Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charitably Chic Lynn Willis

Philadelphia University Spring 2007 development of (PRODUCT) RED, a campaign significantly embraced by the fashion community. Companies working with Focus on . Alumni Focus on . Industry News (PRODUCT) RED donate a large percentage of their profits to the Global Fund to fight Lynn Willis Charitably Chic AIDS. For example, Emporio Armani’s line donates 40 percent of the gross profit By Sara Wetterlin and Chaisley Lussier By Kelsey Rose, Erin Satchell and Holly Ronan margin from its sales and the GAP donates Lynn Willis 50 percent. Additionally, American Express, Trends in fashion come and go, but graduated perhaps the first large company to join the fashions that promote important social from campaign, offers customers its RED card, causes are today’s “it” items. By working where one percent of a user’s purchases Philadelphia with charitable organizations, designers, University in goes toward funding AIDS research and companies and celebrities alike are jumping treatment. Motorola and Apple have also 1994 with on the bandwagon to help promote AIDS a Bachelor created red versions of their electronics and cancer awareness. that benefit the cause. The results from of Science In previous years, Ralph Lauren has the (PRODUCT) RED campaign have been in Fashion offered his time and millions of dollars to significant, with contributions totaling over Design. Willis breast cancer research and treatment, which $1.25 million in May 2006. is senior includes the establishment of health centers Despite the fashion industry’s focus on director for the disease. Now, Lauren has taken image, think about what you can do for of public his philanthropy further by lending his someone else when purchasing clothes relations Polo logo to the breast cancer cause with and other items. -

Clothing of Kansas Women, 1854-1870

CLOTHING OF KANSAS WOMEN 1854 - 1870 by BARBARA M. FARGO B. A., Washburn University, 1956 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Clothing, Textiles and Interior Design KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1969 )ved by Major Professor ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express sincere appreciation to her adviser, Dr. Jessie A. Warden, for her assistance and guidance during the writing of this thesis. Grateful acknowledgment also is expressed to Dr. Dorothy Harrison and Mrs. Helen Brockman, members of the thesis committee. The author is indebted to the staff of the Kansas State Historical Society for their assistance. TABLE OP CONTENTS PAGE ACKNOWLEDGMENT ii INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURE 1 REVIEW OF LITERATURE 3 CLOTHING OF KANSAS WOMEN 1854 - 1870 12 Wardrobe planning 17 Fabric used and produced in the pioneer homes 18 Style and fashion 21 Full petticoats 22 Bonnets 25 Innovations in acquisition of clothing 31 Laundry procedures 35 Overcoming obstacles to fashion 40 Fashions from 1856 44 Clothing for special occasions 59 Bridal clothes 66 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 72 REFERENCES 74 LIST OF PLATES PLATE PAGE 1. Bloomer dress 15 2. Pioneer woman and child's dress 24 3. Slat bonnet 30 4. Interior of a sod house 33 5. Children's clothing 37 6. A fashionable dress of 1858 42 7. Typical dress of the 1860's 47 8. Black silk dress 50 9. Cape and bonnet worn during the 1860's 53 10. Shawls 55 11. Interior of a home of the late 1860's 58 12. -

Impact Investing in the Creative Economy: Diving Deep Into Ethical Fashion, Sustainable Food and Social Impact Media

Impact Investing in the Creative Economy: diving deep into Ethical Fashion, Sustainable Food and Social Impact Media Creatve people solve problems. Increasingly, In an efort to demystfy the creatve economy they are doing it beyond the studio, the for impact investors, impact fund managers and theater and the concert hall. Creatve people other stakeholders, this report dives deep into are harnessing the power of business and the three large and growing consumer industries marketplace to scale and sustain their ideas. within the creatve economy: fashion, food and media. These industries share the capacity to Many of the businesses that artsts, designers intrigue, engage, educate and actvate more and other creatves start balance fnancial mindful consumers so that the benefts of proftability with concern for the planet, ethical and sustainable supply chains and the their workers, and their community. These full power of media to drive positve change can socially-focused companies seek capital from be realized. impact investors who understand the power of art, design, culture, heritage and creatvity to Creatve Economy Defned drive positve environmental and social impact. Together, investors and entrepreneurs can The “creatve economy” was defned by John grow the creatve economy to become more Howkins in 2001 as a new way of thinking and inclusive, equitable and sustainable. doing that revitalizes manufacturing, services, retailing, and entertainment industries with A Creatvity Lens: Impact Investng in the Creatve Economy 1 a focus on individual talent or skill, and art, The Opportunity culture, design, and innovaton. Concern by consumers about how their food, Today, creatve economy defnitons are clothes and entertainment are produced has typically ted to eforts to measure economic grown signifcantly in recent years. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Swagger Like Us: Black Millennials' Perceptions of 1990S Urban Brands

