Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Bibiical Drama by Chester N. Scoville a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with The

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English BibIical Drama by Chester N. Scoville A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto O Copyright by Chester N. Scoville (2000) National Library Bibiiotheque nationale l*l ,,na& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rwW~gtm OttawaON KlAûîU4 OtÈewaûN K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otheMrise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract of Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2000 Department of English, University of Toronto The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Biblical Dnma by Chester N. Scovilie Much past criticism of character in Middle English drarna has fallen into one of two rougtily defined positions: either that early drama was to be valued as an example of burgeoning realism as dernonstrated by its villains and rascals, or that it was didactic and stylized, meant primarily to teach doctrine to the faithfùl. -

Business Professional Dress Code

Business Professional Dress Code The way you dress can play a big role in your professional career. Part of the culture of a company is the dress code of its employees. Some companies prefer a business casual approach, while other companies require a business professional dress code. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR MEN Men should wear business suits if possible; however, blazers can be worn with dress slacks or nice khaki pants. Wearing a tie is a requirement for men in a business professional dress code. Sweaters worn with a shirt and tie are an option as well. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR WOMEN Women should wear business suits or skirt-and-blouse combinations. Women adhering to the business professional dress code can wear slacks, shirts and other formal combinations. Women dressing for a business professional dress code should try to be conservative. Revealing clothing should be avoided, and body art should be covered. Jewelry should be conservative and tasteful. COLORS AND FOOTWEAR When choosing color schemes for your business professional wardrobe, it's advisable to stay conservative. Wear "power" colors such as black, navy, dark gray and earth tones. Avoid bright colors that attract attention. Men should wear dark‐colored dress shoes. Women can wear heels or flats. Women should avoid open‐toe shoes and strapless shoes that expose the heel of the foot. GOOD HYGIENE Always practice good hygiene. For men adhering to a business professional dress code, this means good grooming habits. Facial hair should be either shaved off or well groomed. Clothing should be neat and always pressed. -

Tartan As a Popular Commodity, C.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), Pp

Tuckett, S. (2016) Reassessing the romance: tartan as a popular commodity, c.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), pp. 182-202. (doi:10.3366/shr.2016.0295) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/112412/ Deposited on: 22 September 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk SALLY TUCKETT Reassessing the Romance: Tartan as a Popular Commodity, c.1770-1830 ABSTRACT Through examining the surviving records of tartan manufacturers, William Wilson & Son of Bannockburn, this article looks at the production and use of tartan in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While it does not deny the importance of the various meanings and interpretations attached to tartan since the mid-eighteenth century, this article contends that more practical reasons for tartan’s popularity—primarily its functional and aesthetic qualities—merit greater attention. Along with evidence from contemporary newspapers and fashion manuals, this article focuses on evidence from the production and popular consumption of tartan at the turn of the nineteenth century, including its incorporation into fashionable dress and its use beyond the social elite. This article seeks to demonstrate the contemporary understanding of tartan as an attractive and useful commodity. Since the mid-eighteenth century tartan has been subjected to many varied and often confusing interpretations: it has been used as a symbol of loyalty and rebellion, as representing a fading Highland culture and heritage, as a visual reminder of the might of the British Empire, as a marker of social status, and even as a means of highlighting racial difference. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes

1914 Girl's Afternoon Dress Pattern Notes: I created this pattern as a companion for my women’s 1914 Afternoon Dress pattern. At right is an illustration from the 1914 Home Pattern Company catalogue. This is, essentially, what this pattern looks like if you make it up with an overskirt and cap sleeves. To get this exact look, you’d embroider the overskirt (or use eyelet), add a ruffle around the neckline and put cuffs on the straight sleeves. But the possibilities are as limitless as your imagination! Styles for little girls in 1914 had changed very little from the early Edwardian era—they just “relaxed” a bit. Sleeves and skirt styles varied somewhat over the years, but the basic silhouette remained the same. In the appendix of the print pattern, I give you several examples from clothing and pattern catalogues from 1902-1912 to show you how easy it is to take this basic pattern and modify it slightly for different years. Skirt length during the early 1900s was generally right at or just below the knee. If you make a deep hem on this pattern, that is where the skirt will hit. However, I prefer longer skirts and so made the pattern pieces long enough that the skirt will hit at mid-calf if you make a narrow hem. Of course, I always recommend that you measure the individual child for hem length. Not every child will fit exactly into one “standard” set of pattern measurements, as you’ll read below! Before you begin, please read all of the instructions. -

