Magna International, Inc Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

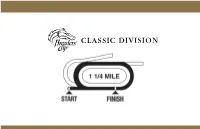

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Innovation and Quality for the International Automotive Industry

Automotive Industry Austria Innovation and Quality for the International Automotive Industry www.investinaustria.at INVEST IN AUSTRIA AUTOMOtive INDustrY 3h All of Europe by Air in Just 3 Hours Helsinki Oslo Stockholm Tallinn 2h Riga Moscow Copenhagen Dublin Vilnius Minsk Amsterdam London Berlin Warsaw Brussels 1h Prague Kiev Paris Luxembourg Bratislava Vienna Berne Kishinev Budapest Ljubljana Zagreb Belgrade Bucharest Madrid Sarajevo Lisbon Pristina Podgorica Sofia Rome Skopje Tirana Ankara Athens Austria’s central location in the heart of Europe makes it the ideal East-West business hub. 2 Invest in Austria Contents 5 The Red-White-Red Automotive Powerhouse 8 The Way Innovations Get into Cars 11 AVL: On the Research-Based Path to Success 12 A Competitive Edge through Knowledge 14 The Cluster: A Success Model with a Future 16 High-Tech Suppliers with Savvy 20 Miba Group: Progress from Passion 22 Non-Stop Production 24 GM Invests in a New Engine Generation 27 The Best Contact Partner for Business Location Issues Editorial: April 2011 Owner&Publisher: Austrian Business Agency, Opernring 3, A-1010 Wien Editor-in Chief: René Siegl Associate Editor: Maria Hirzinger, Karin Schwind-Derdak Design: www.november.at Photos: ACstyria Autocluster GmbH, APA, AVL LIST GmbH, BMW Motoren GmbH, GM Powertrain-Austria, HyCentA Research GmbH, Infineon Technologies Austria AG, KTM-Sportmotorcycle AG, MAN Nutzfahr- zeuge Österreich AG, Miba AG, Schaeffler Austria GmbH, Julius Silver Print: Gugler 3 AUTOMOtive INDustrY Engine production at General Motors Powertrain-Austria. The automobile producer General Motors has put its faith in its Austrian facility since 1982. At that time the first Opel plant opened in Vienna-Aspern. -

German Translation of Press Release Dated January 20, 2004 Magna Gibt

German translation of press release dated January 20, 2004 Magna gibt personelle Veränderungen an der Führungsspitze bekannt AURORA, Ontario - Wie die Magna International Inc. (TSX: MG.A, MG.B, NYSE: MGA) heute bekannt gab, hat Belinda Stronach ihre Ämter als President und Chief Executive Officer des Unternehmens mit sofortiger Wirkung niedergelegt. Frank Stronach übernimmt auf Interimsbasis die Position des President. Der Vorstand des Unternehmens hat unterdessen einen Sonderausschuss eingerichtet, der gemeinsam mit Frank Stronach innerhalb und ausserhalb des Konzerns nach einem Nachfolger für Frau Stronach suchen wird. Frank Stronach, Chairman von Magna, erklärte: "Im Namen des Vorstands und der Mitarbeiter des Unternehmens möchte ich Belinda meinen Dank für den herausragenden Beitrag aussprechen, den sie als President und CEO für unsere Aktionäre, Kunden und Beschäftigten geleistet hat." Stronach weiter: "Magna wird partnerschaftlich geführt. Andere Mitglieder im Managementteam, vor allem Manfred Gingl, Siegfried Wolf und Vince Galifi, werden nun grössere Aufgabenbereiche übernehmen." "Unter Frau Stronachs Führung hat Magna Wachstum und Gewinne in Rekordhöhe erzielt", so Ed Lumley, Lead Director im Vorstand des Unternehmens. "Sie hat einen wesentlichen Beitrag zum Wohle von Magna und seinen Tochtergesellschaften geleistet. Der Vorstand wünscht ihr für ihre berufliche Zukunft alles Gute." "Ich möchte allen Mitarbeitern von Magna für ihre Unterstützung danken", erklärte Belinda Stronach. "Magna und seine Tochtergesellschaften haben hervorragende Mitarbeiter und starke Führungsteams. Magna ist heute in einer guten Position, um auch in der Zukunft robuste Betriebsergebnisse zu zielen. Ich bin zuversichtlich, dass Magna auch weiterhin die Konkurrenz weit hinter sich lassen wird." Frau Stronach legte auch ihre Ämter als Vorstandsmitglied von Magna und als Vorstandsmitglied der Decoma International Inc., der Intier Automotive Inc. -

