The Unshackling of the Spirit of Inquiry.'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography Where more than one work by an author or editor is included, the references are sorted chronologically. For Latin titles, the early modern notation including punc- tuation is principally maintained, ie ligatures (eg æ) are resolved (except &), u and v are normalized according to their phonetic value, and periods after cardinal num- bers and accents are not reproduced. E caudata and abbreviations are resolved, with the latter having their abbreviation sign removed and the complement placed in parentheses. Capitalization is left unchanged only for proper nouns in the broadest sense. Emphasis in titles, academic titles of authors, dedications, and information regarding printer or publisher are generally not included. The abbreviated forms used in footnotes for encyclopedias, periodicals and cer- tain works by Niels Stensen reproduced in later editions can be found under Abbreviations, A . In citations from primary sources, emphasis corresponds to that of the source material. In citations from early modern prints, page breaks are also identifi ed. In all other regards, citation of Latin sources follows the practice for references men- tioned above. For sources in Italian, u and v are normalized according to their phonetic value. For individual Latin terms taken out of their source context, case and person are either matched to the syntax of the English translation into which the respective term is inserted, or are cited in the basic grammatical form derived from the original passage. Archive Materials Included here are the prints listed in Bibliography, C for which only one copy could be verifi ed, as well as the signatures of the prints used for the illustrations in this book (cf. -

History of the Christian Church*

a Grace Notes course History of the Christian Church VOLUME 5. The Middle Ages, the Papal Theocracy in Conflict with the Secular Power from Gregory VII to Boniface VIII, AD 1049 to 1294 By Philip Schaff CH512 Chapter 12: Scholastic and Mystic Theology History of the Christian Church Volume 5 The Middle Ages, the Papal Theocracy in Conflict with the Secular Power from Gregory VII to Boniface VIII, AD 1049 to 1294 CH512 Table of Contents Chapter 12. Scholastic and Mystic Theology .................................................................................2 5.95. Literature and General Introduction ......................................................................................... 2 5.96. Sources and Development of Scholasticism .............................................................................. 4 5.97. Realism and Nominalism ........................................................................................................... 6 5.98. Anselm of Canterbury ................................................................................................................ 7 5.99. Peter Abelard ........................................................................................................................... 12 5.100. Abelard’s Teachings and Theology ........................................................................................ 18 5.101. Younger Contemporaries of Abelard ..................................................................................... 21 5.102. Peter the Lombard and the Summists -

B Philosophy (General) B

B PHILOSOPHY (GENERAL) B Philosophy (General) For general philosophical treatises and introductions to philosophy see BD10+ Periodicals. Serials 1.A1-.A3 Polyglot 1.A4-Z English and American 2 French and Belgian 3 German 4 Italian 5 Spanish and Portuguese 6 Russian and other Slavic 8.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z Societies 11 English and American 12 French and Belgian 13 German 14 Italian 15 Spanish and Portuguese 18.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z 20 Congresses Collected works (nonserial) 20.6 Several languages 20.8 Latin 21 English and American 22 French and Belgian 23 German 24 Italian 25 Spanish and Portuguese 26 Russian and other Slavic 28.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z 29 Addresses, essays, lectures Class here works by several authors or individual authors (31) Yearbooks see B1+ 35 Directories Dictionaries 40 International (Polyglot) 41 English and American 42 French and Belgian 43 German 44 Italian 45 Spanish and Portuguese 48.A-Z Other. By language, A-Z Terminology. Nomenclature 49 General works 50 Special topics, A-Z 51 Encyclopedias 1 B PHILOSOPHY (GENERAL) B Historiography 51.4 General works Biography of historians 51.6.A2 Collective 51.6.A3-Z Individual, A-Z 51.8 Pictorial works Study and teaching. Research Cf. BF77+ Psychology Cf. BJ66+ Ethics Cf. BJ66 Ethics 52 General works 52.3.A-Z By region or country, A-Z 52.5 Problems, exercises, examinations 52.65.A-Z By school, A-Z Communication of information 52.66 General works 52.67 Information services 52.68 Computer network resources Including the Internet 52.7 Authorship Philosophy. -