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2018 Swagger like us: Black millennials’ perceptions of 1990s urban brands Courtney Danielle Johnson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the American Material Culture Commons, and the Fashion Design Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Courtney Danielle, "Swagger like us: Black millennials’ perceptions of 1990s urban brands" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 16600. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/16600 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Swagger like us: Black millennials’ perceptions of 1990s urban brands by Courtney Danielle Johnson A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Apparel, Merchandising and Design Program of study committee: Eulanda A. Sanders, Co-major Professor Kelly L. Reddy-Best, Co-major Professor Tera Jordan The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2018 Copyright © Courtney Danielle Johnson, 2018. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Black folks. -

Fashioning Gender Fashioning Gender

FASHIONING GENDER FASHIONING GENDER: A CASE STUDY OF THE FASHION INDUSTRY BY ALLYSON STOKES, B.A.(H), M.A. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES OF MCMASTER UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY c Copyright by Allyson Stokes, August 2013 All Rights Reserved Doctor of Philosophy (2013) McMaster University (Sociology) Hamilton, Ontario, Canada TITLE: Fashioning Gender: A Case Study of the Fashion Industry AUTHOR: Allyson Stokes BA.H., MA SUPERVISOR: Dr. Tina Fetner NUMBER OF PAGES: xii, 169 ii For Johnny. iii Abstract This dissertation uses the case of the fashion industry to explore gender inequality in cre- ative cultural work. Data come from 63 in-depth interviews, media texts, labor market statistics, and observation at Toronto’s fashion week. The three articles comprising this sandwich thesis address: (1) processes through which femininity and feminized labor are devalued; (2) the gendered distribution of symbolic capital among fashion designers; and (3) the gendered organization of the fashion industry and the “ideal creative worker.” In chapter two, I apply devaluation theory to the fashion industry in Canada. This chap- ter makes two contributions to literature on the devaluation of femininity and “women’s work.” First, while devaluation is typically used to explain the gender wage gap, I also address symbolic aspects of devaluation related to respect, prestige, and interpretations of worth. Second, this paper shows that processes of devaluation vary and are heavily shaped by the context in which work is performed. I address five processes of devaluation in fash- ion: (1) trivialization, (2) the privileging of men and masculinity, (3) the production of a smokescreen of glamour, (4) the use of free labor and “free stuff,” and (5) the construction of symbolic boundaries between “work horses” and “show ponies.” In chapter three, I use media analysis to investigate male advantage in the predomi- nantly female field of fashion design. -

Unlocking the Reuse Revolution for Fashion: a Canadian Case Study

Unlocking the Reuse Revolution for Fashion: A Canadian Case Study by Laura Robbins Submitted to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Design in Strategic Foresight & Innovation Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2019 Copyright Notice This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/4.0/ You are free to: • Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material Under the following conditions: • Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. • NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. • ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. ii ABSTRACT This research aims to explore the potential of clothing reuse as a stepping stone towards a more circular economy for fashion. A systems approach to problem finding, framing, and solving is applied to explore how we might increase fashion reuse behaviours amongst consumers and industry alike. This research includes an analysis of the key barriers that prevent higher rates of participation in fashion reuse despite the potential economic, environmental, and social benefits of doing so (Part 2), and identifies areas of opportunity to focus innovation (Part 3). Research methodology included more than 30 one-on-one consumer interviews, 20 interviews with industry professionals along the fashion value chain, and an extensive environmental scan with a particular focus on the Canadian market. -

