Luis De Lucena Repetición De Amores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Challenge-Winter2009

V OLUME 49, ISSUE 3 CHALLENGE WINTER 2009 News for Lay Dominicans, Province of St Albert the Great From the President dent PC Delegates Start Search for New Leadership Fifteen delegates, plus elected and appointed officers Editor, Justice, Peace, and Care of Creation Promoter, Antiphons for Today were present at the October 2008 Provincial Council Corresponding Secretary, and Treasurer. Voting by O Wisdom – that comes from the Meeting in Plymouth, Michigan, to report on the activities Delegates will occur at the next Provincial Council gift of prudence of their communities. Provincial Promoter Fr Jim Motl Meeting, Oct. 22-25, 2009. O Adonai – That our Father leads said that he was heartened to learn that almost every com- Besides adoption of a new translation of the Rule , as each to His very being munity has a new member, and that younger people, as formulated by the Inter-Provincial Council earlier in O Root of Jesse – that we may well as more men, are joining the communities. the year, finishing touches were made to the By-Laws, respect the fountain of our roots President Ruth Kummer said that there have also been Handbook , and Guidelines and voted on in their final O Key of David – that our hearts growing pains, and that three chapters subdivided re- versions. Work was done on the Strategic Plan, headed open to Your gifts and strengthen cently. She recommended that in addition to ongoing by Chairman Ed Shea. Also discussed was the applica- one to close one’s hearts to faulting study in the cognitive domain, future training in the affec- tion process for the Province’s tax-exempt status, led O Dawn of Light – that you lead tive domain should be added to formation so as to en- by Treasurer Mary Lee Odders and her finance com- each from darkness with an open hance community life. -

Levitsky Dissertation

The Song from the Singer: Personification, Embodiment, and Anthropomorphization in Troubadour Lyric Anne Levitsky Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Anne Levitsky All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Song from the Singer: Personification, Embodiment, and Anthropomorphization in Troubadour Lyric Anne Levitsky This dissertation explores the relationship of the act of singing to being a human in the lyric poetry of the troubadours, traveling poet-musicians who frequented the courts of contemporary southern France in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. In my dissertation, I demonstrate that the troubadours surpass traditionally-held perceptions of their corpus as one entirely engaged with themes of courtly romance and society, and argue that their lyric poetry instead both displays the influence of philosophical conceptions of sound, and critiques notions of personhood and sexuality privileged by grammarians, philosophers, and theologians. I examine a poetic device within troubadour songs that I term ‘personified song’—an occurrence in the lyric tradition where a performer turns toward the song he/she is about to finish singing and directly addresses it. This act lends the song the human capabilities of speech, motion, and agency. It is through the lens of the ‘personified song’ that I analyze this understudied facet of troubadour song. Chapter One argues that the location of personification in the poetic text interacts with the song’s melodic structure to affect the type of personification the song undergoes, while exploring the ways in which singing facilitates the creation of a body for the song. -

Rewriting Dante: the Creation of an Author from the Middle Ages to Modernity

Rewriting Dante: The Creation of an Author from the Middle Ages to Modernity by Laura Banella Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date: _______________ Approved: ___________________________ Martin G. Eisner, Supervisor ___________________________ David F. Bell, III ___________________________ Roberto Dainotto ___________________________ Valeria Finucci Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Rewriting Dante: The Creation of an Author from the Middle Ages to Modernity by Laura Banella Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date: _________________ Approved: ___________________________ Martin G. Eisner, Supervisor ___________________________ David F. Bell, III ___________________________ Roberto Dainotto ___________________________ Valeria Finucci An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Laura Banella 2018 Abstract Rewriting Dante explores Dante’s reception and the construction of his figure as an author in early lyric anthologies and modern editions. While Dante’s reception and his transformation into a cultural authority have traditionally been investigated from the point of view of the Commedia, I argue that these lyric anthologies provide a new perspective for understanding how the physical act of rewriting Dante’s poems in various combinations and with other texts has shaped what I call after Foucault the Dante function” and consecrated Dante as an author from the Middle Ages to Modernity. The study of these lyric anthologies widens our understanding of the process of Dante’s canonization as an author and, thus, as an authority (auctor & auctoritas), advancing our awareness of authors both as entities that generate power and that are generated by power. -