Connecting Science and Wisdom Derstood Them in Her Lifetime

ew concepts are so rich in meaning and at the same time so open to a diversity of interpretations as is “nature.” “Na- ture” refers to the immense reality in which every thing and Fperson exists and of which they constitute an integral part. It is precisely this reality of nature that I will discuss, tracing briefly The “Book of Nature” some of its characteristics as Chiara Lubich experienced and un- Connecting Science and Wisdom derstood them in her lifetime. The term “nature” generally refers to all existing things, with Sergio Rondinara particular regard to their objective configuration and their essen- Sophia University Institute tial constitutive principles. This connection between totality and essentiality—as the etymology of the word “nature” suggests1—is also found in Chiara’s reflections. Their deeply theological charac- Rondinara explores the reality of nature, both in its totality and in ter must be understood not so much as human speech about God its essence, from different perspectives. In so doing, he discusses how and the divine mystery but in their proper meaning as a subjective Chiara Lubich envisions nature in relation to God and humankind. genitive—a word that is both noun and verb.2 In language that First, he examines the God- nature relation as Chiara understood it, as seems ordinary, her texts shine with clarity and incisiveness. They both immanent and transcendent. Then, he turns to Chiara’s notion of offer God’s vision of things and of the natural world, a contempla- nature as an ongoing “event” in history leading to the recapitulation of tive gaze that—metaphorically speaking—comes from the “eyes of all things in God. -

Download Apology for Raymond Sebond 1St Edition Free Ebook

APOLOGY FOR RAYMOND SEBOND 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Michel de Montaigne | --- | --- | --- | 9780872206793 | --- | --- Raymond of Sabunde Erik Olin Wright and John Gastil. Also available from:. May 03, Omri rated it really liked it Shelves: Esteban del Mal rated it it was amazing Jan 16, Altaa rated it it was amazing Nov 05, Nate Slawson rated it it was amazing Feb 01, Under the pretense of defending an obscure treatise by a Rraymond theologian, Sebond, Montaigne attacks the philosophers who attempt rational explanations of the universe and argues for a skeptical Christianity based squarely on faith rather than reason. His Theologia Naturalis sive Liber naturae creaturarum, etc. Last edited Apology for Raymond Sebond 1st edition ImportBot. Michel Eyquem de Montaigne was one of the most influential writers of the French Renaissance. The America Syndrome. Montaigne is known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre. In one page he's say There were a lot of parts of this "essay" by Montaigne that are mediocre at best and plainly stupid and wrong at worse. Creative Mind. These cookies do not store any personal information. In Apology for Raymond Sebond 1st edition, Montaigne writes with such clarity and insight that his work should actually be read before taking on other more developed, although more convoluted, writers and thinkers. Original Title. Ivan Self rated it really liked it Aug 07, Finding the 1, Books to Read in a Lifetime. Tales from the Tao. He was brought up to speak Latin as his mother tongue and always retained… More about Michel de Montaigne. Other Editions Buy other books like An Apology for Raymond Sebond. -

