Books in Book Towns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 1998-1999 JUSTIN GUARIGLIA Children Along the Streets of Jakarta, Indonesia, Welcome President and Mrs

M E S S A G E F R O M J I M M Y C A R T E R ANNUAL REPORT 1998-1999 JUSTIN GUARIGLIA Children along the streets of Jakarta, Indonesia, welcome President and Mrs. Carter. WAGING PEACE ★ FIGHTING DISEASE ★ BUILDING HOPE The Carter Center One Copenhill Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5100 Fax (404) 420-5145 www.cartercenter.org THE CARTER CENTER A B O U T T H E C A R T E R C E N T E R C A R T E R C E N T E R B O A R D O F T R U S T E E S T H E C A R T E R C E N T E R M I S S I O N S T A T E M E N T Located in Atlanta, The Carter Center is governed by its board of trustees. Chaired by President Carter, with Mrs. Carter as vice chair, the board The Carter Center oversees the Center’s assets and property, and promotes its objectives and goals. Members include: The Carter Center, in partnership with Emory University, is guided by a fundamental houses offices for Jimmy and Rosalynn commitment to human rights and the alleviation of human suffering; it seeks to prevent and Jimmy Carter Robert G. Edge Kent C. “Oz” Nelson Carter and most of Chair Partner Retired Chair and CEO resolve conflicts, enhance freedom and democracy, and improve health. the Center’s program Alston & Bird United Parcel Service of America staff, who promote Rosalynn Carter peace and advance Vice Chair Jane Fonda Charles B. -

Open Merfeldlangston.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of French and Francophone Studies THE VILLAGES DU LIVRE: LOCAL IDENTITY, CULTURAL POLITICS, AND PRINT CULTURE IN CONTEMPORARY FRANCE A Thesis in French by Audra Lynn Merfeld-Langston © 2007 Audra Lynn Merfeld-Langston Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2007 The thesis of Audra Lynn Merfeld-Langston was reviewed and approved* by the following: Willa Z. Silverman Associate Professor of French and Francophone Studies and Jewish Studies Thesis Advisor Chair of Committee Thomas A. Hale Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of African, French, and Comparative Literature Head of the Department of French and Francophone Studies Greg Eghigian Associate Professor of Modern European History Jennifer Boittin Assistant Professor of French, Francophone Studies and History and Josephine Berry Weiss Early Career Professor in the Humanities *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Over the past several decades, the cultural phenomenon of the villages du livre has exploded throughout the Hexagon. Taking their cue from the original book town, Hay-on-Wye, in Wales, rural French communities once in danger of disappearing have reclaimed their economic future and their heritage. Founded in 1961, Hay-on-Wye has served as a model for other towns to establish a used book trade, organize literary festivals, and promote the practice of traditional book arts that include calligraphy, binding, paper-making, and printing. In the French villages du livre of Bécherel (Bretagne), Montolieu (Languedoc), Fontenoy-la-Joûte (Lorraine), Montmorillon (Poitou-Charentes), and La Charité-sur-Loire (Bourgogne), ancillary enterprises such as museums, bookstores, cafés, and small hotels now occupy buildings that had stood vacant for years. -

Concept and Types of Tourism

m Tourism: Concept and Types of Tourism m m 1.1 CONCEPT OF TOURISM Tourism is an ever-expanding service industry with vast growth potential and has therefore become one of the crucial concerns of the not only nations but also of the international community as a whole. Infact, it has come up as a decisive link in gearing up the pace of the socio-economic development world over. It is believed that the word tour in the context of tourism became established in the English language by the eighteen century. On the other hand, according to oxford dictionary, the word tourism first came to light in the English in the nineteen century (1811) from a Greek word 'tomus' meaning a round shaped tool.' Tourism as a phenomenon means the movement of people (both within and across the national borders).Tourism means different things to different people because it is an abstraction of a wide range of consumption activities which demand products and services from a wide range of industries in the economy. In 1905, E. Freuler defined tourism in the modem sense of the world "as a phenomena of modem times based on the increased need for recuperation and change of air, the awakened, and cultivated appreciation of scenic beauty, the pleasure in. and the enjoyment of nature and in particularly brought about by the increasing mingling of various nations and classes of human society, as a result of the development of commerce, industry and trade, and the perfection of the means of transport'.^ Professor Huziker and Krapf of the. -

