Dcco4eln DEMME

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Merfeldlangston.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of French and Francophone Studies THE VILLAGES DU LIVRE: LOCAL IDENTITY, CULTURAL POLITICS, AND PRINT CULTURE IN CONTEMPORARY FRANCE A Thesis in French by Audra Lynn Merfeld-Langston © 2007 Audra Lynn Merfeld-Langston Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2007 The thesis of Audra Lynn Merfeld-Langston was reviewed and approved* by the following: Willa Z. Silverman Associate Professor of French and Francophone Studies and Jewish Studies Thesis Advisor Chair of Committee Thomas A. Hale Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of African, French, and Comparative Literature Head of the Department of French and Francophone Studies Greg Eghigian Associate Professor of Modern European History Jennifer Boittin Assistant Professor of French, Francophone Studies and History and Josephine Berry Weiss Early Career Professor in the Humanities *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Over the past several decades, the cultural phenomenon of the villages du livre has exploded throughout the Hexagon. Taking their cue from the original book town, Hay-on-Wye, in Wales, rural French communities once in danger of disappearing have reclaimed their economic future and their heritage. Founded in 1961, Hay-on-Wye has served as a model for other towns to establish a used book trade, organize literary festivals, and promote the practice of traditional book arts that include calligraphy, binding, paper-making, and printing. In the French villages du livre of Bécherel (Bretagne), Montolieu (Languedoc), Fontenoy-la-Joûte (Lorraine), Montmorillon (Poitou-Charentes), and La Charité-sur-Loire (Bourgogne), ancillary enterprises such as museums, bookstores, cafés, and small hotels now occupy buildings that had stood vacant for years. -

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism 1 Cover photo: Lancaster Boulevard in Lancaster, California. Source: City of Lancaster. Photo by Tamara Leigh Photography. Street design by Moule & Polyzoides. 25 GREAT IDEAS OF NEW URBANISM Author: Robert Steuteville, CNU Senior Dyer, Victor Dover, Hank Dittmar, Brian Communications Advisor and Public Square Falk, Tom Low, Paul Crabtree, Dan Burden, editor Wesley Marshall, Dhiru Thadani, Howard Blackson, Elizabeth Moule, Emily Talen, CNU staff contributors: Benjamin Crowther, Andres Duany, Sandy Sorlien, Norman Program Fellow; Mallory Baches, Program Garrick, Marcy McInelly, Shelley Poticha, Coordinator; Moira Albanese, Program Christopher Coes, Jennifer Hurley, Bill Assistant; Luke Miller, Project Assistant; Lisa Lennertz, Susan Henderson, David Dixon, Schamess, Communications Manager Doug Farr, Jessica Millman, Daniel Solomon, Murphy Antoine, Peter Park, Patrick Kennedy The 25 great idea interviews were published as articles on Public Square: A CNU The Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) Journal, and edited for this book. See www. helps create vibrant and walkable cities, towns, cnu.org/publicsquare/category/great-ideas and neighborhoods where people have diverse choices for how they live, work, shop, and get Interviewees: Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Jeff around. People want to live in well-designed Speck, Dan Parolek, Karen Parolek, Paddy places that are unique and authentic. CNU’s Steinschneider, Donald Shoup, Jeffrey Tumlin, mission is to help build those places. John Anderson, Eric Kronberg, Marianne Cusato, Bruce Tolar, Charles Marohn, Joe Public Square: A CNU Journal is a Minicozzi, Mike Lydon, Tony Garcia, Seth publication dedicated to illuminating and Harry, Robert Gibbs, Ellen Dunham-Jones, cultivating best practices in urbanism in the Galina Tachieva, Stefanos Polyzoides, John US and beyond. -

News Updates Please Email To

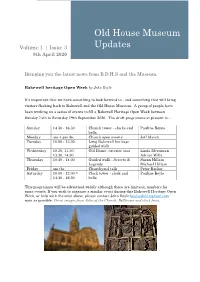

Old House Museum Volume 1 | Issue 3 Updates 9th April 2020 Bringing you the latest news from B.D.H.S and the Museum. Bakewell heritage Open Week by John Boyle It's important that we have something to look forward to - and something that will bring visitors flocking back to Bakewell and the Old House Museum. A group of people have been working on a series of events to fill a Bakewell Heritage Open Week between Sunday 13th to Saturday 19th September 2020. The draft programme at present is: - Sunday 14.30 - 16.30 Church tower - clocks and Pauline Boyne bells Monday am + pm tbc Church open events Jeff Marsh Tuesday 10.00 - 13.00 Long Bakewell heritage guided walk Wednesday 10.30, 11.30, Old House, exterior tour Linda Merriman 13.30, 14.30 Adrian Wills Thursday 10.30 - 14.00 Guided walk - Secrets & Susan Hillam Legends Michael Hillam Friday am tbc Churchyard talk Peter Barker Saturday 10.00 - 12.00 = Clock tower - clock and Pauline Boyle 14.30 - 16.30 bells This programme will be advertised widely although there are limits on numbers for some events. If you wish to organise a similar event during this Bakewell Heritage Open Week, or help with the ones above, please contact John Boyle [email protected] soon as possible. Great images from John of the Church, Bellframe and clock front. 2 Clock front Susan Hillam leads 'Secrets & Legends" Bakewell businesses project - from George Challenger Members might like to improve the project described below by adding or correcting information on shops and businesses to the tables I have prepared. -

Listen to the Voice of God in the Voice of Youth Because They Will Tell Us What They Expect of the Church

Year XI - n. 57 August–October 2018 Figlie di San Paolo - Casa generalizia Via San Giovanni Eudes, 25 - 00163 Roma [email protected] - www.paoline.org Listen to the voice of God in the voice of youth because they will tell us what they expect of the Church. Bishop Raúl Biord Castillo of La Guaira, Venezuela Foto: Štěpán Rek Summary DEAREST SISTERS... PAULINE PANORAMA The Circumscriptions Italy: Inauguration of Regina Apostolorum Hospital’s Multi-Purpose Hall Celebrating the Sunday of the Word in Prison Bolivia: International Book Fair Congo: Inauguration of an FSP Apostolic Center in Matadi Germany: Frankfurt Book Fair Great Britain: Ecumenical Award Pakistan: “Jesus calls you to serve” Peru: Recounting the Bible to Children Philippines: Cardinal Sin Catholic Book Awards Romania: 25 Years of Pauline Presence Our studies Pastoral Communication Through Films Bridging the Digital Divide in Nigeria THE SYNOD ON YOUNG PEOPLE Synod in Full Swing MOVING Ahead WITH Thecla Woman Associated to Priestly Zeal SHARING OUR STORIES My Vocation AGORÀ OF Communications Virtual and Real: An Anthropological Change? Calendar of the General Government THE PAULINE FAMILY Korea: 1st Formation Course on the Charism of the Pauline Family Italy: 22nd Course on the Pauline Charism Italy: Good Shepherd Sisters: 80th Anniversary of Foundation IN THE SPOTLIGHT Window on the Church Sacred Music: 18th Edition of Anima Mundi Digitization of the World’s Oldest Library Peace Journalism Takes Center Stage in the Vatican Window on the World Library of the Future Wales: Book Town The Most Beautiful Book Store in the World Window on Communications Religion Today Film Festival 2018 Theme of World Communications Day 2019 Happy Birthday, Twitter! CALLED TO ETERNAL LIFE 2 forth, rediscovering Pauline prophecy and “TogeTHER WITH YOUNG PEOPLE, renewing its missionary thrust so as to find LET US BRING THE GOSPEL To all” new modes of proclamation and open fron- tiers of every type, both geographical and of his is the theme of thought” (cf. -

Books in Book Towns

Regenerating Regional Culture: A Study of the International Book Town Movement Jane Elizabeth Frank BA (Hons) The University of Queensland MBus (Arts Mgt) Queensland University of Technology School of Humanities Arts, Education and Law Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 Declaration This work has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the thesis itself. Jane Frank September 2015 ii Abstract This thesis explores the international Book Town Movement that, from its beginnings in the small Welsh market town of Hay-on-Wye in the early 1960s, has escalated to incorporate more than 50 villages and towns in 27 countries. This phenomenon has enabled peripheral communities in Europe and across the globe to reclaim their economic futures and impact on the cultural sphere as increasingly powerful sites and sources of creativity. This study seeks to understand the reasons for this renaissance of interest in the preservation of traditional print culture in the countryside at a point in history when the book publishing industry is in a state of flux as it adapts to new digital technologies and globalisation of markets, leading to a clarification of the relationship between new books and the second-hand book economy. At the centre of this investigation is an acknowledgement of the book as a unique item of cultural consumption and a catalyst in book town creation – at once a remarkable artefact and a springboard for contemporary cultural debate. -

THE CAMBRIDGE History of the Book in Britain Volume VII the Twentieth Century and Beyond Edited by ANDREW NASH CLAIRE SQUIRES A

This chapter has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form, subsequent to appropriate editorial input by Cambridge University Press, in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain: Volume VII The Twentieth Century and Beyond. THE CAMBRIDGE History of the Book in Britain Volume VII The Twentieth Century and Beyond Edited by ANDREW NASH CLAIRE SQUIRES And IAN WILLISON 30 Book events, book environments DAVID FINKELSTEIN AND CLAIRE SQUIRES Since the Second World War, a common conception has been that the literary festival has become one of the key sites for the promotion of books and literary culture in the UK. As currently conceived by the myriad of festivals worldwide dedicated to celebrating literary culture and the book, the literary festival conjoins the commercial aspects found in trade book fairs around the world (selling books, exhibiting new titles, offering space for trade representatives to meet) with the promotion of new and established writers through public readings, book signings and encounters with readers. The literary festival has become a major fixture on the publishing circuit, utilised to showcase new works by established authors and provide high visibility and marketing opportunities for publishers. The first multi-sessional literary festival of this sort in Britain was launched in Cheltenham in 1949.1 In the post-war period, and particularly after 1970, the development of the literary festival continued, to the extent that by 2015, the number of literary and literature-related festivals in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales had risen exponentially to over 217.2 This growth, which is explored later in this chapter, attests to the values (social, cultural and financial) of such events to local economies and communities. -

Creative Scotland

Literature and Publishing Sector Review June 2015 By: Nordicity in association with Drew Wylie For: Creative Scotland Literature and Publishing Sector Review Final Report June 2015 Commissioned by: Creative Scotland Prepared by: in association with Table of Contents FOREWORD 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. SECTOR REVIEW CONTEXT 15 2. RE-SCOPING THE SECTOR 18 3. SCOTLAND’S WRITERS 20 4. DEVELOPING A NATION OF READERS 43 5. PUBLISHING IN SCOTLAND 52 6. THE SECTOR ECOSYSTEM 76 7. INTERNATIONAL PROMOTION AND MARKET DEVELOPMENT 95 8. BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER 111 No title Lists 113 Conclusions 113 Recommendations 116 Figures 119 Tables 120 i Literature and Publishing Sector Review FOREWORD The Literature and Publishing Sector Review is the fifth Sector Review undertaken by Creative Scotland. It follows Reviews for Theatre, Dance, Music and Film, while Reviews for Visual Arts, Creative Learning and Equalities, Diversity and Inclusion will also be published this year. Once complete, the Sector Reviews will form the basis from which we will develop a broader Arts Strategy, a strategy that will sit alongside those for Screen, Creative Industries and International, all of which underpin the delivery of Creative Scotland’s 10 Year Plan, Unlocking Potential, Embracing Ambition. The Arts Strategy will provide a national overview of the arts in contemporary Scotland - highlighting opportunities, challenges, connections and the role of the arts in society. It will set out a shared action plan that will contribute to the long-term health of the arts, including the support needed for individual artists to thrive here. It will be a strategy rooted in, and of, Scotland’s people and places. -

1 Issue Briefing Book

ISSUE BRIEFING BOOK: 1 WHAT’s InsIDE? Introduction ..............................................................................................................................4 Emerging Issues: Public Health ..............................................................................................6 Connecticut Must Address the Structural Issues Causing Disproportionate Harm to the Health of Communities of Color .........................................................................................................7 Family Economic Security: Housing .....................................................................................13 Part 1: Investing in Affordable Housing will Improve the Economic Stability and Well-Being of Connecticut Residents ......................................................................................................14 Part 2: Connecticut’s Eviction Crisis Predates the COVID-19 Pandemic, and it will Only Intensify in the Pandemic’s Aftermath Unless the State Acts ................................................18 Family Economic Security: Justice ........................................................................................22 Part 1: Give Me Liberty - The Rising Toll of COVID-19 on Connecticut’s Incarcerated Populations and why Decarceration must be part of the Solution .........................................23 Part 2: Keeping Undocumented Families in Connecticut Healthy, Safe, Connected, and Together during the COVID-19 Pandemic ............................................................................30 -

Planning History

PLANNING HISTORY BULLETIN OF THE INTlERNATIONAL PLANNING HISTORY SOCIETY VOL. 19 NO. 2/ 3 • 1997 llSSN 0959-5005 PlLANNKNG HKSTORY PlLANNJIN"G HJIS'fORY BULIEfII ' OF THE n ITEPJ IAnOllAt fLAt n m IG HISTOP:{ srJ":IETI BULlETIN OF TIlE DITERNATIONAL PLANNING HISTORY SOCIETY EDITOR Or Pieter Uyttenhove CONTENTS 64 rue des Moines Or Peter J. larkham P·?5017 Birmingham School of Planning Paris University of Central England France Perry BaIT Birmingham Professor Shun·jchi Watanabe 8422SU Science University of Tokyo UK Yamazaki , Noda-shi Chiba-ken 278 rei: 0121 331 5145 / Fax: 0121 356 9915 Japan E-mail: [email protected] rei: 81 47424 1501 I Fax: 81 471 25 7833 Professor Stephen V. Ward EDITOP.IAL page 2 EDITORIAL BOARD School of Planning Oxford Srookes University Il000eRS page 3 Or Gerhard Fehl Headington Lehrstuhl filr Planungstheorie Oxford AP..11CI P3 Technische Hochschule Aachen OX! 4LR 5100 Aachen UK Central London in the 1950s: comprehensive schemes Schinkelstrasse 1 Tel: 01865 483421 I Fax: 01865 483559 south of the Thames Germany Emmallue/ V. Marmams page 12 Tel: 0241 805029 / Fax: 02418888137 Professor Michael Ebner Department of History Town planning and conservationist policies in Or Kiki Kafkoula Lake Forest College Department of Urban and Regional Planning 555 North Sheridan Road the historic city centre of Barcelona (1860-1930) School of Architecture Lake Forest, IL 60045-2399 loall Ganau page 23 Aristotle University of Thessalonika USA Thessalonika 54006 Tel: 7087355135 / Fax: 708 735 6291 Landscape, neighbourhood m,d accessibility: Greece the contributions of Margaret Feilman to planning Tel: 3031 995495 / Fax: 3031 995576 and development in Western Australia 8arrie Melotte page 32 Professor Georgia Piccinato Published by the School of Planning, Faculty of the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia Vladimir Semyonov and the first Russian Built Environment, UCE on behalf of the International Oipartimento di Urbanistica 'garden town' near Moscow 30125 Venezia Santa Croce 1957 Planning History Society. -

Agenzia Servizi Editoriali RIGHTS LIST FRANKFURT BOOK FAIR

Agenzia Servizi Editoriali RIGHTS LIST FRANKFURT BOOK FAIR 2011 FICTION Literary Fiction, Crimes, Historical Novels & Memoirs Agenzia Servizi Editoriali Anna Spadolini, Guido Lagomarsino Via Adelaide Bono Cairoli 37 | 20127 Milano | Italy Tel +39 02 28510504 | +39 02 87393515 email: [email protected] | www.serv-ed.it WORLD TRANSLATION RIGHTS ON BEHALF OF: Derive Approdi (Roma, Italy), p. 3 Ediciclo (Portogruaro, Italy), p. 6 Il Melangolo (Genova, Italy), p. Libros del Zorzal (Buenos Aires, Argentina), p. Magenes editorial (Milano, Italy), p. Manni editori (Lecce, Italy), p. Stampa Alternativa (Viterbo,Italy), p. 3 DERIVE APPRODI Translation rights: Agenzia Servizi Editoriali Various Authors LA FUGA DAL CARCERE Storia, teoria e pratica (Escaping from Prison. History, Theory and Practice) DeriveApprodi p. 192 - € 16.00 This book includes exciting and entertaining stories about people who tried to escape from prison - one of the most recurrent and classic literary topics of any time - very famous stories that inspired poets, novelists, screenwriters and film directors, along with equally extraordinary escapes that remained almost unknown. In addition to the stories and chronicles, the book also collects eyewitness accounts narrated by the protagonists of some prison escapes and includes a significant repertoire of images on the theme. Barbara Balzerani CRONACA DI UN’ATTESA (Diary of a wait) memoir DeriveApprodi 2011 p. 128 - € 13.00 Cronaca di un’attesa is the story of the last year the author spent on parole before the end of sentence. When you can begin to count months, and after decades of hiding and jail, you can finally change the look and perspective. It is like living a suspended time of an eve on the threshold of a doorway that opens onto an unknown, inviting and elusive landscape. -

