, the for impact investors, impact fund managers and theater and the concert hall. Creatve people other stakeholders, this report dives deep into are harnessing the power of business and the three large and growing consumer industries marketplace to scale and sustain their ideas. within the creatve economy: fashion, food and media. These industries share the capacity to Many of the businesses that artsts, designers intrigue, engage, educate and actvate more and other creatves start balance fnancial mindful consumers so that the benefts of proftability with concern for the planet, ethical and sustainable supply chains and the their workers, and their community. These full power of media to drive positve change can socially-focused companies seek capital from be realized. impact investors who understand the power of art, design, culture, heritage and creatvity to Creatve Economy Defned drive positve environmental and social impact. Together, investors and entrepreneurs can The “creatve economy” was defned by John grow the creatve economy to become more Howkins in 2001 as a new way of thinking and inclusive, equitable and sustainable. doing that revitalizes manufacturing, services, retailing, and entertainment industries with A Creatvity Lens: Impact Investng in the Creatve Economy 1 a focus on individual talent or skill, and art, The Opportunity culture, design, and innovaton. Concern by consumers about how their food, Today, creatve economy defnitons are clothes and entertainment are produced has typically ted to eforts to measure economic grown signifcantly in recent years. -

Grin and Bear It

AMERICAN ANTHEM MADE IN THE USA IS SEEING A RESURGENCE AND IT’S A KEY POLITICAL ISSUE. SECTION II MALE MAKEOVER BERGDORF GOODMAN UNVEILS A REMODELED MEN’S DEPARTMENT. PAGE 3 LUXURY LAWSUITS Hermès Sues LVMH, LVMH Sues Hermès By JOELLE DIDERICH PARIS — Let the hostilities resume. Hermès International and LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton said Tuesday they were heading to court over their ongoing dispute regarding LVMH’s WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2012 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR D acquisition of a 22.3 percent stake in the maker of Birkin bags and silk scarves. WWD Hermès confi rmed that on July 10, it lodged a com- plaint with a Paris court against LVMH, which sur- prised markets by revealing in October 2010 that it had amassed a 17.1 percent stake in Hermès via cash- settled equity swaps that allowed it to circumvent the usual market rules requiring fi rms to declare share Grin and purchases. The world’s biggest luxury group has since steadily increased its stake, a move seen by Hermès offi cials as an attempt at a creeping takeover, despite reassur- Bear It ances from LVMH chairman and chief executive offi - cer Bernard Arnault that he is not seeking full control. With more than 50 “This complaint concerns the terms of LVMH’s ac- quisition of stock in Hermès International,” Hermès collections under her low- said in a two-line statement. It is accusing LVMH of slung belt, Donna Karan, insider trading, collusion and manipulating stock shown here in her studio, prices, according to a source familiar with the issue, who declined to be named for confi dentiality reasons. -

Cathy Henszey Creative Director = Innovation + Marketer + Graphic Design + Manager + Talent Scout + Mentor

Cathy Henszey Creative Director = innovation + marketer + graphic design + manager + talent scout + mentor Visionary designer with an impressive portfolio and record of driving business for diverse 347 886 2061 industries. Passion for creating sharp, professional, and unique designs that immediately attract clients. Skilled in developing high impact brand identities, advertising, marketing materials, web sites, and social media campaigns. Track record of meeting demanding www.cathyhenszey.com deadlines, communicating effectively, with multiple cross-functional teams, and leading [email protected] by example. Dedicated to finding the most cost-effective and creative solutions for all challenges. Known for taking a hands on approach in directing artists, collaborating with clients, and bringing creative concepts to life. Core Competencies Company Branding + Identity Development + Image Building + Client Service and management + Print Materials + Graphic Design + Marketing and Advertising + Communication Campaigns + Social Media Campaigns + Collateral Materials + Web Site Design + Packaging Design + Product Development + Event Design + Posters & Signs + Trend Forecasting + Retail Fixtures and Displays + Apparel Graphics and Trim Design + TV and Video + Conceptual Direction + Lay out and compositions + Font and Color Management + Staff Inspiration & Training + Project Management + Hiring and Recruiting + Typography + Budget Man- agement and Scheduling Recent Consulting and Design Projects 2012-2013 Sherle Wagner - Promotional designs for -