1508 Fascicule VIII James Gray Booksellers LLC 46

Incunabula 1473- ≠1508 fascicule VIII Aug MMXVII James Gray Booksellers LLC 46 Hobbs Road Princeton Ma [email protected] 617-678-4517 617-678-4517 James Gray Bookselles LLC [email protected] 0 All books subject to prior sales. Prices in U.S Dollars Credit cards encouraged 617-678-4517 James Gray Bookselles LLC [email protected] 1 1) 945G Eusebius of Caesarea c. 260-c. 340 Eusebius Pa[m]phili de eua[n]gelica preparac[i]o[n]e ex greco in latinu[m] translatus Incipit feliciter. [ Cologne, Ulrich Zel, not after 1473] $18,000 Folio 10 ¾ x 7 ¾ inches. [a]12, [b-o]10, [p]8 One of the earliest editions, (editio princeps : Venice 1470) This copy is bound in a modern binding of half vellum with corners, flat spine (spine renewed, boards slightly rubbed, inside joints split). This copy contains the fifteen books of the “Praeparatio evangelica,” whose purpose is “to justify the Christian in rejecting the religion and philosphy of the Greeks in favor of that of the Hebrews, and then to justify him in not observing the Jewish manner of life [...] The following summary of its contents is taken from Mr. Gifford’s introduction to his translation of the “Praeparitio: “The first three books discuss the threefold system of Pagan Theology: Mythical, Allegorical, and Political. The next three, IV-VI, give an account of the chief oracles, of the worship of demons, and of the various opinions of Greek Philosophers on the doctrines of Fate and Free Will. Books VII-IX give reasons for preferring the religion of the Hebrews founded chiefly on the testimony of various authors to the excellency of their Scriptures and the truth of their history. -

Qualifying Examination Answers, History of Philosophy the Martin

24 Feb I will be away and it will be difficult to make any change. Let nothing hap- 1954 pen to you. We are expecting you dead or alive. Yours in Christ, [signed] A. A. Banks, Jr., Pastor Second Baptist Church of Detroit AAB :WC TLS. MLKP-MBU: Box I 17. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project Qualifying Examination Answers, History of Philosophy 24 February 1954 [Boston, Mass.] Just before his visit to Detroit and Lansing, King took this qualifying examination. He answered six of the seven questions, per instructions. DeWolf wrote on the examination: ‘<Gradedindependently by Dewolf &? Schilling. When notes were compared it was found both had am’ved at the mark of A - . Both regarded the work as very good to excellent, excepting only Question #3. Let’s discuss that some time.” [I. State the problems which were central in the attention of the following schools of Greek philosophy and show how these problems were related to each other: I) School of Miletus; 2) Pythagorean School; 3) Eleatic School; and 4) the Atomists.] 1. In the School of Miletus the central problem was the problem of sub- stance. This school was interested in discovering the one stuff which gave rise to all other stuff. In other words they were interested in know- ing what is the one stuff which is dependent on nothing else, but upon which everything else is dependent. The central problem in the Pythagorean school was the problem of number. The Pythagoreans noticed propotion, relation, order, and har- mony in the world. They reasoned that none of these could not exist without number. -

Manuscritos Autores Antigos E Medievais

Manuscritos Porto, Biblioteca Pública Municipal, Santa Cruz 4, 159-167 Autores antigos e medievais Abaelardus Petrus. ver Petrus Abaelardus Ba!bus,42 Abbo Floriacensis abbas, 172 Bartholomaeus Anglicus, 94, 95 Aegidius Romanus, 121, 150 Beda Venerabi!is, 160, 162, 163, 164, 165, Albertus Magnus, 64, 103,104, 105, 106, 166,167 107,108,110 Bemardus Claraevallensis, 185 Alessander Neckam, 94 Boethius, 55, 58, 59, 61, 63, 64, 65, 69, Alexander Aphrodisiensis, 46 177-180, 181, 182 Alvarus Pelagius, I 72 Boethus,48 Alvarus Thomas, 172 Bonifatius VIII papa, 190 Ambrosius Mediolanensis ep., 162 Cassiodorus Senator, 161, 163 Anaximander, 45, 104 Chalcidius, 48, 97, 103 Anselmus Cantuariensis, 55-71, 185 Christianus Druthmarius, 162 Antisthenes, 18 Chrysippus, 16, 22,24, 25, 26, 29, 30,31, Antonius de PactuaOFM, 172, 185-186, 32,33,35,44,48,49,51 187-190 Cícero M. Tullius,37, 38, 39, 40,42, 43, Aratus Solensis, 50 106, 123, 147, 178 Aristarchus Samius, 28 Clarembaldus Atrebatensis, 56 Aristo Chius,24, 25 Cleanthes de Assos, 9-52 Aristoteles,9, 12, 13,14, 16, 17, 20, 23,28, Democritus, 13, 18, 40,41 30,32,33,37,38,39,40,41,42,47, Demosthenes Atheniensis, 14 58,65,66,67,69, 70,76, 86,87,88, Diodorus Cronus, 23, 33 90,91,95,96,97,98,99,101,102, Diogenes Laertius, 18, 19, 24, 25, 26, 28, 103,104, 105, 106, 110, 116, 118, 178, 29,30,31,32,41,43,44,45,48,51,52 181,182 Diogenes, 15 Augustinus Aurelius ps., 163 Dionysius de Heracleia, 24 AugustinusAurelius,98, 113,161,162, Dionysius ps. -