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815 Mark Wishon Ph.D. Thesis, 2011 Department of History University College London Gower Street London 1 I, Mark Wishon confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Throughout the ‘long eighteenth century’ Britain was heavily reliant upon soldiers from states within the Holy Roman Empire to augment British forces during times of war, especially in the repeated conflicts with Bourbon, Revolutionary, and Napoleonic France. The disparity in populations between these two rival powers, and the British public’s reluctance to maintain a large standing army, made this external source of manpower of crucial importance. Whereas the majority of these forces were acting in the capacity of allies, ‘auxiliary’ forces were hired as well, and from the mid-century onwards, a small but steadily increasing number of German men would serve within British regiments or distinct formations referred to as ‘Foreign Corps’. Employing or allying with these troops would result in these Anglo- German armies operating not only on the European continent but in the American Colonies, Caribbean and within the British Isles as well. Within these multinational coalitions, soldiers would encounter and interact with one another in a variety of professional and informal venues, and many participants recorded their opinions of these foreign ‘brother-soldiers’ in journals, private correspondence, or memoirs. These commentaries are an invaluable source for understanding how individual Briton’s viewed some of their most valued and consistent allies – discussions that are just as insightful as comparisons made with their French enemies. -

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form

Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 1 Apply style tape to your dress form to establish the bust level. Tape from the left apex to the side seam on the right side of the dress form. 1 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 2 Place style tape along the front princess line from shoulder line to waistline. 2 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3A On the back, measure the neck to the waist and divide that by 4. The top fourth is the shoulder blade level. 3 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 3B Style tape the shoulder blade level from center back to the armhole ridge. Be sure that your guidelines lines are parallel to the floor. 4 Module 1 – Prepare the Dress Form Step 4 Place style tape along the back princess line from shoulder to waist. 5 Lesson Guide Princess Bodice Draping: Beginner Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 1 To find the width of your center front block, measure the widest part of the cross chest, from princess line to centerfront and add 4”. Record that measurement. 6 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 2 For your side front block, measure the widest part from apex to side seam and add 4”. 7 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 3 For the length of both blocks, measure from the neckband to the middle of the waist tape and add 4”. 8 Module 2 – Extract Measurements Step 4 On the back, measure at the widest part of the center back to princess style line and add 4”. -

Women's Clothing in the 18Th Century

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions A Peek Inside Mrs. Derby’s Clothes Press: Women’s Clothing in the 18th Century In the parlor of the Derby House is a por- trait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, wearing her finest apparel. But what exactly is she wearing? And what else would she wear? This edition of Pickled Fish focuses on women’s clothing in the years between 1760 and 1780, when the Derby Family were living in the “little brick house” on Derby Street. Like today, women in the 18th century dressed up or down depending on their social status or the work they were doing. Like today, women dressed up or down depending on the situation, and also like today, the shape of most garments was common to upper and lower classes, but differentiated by expense of fabric, quality of workmanship, and how well the garment fit. Number of garments was also determined by a woman’s class and income level; and as we shall see, recent scholarship has caused us to revise the number of garments owned by women of the upper classes in Essex County. Unfortunately, the portrait and two items of clothing are all that remain of Elizabeth’s wardrobe. Few family receipts have survived, and even the de- tailed inventory of Elias Hasket Derby’s estate in 1799 does not include any cloth- ing, male or female. However, because Pastel portrait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, c. 1780, by Benjamin Blythe. She seems to be many other articles (continued on page 8) wearing a loose robe over her gown in imitation of fashionable portraits. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