Final Thesis

AN EXAMINATION OF INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ITALIAN AND AMERICAN FASHION CULTURES: PAST, PRESENT, AND PROJECTIONS FOR THE FUTURE BY: MARY LOUISE HOTZE TC 660H PLAN II HONORS PROGRAM THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN MAY 10, 2018 ______________________________ JESSICA CIARLA DEPARTMENT OF TEXTILES AND APPAREL SUPERVISING PROFESSOR ______________________________ ANTONELLA DEL FATTORE-OLSON DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH AND ITALIAN SECOND READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………….…………………………………………….…………………………………… 3 Acknowledgements………………………………………….…………………………………………….…………..……….. 4 Introduction………………………………………….…………………………………………….…………………….…….…. 5 Part 1: History of Italian Fashion……...……...……..……...……...……...……...……...……...……...... 9 – 47 AnCiEnt Rome and thE HoLy Roman EmpirE…………………………………………………….……….…... 9 ThE MiddLE AgEs………………………………………….……………………………………………………….…….. 17 ThE REnaissanCE……………………………………….……………………………………………………………...… 24 NeoCLassism to RomantiCism……………………………………….…………………………………….……….. 32 FasCist to REpubLiCan Italy……………………………………….…………………………………….……………. 37 Part 2: History of American Fashion…………………………………………….……………………………… 48 – 76 ThE ColoniaL PEriod……………………………………….……………………………………………………………. 48 ThE IndustriaL PEriod……………………………………….……………………………………………………….…. 52 ThE CiviL War and Post-War PEriod……………………………………….……………………………………. 58 ThE EarLy 20th Century……………………………………….………………………………………………….……. 63 ThE Mid 20th Century……………………………………….…………………………………………………………. 67 ThE LatE 20th Century……………………………………….………………………………………………………… 72 Part 3: Discussion of Individual -

School of Fashion Program Brochure

School of Fashion academyart.edu SCHOOL OF FASHION Contents Program Overview ...................................................5 What We Teach ......................................................... 7 Faculty .....................................................................11 Degree Options ..................................................... 15 Our Facilities ........................................................... 17 Student & Alumni Testimonials ........................... 19 Partnerships ......................................................... 23 Career Paths ......................................................... 25 Additional Learning Experiences ......................... 27 Awards and Accolades ......................................... 29 Online Education ................................................... 31 Academy Life ........................................................ 33 San Francisco ....................................................... 35 Athletics ................................................................ 37 Apply Today .......................................................... 39 3 SCHOOL OF FASHION Program Overview As a student at Academy of Art’s School of Fashion, you can go after the fashion career of your dreams. Aspiring designer? Learn to turn your fashion concepts into relevant, responsible, and beautiful work. More interested in the business of fashion? Future entrepreneurs thrive in our fashion-specific business and communications programs. FIND YOUR PLACE WHAT SETS US APART Academy -