La-Mia-Fede-Nei-Santi-Di-Ogni-Giorno

1 MARTINO CARBOTTI LA MIA FEDE nei Santi di ogni giorno Pugliesi Editore 2 Introduzione Non è assolutamente semplice per me, figlio, delineare la figura di mio padre: Ninuccio Carbotti. Non vi nascondo di averci pensato per molto tempo, dubbioso, circa i tanti aspetti su cui avrei dovuto soffermarmi e una delle domande che mi sono subito posto è stata: ma oltre alla figura di padre modello che io conoscevo, cos'altro conosco della vita di mio padre? E qui ho avuto delle perplessità ..... sì dico perplessità perché tutti i padri presumo hanno un determinato comportamento con i figli, dettato dal ruolo, c'è chi lo fà con più severità e chi meno, chi è pedante e chi meno, chi è accondiscendente e chi meno e via dicendo ma sicuramente tutti si apprestano a svolgere questo compito basilare con uno sconfinato e immenso amore !!! Ma un padre oltre a questo è anche un “uomo”ed è proprio il profilo umano, di uomo tra gli uomini, che mi ha portato ad iniziare questo lavoro, oserei dire di ricerca, esegetico, di tutti gli scritti e archiviazioni varie che con pazienza e passione certosina egli aveva iniziato ed implementato nei vari anni della sua vita. Ho avuto la fortuna di crescere in una famiglia molto unita, sotto tutti gli aspetti. Mio padre apparteneva a quelle belle famiglie di una volta, numerose: erano otto figli, madre, padre e “zizì” a carico (una zia di mia padre, sorella minore di mia nonna, la quale viveva sotto lo stesso tetto a causa di lievi problemi invalidanti) e come tradizione comanda, tutti i figli maschi e dico tutti nessuno escluso, hanno ereditato dal padre l'arte della lavorazione del legno. -

Volume-GUINIZZELLI.Pdf

PAROLE INTRODUTTIVE Carrubio collana di storia e cultura veneta diretta da Antonio Rigon 3 Dal latino “quadruvium” il nome Carrubio, antica contrada di Monselice, indica l’incrocio di quattro strade. È il luogo dell’incontro e dello scambio di vie e itinerari diversi. Così la collana: punto di incrocio di studi di storia e cultura nel Veneto e relativi al Veneto, crocevia secolare di uomini e culture. 1 FURIO BRUGNOLO COMUNE DI MONSELICE Assessorato alla Cultura BIBLIOTECA COMUNALE MONSELICE 2 PAROLE INTRODUTTIVE Da Guido Guinizzelli a Dante Nuove prospettive sulla lirica del Duecento Atti del Convegno di studi Padova-Monselice 10-12 maggio 2002 a cura di Furio Brugnolo Gianfelice Peron IL P O LIGRAFO 3 FURIO BRUGNOLO Staff editoriale e collaboratori nella realizzazione del Convegno Fabio Conte Sindaco di Monselice Riccardo Ghidotti Assessore alla Cultura Barbara Biagini Dirigente Settore Servizi alla persona Flaviano Rossetto Direttore della Biblioteca Antonella Baraldo, Antonella Carpanese Assistenti di Biblioteca Hanno contribuito alla realizzazione del Convegno: Università di Padova - Dipartimento di Romanistica Associazione Amici dei Musei Territorio Euganeo - Bassa Padovana Società Rocca di Monselice SOIMAT s.r.l. - Pisa Hanno partecipato, a diverso titolo, alla realizzazione del Convegno: Vittorina Baveo (†), Cristiano Cognolato, Maurizio De Marco, Giuseppe Ruzzante Per informazioni: Biblioteca di Monselice 35043 Monselice (Padova) - via San Biagio, 10 tel. 0429 72628 - fax 0429 711498 www.provincia.padova.it/comuni/monselice e-mail: -

San Mateo County Naturalization Index 1926-1945 San Mateo County 1926-1945

San Mateo County Naturalization Index 1926-1945 San Mateo County Genealogical Society 2000 San Mateo County Naturalization Index Volume 3 1926-1945 San Mateo County Genealogical Society ©2000 Project Co-ordinator/ Editor Cath MaddenTrindle Record Entry Cath Trindle, Ken & Pam Davis, Mary Lou Grunigen, Margaret Deal, Janice Marshall © September 2000 San Mateo County Genealogical Society Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 99-071151 Order Copies from the Publisher: San Mateo County Genealogical Society PO Box 5083 San Mateo CA 94402 Table of Contents San Mateo County 1926-1945 ........................................ ii Changes in Naturalization Laws .........................................iv Overview of San Mateo County Naturalization Records ......................v. Naturalization Index .................................................. 1 Bibliography ....................................................... 247 SMCGS Archives Project i San Mateo County Naturalization Index 1926-1945 San Mateo County 1926-1945 The two decades between 1926 and 1945 were a period of great growth in San Mateo County. Between 1930 and 1940 the population increased by nearly 50% from 77400 in 1930 to 111800 in 1940. New cities formed as the population grew including the incorporation of Belmont, Menlo Park and Woodside in 1927. Increasing transportation needs were answered by the opening of Mills Field (San Francisco Airport) in 1927 and the building of the San Mateo Hayward Bridge in 1929. The Great Depression was one of the reasons for an increase in population. Whereas previously immigrants might be likely to settle in San Francisco neighborhoods, now the lack of jobs and high rents led them to relocate to the peninsula. With much of the county still unincorporated it was still possible to find a strip of land and put up an inexpensive dwelling. -