Fashion Awards Preview

WWD A SUPPLEMENT TO WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY 2011 CFDA FASHION AWARDS PREVIEW 053111.CFDA.001.Cover.a;4.indd 1 5/23/11 12:47 PM marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG WWD Published by Fairchild Fashion Group, a division of Advance Magazine Publishers Inc., 750 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 EDITOR IN CHIEF ADVERTISING Edward Nardoza ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, Melissa Mattiace ADVERTISING DIRECTOR, Pamela Firestone EXECUTIVE EDITOR, BEAUTY Pete Born PUBLISHER, BEAUTY INC, Alison Adler Matz EXECUTIVE EDITOR Bridget Foley SALES DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR, Jennifer Marder EDITOR James Fallon ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, INNERWEAR/LEGWEAR/TEXTILE, Joel Fertel MANAGING EDITOR Peter Sadera EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL FASHION, Matt Rice MANAGING EDITOR, FASHION/SPECIAL REPORTS Dianne M. -

Press Release 15 January 2013 Swarovski Whitechapel Gallery Art

Press Release 15 January 2013 Swarovski Whitechapel Gallery Art Plus Fashion: Giles Deacon , Bella Freud, Marios Schwab and Nadja Swarovski collaborate with the Whitechapel Gallery for annual fundraising gala 14 March 2013, 7pm - late The Whitechapel Gallery announces an exceptional evening of art, fashion and moving-image on Thursday 14 March 2013 for the annual fundraising gala in partnership with Swarovski. Major names from the world of fashion including Giles Deacon , Bella Freud, Marios Schwab and Nadja Swarovski select the most promising fashion postgraduates emerging from London to take centre stage in the first ever live catwalk show in the Gallery. Whitechapel Gallery Director Iwona Blazwick OBE , Nadja Swarovski , Member of Swarovski’s Executive Board, Mollie Dent-Brocklehurst , Art Plus Chair and Justine Picardie , Harper’s Bazaar Editor-in-Chief, lead a committee of renowned figures from the worlds of art, fashion, film and music, inviting guests to join an evening premiering the next generation of designers. Funds raised support the Whitechapel Gallery’s Education programme, which works with thousands of children and diverse community groups every year. For Swarovski Whitechapel Gallery Art Plus Fashion , outstanding postgraduate fashion collections will be paired with work by leading moving-image artists, followed by live music and celebrity DJs. An auction led by Sotheby’s Oliver Barker includes works generously donated by major contemporary artists. Guests will have the opportunity to bid on works by Andrea Büttner , Minerva Cuevas, Corinne Day, Sam Durant, Cornelia Parker, Bridget Riley, Bob and Roberta Smith and Catherine Yass . Swarovski Whitechapel Gallery Art Plus Fashion will feature a stunning catwalk show with creative direction by Sara Blonstein and Chris Ford from Blonstein & Associates . -

Stephen Jones Datasheet

TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +44 (0) 1394 389950 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/uk Stephen Jones And the Accent of Fashion Hanish Bowles ISBN 9781851496525 Publisher ACC Art Books Binding Hardback Territory World Size 300 mm x 240 mm Pages 240 Pages Illustrations 297 color Price £45.00 First monograph on the work of the celebrated milliner Stephen Jones With a preface by John Galliano and texts by authorities such as Hamish Bowles, Andrew Bolton, Suzy Menkes and Anna Piaggi, with new photography by Nick Knight and David Bailey "Picture the moment, in the run-up to a Christian Dior haute couture show. John Galliano is working silently in the Paris studio with his friend and ally, the master milliner Stephen Jones. The designer is looking at the arc of a silhouette, the drape of a skirt and the tilt of a hat: 'I often work through a mirror for most of my decisions and I always see Stephen's reflection,' says Galliano. 'He is reading my every nuance. He is studying my face. I don't need to say anything - he can read my mind'." - From the essay by Suzy Menkes. Stephen Jones is one of the world's most talented and distinguished milliners. This exquisitely illustrated monograph is the first to examine his illustrious career and famous collaborations. Including photographs from private collections and museums, the book focuses on a variety of aspects of his work, from his collaborations with Boy George, John Galliano and Thierry Mugler to his work with photographers Bruce Weber and Nick Knight. -