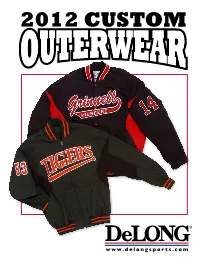

DOW 300 Matching Sleeves

www.delongsports.com DOW 300 matching sleeves Adult* 20 - Oxford Nylon 25 - Flight Satin 29 - Poly/Dobby NEW 40 - Cordura Taslan 45 - Poly/Ultra Soft NEW *To order Youth, add a Y at the end of the style number. • Available in outerwear AR fabric options above E • Set-in sleeves match body • Matching or contrasting Insert/lower sleeve • Snap front closure RW standard • Zipper front closure optional, EXTRA • All optional collars available, EXTRA (7, 4, S, UTE N/C) • Collars S, K and W O require Zipper front, EXTRA • Knit 7, 8, K and W collars may contrast with the cuffs and band • Two front welt pockets • All optional linings available, EXTRA. • SIZES: Adult XS-6XL Youth S-XL Note: Regular size is standard. "long" (2" longer in the body and 1" longer in sleeve length) and available at 10% EXTRA "Extra Long" (4" longer in body 2" longer in sleeve.) are available at 20% EXTRA Fabric New Fabric Importance 29 - 100% Polyester high • Breathability in diverse count Dobby with DWR conditions finish, 2A wash test and a • Wind Resistant water resistant breathable • Low water absorption coating. • Water repellency (DWR) New Fabric • Retains durability after 45 - 94% Polyester/ 6% washings (2A Wash) Spandex Ultra Soft face • Color Consistency- with a 4 way stretch. 100% Finishing Process polyester laminated fleece 2012 DELONG CUSTOM 2012 DELONG CUSTOM backing with anti-pilling. DWR finish with 2A wash Teflon/Breathable coating. This all-purpose fabric can be worn year round and with its moisture management characteristic, makes it incredibly durable. page 2 877.820.0916 | fax 800.998.1904 DOW 031 set-in sleeves Adult* • Set-in sleeves match • Knit 7, 8, K and W 20 - Oxford Nylon body or contrast body collars may contrast 25 - Flight Satin • Snap front closure with the cuffs and band 29 - Poly/Dobby NEW standard • Two front welt pockets 40 - Cordura Taslan • Zipper front closure • All optional linings 45 - Poly/Ultra Soft 2012 DELONG CUSTOM NEW optional, EXTRA available, EXTRA. -

Locational Relationality in Hedi Slimane and Helmut Lang Susan Ingram

Document généré le 3 oct. 2021 03:30 Imaginations Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies Revue d’études interculturelles de l’image Where the Boys Who Keep Swinging Are Now Locational Relationality in Hedi Slimane and Helmut Lang Susan Ingram Fashion Cultures and Media – Canadian Perspectives Résumé de l'article Cultures et médias de la mode – Perspectives canadiennes Cet article illustre les mécanismes par lesquels Berlin et Vienne en sont venus à Volume 9, numéro 2, 2018 figurer différemment dans l’imaginaire mondial de la mode. Il établit la relation locale stylistique de Hedi Slimane et Helmut Lang, deux dessinateurs URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1059167ar de mode connus pour leur styles distictintifs qui résistent aux normes DOI : https://doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.FCM.9.2.7 prévalentes de la respectabilité bourgeoise. La nature relationnelle de leurs identités géographiques—L’attrait de Berlin pour Slimane et le rejet de Vienne pour Lang—est liée à l’imaginaire urbain des deux villes, ce qui se manifeste en Aller au sommaire du numéro rendant hégémoniques des aspects particuliers des époques et du style de l’histoire des deux villes. Éditeur(s) York University ISSN 1918-8439 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Ingram, S. (2018). Where the Boys Who Keep Swinging Are Now: Locational Relationality in Hedi Slimane and Helmut Lang. Imaginations, 9(2), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.FCM.9.2.7 All Rights Reserved ©, 2018 Susan Ingram Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Tragédie Nipponne / Norwegian Wood D'anh Hung Tran, Japon, 2010

Document generated on 09/25/2021 12:17 a.m. Ciné-Bulles Tragédie nipponne Norwegian Wood d’Anh Hung Tran, Japon, 2010, 133 min Luc Laporte-Rainville Volume 29, Number 3, Summer 2011 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/64543ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec ISSN 0820-8921 (print) 1923-3221 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Laporte-Rainville, L. (2011). Review of [Tragédie nipponne / Norwegian Wood d’Anh Hung Tran, Japon, 2010, 133 min]. Ciné-Bulles, 29(3), 59–59. Tous droits réservés © Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ tement l’Andromaque de Racine dès la sixième minute du film. L’amour à sens uni- que est l’idée maîtresse de cette pièce de théâtre. Andromaque, fidèle à son mari Hector décédé durant la guerre de Troie, CRITIQUES refuse de se donner à Pyrrhus. Et ce motif tragique est repris sans détour par le ci- néaste. Car telle une Andromaque moder- ne, Naoko ne peut faire don d’un amour en- tier à Toru, la sensation d’être infidèle à Kizuki étant trop forte.