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism 1 Cover photo: Lancaster Boulevard in Lancaster, California. Source: City of Lancaster. Photo by Tamara Leigh Photography. Street design by Moule & Polyzoides. 25 GREAT IDEAS OF NEW URBANISM Author: Robert Steuteville, CNU Senior Dyer, Victor Dover, Hank Dittmar, Brian Communications Advisor and Public Square Falk, Tom Low, Paul Crabtree, Dan Burden, editor Wesley Marshall, Dhiru Thadani, Howard Blackson, Elizabeth Moule, Emily Talen, CNU staff contributors: Benjamin Crowther, Andres Duany, Sandy Sorlien, Norman Program Fellow; Mallory Baches, Program Garrick, Marcy McInelly, Shelley Poticha, Coordinator; Moira Albanese, Program Christopher Coes, Jennifer Hurley, Bill Assistant; Luke Miller, Project Assistant; Lisa Lennertz, Susan Henderson, David Dixon, Schamess, Communications Manager Doug Farr, Jessica Millman, Daniel Solomon, Murphy Antoine, Peter Park, Patrick Kennedy The 25 great idea interviews were published as articles on Public Square: A CNU The Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) Journal, and edited for this book. See www. helps create vibrant and walkable cities, towns, cnu.org/publicsquare/category/great-ideas and neighborhoods where people have diverse choices for how they live, work, shop, and get Interviewees: Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Jeff around. People want to live in well-designed Speck, Dan Parolek, Karen Parolek, Paddy places that are unique and authentic. CNU’s Steinschneider, Donald Shoup, Jeffrey Tumlin, mission is to help build those places. John Anderson, Eric Kronberg, Marianne Cusato, Bruce Tolar, Charles Marohn, Joe Public Square: A CNU Journal is a Minicozzi, Mike Lydon, Tony Garcia, Seth publication dedicated to illuminating and Harry, Robert Gibbs, Ellen Dunham-Jones, cultivating best practices in urbanism in the Galina Tachieva, Stefanos Polyzoides, John US and beyond. -

Frank Bowling Cv

FRANK BOWLING CV Born 1934, Bartica, Essequibo, British Guiana Lives and works in London, UK EDUCATION 1959-1962 Royal College of Art, London, UK 1960 (Autumn term) Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1958-1959 (1 term) City and Guilds, London, UK 1957 (1-2 terms) Regent Street Polytechnic, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Image in Revolt, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1963 Frank Bowling, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1966 Frank Bowling, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1971 Frank Bowling, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, USA 1973 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1973-1974 Frank Bowling, Center for Inter-American Relations, New York, New York, USA 1974 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1975 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1976 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Watson/de Nagy and Co, Houston, Texas, USA 1977 Frank Bowling: Selected Paintings 1967-77, Acme Gallery, London, UK Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1979 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1980 Frank Bowling, New Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1981 Frank Bowling Shilderijn, Vecu, Antwerp, Belgium 1982 Frank Bowling: Current Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, -

Cartographic Perspectives Information Society 1

Number 53, Winterjournal 2006 of the Northcartographic American Cartographic perspectives Information Society 1 cartographic perspectives Number 53, Winter 2006 in this issue Letter from the Editor INTRODUCTION Art and Mapping: An Introduction 4 Denis Cosgrove Dear Members of NACIS, FEATURED ARTICLES Welcome to CP53, the first issue of Map Art 5 Cartographic Perspectives in 2006. I Denis Wood plan to be brief with my column as there is plenty to read on the fol- Interpreting Map Art with a Perspective Learned from 15 lowing pages. This is an important J.M. Blaut issue on Art and Cartography that Dalia Varanka was spearheaded about a year ago by Denis Wood and John Krygier. Art-Machines, Body-Ovens and Map-Recipes: Entries for a 24 It’s importance lies in the fact that Psychogeographic Dictionary nothing like this has ever been kanarinka published in an academic journal. Ever. To punctuate it’s importance, Jake Barton’s Performance Maps: An Essay 41 let me share a view of one of the John Krygier reviewers of this volume: CARTOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUES …publish these articles. Nothing Cartographic Design on Maine’s Appalachian Trail 51 more, nothing less. Publish them. Michael Hermann and Eugene Carpentier III They are exciting. They are interest- ing: they stimulate thought! …They CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONS are the first essays I’ve read (other Illinois Historical Aerial Photography Digital Archive Keeps 56 than exhibition catalogs) that actu- Growing ally try — and succeed — to come to Arlyn Booth and Tom Huber terms with the intersections of maps and art, that replace the old formula REVIEWS of maps in/as art, art in/as maps by Historical Atlas of Central America 58 Reviewed by Mary L. -