A N N U a L R E P O R T 2 0

337337 Magna Magna Drive Drive Aurora,Aurora, Ontario, Ontario, Canada Canada L4G L4G 7K1 7K1 Telephone:Telephone:(905) (905) 726-2462 726-2462 Fax:Fax: (905) (905) 726-7164 726-7164 Internet:Internet:www.magna.com www.magna.com ANNUALANNUAL REPORT REPORT 2001 2001 PrintedPrinted in Canada in Canada PRODUCT AND SERVICES DIRECTORY MAGNA STEYR DECOMA INTERNATIONAL INC. INTIER AUTOMOTIVE INC. Advanced R&D Concept Development Front and Rear Bumper Systems Interior Systems Magna Engineering Center (MEC) Total Vehicle Program Management I Spoilers and Grilles (MIC, Paint or Bright) Cockpit Systems I Design, concept & development capability Systems Sequencing and Logistics I GOP Moldings & Nerf Strips I Cockpit Modules for complete interior Complete Niche Vehicle Assembly I Energy Management Systems I Instrument Panels I Latest CAD systems linked by I Front & Rear Bumper Fascias I Leather Covered IP secured network Complete Vehicle Manufacturing I Complete Front & Rear End Modules I Consoles I Technical Illustration I Complete Space Frames I Floor Consoles I Program Management I Full Frames Greenhouse Systems I Glove Boxes I Seven design offices close to our I Sub-Assemblies I Backlite Moldings I Air Duct Systems customers (Germany, Austria, U.K.) I Body-In-White I Belt & Windshield Moldings I PSIR Doors Magna International Inc. is a leading I Painting I Pillar Appliques Magna Automotive Testing (A2LA) MOMENTUMI Assembly & Sequencing I Vehicle Assembly I Door Surround Moldings I Safety, Structural, Fatigue, and Durability global supplier of technologically I CKD Manufacturing I Roof Drip Moldings Overhead Systems Testing for Body and Interior Systems I Cowl Screens I Complete Overhead System OEM Engineering and Complete Vehicle and I Vehicle Ride Simulation, Noise, NVH and advanced automotive components, I Window Surround Module I Headliner Substrates Systems Capability Road Load Data Acquisition I Sun Visors I Concepts and Designs Body Side Systems I Computer Aided Engineering, FEA, systems and modules. -

Linde Equity Research TSX Performance Review

Linde Equity Research TSX Performance Review 2008 Q2: TSX has strong second quarter thanks to Energy, Materials Canadian market among best performers in the world in Q2 2008 Q2 Sector Returns Energy 24.21% Materials 17 . 16 % S&P/TSX Composite 8.37% Utilities 4.59% Industrials 3.42% Information Technology 2.04% Telecommunications Services 1. 3 1% Consumer Staples 0.17% -5.20% Financials -7.63% Health Care - 11. 4 5 % Consumer Discretionary -15% -10% -5% 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% • TSX 60 (large cap) stocks continued to 2008 Index Returns Q2 YTD outperform the broader market, a trend which S&P/TSX Composite 8.37% 4.58% began in Q2 2007. • The Canadian market again outperformed the US S&P/TSX 60 (Large Cap) 10.18% 6.76% market (S&P 500) in Q2. The S&P/TSX S&P/TSX Mid Cap 2.53% -2.32% Composite returned 8.4% versus -3.2% for the S&P/TSX Small Cap 2.85% -2.22% S&P 500 (-3.9% in Canadian dollar terms). • The dramatic spike in oil prices to around $140 per barrel by quarter-end drove strong Q2 Biggest Contributors Q2 Biggest Detractors performance in energy stocks throughout the Potash Corporation Manulife Financial world. The large weighting of Energy stocks in the Canadian market was the primary reason for Cdn Natural Resources CIBC Canada’s strong relative performance. EnCana Sun Life Financial • Materials stocks were also a strong driver of Suncor Energy Centerra Gold performance. The Canadian Materials sector performed better than comparable sectors in Husky Energy Royal Bank of Canada other countries due its higher exposure to Agrium Magna International fertilizer and gold stocks. -