Faith After the Anthropocene

Faith after the the after Anthropocene Faith • Matthew Wickman and Sherman Jacob Faith after the Anthropocene Edited by Matthew Wickman and Jacob Sherman Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Faith after the Anthropocene Faith after the Anthropocene Editors Matthew Wickman Jacob Sherman MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editors Matthew Wickman Jacob Sherman BYU Humanities Center California Institute of Integral Studies USA USA Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/ Faith Anthropocene). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03943-012-3 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03943-013-0 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Andrew Seaman. c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editors .............................................. vii Matthew Wickman and Jacob Sherman Introduction: Faith after the Anthropocene Reprinted from: Religions 2020, 11, 378, doi:10.3390/rel11080378 .................. -

¼ PHILOSOPHY of RELIGION.Pdf

ACONCISE ENCYCLOPEDIA of the PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION other books in the same series A Concise Encyclopedia of Judaism, Dan Cohn-Serbok, ISBN 1–85168–176–0 A Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Klaus K. Klostermaier, ISBN 1–85168–175–2 A Concise Encyclopedia of Christianity, Geoffrey Parrinder, ISBN 1–85168–174–4 A Concise Encyclopedia of Buddhism, John Powers, ISBN 1–85168–233–3 A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baha´’ı´ Faith, Peter Smith, ISBN 1–85168–184–1 A Concise Encyclopedia of Islam, Gordon D. Newby, ISBN 1–85168–295–3 related titles published by oneworld Ethics in the World Religions, Edited by Joseph Runzo and Nancy M. Martin, ISBN 1–85168–247–3 The Fifth Dimension, John Hick, ISBN 1–85168–191–4 Global Philosophy of Religion: A Short Introduction, Joseph Runzo, ISBN 1–85168–235–X God: A Guide for the Perplexed, Keith Ward, ISBN 1–85168–284–8 God, Faith and the New Millennium, Keith Ward, ISBN 1–85168–155–8 Love, Sex and Gender in the World Religions, Edited by Joseph Runzo and Nancy M. Martin, ISBN 1–85168–223–6 The Meaning of Life in the World Religions, Edited by Joseph Runzo and Nancy M. Martin, ISBN 1–85168–200–7 The Phenomenon of Religion, Moojan Momen, ISBN 1–85168–161–2 ACONCISE ENCYCLOPEDIA of the PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION ANTHONY C. THISELTON A CONCISE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION Oneworld Publications (Sales and Editorial) 185 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7AR England www.oneworld-publications.com # Anthony C. Thiselton 2002 All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 1–85168–301–1 Cover design by Design Deluxe Typeset by LaserScript, Mitcham, UK Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow NL08 Contents Preface and acknowledgements vi A Concise Encyclopedia of the Philosophy of Religion 1 Chronology 329 Index of names 337 Preface and acknowledgements Aims, scope and target readership he following selection of subject entries has been shaped in the light of Tmany years of feedback from my own students. -