News Updates Please Email To

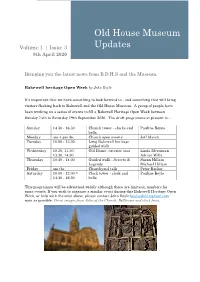

Old House Museum Volume 1 | Issue 3 Updates 9th April 2020 Bringing you the latest news from B.D.H.S and the Museum. Bakewell heritage Open Week by John Boyle It's important that we have something to look forward to - and something that will bring visitors flocking back to Bakewell and the Old House Museum. A group of people have been working on a series of events to fill a Bakewell Heritage Open Week between Sunday 13th to Saturday 19th September 2020. The draft programme at present is: - Sunday 14.30 - 16.30 Church tower - clocks and Pauline Boyne bells Monday am + pm tbc Church open events Jeff Marsh Tuesday 10.00 - 13.00 Long Bakewell heritage guided walk Wednesday 10.30, 11.30, Old House, exterior tour Linda Merriman 13.30, 14.30 Adrian Wills Thursday 10.30 - 14.00 Guided walk - Secrets & Susan Hillam Legends Michael Hillam Friday am tbc Churchyard talk Peter Barker Saturday 10.00 - 12.00 = Clock tower - clock and Pauline Boyle 14.30 - 16.30 bells This programme will be advertised widely although there are limits on numbers for some events. If you wish to organise a similar event during this Bakewell Heritage Open Week, or help with the ones above, please contact John Boyle [email protected] soon as possible. Great images from John of the Church, Bellframe and clock front. 2 Clock front Susan Hillam leads 'Secrets & Legends" Bakewell businesses project - from George Challenger Members might like to improve the project described below by adding or correcting information on shops and businesses to the tables I have prepared. -

Listen to the Voice of God in the Voice of Youth Because They Will Tell Us What They Expect of the Church

Year XI - n. 57 August–October 2018 Figlie di San Paolo - Casa generalizia Via San Giovanni Eudes, 25 - 00163 Roma [email protected] - www.paoline.org Listen to the voice of God in the voice of youth because they will tell us what they expect of the Church. Bishop Raúl Biord Castillo of La Guaira, Venezuela Foto: Štěpán Rek Summary DEAREST SISTERS... PAULINE PANORAMA The Circumscriptions Italy: Inauguration of Regina Apostolorum Hospital’s Multi-Purpose Hall Celebrating the Sunday of the Word in Prison Bolivia: International Book Fair Congo: Inauguration of an FSP Apostolic Center in Matadi Germany: Frankfurt Book Fair Great Britain: Ecumenical Award Pakistan: “Jesus calls you to serve” Peru: Recounting the Bible to Children Philippines: Cardinal Sin Catholic Book Awards Romania: 25 Years of Pauline Presence Our studies Pastoral Communication Through Films Bridging the Digital Divide in Nigeria THE SYNOD ON YOUNG PEOPLE Synod in Full Swing MOVING Ahead WITH Thecla Woman Associated to Priestly Zeal SHARING OUR STORIES My Vocation AGORÀ OF Communications Virtual and Real: An Anthropological Change? Calendar of the General Government THE PAULINE FAMILY Korea: 1st Formation Course on the Charism of the Pauline Family Italy: 22nd Course on the Pauline Charism Italy: Good Shepherd Sisters: 80th Anniversary of Foundation IN THE SPOTLIGHT Window on the Church Sacred Music: 18th Edition of Anima Mundi Digitization of the World’s Oldest Library Peace Journalism Takes Center Stage in the Vatican Window on the World Library of the Future Wales: Book Town The Most Beautiful Book Store in the World Window on Communications Religion Today Film Festival 2018 Theme of World Communications Day 2019 Happy Birthday, Twitter! CALLED TO ETERNAL LIFE 2 forth, rediscovering Pauline prophecy and “TogeTHER WITH YOUNG PEOPLE, renewing its missionary thrust so as to find LET US BRING THE GOSPEL To all” new modes of proclamation and open fron- tiers of every type, both geographical and of his is the theme of thought” (cf. -

