Open Merfeldlangston.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C295 Official Journal

Official Journal C 295 of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Information and Notices 7 September 2020 Contents II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2020/C 295/01 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.9572 – BMW/Daimler/Ford/Porsche/Hyundai/Kia/IONITY) (1) . 1 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2020/C 295/02 Euro exchange rates — 4 September 2020 . 2 Court of Auditors 2020/C 295/03 Special Report 16/2020 The European Semester – Country-Specific Recommendations address important issues but need better implementation . 3 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2020/C 295/04 Information communicated by Member States regarding closure of fisheries . 4 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. V Announcements OTHER ACTS European Commission 2020/C 295/05 Publication of an application for approval of amendments, which are not minor, to a product specification pursuant to Article 50(2)(a) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs . 5 2020/C 295/06 Publication of a communication of approval of a standard amendment to a product specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 17(2) and (3) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 . 19 2020/C 295/07 Publication of a communication of approval of a standard amendment to a product specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 17(2) and (3) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 . -

Pierre Bergé Lifts Curtain on Private Library of Rare Books

URL: http://wwd.com/ PAYS: International TYPE: Web Grand Public September 10, 2015 Pierre Bergé Lifts Curtain on Private Library of Rare Books By Miles Socha from WWD issue 09/10/2015 DOWNLOAD PDF Pierre Bergé Dominique Maitre PARIS — Pierre Bergé is no book snob. The former couture boss loves paperbacks, prefers to read on a Kindle when on vacation and devours contemporary novels galore — as he judges several literary prizes in France. This story first appeared in the September 10, 2015 issue of WWD. Subscribe Today. Yet he is equally passionate about his collection of 1,600 rare books, manuscripts and musical scores that he is preparing to auction off , starting Dec. 11 at Drouot in Paris and at six subsequent sales in 2016 and 2017. A selection of about 60 of the 150 initial lots is to go on display at Sotheby’s in New York today through Sunday — providing a glimpse into a highly personal collection amassed over a lifetime. Interviewed in the cozy library on the second floor of his Paris apartment, Bergé said there’s a simple reason why he is parting with tomes that are estimated to sell for as much as $700,000. “Because I’ll be 85 before the end of the year and one has to be conscious of one’s age and think of the future,” he shrugged, seated at the leather-topped table in the center of the room. Proceeds from the auctions, to be conducted in collaboration by Pierre Bergé & Associés, are ultimately destined for the Fondation Pierre Bergé-Yves Saint Laurent , which is to transform into permanent YSL museums in Paris and Morocco in 2017. -

Place Saint-Michel the Place Saint-Michel Is

Place Saint-Michel The Place Saint-Michel is simple – a triangle between two streets, uniform buildings along both, designed by the same architect, a walk of smooth cobblestone. The centerpiece is St. Michael defeating a devil; far above them are four statues symbolizing the four cardinal virtues of prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice. This monument came to be because of the 1848 Revolution and a cholera epidemic in Paris that followed it which killed thousands. This idea of abstract concepts given human form had been popular during the Revolution, the big one, representing the kind of big virtues – like the Four Cardinal Virtues – that everyone could strive for, instead of a single human being whose actions and legacy would turn people against each other. Simultaneous with the creation of Place Saint-Michel, Napoleon III’s renovation brought the Boulevard Saint-Michel into being, and that is the next part of our walk. Facing the fountain with the river at your back, walk on Boulevard Saint-Michel, it’s the street to your left. Walk away from the river along that street. Ultimately, you’ll be turning left on Rue des Écoles, but it’ll be about five minutes to get there, and you can listen to the next track on the way. Boulevard Saint-Michel The character of the street you’re on – wide-open space lined with trees and long, harmonious buildings, plus, often, a view of some landmark in the distance – was a central part of the renovation plan, or the Haussmann plan, as it’s also known. -