Abbo of Fleury: 19, 122 Abbreviatio

Cambridge University Press 052130007X - The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism: The Middle Ages, Volume 2 Edited by Alastair Minnis and Ian Johnson Index More information Index Abbo of Fleury: 19, 122 Adenet le Roi abbreviatio (abbreviation): 55, 57, Berte aus grans pies´ : 449 58, 64, 449 Cleomades´ : 438 methods of: 48, 55 Les Enfances Ogier: 449 and amplificatio: 48, 58 ‘Ad habendam materiam’: 88 Abelard, Peter: 4, 21, 22, 536, 651 adnominatio: 87 Historia calamitatum: 543 Ælfric: 19, 318–20, 322–3 Abrams, M. H.: 285 Catholic Homilies: 318–20 Abu¯ ‘Ubayd al-Bakri:¯ 380 Grammar: 316 Acallam no Senorach´ : 303–4 Latin Preface to Saints’ Lives: accentus: 52 318 accessus ad auctores: 2, 52, 53, 102, Old English Preface to Saint’s 119–20, 123–5, 126, 128, Lives: 319, 322 129, 136, 138–9, 146–7, 148, Æsir: 35 7 150–2, 154, 157, 161, 162, Aelred of Rievaulx: 441 165, 166, 170, 182, 187, 190, aemulatio: 568 191, 192, 193, 197, 199, 203, Aeschines Socraticus: 679 211, 225, 227, 285, 366–7, Aeschylus: 219 369, 375, 378, 385, 404–5, Aesop: 40, 104, 155, 173, 195, 409, 412–14, 417, 418, 419, 375–7, 426, 436 492–3, 505, 509, 522, 529, affectus: 259, 272, 286, 655 530, 566, 568, 578, 583, affective poetics: 157 586–7, 588, 594–8, 608, 609, principalis affectio: 257, 259 610, 677 Afonso Eanes do Coton: 497 accessus ad satiricos: 225, Africa: 108 228 agens (author): 595–8 Accolti, Benedetto: 657 Agli, Peregrino: 646 Accursius: 655 Agliotti, Girolamo: 641 Achilles: 444, 684 Aimeric, Ars lectoria: 122–3 Achilles Tatius: 673, 678, 685 Aiol: 440 Acro, -

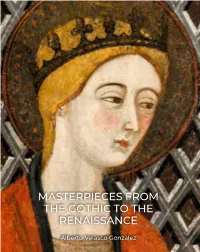

Masterpieces from the Gothic to the Renaissance

MASTERPIECES FROM THE GOTHIC TO THE RENAISSANCE Alberto Velasco Gonzàlez 1 4 MASTERPIECES FROM THE GOTHIC TO THE RENAISSANCE (1350-1550) Alberto Velasco Gonzàlez Galería Bernat Barcelona-Madrid 2020 4 MASTERPIECES FROM GOTHIC TO RENAISSANCE Contents Journey through the works: Hispanic painting th th from the 14 to the 16 century. 8 CATALOGUE JAUME CASCALLS Mourner . 28 JOAN DAURER Saint Margaret . 34 GONÇAL PERIS SARRIÀ Saint Catherine of Alexandria’s Debate with the Pagan Sages . 40 THE MASTER OF SAINT BARTHOLOMEW Epiphany . 46 JOAN REIXAC Mary Magdalene . 52 JOAN REIXAC Mary Magdalene . 58 JUAN SÁNCHEZ DE SAN ROMÁN Christ on the Way to Calvary . 64 CIRCLE OF FERNANDO GALLEGO St . Catherine of Alexandria’s Debate with the Pagan Sages . 70 CIRCLE OF THE MASTER OF CASTELSARDO Calvary . 76 FRANCESC DE OSONA Deposition of Christ Burial of Christ . 82 MASTER OF VALENCIA DE DON JUAN The Beheading of St . John the Baptist . 90 MASTER OF SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST Feast of Herod . 96 PAOLO DE SAN LEOCADIO Virgin and Child with the Infant St . John . 102 JUAN DE BORGOÑA AND WORKSHOP Calvary with the Mass of St . Gregory . .. 108 MIQUEL RAMELLS AND GUIOT BORGONYÓ Birth of the Virgin . 114 Bibliography. 120 Textos en castellano . 127 FOREWORD Dear friends, e are both delighted and excited to publish this new catalogue with the Galería Bernat’s latest acquisitions. In spite of the unfortunate times we W are all going through, and the uncertain days that lie ahead, our challenge is to study all of our works in great depth, and it is our wish to share the results of that study with you. -