Dcco4eln DEMME

DCCO4Eln DEMME ED 033 S2E TE 001 556 MIME Gast, Eavid K. TITLE Minority Americans in Children's Literature. Put Late Jan E7 Ncte 13p. Journal Cit Elementary English; v44 n1 p12-23 Jan 1967 EDRS Price EBBS Price MF-S0.25 HC -$0.75 DescriEtcrs American Indians, *Childrens Eccks, Chinese Americans, Cultural Images, Cultural Traits, Discriminatory Attitudes (Social), Ethnic Groups, *Ethnic Stereotypes, Japanese Americans, Majority Attitudes, *Minority Grcups, Negroes, Racial Discriminaticn, Religious Discrimination, *Social Discrimination, *Scciccultural Patterns, Spanish Americans, Textbook Bias Abstract Children's ficticn written tetimen 1945 and 1962 was analyzed for current stereotypes cf minority Americans, and the results were compared with related studies of adult fiction and school textbocks. Iwo analytic instruments were applied tc 114 incrity characters selected from 42 children's books about American Indians, Chinese, Japanese, Negroes, and Spanish Americans currently living in the United States. In this sampling, virtually no negative stereotypes cf incrity Americans were fcund; the differences in race, creed, and custcms of incrity citizens were fcund tc be dignified far acre than in either adult magazine fiction cr textbcoks; and similarities in bhavicr, attitudes, and values between ajcrity and incrity Americans were emphasized rather than their differences. (Reccmmendations for acticn tc be taken on the basis cf the results, proposals for further experimental study, and a table ranking the verbal stereotypes of the 114 minority American characters are included.) (JE) Tom'oo 556 041101irt 1/I ffEreplirEtttEilifirliii111I ED033928t trrrn aaa za a ate 2M-4 43 2 4IFflikilliffqqq141011Ifiliiiiigu Ph;WIN[Ohl 94iihiPi frOfin111PgI° VIIillIII'riotItiii11 lo;111t01iili;fr irtili@Rigt rit 1 !art la ImeO I.S. -

Exhibitions Photographs Collection

Exhibitions Photographs Collection This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 24, 2015 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Generously supported with funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) Archives and Manuscripts Collections, The Baltimore Museum of Art 10 Art Museum Drive Baltimore, MD, 21032 (443) 573-1778 [email protected] Exhibitions Photographs Collection Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Exhibitions............................................................................................................................................... 7 Museum shop catalog......................................................................................................................... -

Effects of Tourist Investments On

THE EFFECTS OF TOURISM INVESTMENTS ON POVERTY REDUCTION IN RURAL COMMUNITIES IN TANZANIA: THE CASE OF SERENGETI DISTRICT BY RAPHAEL NYAKABAGA MALEYA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RURAL DEVELOPMENT OF SOKOINE UNIVERSITY OF AGRICULTURE. MOROGORO, TANZANIA. 2009 ii ABSTRACT Tanzania is among the few countries in the world endowed with vast range of tourist attractions. The tourism industry is Tanzania’s greatest success story since the introduction of free market economy in 1990s. Despite its impressive recent economic performance, Tanzania remains a poor country. The purpose of this study was therefore to assess the effects of tourism investments on poverty reduction in rural communities in Serengeti district. The specific objectives were to: identify types of tourism investments; examine the effects of tourism investments; and determine the potential tourism development investments. Data were collected from 124 respondents, including 100 community members household heads and 24 key informants using questionnaires, researcher’s diary and checklist. Quantitative data were analysed by using SPSS computer software and “content analysis technique” was used to analyse qualitative data. The study identified different types of tourism investments in rural communities in the study area, their effects on poverty reduction, and potential for tourism investments development. It was concluded that: employment opportunities for rural communities were low in cadres with skills -

Women and Arts : 75 Quotes

WOMEN AND ARTS : 75 QUOTES Compiled by Antoni Gelonch-Viladegut For the Gelonch Viladegut Collection website Paris, March 2011 1 SOMMARY A GLOBAL INTRODUCTION 3 A SHORT HISTORY OF WOMEN’S ARTISTS 5 1. The Ancient and Classic periods 5 2. The Medieval Era 6 3. The Renaissance era 7 4. The Baroque era 9 5. The 18th Century 10 6. The 19th Century 12 7. The 20th Century 14 8. Contemporary artists 17 A GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 19 75 QUOTES: WOMEN AND THE ART 21 ( chronological order) THE QUOTES ORDERED BY TOPICS 30 Art’s Definition 31 The Artist and the artist’s work 34 The work of art and the creation process 35 Function and art’s understanding 37 Art and life 39 Adjectives’ art 41 2 A GLOBAL INTRODUCTION In the professional world we often speak about the "glass ceiling" to indicate a situation of not-representation or under-representation of women regarding the general standards presence in posts or roles of responsibility in the profession. This situation is even more marked in the world of the art generally and in the world of the artists in particular. In the art history women’s are not almost present and in the world of the art’s historians no more. With this panorama, the historian of the art Linda Nochlin, in 1971 published an article, in the magazine “Artnews”, releasing the question: "Why are not there great women artists?" Nochlin throws rejects first of all the presupposition of an absence or a quasi-absence of the women in the art history because of a defect of " artistic genius ", but is not either partisan of the feminist position of an invisibility of the women in the works of art history provoked by a sexist way of the discipline.