Appendix Charles C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kaplan & Sadock's Study Guide and Self Examination Review In

Kaplan & Sadock’s Study Guide and Self Examination Review in Psychiatry 8th Edition ← ↑ → © 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Philadelphia 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 USA, LWW.com 978-0-7817-8043-8 © 2007 by LIPPINCOTT WILLIAMS & WILKINS, a WOLTERS KLUWER BUSINESS 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 USA, LWW.com “Kaplan Sadock Psychiatry” with the pyramid logo is a trademark of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including photocopying, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. Printed in the USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sadock, Benjamin J., 1933– Kaplan & Sadock’s study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry / Benjamin James Sadock, Virginia Alcott Sadock. —8th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7817-8043-8 (alk. paper) 1. Psychiatry—Examinations—Study guides. 2. Psychiatry—Examinations, questions, etc. I. Sadock, Virginia A. II. Title. III. Title: Kaplan and Sadock’s study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry. IV. Title: Study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry. RC454.K36 2007 616.890076—dc22 2007010764 Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information presented and to describe generally accepted practices. However, the authors, editors, and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for any consequences from application of the information in this book and make no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the currency, completeness, or accuracy of the contents of the publication. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

Clinical Psychological Science: Then And

CPXXXX10.1177/2167702616673363LilienfeldThen and Now 673363research-article2016 Editorial Clinical Psychological Science 2017, Vol. 5(1) 3 –13 Clinical Psychological Science: © The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Then and Now DOI: 10.1177/2167702616673363 journals.sagepub.com/home/cpx Scott O. Lilienfeld Department of Psychology, Emory University In case you were wondering (and in case you weren’t), open to work drawn from a variety of subdisciplines the title of this article possesses a double meaning: It within basic psychological science, including physiologi- refers to both the Association for Psychological Science cal, evolutionary, comparative, cognitive, developmental, (APS) journal Clinical Psychological Science (CPS), of social, vocational, personality, cross-cultural, and mathe- which I am the new Editor, and to the field of clinical matical psychology, as well as from scientific disciplines psychological science at large. In this editorial, I examine that fall outside the traditional borders of psychological where our journal has been and where it is headed over science, including genetics, neuroscience, economics, the next several years, using past and ongoing develop- business, sociology, anthropology, microbiology, medi- ments in our field as context. Along the way, I will share cine, nursing, computer science, linguistics, and public my, at times, heterodox views of the field and explain health. Secondarily, CPS’s mission is translational, as we where I see CPS fitting into the broader domain of clini- aim to bridge the often yawning gap between basic and cal psychological science. In particular, I highlight CPS’s applied science relevant to clinical problems. long-standing emphases as well as a few novel ones. -

Clinical Manual of Cultural Psychiatry

Clinical Manual of Cultural Psychiatry Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Clinical Manual of Cultural Psychiatry Second Edition Edited by Russell F. Lim, M.D., M.Ed. Washington, DC London, England Note: The authors have worked to ensure that all information in this book is accurate at the time of publication and consistent with general psychiatric and medical standards, and that information concerning drug dosages, schedules, and routes of administration is accurate at the time of publication and consistent with standards set by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the general medical community. As medical research and practice continue to advance, however, therapeutic standards may change. Moreover, specific situations may require a specific therapeutic response not included in this book. For these reasons and because human and mechanical errors sometimes occur, we recommend that readers follow the advice of physicians directly involved in their care or the care of a member of their family. Books published by American Psychiatric Publishing (APP) represent the findings, conclusions, and views of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the policies and opinions of APP or the American Psychiatric Association. If you would like to buy between 25 and 99 copies of this or any other American Psychiatric Publishing title, you are eligible for a 20% discount; please contact Customer Service at [email protected] or 800-368-5777. If you wish to buy 100 or more copies of the same title, please e-mail us at [email protected] for a price quote. Copyright © 2015 American Psychiatric Association ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Manufactured in the United States of America on acid-free paper 181716151454321 Proudly sourced and uploaded by [StormRG] Second Edition Kickass Torrents | TPB | ET | h33t Typeset in Adobe Garamond and Helvetica. -