Notice of Annual Meeting Management Information Circular/Proxy Statement

Notice of Annual Meeting Management Information Circular/Proxy Statement Annual Meeting May 4, 2011 BODY & CHASSIS SYSTEMS | POWERTRAIN SYSTEMS | EXTERIOR SYSTEMS www.magna.com SEATING SYSTEMS | INTERIOR SYSTEMS | VISION SYSTEMS | CLOSURE SYSTEMS | ROOF SYSTEMS | ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS | HYBRID & ELECTRIC VEHICLES/SYSTEMS | VEHICLE ENGINEERING & CONTRACT ASSEMBLY 24MAR201113335785 Magna International Inc. 337 Magna Drive 24MAR200901113112 Aurora, Ontario, Canada L4G 7K1 Telephone: (905) 726-2462 Legal Fax: (905) 726-7164 March 30, 2011 Dear Shareholder, I am pleased to invite you to attend Magna’s 2011 Annual Meeting of Shareholders on May 4, 2011 at 10:00 a.m. (Toronto time) at the Hilton Suites Toronto/Markham Conference Centre, 8500 Warden Avenue, Markham, Ontario, Canada. The business items which will be addressed at the annual meeting are set out in the notice of annual meeting and the accompanying proxy circular. We encourage you to vote your shares in person, or by phone, fax or internet, as described in the proxy circular. As in prior years, those not attending the annual meeting in person can access a simultaneous webcast through Magna’s website (www.magna.com). As you are aware, 2010 was a year of significant change for Magna. In August 2010, Magna completed the plan of arrangement and related transactions (the ‘‘Arrangement’’) announced in May 2010. The Arrangement, which was approved by over 75% of Magna’s disinterested shareholders, represented an historic milestone for Magna as it collapsed the dual-class share structure which had been in place since 1978. In conjunction with the Arrangement, the consulting, business development and business services agreements through which Frank Stronach has provided his knowledge and expertise to Magna and its divisions were amended to extend the expiry date of each agreement to December 31, 2014, after which they will automatically terminate. -

Magna International Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 40-F ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12 OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13(a) or 15(d) of THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018 Commission File Number 001-11444 Magna International Inc. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Not Applicable (Translation of Registrant’s name into English (if applicable) Province of Ontario, Canada (Province of other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 3714 (Primary Standard Industrial Classification Code number (if applicable) Not Applicable (I.R.S. Employer Identification Number (if applicable) 337 Magna Drive, Aurora, Ontario, Canada L4G 7K1 (905) 726-2462 (Address and telephone number of Registrant’s principal executive offices) Corporation Service Company, 1180 Avenue of the Americas, Suite 210 New York, New York 10036-8401 Telephone 212-299-5600 (Name, address (including zip code) and telephone number (including area code) of agent for service in the United States) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Shares New York Stock Exchange Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act. None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act. None For annual reports, indicate by check mark the information filed with this Form: ☒ Annual Information Form ☒ Audited Annual Financial Statements Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. -

Sun Life Guaranteed Investment Funds (Gifs)