The Aesthetics of Mainstream Androgyny

The Aesthetics of Mainstream Androgyny: A Feminist Analysis of a Fashion Trend Rosa Crepax Goldsmiths, University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Sociology May 2016 1 I confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Rosa Crepax Acknowledgements I would like to thank Bev Skeggs for making me fall in love with sociology as an undergraduate student, for supervising my MA dissertation and encouraging me to pursue a PhD. For her illuminating guidance over the years, her infectious enthusiasm and the constant inspiration. Beckie Coleman for her ongoing intellectual and moral support, all the suggestions, advice and the many invaluable insights. Nirmal Puwar, my upgrade examiner, for the helpful feedback. All the women who participated in my fieldwork for their time, patience and interest. Francesca Mazzucchi for joining me during my fieldwork and helping me shape my methodology. Silvia Pezzati for always providing me with sunshine. Laura Martinelli for always being there when I needed, and Martina Galli, Laura Satta and Miriam Barbato for their friendship, despite the distance. My family, and, in particular, my mum for the support and the unpaid editorial services. And finally, Goldsmiths and everyone I met there for creating an engaging and stimulating environment. Thank you. Abstract Since 2010, androgyny has entered the mainstream to become one of the most widespread trends in Western fashion. Contemporary androgynous fashion is generally regarded as giving a new positive visibility to alternative identities, and signalling their wider acceptance. But what is its significance for our understanding of gender relations and living configurations of gender and sexuality? And how does it affect ordinary people's relationship with style in everyday life? Combining feminist theory and an aesthetics that contrasts Kantian notions of beauty to bridge matters of ideology and affect, my research investigates the sociological implications of this phenomenon. -

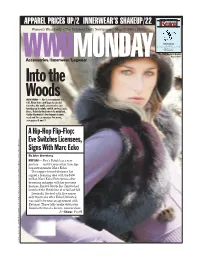

Into the Woods NEW YORK — Fur Is Everywhere for Fall

APPAREL PRICES UP/2 INNERWEAR’S SHAKEUP/22 THETHE WWD BUSINESS REVIEW THE RETAILERS’ DAILY NEWSPAPER MAY 17, 2004 Women’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • May 17, 2004 • $2.00 STAYING AFLOAT Bailing or Smooth Sailing? Fashion Retail on an Uncertain Voyage. From the impact of a jobless recovery to curbed consumer spending in a post-refinancing boom era, retail faces daunting seas. {But the tide could change as the industry is buoyed by a consumer demographic that can’t seem to get enough of luxury goods. } Nouveau Riche II: ‘Masstige’ Cash Machine: Refinancing Over? Factors on China: Trade 2005 ▲ The WWD Business Review. WWDMONDAY Pages 9-20. Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear Into the Woods NEW YORK — Fur is everywhere for fall. From hats and bags to an old favorite, the muff, accessories are turning up in mink, rabbit and raccoon. Here, Patricia Underwood’s mink hat, Cathy Hardwick’s fox-trimmed mink vest and Tocca sweater. For more, see pages 6 and 7. A Hip-Hop Flip-Flop: Eve Switches Licensees, Signs With Marc Ecko By Julee Greenberg ED BY ROXANNE ROBINSON-ESCRIOUT ED BY NEW YORK — Eve’s Fetish has a new partner — and it’s none other than hip- hop entrepreneur Marc Ecko. The rapper-turned-designer has signed a licensing deal with the $350 million Marc Ecko Enterprises after OS, BOTH AT WARREN TRICOMI; STYL WARREN OS, BOTH AT becoming unhappy with her previous licensee, Innovo Group Inc. Innovo had launched the Fetish line at retail last fall. Ironically, the deal with Eve comes only two weeks after Ecko Unlimited Y ROANNA, HAIR BY DENNIS GOTOUL Y ROANNA, HAIR BY was said to be near an agreement with Beyoncé. -