Inuit Concepts of Mental Health and Illness

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgment..........................................................................................................4 Summary ........................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................9 1.1 Outline of Report...............................................................................................10 1.2 The Inuit of Nunavik. .......................................................................................10 1.3 Psychiatric Epidemiology Among the Inuit..................................................13 1.4 Traditional Concepts of Illness........................................................................17 1.5 Contemporary Concepts of Mental Health and Illness...............................17 2. Methods......................................................................................................................21 2.1 Ethnographic Studies of the Meaning of Symptoms and Illness...............21 2.2 Study Sites..........................................................................................................22 2.3 Selection of Respondents & Sampling ...........................................................22 2.4 Procedure for Ethnographic Interviews ........................................................25 2.5 Data Analysis.....................................................................................................28 -

THE LEXICONS of PSYCHIATRY by the WORLD Heallh ORGANIZATION

THE LEXICONS Of PSYCHIATRY BY THE WORLD HEALlH ORGANIZATION Lexicon of Psgchiatric and Mental Health Terms Second Edition World Healt.h Organization Geneva 1994 Lexicon of Alcohol and Drug Terms World Health Organization Geneva 1997 Lexicon of Cross-Cultural Terms in Mental Health World Health Organization Gen('va 1994 S',~8)"~~ k II ~ I' II' ~ World Health Organization ""- ДЕКСИКОЛЫ ПСИХИАТРИИ ВСЕМИРНОЙ ОРГАНИЗАЦИИ ЗДРАВООХРАНЕНИЯ Лексикон осахоатрических о относящихся к психическому зуоровью терминов Второе оздание Лексикон терминов, относящихся к штт и уругом психоактивным среустоам Лексикон кросс-культуральных термопоо. относящихся к психическому зуеровью Перевод с английского под общей редакцией доц. В. Б. Позняка УДК 616.89(082) ББК 56.1я43 Л43 РиЬйЬеа Ьу йе \Уог1с1 НеаИЬ Оеагатайоп ипс1ег Ше ИИев Ьехкоп о/ рзускЫНс апй тепий кеаШ гегтз, 2Ы еД, Ьехкоп о/ акоЬЫ апй втщ 1еттл, Ьеххоп о/ сго85-си2(игаг ^е^т т тгпЫ ЬеаНН © Шт\й Неа№ Огеагагайоп, 1994,1997 ТЬе В1гес1ог-Сепега1 о{ Ше ШогЫ Неа11Ь Огеатгайоп Ьаз егаШей 1гапЕ1ааоп п$Ы& 1ог а опе-Уо1ите еШйоп т Низяап 1о ЗрЬеге РиЬизЫп§ Ноше, Иеу, тоЫсЬ 15 5о1е1у гезрогкМе 1ог Ше Низап еШйоа Перевод на русский язык и издание Лексиконов псгаиат- рии осуществлены благодаря гранту, предоставленному Генеральным директором Всемирной Организации Здраво охранения издательству «Сфера» (Киев), которое несет ответ ственность за издание книги на русском языке. 18ВК 966-7841-25-1 © Издательство «Сфера», ху дожественное оформле ние, 2001 Содержание Предисловие \т Лексикон психиатрических и относящихся -

Inussuk 2017 1 Bilag 6 Final-1

Bilag 6 til Fra passiv iagttager til aktiv deltager Bidrag til kortlægning af mekanismerne bag de seneste 150 års samfundsmæssige forandringer og gradvist øgede demokratisering i Grønland [Udgives kun elektronisk] Klaus Georg Hansen Nuuk 2017 Klaus Georg Hansen Bilag 6 til Fra passiv iagttager til aktiv deltager Bidrag til kortlægning af mekanismerne bag de seneste 150 års samfundsmæssige forandringer og gradvist øgede demokratisering i Grønland INUSSUK – Arktisk forskningsjournal 1 – 2017 – Bilag 6 Udgives kun elektronisk på hjemmesiden for Departementet for Uddannelse, Kultur Forskning og Kirke. 1. udgave, 1. oplag Nuuk, 2017 Copyright © Klaus Georg Hansen samt Departementet for Uddannelse, Kultur, Forskning og Kirke, Grønlands Selvstyre Uddrag, herunder figurer, tabeller og citater, er tilladt med tydelig kildeangivelse. Skrifter, der omtaler, anmelder, citerer eller henviser til denne publikation, bedes venligst tilsendt. Skriftserien INUSSUK udgives af Departementet for Uddannelse, Kultur, Forskning og Kirke, Grønlands Selvstyre. Formålet med denne skriftserie er at formidle resultater fra forskning i Arktis, såvel til den grønlandske befolkning som til forskningsmiljøer i Grønland og det øvrige Norden. Skriftserien ønsker at bidrage til en styrkelse af det arktiske samarbejde, især inden for humanistisk, samfundsvidenskabelig og sundhedsvidenskabelig forskning. Redaktionen modtager gerne forslag til publikationer. Redaktion Forskningskoordinator Najâraq Paniula Departementet for Uddannelse, Kultur, Forskning og Kirke Grønlands Selvstyre Postboks 1029, 3900 Nuuk, Grønland Telefon: +299 34 50 00 E-mail: [email protected] Publikationer i INUSSUK serien kan rekvireres ved henvendelse til Forlaget Atuagkat ApS Postboks 216 3900 Nuuk, Grønland Email: [email protected] Hjemmeside: www.atuagkat.gl Bilag 6 til Fra passiv iagttager til aktiv deltager Indledning Både selve PhD afhandlingen og værket her bygger på syv artikler, som jeg har skrevet. -