Individual Investors Rout Hedge Funds

P2JW028000-5-A00100-17FFFF5178F ***** THURSDAY,JANUARY28, 2021 ~VOL. CCLXXVII NO.22 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 30303.17 g 633.87 2.0% NASDAQ 13270.60 g 2.6% STOXX 600 402.98 g 1.2% 10-YR. TREAS. À 7/32 , yield 1.014% OIL $52.85 À $0.24 GOLD $1,844.90 g $5.80 EURO $1.2114 YEN 104.09 What’s Individual InvestorsRout HedgeFunds Shares of GameStop and 1,641.9% GameStop Thepowerdynamics are than that of DeltaAir Lines News shifting on Wall Street. Indi- Inc. AMC have soared this week Wednesday’stotal dollar vidual investorsare winning While the individuals are trading volume,$28.7B, as investors piled into big—at least fornow—and rel- rejoicing at newfound riches, Business&Finance exceeded the topfive ishing it. the pros arereeling from their momentum trades with companies by market losses.Long-held strategies capitalization. volume rivaling that of giant By Gunjan Banerji, such as evaluatingcompany neye-popping rally in Juliet Chung fundamentals have gone out Ashares of companies tech companies. In many $25billion and Caitlin McCabe thewindowinfavor of mo- that were onceleftfor dead, cases, the froth has been a mentum. War has broken out including GameStop, AMC An eye-popping rally in between professionals losing and BlackBerry, has upended result of individual investors Tesla’s 10-day shares of companies that were billions and the individual in- the natural order between defying hedge funds that have trading average onceleftfor dead including vestorsjeering at them on so- hedge-fund investorsand $24.3 billion GameStopCorp., AMC Enter- cial media. -

Friends of Woodstock Public Library Plants Will Be on Sale Including Kale, Time: 3:00-7:00 P.M

To Register / Para registrarse: Website: www.woodstockpubliclibrary.org Phone: 815.338.0542 In Person: 414 W. Judd St. Woodstock, IL FALL 2018 / SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER = Registration Required Beginning Wednesday, September 5 = Discover what’s new at the Library! BLOOD DRIVE FRIENDS FALL WPL will host Heartland Blood Center. Donated PLANT SALE blood will benefit area hospitals. All donors must FRIENDS OF WOODSTOCK Join the Friends of Woodstock show a photo ID prior to donating. Please sign up for Public Library for their annual an appointment at www.heartlandbc.org or call the PUBLIC LIBRARY Chrysanthemum fundraiser. In library at 815-338-0542. Walk-ins are also welcome. JOIN THE FRIENDS addition to mums, a variety of fall Day/Date: Wednesday/November 28 The Friends of Woodstock Public Library plants will be on sale including kale, Time: 3:00-7:00 p.m. ornamental pepper plants, and is a nonprofit 501(c)3 organization, ornamental grasses. HALF-PRICE FINES WEEK AND dedicated to helping the library. Through annual membership drive and Sale Day/Dates: FOOD DRIVE Monday, September 10 through Sunday, several fundraising events a year the Friday/September 7 Friends actively support the library by 10:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m. September 16, the library will reduce the amount of overdue fines by HALF. Pay only HALF the total funding programs and services, and Saturday/September 8 amount of your overdue fines, lost or damaged providing volunteers for library events. 10:00 a.m.-3:00 p.m. charges, and collection agency fees. The library will Inquire at the library on how you can (or until sold out) waive the remaining charges. -

SAINT-JEAN ACCÈS : ENTRE CHAPELLE S E E U ET TOURBIÈRE Commune De Bertrichamps N Q LES POINTS D’INTÉRÊT RD 590, Direction Raon L’Etape