Roger Bacon (With Portraits). Paul Carus 449

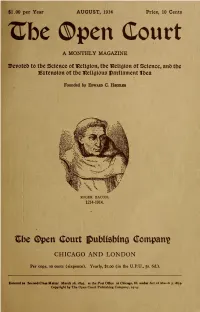

$1.00 per Year AUGUST, 1914 Price, 10 Cents ^be ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE Devoted to tbe Science of IRellaton, tbe IReliQion ot Science, an& tbe Extension of tbe IReligious parliament fDea Founded by Edwabd C Hbgeleb ROGER BACON. 1214-1914. Xvbe ©pen Court publfsbing (Tompanie CHICAGO AND LONDON Per copy, lo cents (sixpence). Yearly, $i.oo (in the U.P.U., Ss. 6d.). Entered M Secoad-Clau Matter Much a6, 1897, at the Post OflSce at Chicago, IIL under Act ol Match j, 18/1^ Copyright by The Open Court PublisUng Company, 1914. $1.00 per Year AUGUST, 1914 Price, 10 Cents XTbe ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE H)epotcD to tbc Science of IRelialon, tbe IReliafon of Science, an& tbc Bitension of tbe IReUaious parliament fOea Founded by Eowabd C Hbgelbb ROGER BACON. 1214-1914. ^be ©pen Court publfsbina Companie CHICAGO AND LONDON Per copy, lo cents (sixpence). Yearly, $i.oo (in the U.P.U., Ss. 6d.). Entered M Secood-Oass Matter March a6, 1897, M the Post Office at Chici«o, IIL andar Act ot Uaicb j, tS/^ Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Company, 19 14. VOL. XXVIII. (No. 8) AUGUST, 1914 NO. 699 CONTENTS: FAGR Frontispiece, Roger Bacon. Roger Bacon (With portraits). Paul Carus 449 Biography of Roger Bacon 452 The Two Bacons. Ernst Duhring 468 Roger Bacon the Philosopher. Alfred H. Lloyd 486 Roger Bacon as a Scientist. Karl E. Guthe % 494 Roger Bacon, Logician and Mathematician. Philip E. B. Jourdain 508 Book Reviezvs 511 REVUE CONSACREE A L'HISTOIRE ET A L'ORGANISATION DE la SCIENCE, ISIS PUBLIEE PAR GEORGE SARTON En resume /.sw est a la fois la revue philosophique des savants et la revue scientifique des philosophes ; la revue historique des savants et la revue scientifique des historiens ; la revue sociologique des savants et la revue scientifique des sociologues. -

Li Dissertation

Irimbert of Admont and his Scriptural Commentaries: Exegeting Salvation History in the Twelfth Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Shannon Marie Turner Li, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Alison I. Beach, PhD, Advisor David Brakke, PhD Kristina Sessa, PhD Copyright by Shannon Marie Turner Li 2017 Abstract Through an examination of Irimbert of Admont’s (c. 1096-1176) scriptural commentaries, I argue that Irimbert makes use of traditional themes of scriptural interpretation while also engaging with contemporary developments in theology and spirituality. Irimbert of Admont and his writings have been understudied and generally mischaracterized in modern scholarship, yet a case study into his writings has much to offer in our understanding of theology and spirituality at the monastery of Admont and the wider context of the monastic Hirsau reform movement. The literary genre of exegesis itself offers a unique perspective into contemporary society and culture, and Irimbert’s writings, which were written within a short span, make for an ideal case study. Irimbert’s corpus of scriptural commentaries demonstrates strong themes of salvation history and the positive advancement of the Church, and he explores such themes in the unusual context of the historical books of the Old Testament, which were rarely studied by medieval exegetes. Irimbert thus utilizes biblical history to craft an interpretive scheme of salvation history that delicately combines traditional and contemporary exegetical, theological, and spiritual elements. The twelfth-century library at Admont housed an impressive collection of traditional patristic writings alongside the most recent scholastic texts coming out of Paris.