Factors Influencing University Sport Participation Among Rural and Remote First Nations Athletes in Manitoba

Factors Influencing University Sport Participation among Rural and Remote First Nations Athletes in Manitoba by Nickolas J. Kosmenko A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Applied Health Sciences University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2021 by Nickolas J. Kosmenko ii Abstract This research focused on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Call to Action 90(ii): “[a]n elite athlete development program for Aboriginal athletes” (TRC, 2015, p. 10). Numerous barriers impede Indigenous peoples’ sport participation (e.g., racism, cultural exclusion, few Indigenous coaches, geographic isolation of reserves). University sport programs can be helpful in this regard by providing access to sport resources (e.g., expert coaches, athletic therapists, sport nutritionists, sport psychologists, quality facilities and equipment) yet many obstacles affect university education for Indigenous students (e.g., racism, cultural irrelevance, limited academic direction in communities). Approximately 18% of people in Manitoba identify as Indigenous, suggesting efforts to overcome barriers to university sport/education would be impactful. Using socioecological frameworks and following an Indigenous research paradigm, the overarching focus of this research was to identify factors influencing university sport participation specifically among rural and remote First Nations athletes in Manitoba. Chapter 5 used conversational interviews to gather insights from rural and remote First Nations athletes at the high school level, as well as their coaches and teachers. Similar methods were used in Chapter 6, but with university-level athletes, their coaches, and university athlete alumni. Due to the importance of Indigenous coaches to athletic development of Indigenous athletes, Chapter 7 used conversational interviews to examine the factors influencing Canadian First Nations coaches’ coaching paths. -

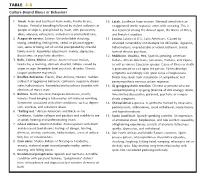

Table 5-8 for Examples (2, 14, 37, 112)

M05_MURR8663_08_SE_CH05.QXD 5/27/08 10:19 AM Page 131 Chapter 5 Sociocultural Influences 131 Influences of Culture on Health dark and light, hot and cold, hard and soft, or male and fe- male. An excess or shortage of elements in either direction causes discomfort and illness. CONCEPTS OF ILLNESS Many cultures explain the cause of and treatment for illness in one or Because every culture is complex, it can be difficult to deter- several of the following categories (2, 14, 37, 112): mine whether health and illness are the result of cultural or other elements, such as physiologic or psychological factors. Yet there are 1. Natural: Weather changes, bad food, or contaminated water numerous accounts of the presence or absence of certain diseases cause illness. in certain cultural groups and reactions to illness that are cultur- 2. Supernatural: The gods, demons, or spirits cause illness as pun- ally determined. ishment for faulty behavior, violation of the religious or ethi- Culture-bound illness or syndrome refers to disorders re- cal code, or an act of omission to a deity; or as a result of black stricted to a particular culture because of certain psychosocial charac- magic, voodoo, or evil incantation of an enemy or sorcerer. teristics of the people in the group or because of cultural reactions to the 3. Metaphysical: Health is maintained when nature and the body malfunctioning biological or psychological processes (2, 37, 112). See operate within a delicate balance between two opposites, such Table 5-8 for examples (2, 14, 37, 112). Culture and climate in- as Am and Duong (Vietnamese), yin and yang (Chinese), fluence food availability, dietary taboos, and methods of hygiene, which in turn affect health, as do cultural folkways. -