RANDONNÉES NATURE EN LA TOURBIÈRE DE LA Meurthe Moselle BASSE-ST-JEAN : & UN PAYSAGE LUNAIRE C’est la seule tourbière acide de basse altitude préservée, accessible et valorisée dans le Département de Meurthe-et-Moselle. Comme les tourbières vosgiennes d’altitude voisines, elle offre une végétation exceptionnelle et abrite plusieurs À BERTRICHAMPS libellules remarquables, comme la Cordulie arctique et ses 28 impressionnants yeux verts métalliques, ou l’Agrion de mercure. L’épaisse forêt qui sert d’écrin protecteur à la tourbière favorise la POUR VENIR LE SENTIER DES cohabitation entre plusieurs espèces de pics et divers amphibiens : FACILEMENT FLASHEZ-MOI ! Sonneur à ventre jaune, Salamandre tachetée, Triton. Le petit PICS ET VARIANTE ruisseau aux eaux claires qui alimente la tourbière est peuplé de CONSEIL DÉPARTEMENTAL truites sauvages. Le site est protégé par le Département depuis RANDO54 plus de 10 ans. SAINT-JEAN ACCÈS : ENTRE CHAPELLE S E E U ET TOURBIÈRE Commune de Bertrichamps N Q LES POINTS D’INTÉRÊT RD 590, direction Raon L’Etape. 1ère à gauche à la TIE GI sortie de Bertrichamps. R PÉ AGO Parking : Basse St-Jean. D À VOIR SUR LE PARCOURS : Plus d’infos sur les ENS : Conseil Départemental de Meurthe-et-Moselle nature departement54.fr +33 (0) 3 83 94 56 87 » Les panneaux pédagogiques ENS e-mail : @ - téléphone : (pupitres, bornes de direction sculptées à décalquer : venir avec une feuille et utiliser un crayon, une feuille d’arbre ou LA SPHAIGNE : une craie pour frotter), › » La Tourbière de la Basse Saint Jean, COMME UNE ÉPONGE... unique en Lorraine, Ce sont les sphaignes qui sont » La Chapelle Saint-Jean (13ème siècle), à l’origine des tourbières. -

Concept and Types of Tourism

m Tourism: Concept and Types of Tourism m m 1.1 CONCEPT OF TOURISM Tourism is an ever-expanding service industry with vast growth potential and has therefore become one of the crucial concerns of the not only nations but also of the international community as a whole. Infact, it has come up as a decisive link in gearing up the pace of the socio-economic development world over. It is believed that the word tour in the context of tourism became established in the English language by the eighteen century. On the other hand, according to oxford dictionary, the word tourism first came to light in the English in the nineteen century (1811) from a Greek word 'tomus' meaning a round shaped tool.' Tourism as a phenomenon means the movement of people (both within and across the national borders).Tourism means different things to different people because it is an abstraction of a wide range of consumption activities which demand products and services from a wide range of industries in the economy. In 1905, E. Freuler defined tourism in the modem sense of the world "as a phenomena of modem times based on the increased need for recuperation and change of air, the awakened, and cultivated appreciation of scenic beauty, the pleasure in. and the enjoyment of nature and in particularly brought about by the increasing mingling of various nations and classes of human society, as a result of the development of commerce, industry and trade, and the perfection of the means of transport'.^ Professor Huziker and Krapf of the. -