A Study on the Design and Composition of Victorian Women's Mantle

Journal of Fashion Business Vol. 14, No. 6, pp.188~203(2010) A Study on the Design and Composition of Victorian Women’s Mantle * Lee Sangrye ‧ Kim Hyejeong Professor, Dept. of Fashion Design, TongMyong University * Associate Professor, Dept. of Clothing Industry, Hankyong National University Abstract This study purposed to identify the design and composition characteristics of mantle through a historical review of its change and development focusing on women’s dress. This analysis was particularly focused on the Victorian age because the variety of mantle designs introduced and popularized was wider than ever since ancient times to the present. For this study, we collected historical literature on mantle from ancient times to the 19 th century and made comparative analysis of design and composition, and for the Victorian age we investigated also actual items from the period. During the early Victorian age when the crinoline style was popular, mantle was of A‐ line silhouette spreading downward from the shoulders and of around knee length. In the mid Victorian age from 1870 to 1889 when the bustle style was popular, the style of mantle was changed to be three‐ dimensional, exaggerating the rear side of the bustle skirt. In addition, with increase in women’s suburban activities, walking costume became popular and mantle reached its climax. With the diversification of design and composition in this period, the name of mantle became more specific and as a result, mantle, mantelet, dolman, paletot, etc. were used. The styles popular were: it looked like half-jacket and half-cape. Ornaments such as tassels, fur, braids, rosettes, tufts and fringe were attached to create luxurious effects. -

North of Perth

A LONG ROAD HOME The Life and Times of Grisha Sklovsky 1915-1995 by John Nicholson This book is dedicated to the memory of Chaja, also known as Anna Sklovsky, who placed her trust in justice and the rule of law and was betrayed by justice and the rule of law in a gas-chamber at Auschwitz. 2 CONTENTS Preface Introduction Chapter One Siberia Chapter Two Berlin Chapter Three Lyon Chapter Four The Czech Brigade Chapter Five England Chapter Six Waiting Chapter Seven Invasion Chapter Eight From Greece to Paris to America Chapter Nine Melbourne Chapter Ten Family, Friends and Europe Chapter Eleven Battlegrounds and the Antarctic Chapter Twelve New Directions and Multiculturalism Chapter Thirteen SBS Television Chapter Fourteen Of Camberwell and other battles Chapter Fifteen Moscow Chapter Sixteen Last Days Epilogue Notes Index 3 Introduction In the early years of the twentieth century, when the word pogrom [Russian: devastation] had entered the world‟s vocabulary, many members of a Russian Jewish family named Sklovsky were leaving their long-time homes within the Pale of Settlement.1 They were compelled to leave because, after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, experiments in half-hearted liberalism were abandoned and throughout the regimes of Alexander III [1881-1894] and Nicholas II [1894-1917] the Jews of Russia were subjected to endless persecution. As a result of the partitions of Poland in the eighteenth century more than a million Jews had found themselves within the Russian empire but permitted to live only within the Pale, the boundaries of which were determined in 1812. -

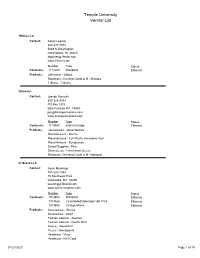

Temple University Vendor List

Temple University Vendor List 19Nine LLC Contact: Aaron Loomer 224-217-7073 5868 N Washington Indianapolis, IN 46220 [email protected] www.19nine.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1112269 Standard Effective Products: Otherwear - Shorts Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Stickers T-Shirts - T-Shirts 3Click Inc Contact: Joseph Domosh 833-325-4253 PO Box 2315 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 [email protected] www.3clickpromotions.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1114550 Internal Usage Effective Products: Housewares - Water Bottles Miscellaneous - Koozie Miscellaneous - Cell Phone Accessory Item Miscellaneous - Sunglasses School Supplies - Pen Short sleeve - t-shirt short sleeve Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Notepad 47 Brand LLC Contact: Kevin Meisinger 781-320-1384 15 Southwest Park Westwood, MA 02090 [email protected] www.twinsenterprise.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1013854 Standard Effective 1013856 Co-branded/Operation Hat Trick Effective 1013855 Vintage Marks Effective Products: Accessories - Gloves Accessories - Scarf Fashion Apparel - Sweater Fashion Apparel - Rugby Shirt Fleece - Sweatshirt Fleece - Sweatpants Headwear - Visor Headwear - Knit Caps 01/21/2020 Page 1 of 79 Headwear - Baseball Cap Mens/Unisex Socks - Socks Otherwear - Shorts Replica Football - Football Jersey Replica Hockey - Hockey Jersey T-Shirts - T-Shirts Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatpants Womens Apparel - Capris Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatshirt Womens Apparel - Dress Womens Apparel - Sweater 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce