Women and Arts : 75 Quotes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 1998-1999 JUSTIN GUARIGLIA Children Along the Streets of Jakarta, Indonesia, Welcome President and Mrs

M E S S A G E F R O M J I M M Y C A R T E R ANNUAL REPORT 1998-1999 JUSTIN GUARIGLIA Children along the streets of Jakarta, Indonesia, welcome President and Mrs. Carter. WAGING PEACE ★ FIGHTING DISEASE ★ BUILDING HOPE The Carter Center One Copenhill Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5100 Fax (404) 420-5145 www.cartercenter.org THE CARTER CENTER A B O U T T H E C A R T E R C E N T E R C A R T E R C E N T E R B O A R D O F T R U S T E E S T H E C A R T E R C E N T E R M I S S I O N S T A T E M E N T Located in Atlanta, The Carter Center is governed by its board of trustees. Chaired by President Carter, with Mrs. Carter as vice chair, the board The Carter Center oversees the Center’s assets and property, and promotes its objectives and goals. Members include: The Carter Center, in partnership with Emory University, is guided by a fundamental houses offices for Jimmy and Rosalynn commitment to human rights and the alleviation of human suffering; it seeks to prevent and Jimmy Carter Robert G. Edge Kent C. “Oz” Nelson Carter and most of Chair Partner Retired Chair and CEO resolve conflicts, enhance freedom and democracy, and improve health. the Center’s program Alston & Bird United Parcel Service of America staff, who promote Rosalynn Carter peace and advance Vice Chair Jane Fonda Charles B. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

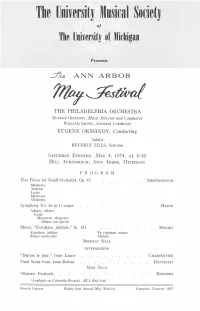

The Uuiversitj Musical Souietj of the University of Michigan

The UuiversitJ Musical SouietJ of The University of Michigan Presents ANN ARBOR THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA E UGENE ORMANDY , Music Director and Conduct01' WILLIAM SMITH, Assistant Conductor EUGENE ORMANDY, Conducting Soloist BEVERLY SILLS, Soprano SATURDAY EVENING , MAY 4, 1974, AT 8 :30 HILL AUDITORIUM , ANN ARBOR , MICHIGAN PROGRAM Five Pieces for Small Orchestra, Op. 42 SHOSTAKOVI CH Moderato Andante Largo Moderato Allegretto Symphony No. 88 in G major HAYDN Adagio; allegro La rgo Menuetto : a llegretto Allegro con spirito Motet, "Exsultate, jubilate," K. 165 MOZART Exsul tate, jubilate Tu virginum corona Fulge t arnica di es .-\lIelu ja BEVERL Y S ILLS IN TERiVIISSION " Depuis Ie jour," fr om Louise CHARPENTIER Fin al Scene from Anna Bolena DON IZETTl MISS SILLS ';'Roman Festivals R ESPIGHI *A vailable on Columbia R ecords RCA R ed Seal F ourth Concert Eighty-first Annua l May Festi n ll Complete Conce rts 3885 PROGRAM NOTES by G LENN D. MCGEOCH Five Pieces for Small Orchestra, Op. 42 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906- ) The Fi ve Pieces, written by Shostakovich at the age of twenty-nine, were never mentioned or listed among his major works, until Ivan M artynov, in a monograph ( 1947) referred to them as "Five Fragments for Orchestra, 193 5 manuscript, op. 42." A conflict, which had begun to appear between the compose r's natura l, but advanced expression, and the Soviet official sanction came to a climax in 1934 wh en he produced his "avant guarde" opera Lady Ma cbeth of Mzensk. He was accuse d of "deliberate musical affectation " and of writing "un Soviet, eccent ric music, founded upon formalistic ideas of bourge ois musical conce ptions." Responding to this official castigation, he wrote a se ries of short, neoclassic, understated works, typical of the Fi ve Pieces on tonight's program. -

Henrietta Shore in Point Lobos and Carmel

HENRIETTA SHORE IN POINT LOBOS AND CARMEL: SPIRIT OF PLACE, ESSENCE OF BEING by MINA TOCHEVA STOEVA (Under the Direction of Janice Simon) ABSTRACT Shore’s visual vocabulary developed from Impressionism towards more stylized, abstracted forms in her 1920s work, and after 1930 culminated in the textured, detailed and almost tactile drawings produced in Carmel, California. This thesis focuses on the impact that Carmel had on her personal and artistic life. A detailed analysis of Shore’s images of the Monterey Peninsula establishes the connection between her extended visual narrative of the locale and the tradition of written ecocentric narratives. I will consider the Theosophical and transcendental ideas that Shore expressed in her work and relate them to Lawrence Buell’s theory of ecocentric narrative. By unveiling the subtleties of such a narrative and the process of its creation, the present analysis will further our understanding of Shore’s deeply emotional and spiritual attachment to the Monterey Peninsula. More than merely depicting a peculiar landscape, Shore’s late drawings reveal her preoccupation with current literary and philosophical trends, while simultaneously creating an intimate reflection of the artist’s self. INDEX WORDS: Henrietta Shore (1880-1962), Carmel, Point Lobos, landscape, transcendentalism, Ralph Waldo Emerson, place, ecocentric narrative, Theosophy, self-portrait, American modernism, Johann Wolfgang Goethe HENRIETTA SHORE IN POINT LOBOS AND CARMEL: SPIRIT OF PLACE, ESSENCE OF BEING by MINA TOCHEVA STOEVA BA, -

Prefaces to Scalia/Ginsburg: a (Gentle) Parody of Operatic Proportions

WANG, SCALIA/GINSBURG: A (GENTLE) PARODY OF OPERATIC PROPORTIONS, 38 COLUM. J.L. & ARTS 237 (2015) Prefaces to Scalia/Ginsburg: A (Gentle) Parody of Operatic Proportions Preface by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Scalia/Ginsburg is for me a dream come true. If I could choose the talent I would most like to have, it would be a glorious voice. I would be a great diva, perhaps Renata Tebaldi or Beverly Sills or, in the mezzo range, Marilyn Horne. But my grade school music teacher, with brutal honesty, rated me a sparrow, not a robin. I was told to mouth the words, never to sing them. Even so, I grew up with a passion for opera, though I sing only in the shower, and in my dreams. One fine day, a young composer, librettist and pianist named Derrick Wang approached Justice Scalia and me with a request. While studying Constitutional Law at the University of Maryland Law School, Wang had an operatic idea. The different perspectives of Justices Scalia and Ginsburg on constitutional interpretation, he thought, could be portrayed in song. Wang put his idea to the “will it write” test. He composed a comic opera with an important message brought out in the final duet, “We are different, we are one”—one in our reverence for the Constitution, the U.S. judiciary and the Court on which we serve. Would we listen to some excerpts from the opera, Wang asked, and then tell him whether we thought his work worthy of pursuit and performance? Good readers, as you leaf through the libretto, check some of the many footnotes disclosing Wang’s sources, and imagine me a dazzling diva, I think you will understand why, in answer to Wang’s question, I just said “Yes.” Preface by Justice Antonin Scalia: While Justice Ginsburg is confident that she has achieved her highest and best use as a Supreme Justice, I, alas, have the nagging doubt that I could have been a contendah—for a divus, or whatever a male diva is called. -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

Marzo - Aprile 2021 PROGRAMMA DELLE PROPOSTE CULTURALI Marzo - Aprile 2021 RIEPILOGO DELLE PROPOSTE CULTURALI