Yeshiva University

FASHION (Selection of organizations) Listed below are a few organizations to help you get started in your search. The CDC compiled this list through both research and previous job postings with our office. Always do your research first and keep in mind that organizations receive numerous requests for internships/jobs. Be professional at all times and only contact companies in which you have a serious interest. This handout is by no means an all inclusive list. It is meant solely as a tool to introduce you to some of the organizations in your field of interest. Executive Training and Buying (Full-time) Abercrombie & Fitch Jones Group Adjmi Apparel Loehmann’s Aerpostale MACY’S East American Eagle Outfitters Michael Kors Ann Taylor Nautica Associated Merchandising Corp. Newport News A/X Armani Exchange Old Navy Gap, Inc. Perry Ellis Barney’s Polo Ralph Lauren Bergdorf Goodman Polo Jeans Bloomingdales Prada Brooks Brothers Saks Fifth Avenue Calvin Klein, Inc. Steve Madden Coach The Children’s Place Macy’s Merchandising Group Tiffany & Co., GFT USA Corp Tommy Hilfiger Guess Warnaco, Inc. Home Bed Bath & Beyond Gracious Home Crate & Barrel Restoration Hardware Fragrances/Cosmetics AVON International Flavor & Fragrances Chanel Inc. Lancome LLC Clarins USA Inc L’Oreal USA COTY Inc. Maybelline Elizabeth Arden Revlon, Inc. Estee Lauder Co., Executive Training and Buying (Internship) Agent 011 Limited Brands (The Limited Stores) Alper International Liz Claiborne Anthropologie MACY’S Ariela-Alpha Maurice Malone: MoeMos: MoeJeans A/X --Armani Exchange Norma Kamali Betsy Johnson norma kamali-Barxv Wellness Calvin Klein Patricia Underwood Christian Dior Couture Phillips Van Heusen: CJ Apparel Group LLC Planet Sox Coach Polo Ralph Lauren Cocomo Connection Prairie NY Cynthia Rose New York Rachel Reinhardt Donna Karan NY Rebecca Romero Eli Tahari Saks Fifth Avenue Elizabeth Gillett NYC Select Showroom Escada USA Inc. -

As Former Creative Director at Yves Saint Laurent, Stefano Pilati Is

35 FASHION STEFANO PILATI As former creative director at Yves Saint RANDOM IDENTITIES Laurent, Stefano Pilati is fnally lying low, YVES SAINT LAURENT and loving it. “My experience gave me a lot, but it also took a lot away from me,” he says. “And that’s why I’m excited now. I don’t need those flters anymore.” Pilati’s passion for fashion design is undeniable, and he relishes the labor that goes into it. “When you work for a big company, you have less and less time to do your job efectively,” he explains. “Now I fnd myself doing more within the day-to-day design process.” Pilati exudes enthusiasm while discussing his current project, Random Identities, which he describes as “a combina- tion of technical advancements for a new and personal way to approach fashion.” Pilati is revered not only for his designs (like the highly sensational tulip skirt) but also for his unconventional yet elegant personal style. “People who don’t know me think that my style is a big efort, but it’s not an efort at all,” he muses. It is, he adds, always evolving based on his environment. His home and ofce ← share the same space, the two upper foors of Though he no longer lives in his hometown, Pilati a historical building in Berlin. (Pilati notes thinks fondly of the city. that the adjacency of his studio and living “Milan is beautiful,” he space is a conscious choice. “It allows me to says. “I recognize myself in its architecture, in isolate myself in my own creativity,” he says.) its colors.” Having moved to the German capital several The_Eye_FINAL_PASS_6-6.indd 34-35 6/11/18 5:10 PM The_Eye_FINAL_PASS_6-6.indd 36-37 6/11/18 5:10 PM 38 THE EYE → Pilati met Yves Saint Laurent only once, but treasures the letters he sent, signed with the word “amitié” (“friendship”).