Academic Achievement and Minority Individuals

A-Jackson.qxd 7/12/2006 2:10 PM Page 1 A achievement gaps between certain racial or ethnic groups ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT on standardized tests in different subject areas and across AND MINORITY INDIVIDUALS grade levels. Other measures of academic achievement, such as grades and class rankings, show similar differ- The academic achievement of some minority individ- ences in minority and majority achievement. uals and groups remains a ubiquitous and seemingly Beyond the consistency of the disparities in minor- intractable problem in the United States. The problem ity and majority achievement, it is by no means clear is usually defined in terms of mean differences in what these discrepant scores really mean. To character- standardized achievement test scores between certain ize racial and ethnic differences as minority differences racial or ethnic groups. There is good reason for con- suggests that these groups have had similar experiences cern because on virtually every measure of academic and that these experiences influence their behavior in achievement, African American, Latino, and Native a similar way. However, this is not the case. There is American students, as a group, score significantly tremendous variability within and across racial and lower that their peers from European backgrounds. ethnic groups even though they are ascribed minority Moreover, it appears that gaps first manifest early in status in U.S. society. For example, native-born African school, broaden during the elementary school years, Americans and immigrants of African ancestry are sim- and remain relatively fixed during the secondary ilar in terms of race and minority status, but they have school years. -

“Cultura Política Nicaragüense” Por El Dr. Emilio Álvarez Montalván

0 No. 78 – Octubre 2014 ISSN 2164-4268 revista dedicada a documentar asuntos referentes a Nicaragua CONTENIDO INFORMACIÓN EDITORIAL ............................................................................................... 4 NUESTRA PORTADA ............................................................................................................. 5 La Camerata Bach .......................................................................................................................................... 5 DE NUESTROS LECTORES .................................................................................................. 8 DEL ESCRITORIO DEL EDITOR ...................................................................................... 11 Guía para el Lector ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Reorganización de Revista de Temas Nicaragüenses ........................................................................................ 16 ENSAYOS ............................................................................................................................... 19 Antidio Cabal y el Historicismo marxista de una época .................................................................................. 20 Manuel Fernández Vílchez El español americano de El Güegüence o Macho-Ratón .................................................................................. 26 Enrique Balmaseda Maestu La Beata Nicaragüense Sor María Romero .................................................................................................. -

Johan Wedel: Bridging the Gap Between Western and Indigenous Medicine in Eastern Nicaragua

Johan Wedel: Bridging the Gap between Western and Indigenous Medicine in Eastern Nicaragua Bridging the Gap between Western and Indigenous Medicine in Eastern Nicaragua Johan Wedel University of Gothenburg, [email protected] ABSTRACT In Nicaragua there are attempts, at various levels, to bridge the gap between Western and indigenous medicine and to create more equal forms of therapeutic cooperation. This article, based on anthropological fieldwork, focuses on this process in the North Atlantic Autonomous Region, a province dominated by the Miskitu people. It examines illness beliefs among the Miskitu, and how therapeutic cooperation is understood and acted upon by medical personnel, health authorities and Miskitu healers. The study focuses on ailments locally considered to be caused by spirits and sorcery and problems that fall outside the scope of biomedical knowledge. Of special interest is the mass-possession phenomena grisi siknis where Miskitu healing methods have been the preferred alternative, even from the perspective of the biomedical health authorities. The paper shows that Miskitu healing knowledge is only used to compensate for biomedicine’s failure and not as a real alternative, despite the intentions in the new Nicaraguan National Health Plan. This article calls for more equal forms of therapeutic cooperation through ontological engagement by ongoing negotiation and mediation between local and biomedical ways of perceiving the world. KEYWORDS: Miskitu, medical pluralism, healing, grisi siknis, Nicaragua Introduction Today, in most complex societies, various healing systems exist parallel with biomedicine (Western medicine).1 Although these systems may collaborate, biomedicine usually ANTHROPOLOGICAL NOTEBOOKS 15 (1): 49–64. ISSN 1408-032X © Slovene Anthropological Society 2009 1 Anthropological fieldwork was carried out in the Eastern Nicaraguan city of Puerto Cabezas, in the regional capital of the RAAN, for a total period of eleven months during 2005–2008, and mainly funded by the Swedish Research Council (427–2005–8695).