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism 1 Cover photo: Lancaster Boulevard in Lancaster, California. Source: City of Lancaster. Photo by Tamara Leigh Photography. Street design by Moule & Polyzoides. 25 GREAT IDEAS OF NEW URBANISM Author: Robert Steuteville, CNU Senior Dyer, Victor Dover, Hank Dittmar, Brian Communications Advisor and Public Square Falk, Tom Low, Paul Crabtree, Dan Burden, editor Wesley Marshall, Dhiru Thadani, Howard Blackson, Elizabeth Moule, Emily Talen, CNU staff contributors: Benjamin Crowther, Andres Duany, Sandy Sorlien, Norman Program Fellow; Mallory Baches, Program Garrick, Marcy McInelly, Shelley Poticha, Coordinator; Moira Albanese, Program Christopher Coes, Jennifer Hurley, Bill Assistant; Luke Miller, Project Assistant; Lisa Lennertz, Susan Henderson, David Dixon, Schamess, Communications Manager Doug Farr, Jessica Millman, Daniel Solomon, Murphy Antoine, Peter Park, Patrick Kennedy The 25 great idea interviews were published as articles on Public Square: A CNU The Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) Journal, and edited for this book. See www. helps create vibrant and walkable cities, towns, cnu.org/publicsquare/category/great-ideas and neighborhoods where people have diverse choices for how they live, work, shop, and get Interviewees: Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Jeff around. People want to live in well-designed Speck, Dan Parolek, Karen Parolek, Paddy places that are unique and authentic. CNU’s Steinschneider, Donald Shoup, Jeffrey Tumlin, mission is to help build those places. John Anderson, Eric Kronberg, Marianne Cusato, Bruce Tolar, Charles Marohn, Joe Public Square: A CNU Journal is a Minicozzi, Mike Lydon, Tony Garcia, Seth publication dedicated to illuminating and Harry, Robert Gibbs, Ellen Dunham-Jones, cultivating best practices in urbanism in the Galina Tachieva, Stefanos Polyzoides, John US and beyond. -

The Infected Republic: Damaged Masculinity in French Political Journalism, 1934-1938

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 2010 The Infected Republic: Damaged Masculinity in French Political Journalism, 1934-1938 Emily C. Ringler Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Ringler, Emily C., "The Infected Republic: Damaged Masculinity in French Political Journalism, 1934-1938" (2010). Honors Papers. 392. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/392 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Infected Republic: Damaged Masculinity in French Political Journalism 1934-1938 Emily Ringler Submitted for Honors in the Department of History April 30, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter I: Constructing and Dismantling Ideals of French Masculinity in the Third Republic 10 Man and Republic: the Gendering of Citizenship 10 Deviance and Degenerates in the Third Republic 14 The Dreyfus Affair and Schisms in Ideals of Masculinity 22 Dystopia and Elusive Utopia: Masculinity and Les Années Folles 24 Political Instability and Sexual Symbolism in the 1930s 29 Chapter II: The Threat of the Other: Representations of Damaged Masculinity on the Right 31 Defining the Right Through Its Uses of Masculinity 31 Images of the Other 33 The Foreign Other as the -

Multnomah County Library Collection Shrinkage—A Baseline Report

Y T N U MULTNOMAH COUNTY LIBRARY COLLECTION SHRINKAGE—A O BASELINE REPORT H NOVEMBER 2006 A REPORT FOR THE ULTNOMAH OUNTY IBRARY M A M C L O REPORT #009-06 N T L REPORT PREPARED BY: ATT ICE RINCIPAL NALYST U M N , P A BUDGET OFFICE EVALUATION MULTNOMAH COUNTY, OREGON 503-988-3364 http://www.co.multnomah.or.us/dbcs/budget/performance/ MULTNOMAH COUNTY LIBRARY COLLECTION SHRINKAGE—A BASELINE REPORT Executive Summary In July 2005, the library administration contacted staff from the Multnomah County Budget Office Evaluation, a unit external to the Library’s internal management system, to request independent assistance estimating the amount of missing materials at the library, known in the private sector as ‘shrinkage’. While much of shrinkage can be due to theft, it is impossible to distinguish between this and misplaced or inaccurate material accounting. Results reported herein should be considered a baseline assessment and not an annualized rate. There are three general ways to categories how shrinkage occurs to the library collection: materials are borrowed by patrons and unreturned; items which cannot be located are subsequently placed on missing status; and materials missing in the inventory, where the catalog identifies them as being on the shelf, are not located after repeated searches. Each of these three ways was assessed and reported separately due to the nature of their tracking. Shrinkage was measured for all branches and outreach services and for most material types, with the exception of non-circulating reference materials, paperbacks, CD-ROMS, maps, and the special collections. This analysis reflected 1.67 million of the 2.06 million item multi-branch collection (87% of the entire collection). -