Sun Life Guaranteed Investment Funds (GIFs) ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SUN LIFE ASSURANCE COMPANY OF CANADA December 31, 2015 Life’s brighter under the sun Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada is a member of the Sun Life Financial group of companies. © Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, 2016. 36D-0092-02-16 Table of Contents Independent Auditors' Report 3 Sun MFS Dividend Income 196 Sun Beutel Goodman Canadian Bond 5 Sun MFS Global Growth 200 Sun BlackRock Canadian Balanced 10 Sun MFS Global Total Return 204 Sun BlackRock Canadian Composite Equity 15 Sun MFS Global Value 209 Sun BlackRock Canadian Equity 20 Sun MFS Global Value Bundle 214 Sun BlackRock Canadian Equity Bundle 25 Sun MFS International Growth 218 Sun BlackRock Cdn Composite Eq Bundle 29 Sun MFS International Growth Bundle 222 Sun BlackRock Cdn Universe Bond 33 Sun MFS International Value 226 Sun Canadian Balanced Bundle 38 Sun MFS International Value Bundle 230 Sun CI Cambridge Canadian Equity 42 Sun MFS Monthly Income 234 Sun CI Cambridge Cdn Asset Allocation 46 Sun MFS US Equity 238 Sun CI Cambridge Global Equity 50 Sun MFS US Equity Bundle 242 Sun CI Cambridge/MFS Canadian Bundle 54 Sun MFS US Growth 246 Sun CI Cambridge/MFS Global Bundle 58 Sun MFS US Value 250 Sun CI Signature Diversified Yield II 62 Sun MFS US Value Bundle 255 Sun CI Signature High Income 66 Sun Money Market 259 Sun CI Signature Income & Growth 70 Sun NWQ Flexible Income 264 Sun Daily Interest 74 Sun PH&N Short Term Bond and Mortgage 268 Sun Dollar Cost Average Daily Interest 78 Sun RBC Global High -

Stronach Wins Riding-Barely Belinda Stronach Has a Job for I Have the Support of the the Next Four Years

Sending Your Teen To Us For 4 Days This Summer Could Save Their Life. Your local source for... Next Course Insurance Starts July 20th/04 Investments Wealth Management 905 727 4605 www.hsfinancial.ca 905-726-4132 Aurora’s Community Newspaper Representing email • [email protected] Vol. 4 No. 36 Week of June 29, 2004 905-727-3300 Stronach wins riding-barely Belinda Stronach has a job for I have the support of the the next four years. community. But only barely. “I’m in it for the long haul,” she Following Monday’s Federal told The Auroran in an exclusive election, in which Stronach battled interview. to victory in the new riding of Since January, Stronach has Newmarket-Aurora, the popular been running - sometimes literally blonde who made sure everyone - for this political position. knew she was born and raised in She put a spark into the newly the Newmarket-Aurora area, formed Conservative Party of breathed a sigh of relief. Canada when she announced she “I never took anything for grant- would seek the leadership. ed,” she told The Auroran. “I ran Suddenly, the woman who was this race believing I was always 10 Chief Executive Officer of Magna points behind.” International became a national And, apparently, she was. figure. Late numbers put her only She finished a respectable about 500 votes ahead of Liberal second behind Stephen Harper, Martha Hall Findlay and with only who lost out being Canada’s next a few polls to be heard from, sug- prime minister as the voters decid- gested Stronach was the narrow ed to stay “with the devil” they winner. -

Belinda Stronach? National Newspaper Coverage of the Conservative Party of Canada’S 2004 Leadership Race

Who Framed Belinda Stronach? National Newspaper Coverage of the Conservative Party of Canada’s 2004 Leadership Race Paper presented to the 2005 Canadian Political Science Association Conference London, Ontario June 4, 2005 Linda Trimble, Professor Political Science Department University of Alberta 12-26 HM Tory Bldg. Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2H4 [email protected] 2 Who Framed Belinda Stronach? National Newspaper Coverage of the Conservative Party of Canada’s 2004 Leadership Race Paper presented to the 2005 Canadian Political Science Association Conference London, Ontario June 4, 2005 Linda Trimble, Professor Political Science Department University of Alberta 12-26 HM Tory Bldg. Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2H4 [email protected] Abstract If masculine norms define political leadership roles and shape media coverage of leadership contests they are likely to be revealed by press coverage of serious challenges by women for the leadership of competitive political parties. The new Conservative Party of Canada’s inaugural leadership race featured such a candidate, Belinda Stronach. While Stronach lost the leadership to Stephen Harper on the first ballot, she ran a well-financed, staffed and organized campaign, enjoyed considerable backing from party insiders, and placed a respectable second. This paper reports the results of a content analysis of all news stories, opinion pieces, editorials and columns published about the leadership race in Canada’s national newspapers, the Globe and Mail and the National Post, from January 13 to March 22, 2004. It reveals striking differences in the amount of coverage accorded the candidates, as well as sexist framing and gendered evaluations of the female candidate. While Belinda Stronach’s campaign received a plethora of media attention, a considerable amount of it scrutinized her looks, wardrobe, sexual availability and personal background while mocking her leadership aspirations and deriding her qualifications for political office. -