24Th International Congress on Medieval Studies

Dear Colleague: It is my pleasure to invite you to the Twenty-Fourth International Congress on Medieval Studies to be held May 4-7,1989 on the campus of Western Michigan University under the sponsorship of the University's Medieval Institute. Among the highlights of this year's program are the symposium on Sutton Hoo: Fifty Years After, and the special sessions on Philosophy and the God of Abraham: In Memory of James Weisheipl.. Evening programs include a performance by the Christopher Newport Collegium Musicum of the Play of Herod, a medieval music-drama from the Reury Playbook, a performance of Trecento music by the Folger Consort, and the Staging of Resurrexit, a set of Easter plays by Lady Katherine Sutton, Abbess of Barking, performed by the Chicago Medieval Players. For fur ther details on these and other evening events, please consult the daily program schedule. I also call your attention to three special exhibits in the Fetzer Center. In anticipation of the 1990 publication of the Fine Art Faksimile Edition of the Books of Kells, sample pages of the forthcom ing edition will be on display in the lobby. The Association Villard de Honnecourt for the Interdis ciplinary Study of Medieval Technology, Science, and Art is sponsoring an exhibit of Villard's drawings on the second floor of Fetzer Center, and in Room 2016 Italian publishers will host a spe cial exhibit of books and publications on Italian art in connection with the special sessions on Italian Art and Architecture, 1000-1300, sponsored by the International Center of Medieval Art. -

Dominican Saints.Pmd

Dominican Calendar January Jan-3 The Most Holy Name of Jesus [C] Bl. Stephanie Quinzani (1457-1530)Italian, virgin, mystic, sister Jan-4 St. Zedíslava Berkiana (1221-1252) Lay Dominican and wife. Bohemian, she carefully raised four children and founded 2 Dominican priories, her charities, at times miraculously confirmed, abounded for the needy, the sick, and indigent families, she died in her husband’s arms. In 1989, through her intercession, a doctor was healed from a lengthy coma by a miracle. Canonized by John Paul II May 21, 1995. Jan-7 St. Raymond of Peñafort (1175-1275) [M]Spanish, priest, canonist, diplomat, Third Master of the Order, Church appointed patron of canonists, canonized in 1601. Jan-10 Bl. Gonsalvo of Amarante (+1259) Portuguese, priest, part-time hermit, miracle worker. Bl. Ann of the Angels. Jan-11 Bl. Bernard Scammacca (1430-1487) [M]Sicilian, priest, penitent, mystic. Jan-18 St. Margaret of Hungary (1242-1270) [F] for the nuns, Hungarian, virgin, royal princess, nun, mystic, canonized 1943. Jan-19 Bl. Andrew of Peschiera (1400-1485)Greco-Italian, priest, missionary to heretics. Jan-22 Bl. Anthony Della Chiesa (1394-1459)Italian, priest, renowned mystic and author. Jan-23 Bl. Henry Suso (Seuse) (+1366)German, priest, renowned mystic and author. Jan-27 Bl. Marcolinus of Forli (1317-1397)Italian, priest, ascetic. Jan-28 ST. THOMAS AQUINAS (1225-1274) [F]Italian, priest, renowned theologian, teacher, author of the “Summa Theologiae”, AKA “Angelic Doctor” and “Common Doctor” of the Church, Church appointed patron of students and Catholic schools, canonized 1323. Jan-29 Bl. Villana de’ Botti (1332-1361)Italian, wife and mother, contemplative, worker among the poor, Lay Dominican. -