marzo - aprile 2021 PROGRAMMA DELLE PROPOSTE CULTURALI marzo - aprile 2021 RIEPILOGO DELLE PROPOSTE CULTURALI CONFERENZE - PRESENTAZIONI 2 marzo Artisti/collezionisti tra Cinquecento e Settecento 9 marzo Le donne nell’architettura tra XX e XXI secolo 16 marzo Dante fra arte e poesia 23 marzo La rivincita delle artiste nella pittura del ‘600 - parte II 30 marzo Il “mio”Arturo 6 aprile Arte al tempo di Dante: “Ora ha Giotto il grido!” 20 aprile La lettera di Raffaello a Leone X: nasce la moderna concezione di conservazione dei beni culturali PALAZZI, MUSEI E SITI ARTISTICO/ARCHITETTONICI 11 marzo Il Cimitero Monumentale VISITE A CHIESE 4 marzo Santa Maria Beltrade: Deco’, ma non si direbbe 15 marzo San Marco 24 marzo Chiesa e museo di San Fedele 26 aprile San Francesco al Fopponino VISITE A MOSTRE 10 marzo “Tiepolo. Venezia, Milano, l’Europa” alle Gallerie d’Italia 31 marzo Carla Accardi, una donna come tante, al Museo del ‘900 7 aprile Robot al Mudec: scienza, tecnica, arte, antropologia 14 aprile “Tiepolo. Venezia, Milano, l’Europa” alle Gallerie d’Italia 16 aprile Le Signore del Barocco a Palazzo Reale in copertina: Domenico di Michelino, affresco, 1465, cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore - Firenze 2 ITINERARI D’ARTE 18 marzo Dal teatro Dal Verme alla chiesa di Santa Maria alla Porta 22 marzo Una passeggiata lungo le mura spagnole 29 marzo I segreti della Via Moscova e dintorni 12 aprile Nuovi Arrivi tra Piazza Liberty/Piazza Cordusio/via Brisa: la città che cambia 13 aprile Dal Carrobbio alla Darsena, le porte “Ticinesi” e la Milano nei secoli 22 aprile Da piazza della Scala a piazza Belgioioso 27 aprile La lunga storia del Portello ed il nuovo parco Programma elaborato dal team degli Storici dell’Associazione, coordinati dal dott. -

OPEN LETTER in Support of CATHERINE De ZEGHER

OPEN LETTER in support of CATHERINE de ZEGHER About 7 months ago, we learned through the press that Catherine de Zegher had been temporarily suspended as Director of the Museum of Fine Arts of Ghent (MSK). It followed a 7 weeks media campaign of allegations made against the museum and its presentation within the permanent collection of the Russian avant-garde art from the Dieleghem Foundation, based in Brussels. The media allegations had risen to a crescendo, with the most extravagant claims being made, claims, which on examination appeared to have no factual basis and no discernible verifiable evidence. Malign motives were imputed to all those involved with the exhibition. In particular the personal attacks against Catherine de Zegher reached a peculiar and unprecedented intensity that resulted in a trial by media. Under pressure of the escalating and widespread attacks the city of Ghent caved in and temporarily suspended Catherine de Zegher. Today, October 9, 2018, most obviously Catherine de Zegher’s position as “temporally suspended museum director” has not been clarified, and no additional scientific research or independent material-technical expertise have been initiated by municipal, regional, or national government authorities in Belgium to settle the authenticity of the Russian avant-garde works exhibited at the MSK. As a consequence, the mendacious allegations against her are kept alive and the situation seems to be lingering without solution in sight. The scope of allegations and measures of isolation of a director and curator internationally recognized for her artistic vision, her championing of art by women and art from diverse cultures, her broad knowledge and expertise, her ceaseless curiosity, the relevance of her museum programming and the quality of her widely influential exhibitions and many books, stupefy us. -

Frank Bowling Cv

FRANK BOWLING CV Born 1934, Bartica, Essequibo, British Guiana Lives and works in London, UK EDUCATION 1959-1962 Royal College of Art, London, UK 1960 (Autumn term) Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1958-1959 (1 term) City and Guilds, London, UK 1957 (1-2 terms) Regent Street Polytechnic, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Image in Revolt, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1963 Frank Bowling, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1966 Frank Bowling, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1971 Frank Bowling, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, USA 1973 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1973-1974 Frank Bowling, Center for Inter-American Relations, New York, New York, USA 1974 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1975 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1976 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Watson/de Nagy and Co, Houston, Texas, USA 1977 Frank Bowling: Selected Paintings 1967-77, Acme Gallery, London, UK Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1979 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1980 Frank Bowling, New Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1981 Frank Bowling Shilderijn, Vecu, Antwerp, Belgium 1982 Frank Bowling: Current Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, -

Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 094 892 PS 007 449 AUTHOR Snyder, Agnes TITLE Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 421p. AVAILABLE FROM Association for Childhood Education International, 3615 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 ($9.50, paper) EDRS PRICE NF -$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Biographical Inventories; *Early Childhood Education; *Educational Change; Educational Development; *Educational History; *Educational Philosophy; *Females; Leadership; Preschool Curriculum; Women Teachers IDENTIFIERS Association for Childhood Education International; *Froebel (Friendrich) ABSTRACT The lives and contributions of nine women educators, all early founders or leaders of the International Kindergarten Union (IKU) or the National Council of Primary Education (NCPE), are profiled in this book. Their biographical sketches are presented in two sections. The Froebelian influences are discussed in Part 1 which includes the chapters on Margarethe Schurz, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Susan E. Blow, Kate Douglas Wiggins and Elizabeth Harrison. Alice Temple, Patty Smith Hill, Ella Victoria Dobbs, and Lucy Gage are- found in the second part which emphasizes "Changes and Challenges." A concise background of education history describing the movements and influences preceding and involving these leaders is presented in a single chapter before each section. A final chapter summarizes the main contribution of each of the women and also elaborates more fully on such topics as IKU cooperation with other organizations, international aspects of IKU, the writings of its leaders, the standardization of curriculuis through testing, training teachers for a progressive program, and the merger of IKU and NCPE into the Association for Childhood Education.(SDH) r\J CS` 4-CO CI. -

Publications Catalogue 2015–16

Publications Catalogue 2015 –16 Vogue 100 New titles A Century of Style Robin Muir While principally a fashion magazine, Vogue has never been just that. It has assumed a central and vital role on the cultural stage, with a history that spans the most inventive decades in fashion and taste, and in the arts and society. Published to mark the magazine’s centenary, and accompanying a major exhibition, this book celebrates the twentieth century and beyond with an authoritative and discriminating eye. In more than 2,000 issues, British Vogue has acted as a cultural barometer, putting fashion in the context of the wider world – how we dress, how we entertain, what we eat, listen to, watch, who leads us, excites us and inspires us. The century’s most talented photographers, Lee Miller, Norman Parkinson, Cecil Beaton, Irving Penn, David Bailey, Snowdon and Mario Testino among them, have contributed to it. In 1916, when the First World War made transatlantic shipments of American Vogue impossible, its proprietor, Condé Nast, authorised a British edition. It was an immediate success, and over the following ten decades cover Provisional of uninterrupted publication continued to mirror its times – the austerity and optimism that followed two world wars, the ‘Swinging London’ scene 310 x 254 mm, 304 pages of the sixties, the radical seventies, the image-conscious eighties – and in Over 300 illustrations its second century remains at the cutting edge of photography and design. ISBN 978 1 85514 561 0 Decade by decade, Vogue 100 celebrates the greatest moments in Price £40 TBC (hardback) fashion, beauty and portrait photography. -

Catherine De Zegher - the Inside Is the Outside: the Relational As the (Feminine) Space of the Radical

Catherine de Zegher - The Inside is the Outside: The Relational as the (Feminine) Space of the Radical Back to Issue 4 The Inside is the Outside: The Relational as the (Feminine) Space of the Radical by Catherine de Zegher © 2002 It may seem precursory to begin my essay with an image that has been haunting me since September 11, but in a concise way it prefigures many issues I will write about. It is an image of a work by the Chilean artist and poet, Cecilia Vicuna, who has been living in New York for many years. The work dates from 1981 and shows a word drawn in three colors of pigment (white, blue, and red—also the colors of the American flag) on the pavement of the West Side Highway with the World Trade Center on the horizon. It reads in Spanish: Parti si passion (Participation), which Vicuna unravels as “to say yes in passion, or to partake of suffering.” Revealing aspects of connectivity and compassion, the word spelled out on the road was as ephemeral as its meaning remained for the art world. Unnoticed and unacknowledged, it disappeared in dust, but becomes intelligible in the present. This precarious work tells us how certain art practices, in their continuous effort to press forward a different perception of the world, have a visionary content that is marginalized because of fixed conventional readings of art, but nevertheless is bound to be recognized. My essay will seek to uncover the latency of this kind of work in the second half of the twentieth century, which is slowly coming into being today and can be understood because of feminist practice, but also perhaps because of an abruptly changed reality.