CLOCK TOWER BOOKS, 5 Market Street, Hay on Wye, Les Barrett : Good Quality General Books, Rare and Classic Hereford HR3 5AF

1. THE CHILDREN’S BOOKSHOP. Toll Cottage, Pontvaen, 3. THE OLD ELECTRIC SHOP. 10 Broad Street, Hay-on- 7. TANGLED PARROT @ Eighteen Rabbit. 2 Lion St, Hay, 12. HAY-ON-WYE BOOKSELLERS. 13/14 High Town, Hay-on-Wye, HR3 5EW. Tel: (01497) 821083. Wye, HR3 5DB. Tel: 01497 821194 HR3 5AA. 01497 822882 HR3 5AA. Selection of new and used Hay-on-Wye, Hereford. Tel: (01497) 820875. Just outside Hay on Wye on the Clifford road, a few hundred Email: [email protected] A shop of marvellous music books alongside a selection of new and second hand vinyl www.hayonwyebooksellers.com Quality secondhand and things of interest, both new and vintage, with ever-changing and CD’s. Email: [email protected] yards beyond the Co-op supermarket. We have a large and antiquarian books - suit scholars, collectors and light-hearted varied stock, covering all aspects of children’s literature. On- furniture, homewares, books, clothes and gifts. Within, we www.tangledparrot.com site parking. Books bought (phone first, if possible). Open have a fantastic fully-licensed vegetarian café with inventive, bookworms. We also offer a varied selection of new books at half- 8. MURDER AND MAYHEM. 5 Lion St, Hay-on-Wye, price or less. Large clearance section. Browsers welcome. 9.30-5.30 Mon-Sat. Email: [email protected]. modern food created daily, excellent coffee and indulgent Hereford, HR3 5AA. Tel: (01497) 821613. Walk or stalk Web: www.childrensbookshop.com freshly-made cakes. Open 10am-5pm, every day. We are always interested in buying libraries or small collections. -

Superstores and the Evolution of Firm Capabilities in American Bookselling Daniel M.G

Strategic Management Journal Strat. Mgmt. J., 21: 1043–1059 (2000) SUPERSTORES AND THE EVOLUTION OF FIRM CAPABILITIES IN AMERICAN BOOKSELLING DANIEL M.G. RAFF* The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A. and National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. This study considers the transformation of book retailing in America ca. 1970–95. The major transition was less modal sales venues shifting from Central Business Districts to suburban locations than the rise of extremely broadly merchandised ‘superstores’ and their supporting infrastructure. The paper documents two superficially similar but from a capabilities perspective quite different superstore business models, one identified with Borders and the other with Barnes & Noble. The two companies’ key capabilities originated and developed in distinctive ways, one oriented around the management of information and the other around scale. Complementarities and the persistence of core capabilities are striking features of the organi- zational histories, but so is—over a fairly extended period—evolutionary change. Copyright 2000 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. INTRODUCTION force in retail bookselling. This proceeded in two phases. During the first, the stores of the chain Our images of the colonial America usually companies were of roughly the same size as those involve a relatively primitive economy with rela- of the independents. The principal nonorgani- tively low levels of per capita income, no facto- zational difference between the two was ries and generally low levels of technology in locational: the independents were predominantly the cities and towns, and much of the population sited in central business districts and the shopping engaged, in isolated places and for long and streets of towns, while the chain stores were terribly demanding hours, in agriculture.