E-201804.Pdf

REDAKCIJOS ŽODIS alandį pradedame Kristaus prisikėlimu – šv. Ve lykomis. Šią dieną, nugalėjęs mirtį ir nuodėmę, JėzusB pasirodė saviškiams; davė apaštalams Šventąją Dvasią nuodėmėms atleisti, pasiuntė juos į pasaulį Jį liudyti. Visą mėnesį skaitysime džiaugsmingus skaiti nius ir drauge su Jėzaus mokiniais mėginsime atpažinti Prisikėlusįjį. „Žmogus pats savo jėgomis nepajėgus atpažinti prisi kėlusio Jėzaus. Pats Jėzus atveria akis ir padaro, kad būtų regimas“, – rubrikoje „Kaip skaityti ir medituoti Dievo žodį“ rašo brolis Kazimieras Milaševičius OSB, anali zuodamas Evangelijos skaitinį apie Emauso mokinius. Jėzui atvėrus jų akis, mokiniai atranda ne tik Jėzų, bet ir Bažnyčią, ir gali drauge su visa bendruomene švęsti Eu charistiją, kurioje nuolat regimas prisikėlęs Jėzus. Nuo šio numerio kviečiame artimiau pažinti Katalikų Bažnyčios šventuosius atnaujintoje rubrikoje „Mėne sio šventasis“. Kiekvienos dienos pradžioje pateiksime po vieną šventojo mintį gilesniam apmąstymui. Balan dį mus kasdien lydės Bažnyčios mokytoja šv. Kotryna Sienietė, tvirtai tikėjusi Apvaizdos meile, su kuria Dievas Tėvas žvelgia į pasaulį ir savo Bažnyčią. Džiaugsmingų dienų prisikėlimo šviesoje! Indrė Klimkaitė MŪSŲ TIKĖJIMO TURTAI Viršelio paveikslas 2 Mėnesio šventoji 7 Kaip skaityti ir medituoti Dievo žodį 10 Evangelijos liudytojai šiomis dienomis 16 Istorinės datos 22 VIRŠELIO PAVEIKSLAS ANTONIJAUS IŠ FAENCOS „PRANAŠAS IZAIJAS IR ŠVENTASIS LUKAS“ (VARGONŲ PROSPEKTO DURELIŲ DETALĖ) „Todėl pats Viešpats duos jums ženklą: Štai ta mergelė laukiasi, – ji pagimdys sūnų ir pavadins jį Emanuelio vardu.“ (Iz 7, 14) agnificat“ viršelyje matome pavaizduotus du Šven „ tosios Dvasios įkvėptus asmenis, kurių gyvenimus skiriaM šimtmečiai, bet sieja nuostabus įvykis – Apreiškimo Švenčiausiajai Mergelei Marijai paslaptis. Pranašas Izaijas išskleidęs rodo mums užrašytus pranašystės žodžius, pats atsitraukdamas, likdamas nebylia figūra, vardu, įrašytu isto rijoje. -

January 31, 2021 – Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time January 31, 2021 Deuteronomy 18:15-20 Psalm 95:1-2, 6-9 1 Corinthians 7:32-35 Mark 1:21-28 “If today you hear his voice, harden not your hearts” St. Dominic’s is a Catholic Parish Inspired by Dominican Spirituality Igniting the Faith for the Salvation of Souls Mass Intentions Sun 01/31 7:00 a.m. (B) Rene Aquino 9:00 a.m. (D) Edmundo de Joya 11:00 a.m. (D) Ruth McElhaney 1:00 p.m. (D) Jim & Pat Kirksey Public Outdoor Mass 5:00 p.m. (T) People of the Parish Sunday: 11:00 a.m. Mon 02/01 6:45 a.m. (D) Reuben Garcia Small Parking Lot 8:15 a.m. (T) Lori Telepak & Family See Mass guidelines at Tues 02/02 6:45 a.m. (T) Jude Potter https://www.stdombenicia.org/covid19/ 8:15 a.m. (D) Paul Mullane Wed 02/03 6:45 a.m. (D) Tita Palermo 8:15 a.m. (D) Doris Hale Thank you to all our volunteers who make outdoor Thurs 02/04 6:45 a.m. (D) Richard S. Callao Masses possible. If you would like to help please 8:15 a.m. (D) Aurora Masbad email Teresa at [email protected]. Fri 02/05 6:45 a.m. (D) Fr. Victor Cavalli, O.P. 8:15 a.m. (D) Fr. Victor Cavalli, O.P. *Live-Stream Masses Sat 02/06 8:15 a.m. (H) Richard Nahm 5:00 p.m. (D) Agustin Leong WatchStDom.com Sun 02/07 7:00 a.m.