Automotive Industry and COVID-19: End of the Road

Automotive industry and COVID-19: end of the road. The corona crisis has broken the very sophisticated supply chains in the automotive industry. Because of transport restrictions and closure of dealerships, it has almost become impossible to deliver cars to customers or for customers to order cars. Supply of components is also interrupted due to closure of plants for public health reasons (the accelerated rate of corona infections) or interrupted logistics. On top comes a general drop in demand: industrial production in the sector fell already by 12% in 2019. On the other hand, companies have announced to maintain the production of spare parts (crucial for public safety) and the R&D activities related to new powertrains. To deal with the consequences for the workers, most of the companies apply the nationally agreed conventions/rules on short-time work. COVID-19 has provoked an unprecedented crisis in the sector with an effective standstill of car production in Europe and a closed retail network. This will cause a dramatic negative demand shock. Vigorous measures will be needed to avoid plant closures and the permanent loss of jobs. Volkswagen - VW brand has suspended production at its German vehicle and component factories. VW plants in Pamplona (Spain), Setubal (Portugal) and Bratislava (Slovakia) are also closed. - Audi will stop production at its factories in Ingolstadt and Neckarsulm (Germany), Brussels, and Gyor (Hungary) by Monday, March 23 - Seat has halted its output - Skoda suspended production at its Czech plants for two weeks starting on Wednesday, March 18 - Lamborghini halted production in Italy - Porsche is stopping production for an initial period of two weeks, starting March 21 - Bentley is stopping production at its factory in Crewe, England, for four weeks starting March 21 - Due to shortage of supply from Europe, production is suspended in VW’s Russian factory in Kaluga and at the assembly line of VW’s contract manufacturer GAZ in Nizhny Novgorod PSA Group - PSA Group is closing its European factories until March 27. -

Magna Steyr India (Pvt)

CANADA SPECIAL COMPANY PROFILE Company: Company: MAGNA STEYR India (Pvt) Ltd OpenText Areas of Operation: Areas of Operation: Full vehicle development, Enterprise content manage- from sports cars to off-road ment, from document creation vehicles, flexible assembly to presentation to publishing. of vehicles, fuel tank compo- SOURCE: WWW.OPENTEXT.COM 5 nents, modules and complete 6 fuel systems, among others. SOURCE: WWW.MAGNASTEYR.COM hether you n these times of information explosion, it is said that drive a Porsche, content is king. In the world of enterprise content manage- WMercedes, Audi, Iment (ECM), OpenText is no less than king. or any other vehicle, In this age of all-digital and increasingly all-online content, you can be sure that everything must be sorted, grouped, tagged and stored for Magna Styer has online access, sharing, integration and broadcast—all these played an important are what OpenText does, and so much more. part in ensuring Set up in 1991 in Waterloo in southern Ontario, Canada, your drive is smooth. OpenText has become a global leader in ECM, helping organ- There isn’t an auto- isations in 114 countries manage their business content. Last mobile company, year, it earned a little less than a billion dollars in revenue. anywhere in the Through nearly 4450 employees, the company captures and world, that doesn’t preserves corporate memory, increases brand equity, auto- use parts, systems and mates processes, mitigates risk, manages compliance and assemblies designed, improves competitiveness. manufactured and inte- Its flagship product OpenText ECM has committed users grated by Magna Steyr. Its list across the globe, from car manufacturers to banks to the of customers is the virtual who’s media to real estate giants to law firms.