News Updates Please Email To

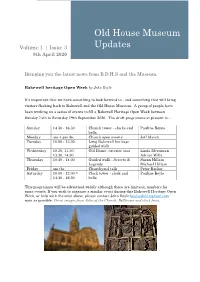

Old House Museum Volume 1 | Issue 3 Updates 9th April 2020 Bringing you the latest news from B.D.H.S and the Museum. Bakewell heritage Open Week by John Boyle It's important that we have something to look forward to - and something that will bring visitors flocking back to Bakewell and the Old House Museum. A group of people have been working on a series of events to fill a Bakewell Heritage Open Week between Sunday 13th to Saturday 19th September 2020. The draft programme at present is: - Sunday 14.30 - 16.30 Church tower - clocks and Pauline Boyne bells Monday am + pm tbc Church open events Jeff Marsh Tuesday 10.00 - 13.00 Long Bakewell heritage guided walk Wednesday 10.30, 11.30, Old House, exterior tour Linda Merriman 13.30, 14.30 Adrian Wills Thursday 10.30 - 14.00 Guided walk - Secrets & Susan Hillam Legends Michael Hillam Friday am tbc Churchyard talk Peter Barker Saturday 10.00 - 12.00 = Clock tower - clock and Pauline Boyle 14.30 - 16.30 bells This programme will be advertised widely although there are limits on numbers for some events. If you wish to organise a similar event during this Bakewell Heritage Open Week, or help with the ones above, please contact John Boyle [email protected] soon as possible. Great images from John of the Church, Bellframe and clock front. 2 Clock front Susan Hillam leads 'Secrets & Legends" Bakewell businesses project - from George Challenger Members might like to improve the project described below by adding or correcting information on shops and businesses to the tables I have prepared. -

Volume 21-#81 December 1999 BELGIAN LACES ISSN 1046-0462

Belgian Laces PHILIPPE AND MATHILDE: BELGIANS CELEBRATE THE ENGAGEMENT November 13th, 1999 Prince Philippe and Mademoiselle Mathilde d'Udekem d'Acoz. Occasion for which, besides Belgians from all ten provinces, the Royal Palace and the King Baudouin Foundation had taken the time to invite and include "ordinary" citizen from the Belgian communities abroad with the help of "Union francophone des Belges à l'étranger" (UFBE) and "Vlamingen in de Wereld" (VIW). For more on the subject check the internet site: http://www.mathilde-philippe.net Volume 21-#81 December 1999 BELGIAN LACES ISSN 1046-0462 Official Quarterly Bulletin of THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Belgian American Heritage Association Founded in 1976 Our principal objective is: Keep the Belgian Heritage alive in our hearts and in the hearts of our posterity President/Newsletter editor Régine Brindle Vice-President Gail Lindsey Treasurer/Secretary Melanie Brindle Past Presidents Micheline Gaudette, founder Pierre Inghels Deadline for submission of Articles to Belgian Laces: January 31 - April 30 - July 31 - October 31 Send payments and articles to this office: THE BELGIAN RESEARCHERS Régine Brindle 495 East 5th Street Peru IN 46970 Tel:765-473-5667 e-mail [email protected] *All subscriptions are for the calendar year* *New subscribers receive the four issues of the current year, regardless when paid* TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Editor - Membership p73 Instructions from the Ohio Valley to French Emigrants, from Indiana Magazine of History p74 Belgian Families on the 1850 Perry Co., IN US Census, by Don GOFFINET p78 Declarations of Intention - Brown Co. WI, by Mary Ann DEFNET p79 How Hobby and Heritage Cross paths, by Linda SCONZERT-NORTON p80 Nethen Marriage Index 1800-1870, by Régine BRINDLE p82 Belgian Reunion, 1930, by Donna MARTINEZ p83 1900 Bates Co.